Remedy Collections, or Collections of Remedies? - Alun Withey

|

What exactly is a remedy collection? How do we define it? How do we recognise one? On the one hand such questions almost seem redundant: surely it is, as the term suggests, simply a book or manuscript with many pages of medical receipts? In fact, however, even conceptualising the basic character of a remedy collection opens up a wide range of definitional problems but, perhaps more importantly, also raises fascinating questions about the ways in which people in the early modern world collected, spread and recorded medical remedies.

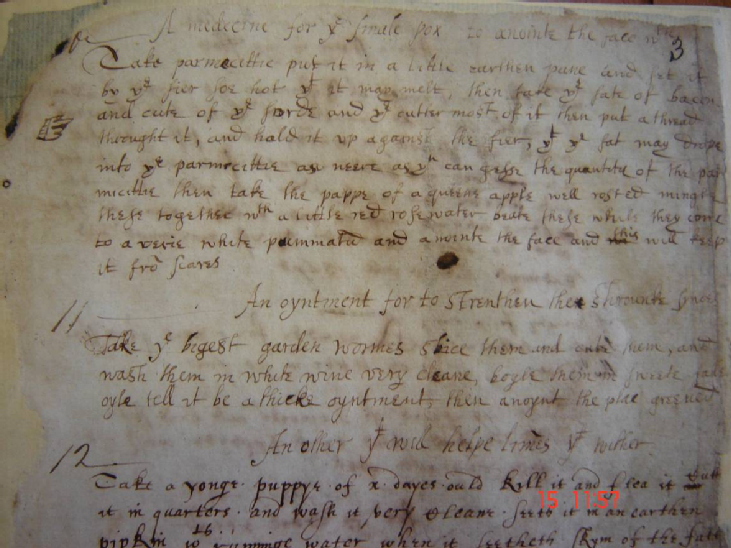

Image 1 - A typical page from a 17th-century remedy book of remedies. Image taken from Glamorgan Archives, MS D/D/Xla, reproduced with kind permission of Glamorgan Archives, Cardiff. During the early modern period, medical remedies formed part of a lively culture of knowledge-sharing. Health was at the forefront of daily conversation, not least because of the vast range of ailments, epidemic and endemic, superficial and chronic, which afflicted people in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This was a shared world of sickness, in which no one was safe and where the pooling and sharing of favoured remedies therefore made much sense. Where, firstly, did remedies come from? At the basis of early modern medical culture was what might be termed a common ‘knowledge bank’ of medical lore. Early modern culture was predominantly verbal: in a period of generally low literacy, the ability to commit knowledge to memory was vital and medical knowledge formed part of a common currency of verbal information which was readily shared from person to person and family to family.

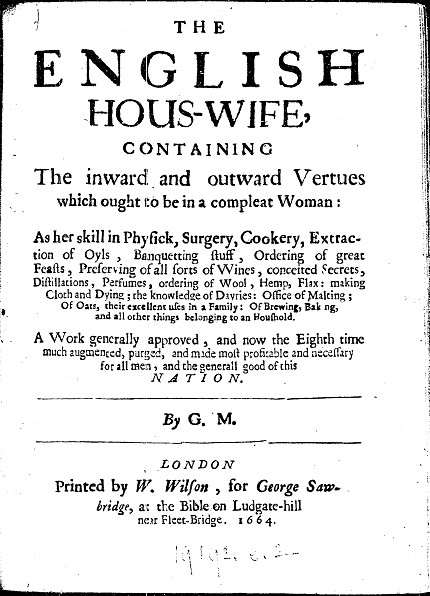

Image 2 – Title Page of Gervase Markham’s seminal publication, instructing housewives in all aspects of domestic life, including preparing medicines. But the ability to commit remedies to paper was certainly an advantage, since it fixed the remedy to a more tangible, and perhaps durable, source, not reliant on the potential failings of memory. Likewise, the assemblage of a large body of medical knowledge into a single volume provided a literate household with a powerful tool. Such a collection might include not only the inherited knowledge of an individual family, but also an accumulation of remedies across a wide spectrum, from personal and social networks to copied passages from owned or borrowed books. Perhaps most formal, and most commonly used of remedy collections by historians, was the Receptaria remedy collection. This was often a carefully and logically constructed document, written in fair hand and generally well indexed. Remedies might be grouped together in several ways, from particular types of ailments, to areas of the body or otherwise simply listed alphabetically. In many cases, although by no means exclusively, the authors of such documents were women, and often elite women. Domestic medicine certainly fell within the realm of household duties expected of women, and conduct books emphasised the duty of women to minister to the sick family. Elite women such as Lady Grace Mildmay, acting in a charitable capacity as ‘lady bountiful’, could also act effectively as practitioners within their local communities, providing medical care and preparations to the sick poor in their parish, giving their remedy collections a utility beyond their immediate domestic context. It is important to remember too that such collections were not fixed to one family or one owner. They had an intrinsic value and might be given as gifts or bequeathed in wills. In time, collections were added to, augmented, evaluated and altered, as subsequent owners added their own trusted cures, or scratched out receipts which had not proved effective.

