Overcoming Barriers to Interprofessional Communication: How Can Situational Judgement Dilemmas Help?

Frances Varian[1], Dr Anne-Marie Feeley[2] and Dr James Coe[3], Freeman Hospital, High Heaton, Newcastle-Upon-Tyne, Warwick Medical School and Warwick Hospital

Abstract

Background

Interprofessional communication is at the forefront of medical education. However, medical students encounter a number of barriers when learning this essential communication skill (McNair, 2005: 458-49). This study explores the novel development of Situational Judgement Tests (SJTs) into an educational tool - Situational Judgement Dilemmas (SJDs) - to help students develop their interprofessional communication.

Aims

This study aims to evaluate whether SJDs as a formative educational tool can help medical students to develop the skills needed to overcome barriers to effective interprofessional communication.

Methods

SJDs were used formatively and were both self-directed and facilitated by clinicians. This study analysed SJDs undertaken by final-year medical students. Questionnaires (n=100) and two focus group sessions (n=14) assessed SJDs as an aid to understanding and improving healthcare professional relationships.

Results

The questionnaires demonstrated a positive attitude change towards interprofessional communication. The focus groups also revealed positive behavioural and attitudinal changes, including seeking new knowledge about professional roles; enhanced ability of students to reflect on their role in the hospital environment; and increased confidence when communicating with other health professionals.

Conclusion

SJDs can be used successfully during medical training, to encourage reflection on the value of effective interprofessional communication and to enhance such communication in the healthcare setting.

Keywords: Situational judgement tests, SJT, dilemma, interprofessional communication, medical education, Foundation Year 1

Introduction

Effective interprofessional communication is a vital skill which can enhance team function and facilitate high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care (HSERC, 2010: 1-3). Interprofessional communication is becoming increasingly important in our health service today, given an expanding elderly population in an ever more specialised healthcare service (Craddock et al., 2006: 220). Accordingly, competencies have been outlined to better define interprofessional communication. The Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) described such tangible outcomes (CIHC, 2007: 9), outlined in Table 1. However, barriers can arise when teaching interprofessional communication to medical students. These were summarised by McNair (2005: 458-59) as a uni-disciplinary education which narrows knowledge and enhances 'exclusivity'; attitudes which fuel rivalry between disciplines; and role-modelling of negative attitudes and behaviour towards other disciplines. These barriers highlight areas for improvement within interprofessional medical education and call for innovative approaches to effectively teach this vital communication skill.

Interprofessional Communication and the SJT

Situational Judgement Tests (SJTs) - a form of multiple-choice psychological aptitude test - have long been used as a tool for assessment in the private sector (de Meijer and Born, 2009). The UK doctors' training programme recently identified SJTs as a way to test students' knowledge and judgement of a variety of non-technical skills that foundation year one (FY1) doctors should possess (Patterson et al., 2010: 149-58). Applicants are presented with a variety of hypothetical situations likely to be encountered as an FY1. After a successful pilot, SJTs were introduced nationally for 2013 foundation school applicants to test such skills, of which interprofessional communication is an integral part (see Table 1). One advantage of SJTs over other types of personality or cognitive testing is that scores are researched to be a realistic predictor of job performance, inferring transferability of theoretical content into clinical practice (McDaniel et al., 2001: 731-32; de Meijer and Born, 2009; Weekly and Ployhart, 2005: 1-10).

In developing SJTs, the Improving Selection to Foundation Programme (ISFP) harnessed General Medical Council (GMC) guidance and identified nine domains or 'core competencies' of non-technical skills which FY1s must possess (Patterson et al., 2010: 149-58). Although difficult to consider separately, Table 1 demonstrates how the CIHC (2007: 9) interprofessional communication outcomes are readily encompassed within a number of the core competencies required by FY1s.

| CIHC (2007: 9) interprofessional outcomes | GMC FY1 'core competencies' (Patterson et al., 2010: 149-58) |

|---|---|

| 1. Be able to describe one's own role clearly to others | 1. Effective communication |

| 2. Know and respect the role of others in relation to one's own role 3. Know the limitation/constraints of one's own role | 2. Self-awareness and insight |

| 4.Be effective at resolving conflicts | 3. Problem solving and decision-making 4. Coping with pressure |

| 5.Collaborate with others for the needs of the patient | 5. Working effectively as part of a team 6. Patient focus |

| 6.Be tolerant of differences | 7. Commitment to professionalism |

| 8. Organisation and planning 9. Learning and professional development |

Table 1: Interprofessional communication outcomes relative to the SJT assessment.

The nature of overlap between competencies means one SJT will tend to assess a number of interprofessional skills. While this is considered a disadvantage of SJTs as a 'test' (de Meijer and Born, 2009) it can be seen as a strength in utilising SJTs as an educational tool as they lend themselves to developing a more true-to-clinical practice multidimensional skill set. Furthermore, there is a real potential for students to transfer the skills learned from SJTs into the workplace. SJTs should be therefore considered as a valuable tool in which to teach interprofessional communication to medical students and more widely, for healthcare professionals.

Aims

Considering the barriers identified by McNair (2005: 458-59), and the identification of SJTs as an educational tool for developing interprofessional communication, this study aims to evaluate SJTs relative to their utility and acceptability as an interprofessional educational tool for medical students, and their ability to overcome barriers to interprofessional communication.

Methodology

Throughout, for clarity, we have used the term 'situational judgement dilemmas' or SJDs for the educational formative application of SJTs, to distinguish them from the summative situational judgement tests used in national selection.

Developing SJDs as an Educational Tool

SJDs were designed to develop and enhance medical students' confidence and competence in communicating with other healthcare professionals. They were developed by Warwick Medical School from real-life scenarios experienced by clinicians and from clinical case examples from the GMC's 'Good Medical Practice in Action' (GMC, 2013). The format was modelled on the SJT scenarios made available online by the ISFP (ISFP, 2012). Answers to the dilemmas were discussed by consultants, middle-grade and junior doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists and medical students and a 'best fit' answer selected for each scenario.

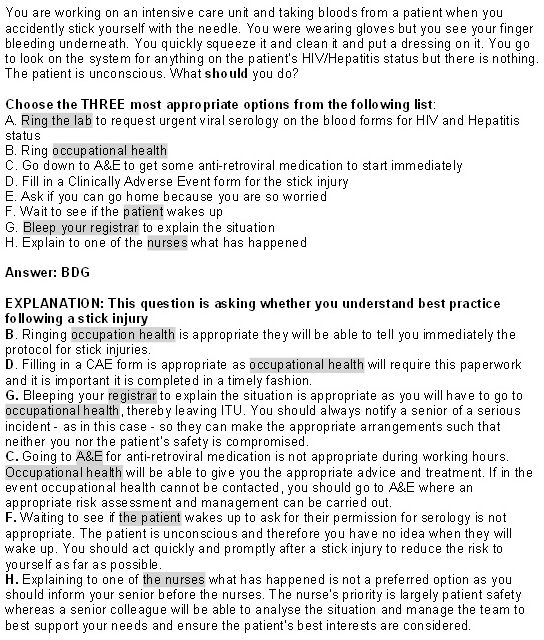

Figure 1: A sample SJD adapted and reproduced with kind permission from Varian, F. and L. Cartwright (2012)

This 'best fit' means SJDs reveal model examples of how students 'should' respond to difficult situations faced as an FY1. Figure 1 exemplifies a typical SJD scenario: the student is asked to analyse his/her response to the dilemma by selecting the three most important actions from a list. Each response lists actions to 'go it alone' or seek help from a team member. By default, these scenarios require students to consider their own role within a team as well as others in the context of the workplace environment. Moreover, the role of each healthcare professional in relation to the dilemma is further explained in the answer to the scenario. This overall design promotes interprofessionalism via the consideration of other healthcare professionals, patients and service users for any given situation.