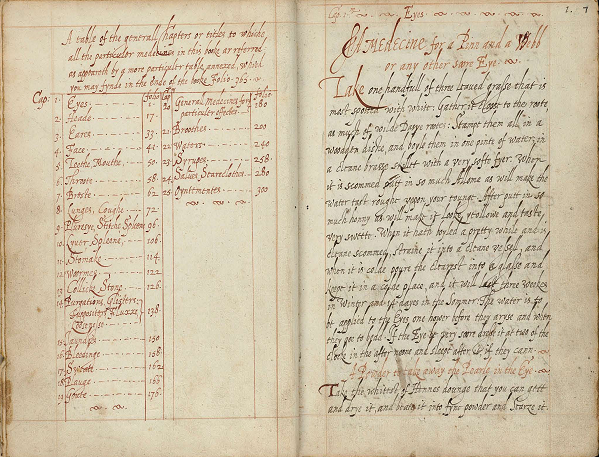

Image 3 – ‘A Booke of diuers Medecines, Broothes, Salues, Waters, Syroppes and Oyntementes of which many or the most part haue been experienced and tryed by the speciall practize of Mrs Corlyon. Anno Domini 1606.", Wellcome Library, MS.213 But the committal of remedies to paper was by no means always so formal or regimented. By their nature, medical receipts were utilitarian – they were important pieces of knowledge meant to be kept for future use. As such, remedies commonly also found their way onto the pages of non-medical sources, such as diaries, notebooks and commonplaces. Such sources were often the domain of gentlemen, whose interest in medicine fitted in with socially acceptable intellectual pursuits. Passages from published medical books might find their way onto the pages of a gentleman’s notebook, while such sources also provided a useful and ready source of paper for noting down a recently acquired remedy. However, the sometimes ad hoc and verbal means of obtaining medical remedies through conversation meant that such remedies might find their way into virtually any document found to hand, from business ledgers to parish registers. But literacy provided a useful ready source of medical remedies in other ways. During the early modern period, the seeking of medical opinions by letter was a useful means of bypassing the potential expense (and discomfort) of a doctor’s consultation. It also, however, had the added benefit of a written receipt from the doctor, which could be kept for future reference. Letters to family and friends detailing symptoms were likely to be rewarded with a response containing a favoured receipt and, again, these could be kept and added to if necessary.

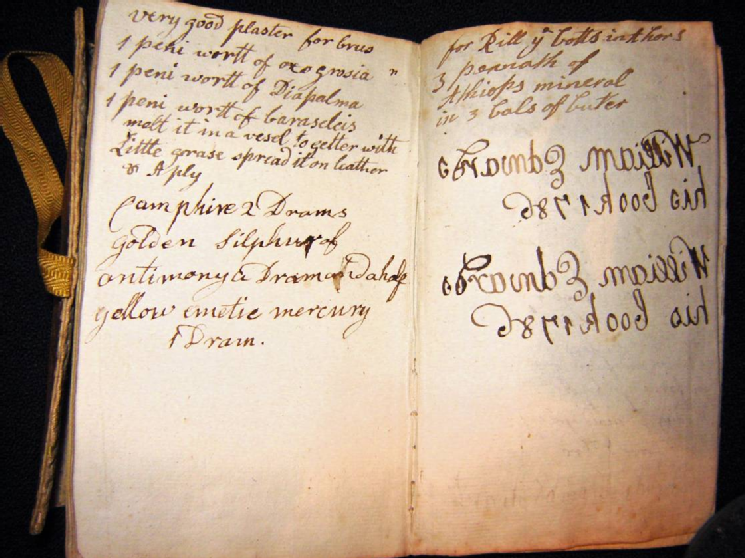

Image 4 - This remedy for a 'bruse' appears in a small 18th century notebook amongst farming information, accounts and poetry. (Author’s private collection: Image copyright) Importantly, though, the ways in which remedies were recorded can tell us much not only about which types of medicines which our early modern forbears used and collected, but also wider issues such as popular fears of sickness, and the value of remedies as a means to mitigate potential danger. A remedy collection, therefore, can be so much more than simply a collection of remedies. |

|