Implementation of SJDs

Ethical approval was granted by the Warwick Medical School ethics committee in September 2012 for the piloted use of SJDs. Selection included final-year post-graduate medical students with 20 months' clinical exposure. They were recruited prior to sitting the formal SJT exam and had no prior experience of SJT material. The students experienced SJDs as follows:

- All final-year medical students (n=179) were invited to take part in the piloting of SJD teaching materials. 95% of students (n=170) opted to take part. Of these, 100 students were selected at random to complete a 10-point Likert scale questionnaire on their knowledge and confidence regarding interprofessional communication prior to exposure to SJD teaching material (see Table 4).

- Teaching of SJDs involved three phases.

- First, all students attempted a minimum of 16 online SJDs one week prior to an SJD teaching session.

- Each student was also given a workbook detailing the non-technical skills expected of an FY1 (Table 1) and with space to record responses to the following discussions with healthcare professionals:

- Give a brief description of your role in the healthcare team

- Who do you turn to for help?

- Give examples where:

- Confidentiality has been compromised;

- You have had to challenge inappropriate behaviour;

- You have felt pressured;

- You have made a mistake;

- You have had to manage a difficult colleague.

- Each student then attended a one-hour interactive teaching session, delivered by FY1 doctors who received training and feedback on their teaching. The one-hour session included:

- Examples of the FY1s' experiences and the challenges faced within each of the 9 GMC 'core competencies' for FY1 doctors (Table 1) and which team members they went to for help.

- A discussion of students' examples from clinical experience and the workbook relative to these domains.

- 2 SJD scenarios discussed in groups of 10-12 students. Answers were revealed post-discussion.

- An opportunity to ask questions about the roles and responsibilities of life as an FY1.

- A further questionnaire to the 100 students in the study after the teaching session explored whether students' attitudes and knowledge had changed as a result of the SJDs. The original questionnaire asked students to rate their knowledge and confidence with respect to aspects of interprofessional communication along a 10-point Likert scale. The post-questionnaire asked students to rate their knowledge and confidence in each aspect as either 'worse', 'the same', 'better' or 'much better' than before exposure to the teaching session and practice materials.

- One month following the teaching session, a further small number of students were selected at random to participate in a focus group to explore further the usefulness of SJDs. Two focus groups were held, each comprising seven students. The primary aim of the focus groups was to establish whether the self-directed SJDs and supplementary teaching had altered students' approach to the clinical setting in terms of knowledge-seeking behaviour and their attitudes towards interprofessional situations.

Although difficult to consider in isolation, Table 2 demonstrates how the competencies relating to interprofessional communication were explored in this study.

| Core competencies (CIHC, 2007: 9) | Assessment objectives regarding SJDs as a tool for interprofessional education. |

|---|---|

| Collaborate with others for the needs of the patient. | Questionnaire evaluated how students considered their role within patient advocacy. Questionnaire evaluated to what extent students considered carers' perspectives |

| Being able to describe one's own role clearly to others. | Questionnaire and focus group assessed students' understanding of the expectations of an FY1 doctor. |

| Know the limitations and constraints of one's own role. | Questionnaires and focus group assessed recognition of when to seek help from other healthcare professionals. |

| Know and respect the role of others in relation to one's own role. | Focus group evaluated knowledge-seeking behaviour regarding different healthcare professionals. |

| Be effective at resolving conflicts. | Questionnaire and focus group assessed students' understanding of how to maintain harmony within a team. |

Table 2: How SJDs were evaluated against the core competencies of interprofessional communication. Table 3 demonstrates how SJDs were evaluated in their ability to help students overcome barriers to interprofessional communication (McNair, 2005).

| Interprofessional Barriers (McNair 2005: 148-49) | Evaluation |

|---|---|

| Uni-disciplinary education which narrows knowledge and enhances 'exclusivity'. | Questionnaires determined whether SJDs broadened students' knowledge of the role of a FY1 doctor in relation to other healthcare professionals. Focus group addressed whether students more readily identified opportunities to learn from other healthcare professionals on the wards and could reflect on what they learned from these interprofessional interactions. |

| Attitudes which fuel interdisciplinary rivalry. | Questionnaires determined if students' openness to learning about different healthcare professionals' roles was altered as a result of using SJDs. Increased openness to learning was suggested by increased willingness to use the workbook designed to help students create their own scenarios and interview healthcare professionals about their role. Focus group addressed whether this intention resulted in behavioural change demonstrated by use of the student workbook. |

| Role-modelling of behaviour towards other disciplines. | Questionnaire evaluated whether student's attitudes towards other healthcare professionals changed as a result of using SJDs. Focus group addressed whether SJDs altered behaviour towards other disciplines by seeking new knowledge on the wards. |

Table 3: Evaluating whether SJDs can overcome interprofessional communication barriers.

Results

There was a 100% response rate to the questionnaires. Student reaction to teaching using SJDs was positive: 89% of students rated ≥7/10 for SJDs providing 'value beyond learning on the wards'. 94% of students also rated SJDs ≥7/10 as 'enjoyable' and 'valuable for their learning'. Table 4 illustrates the results of the 100 questionnaires before and after the SJD teaching.

| Principle of Interprofessional Communication | Pre-Questionnaires (mean score out of 10) | Post-Questionnaires % rating 'better' or 'much better' |

|---|---|---|

| Extent to which students consider their role as an advocate for patients. | 8.7 | 61% |

| Extent to which students consider carers' perspectives. | 6.9 | 61% |

| Extent to which students understand the different roles of healthcare professionals. | 6.6 | 80% |

| Extent to which students feel confident knowing when to seek help from other healthcare professionals. | 5.7 | 88% |

| Extent to which students seek out knowledge of other healthcare professionals' roles. | 6.0 | 73% |

| Extent to which students understand the non-technical skills required as an FY1. | 6.9 | 79% |

| Extent to which students understand how important teamwork is in their future role as a FY1 doctor. | 9.2 | 60% |

| Extent to which students understand the expectations of an FY1. | 6.2 | 92% |

Table 4: Change in knowledge, attitudes and confidence of students in relation to different aspects of interprofessional communication before and after SJD teaching.

From the pre-teaching questionnaire it is evident that students already placed great emphasis on certain key elements of interprofessional communication, in particular patient advocacy and the importance of team-work (Table 4). However, they felt less confident about the following: knowing what is expected of them as an FY1, knowing when to seek help from others, and knowing which healthcare professionals to seek help from for a given situation. As highlighted in Table 4, following the completion of SJDs, ≥80% of students had a 'better or much better' understanding of these three areas. Moreover, across all areas, no students felt 'worse' in any area. Where student knowledge was already high, e.g. teamwork, smaller gains in knowledge post-SJD were achieved. Given that improvements were identified across all areas, the questionnaire results promote SJDs as an interprofessional tool valued by medical students.

The facilitated discussion of the dilemmas was found to be of the greatest benefit to students:

'Having a debate about the different answers, that was useful - to bounce of ideas off other people.'

'The discussion of the workbook was most useful for me - listening to other people with similar situations where things played out differently; it was good to evaluate and think 'what is the right thing to do?'

'The session with the FY1 in small groups was really useful. Instead of having to hunt out situations, FY1s have been working and experienced them. They tell you what happened, discuss what they thought should have happened and then told you what did happen. It was really really useful to have someone who has a vast experience compared to what we have on the wards share that as we don't get to see as much.'

Formative SJDs created a platform for discussing non-technical skills, interpreting and appreciating others' responses to workplace scenarios and learning more about the FY1 job role. These are key aspects of interprofessionalism and demonstrate the applicability of SJDs as an educational tool within this area.

Evaluating the barriers to interprofessional education, the results of the questionnaire demonstrated that SJDs also broadened students' knowledge of the role of an FY1 in relation to other healthcare professionals. This was evident particularly from the focus group discussion. Students engaging with SJDs shifted their focus from only thinking of a 'medical student perspective' to considering their role within the wider context of other healthcare professionals. The students were able to reflect on the need to understand their own role clearly, as well as the roles of others.

'Practising SJDs made me realise I lacked knowledge of what is expected of FY1s. Since then I've been taking more notice of what they actually do, asking questions and advice.'

'Talking to the team has been helpful as before I was quite focused on being a doctor and everything a doctor is doing but you need to know about other people and their roles too.'

These quotes demonstrate the attitudinal change from exclusively considering their role to appreciating it within the wider context of the multidisciplinary team. A second adjustment identified was openness to learning. Prior to completing the SJDs 2% of students reported using the workbook that Warwick Medical School designed to facilitate interprofessional communication. Following completion of the SJDs 98% of students agreed to use the workbook. This intention was followed by behavioural change among the students: all 14 focus group members had used the workbook following the questionnaires. In addition, students felt empowered by the SJD to approach other healthcare professionals for advice and help: 'I had an excuse to ask questions.' This inquisitiveness was extended towards all members of the healthcare team:

'I have become more aware of different roles of healthcare professionals, asking more questions to registrars, nurses, pharmacists, everyone I meet about their role in the structure of the team … it has definitely caused me to ask more questions on the wards.'

As demonstrated above, students attending the focus group reported clear examples of knowledge-seeking behaviour regarding communication with other members of the healthcare team. This positive culture of openness to learning was highlighted by McNair (2005: 458) as one that is less likely to fuel interdisciplinary rivalry.

The final barrier identified by McNair (2005: 459) concerned negative role-modelling and negative behavioural attitudes towards other disciplines. From the pre-SJD teaching questionnaire (Table 4), it was evident that students lacked understanding of other healthcare professionals' roles. This could lead to mistaken or negative attitudes based on a lack of knowledge. The improved confidence in these areas following the SJD teaching (Table 4) suggests that knowledge regarding others' roles can be enhanced by SJDs. This theme was also clearly demonstrated in the focus group:

'The fact that SJDs are there has got me thinking about being proactive, about asking questions, thinking about different roles and what you should do in different situations.'

This quote demonstrates how SJDs can be considered as a useful tool for attitudinal change as their design promotes a multidisciplinary approach to problem-solving. Moreover, the structure broadens students' desire to learn about other healthcare professional roles by contextualizing the need for such knowledge in an easy to interpret, clinical context.

A final (and unexpected) result of this study was the very positive response of the FY1 doctors who volunteered to teach the SJD sessions. Preliminary feedback reports suggest that they welcomed the opportunity to share their practical experience and learning in this important area of professionalism: 'The sessions were a real opportunity to develop my teaching skills. Despite being a newly qualified junior doctor, I have already seen situations similar to many of the scenarios. This meant I felt ideally placed to deliver the material and engage students in relevant discussion.'

Discussion

This study suggests that the use of SJDs can help medical students identify gaps in their understanding of their own role as junior doctors, and of the roles of other healthcare professionals. Moreover, following completion of the SJDs, students exhibited both attitudinal and behavioural changes, exemplified by an increase in approaching and speaking to other healthcare professionals on the wards, and an increased interest in the roles of others in the healthcare team. The students also valued the time given by FY1s to teach the importance of interprofessional communication. This role-modelling positively influenced the attitudes of medical students in this area.

Although the teaching sessions required busy FY1 doctors to give up their time to prepare and lead the sessions, it was nevertheless easy to recruit FY1s to teach SJDs. Furthermore, their enjoyment of the sessions was high. This suggests that it is feasible to continue these sessions in future years, as both the students and doctors involved valued and gained educationally from the sessions.

Although this pilot study involved FY1 doctors teaching SJDs to medical students, there is considerable scope to include other healthcare professionals and utilise SJDs in a multidisciplinary environment. The scenarios were created with assistance from multiple healthcare professionals and as such, are dilemmas with which many healthcare professionals should identify. Developments within this field are increasingly moving towards face-to-face shared learning between different healthcare professionals (Finch, 2000: 1138-40); however, to date there have been numerous logistical barriers identified, including co-operating with other universities to access different specialties, timetabling different course structures and content, and co-ordinating different term times (Finch, 2000: 1138-40; Parsell and Bligh,1998: 94). SJDs offer shared learning indirectly, by inspiring students to discuss the roles of others in such situations and seek out knowledge of such roles. Moreover, with resources permitting, SJDs are a simple tool that could easily be used in a face-to-face learning environment to enhance interprofessional communication. Furthermore, SJDs could be utilised within the hospital setting to facilitate interprofessional communication between qualified healthcare professionals, providing a neutral context for non-threatening, theoretical, case-based discussions.

Sampling Bias and Limitations

In total, 95% of the medical student cohort attended the voluntary SJD teaching sessions. Due to time constraints, 100 of the 170 students were selected at random for inclusion in the study. This sample size was considered large enough for the purposes of this evaluation, and the random sampling of the cohort sought to minimise selection bias. However it cannot be known whether alternative opinions may have been missed by restricting our sample size in this way.

This study was based at Warwick Medical School, which is a postgraduate medical school (i.e. all students have a prior honours degree before entering medical training). It is not known whether the behavioural responses of our students to SJDs would differ from an undergraduate medical school cohort. However, as all medical students in the United Kingdom are expected to follow the same curriculum and to demonstrate similar qualities relative to learning by the time they qualify (GMC, 2009) it is thus at least plausible that the positive results found in this study could generalise to undergraduate medical students.

SJDs are not without their limitations. Although arguably less resource-intensive than other interprofessional education methods, they still carry some material cost. SJDs are expensive to produce, as high-level clinical knowledge is needed to develop meaningful dilemmas. In addition, feedback and group discussion led by an experienced teacher are needed to maximise the learning experience from SJDs.

With respect to this study design, limitations exist when confirming behavioural changes using focus groups. There is a danger of inferring large-scale change from a small sample size and additionally there is no guarantee that interprofessional ways of working as a medical student will continue into foundation-year training.

Finally, it is important to consider the potential disadvantages of using SJDs in a formative way, as we have done. Although this kind of teaching allows students to explore and discuss the dilemmas openly without fear of being 'graded', it is important that there are also mechanisms in place to identify those who are struggling with the dilemmas, or those who may have professional difficulties which need to be explored further if they are to proceed safely into clinical practice. When implementing SJDs as a formative teaching tool, we propose that any self-directed material should be supported by discussion with healthcare professionals. This will enable appropriate student support to most effectively facilitate learning.

Conclusion

From this study, SJDs emerge as a potentially valuable and effective supplement to other interprofessional teaching tools. The principles of interprofessional education can be clearly demonstrated within the content of the dilemmas. Moreover, SJDs are accepted by students as a useful mechanism for learning about professionalism, and students find them valuable for developing such skills on the wards. Our cohort of final-year students demonstrated deficits in knowledge that could act as a barrier to effective interprofessional communication, most particularly in the realm of knowing the roles and responsibilities of other healthcare professionals and their own future role as FY1s. This study shows that this knowledge barrier can be overcome with the use of SJDs as an educational tool. Finally, students demonstrated behavioural changes following the SJDs and reported improved interprofessional communication between healthcare professionals and medical students in the clinical setting. Although the impact of these changes needs more exploration longer-term, the evidence suggests that SJDs could prove a fruitful and dynamic interprofessional learning resource.

Future avenues for research

Future research on the longer-term impact of SJDs is likely to be fruitful. Furthermore, there is scope to analyse the use of SJDs for wider dissemination throughout the different healthcare professions.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Lara Cartwright, Deborah Markham, Judith Purkis, Anne-Marie Slowther and Neil Johnson, for their support during the six-week elective at Warwick Medical School conducted by F. Varian. This elective involved developing SJD teaching materials for Warwick medical students, and the publication of a practical workbook on the subject for general readers.

List of figures

Figure 1: A sample SJD adapted from Varian, F. and L. Cartwright (2012)

List of Tables

Table 1: Interprofessional competencies relative to the SJT assessment.

Table 2: How SJDs were evaluated against the core competencies of interprofessional communication.

Table 3: Evaluating whether SJDs can overcome interprofessional communication barriers.

Table 4: Change in knowledge, attitudes and confidence of students in relation to different aspects of interprofessional communication before and after SJD teaching.

Notes

[1] Frances Varian graduated Warwick Medical School in July 2013 and attained a 2 year academic clinical foundation post at Newcastle Upon Tyne Hospitals. She is currently working as a foundation year one doctor within vascular surgery and her special interests include communication and medical education. She is in the process of setting up a teaching programme at the Freeman Hospital for foundation doctors.

[2] Dr. Anne-Marie Feeley is senior clinical teaching fellow and academic lead for personal and professional development at Warwick Medical School. She is a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, with a special interest in medical education.

[3] Dr. James Coe is a Foundation Year 2 doctor currently working in general practice in Coventry. He received his MBChB (hons) from the University of Warwick in 2012, having obtained a BSc (hons) in Neuroscience from the University of Bristol in 2008. He is a member of the British Society of Medical Dermatology and plans to train as a dermatologist.

References

Canadian Interprofessional Health Collaborative (CIHC) (2007), 'Interprofessional Education and Core Competencies: literature review', Canada: CIHC, 1-18

Craddock, D., C. O'Halloran, A. Borthwick and K. McPherson (2006), 'Interprofessional education in health and social care: fashion or informed practice?' Learning in Health and Social Care,5 (4), 220-42

de Meijer, L. A. L. and M. P. Born (2009), 'The situational judgement test: Advantages and disadvantages', in Born, M., C. D. Foxcroft and R. Butter (eds), Online Readings in Testing and Assessment, International Test Commission [pdf], available at http://www.intestcom.org/Publications/Orta/The%20situational%20judgment%20test.php accessed 5 October 2013

Finch, J. (2000), 'Interprofessional education and teamworking: a view from the education providers', British Medical Journal, 321 (7269), 1138-40

General Medical Council (2009), Medical students: professional values and fitness to practise, GMC and Medical Schools Council: UK

General Medical Council (2013), 'Good Medical Practice In Action', available at http://www.gmc-uk.org/gmpinaction/, accessed 5 August 2013

Health Sciences Education and Research Commons (2010), Interprofessional Learning Pathway Competency Framework, Alberta, Canada: University of Alberta, pp.1-6, available at http://www.hserc.ualberta.ca/en/TeachingandLearning/VIPER/EducatorResources/~/media/hserc/Documents/VIPER/Competency_Framework.pdf accessed 6 October 2013

ISFP (2012), 'Situational Judgement Test', available at http://www.isfp.org.uk/Pages/SJT-and-EPM.aspx, accessed 5 August 2013

McDaniel, M. A., F. P. Morgeson, E. B. Finnegan, M. A. Campion and E. P. Braverman (2001), 'Use of situational judgment tests to predict job performance: a clarification of the literature', Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 730-40

McNair, R. P. (2005), 'The case for educating health care students in professionalism as the core content of interprofessional education', Medical Education, 39 (5), 456-64

Parsell, G. and J. Bligh (1998), 'Interprofessional Learning', Postgraduate Medical Journal, 74, 89-95

Patterson, F., V. Archer, M. Kerrin, V. Carr, L. Faulkes, H. Stoker and D. Good (2010), Improving Selection to Foundation Programme Final Report Appendix D: FY1 Job Analysis, Cambridge: Work Psychology Group, pp. 126-240

Varian, F. and L. Cartwright (2012), The Situational Judgement Test At A Glance, Oxford: Wiley Blackwell

Weekly, J. A. and R. E. Ployhart (2005), Situational judgment tests: theory, measurement and application, New York: Lawrence Erlbaum pp. 1-10

To cite this paper please use the following details: Varian, F. et al (2013), 'Overcoming Barriers to Interprofessional Communication: How Can Situational Judgement Dilemmas Help?,' Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 6, Issue 2, www.warwick.ac.uk/reinventionjournal/issues/volume6issue2/varian accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal at warwick dot ac dot uk.