The Changing Faces of Medusa

Sarah Bernice Wallace[1], Department of Classics, University of Reading

Abstract

Who was the real Medusa? And what was she to the ancient Greeks? The myth of Perseus's conquest over the monstrous Medusa is well known; however, in Greek antiquity her role varied greatly, and rarely was she simply 'monstrous'. This paper addresses the differing representations of Medusa on black- and red-figure pottery, providing a broader look at Medusa and her role in the realm of Greek myth and thought, and demonstrating that she was portrayed in differing ways as monster, victim and comic. In tracing her ideological functions throughout Greek antiquity we will examine who the definitive Medusa was, how she was viewed by the ancient Greeks, and what functions she performed in Greek myth and iconography. By examining both the pottery itself and leading scholarship on the subject, this article tracks the changing faces of Medusa not simply in a chronological, linear sense, but also in an ideological one, tracing the origins of Medusa's juxtaposing characteristics as both funny and frightening.

Keywords: Gorgon, Medusa, pottery, ancient Greece, iconography

Medusa as Monster

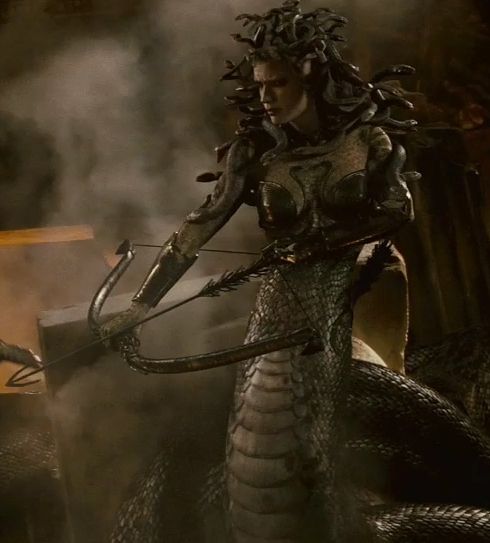

If we were to examine the presentation of Medusa in the modern day, we would be in no doubt as to who she is: she is a monster. With her combination of human and animal features, and her ability to turn people to stone with a single glance, her appearances in numerous films such as Clash of the Titans (Figure 1) serve to exemplify her monstrosity.

Figure 1: Medusa in Clash of the Titans, 2010. [Source: IMDB]

Indeed, it can be safely said that the surviving legacy of Medusa's character is her monstrousness and nothing more. As we begin to look at the ancient Medusa, however, we see her as an entirely complex being, and one who performed many roles in Greek imagination and thought. As begin to delve deeper into the character of Medusa, we come to realise that she had a much closer relationship with representations of emotion and passion, both of which are reflected in her many and complex artistic representations. With this in mind, the appearance of the beautiful Medusa in around the 5th century BC should come as no surprise. Her arrival does, however, generate a number of questions: was her new-found beauty genuine? Did the Greeks genuinely begin to pity her? Could she even be considered as a victim?

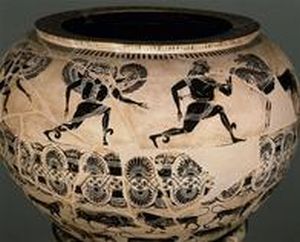

In order to appreciate fully the differing presentations, it is necessary to look back at a much more monstrous example of Medusa's role in Greek thought. Figure 2 depicts a standard archaic Medusa scene such as was very popular throughout the archaic period.

Figure 2: Attic black-figure dinos (mixing bowl), painted by the Gorgon painter, 600-590BC, Louvre, Paris. [Photo courtesy of H. Lewandowski, www.louvre.fr]

Here Perseus has already beheaded the dreaded Medusa, and is making his escape while being pursued by her Gorgon sisters. The scene is a simple one: Perseus looks forward, and is depicted in profile, fixed on his escape. The Gorgon sisters are frontal faced and profile bodied, allowing the artist to provide a detailed depiction of their faces, while suggesting movement and pace in their pursuit. Their faces are a mismatch of human and animal features, with protruding tongues and menacing frowns that make their aggression clear to the viewer. Woodford notes that artists were in fact challenged in creating a monster so hideous as to appear 'capable of inducing such grievous terror' (2003: 128). Indeed in this depiction, as in many other archaic portrayals, Medusa and her sisters are definitely all monster: the inclusion of the gruesome beheaded body of Medusa, the pursuing sisters, who jeopardise the hero's life with a mere look, as well as the hero's panicked flight: all serve to demonstrate to the viewer the fear and panic that these creatures could incite. Thus the situation is made clear, namely that Gorgons are something even great Greek heroes fear, and as if that alone is not enough then the frontal display of their monstrous faces certainly tells the reader of their standardised characterisation in Greek thought as monsters.

Medusa as Beauty

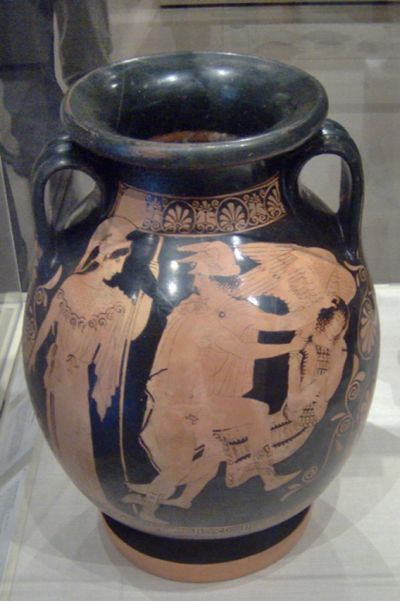

Upon examination of Polygnotos' pelike (Figure 3) from around 450BC, it becomes evident that a notable change has taken place in the depiction of Medusa since the dinos (Figure 2) was produced around 150 years earlier; indeed, the whole scenario has been inverted.

Figure 3: Attic red-figure pelike (a two-handled vessel used for storage), painted by Polygnotos, 450-440BC, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Photo courtesy of Peterjr1961 of www.flikr.com]

Medusa, the Gorgon, lies peacefully asleep, unaware of Perseus's presence and her imminent danger. Perseus has now taken on the role of the aggressor, sneaking up behind Medusa, scythe poised. The preferred scene in the 5th century BC is now the moment before Medusa's decapitation, an image which expressed the 'calm before the storm'. This facilitates the casting of Medusa and indeed even her sisters as victims, as such scenes have no need of the dreaded pursuing Gorgon sisters. Thus in this void of Gorgon aggression, Medusa easily becomes an innocent victim. The most noticeable change, however, lies not in the overall narrative of the scene, but in the presentation of Medusa herself. On Polygnotos' s pelike we see a relatively normal woman, whose only extraordinary features are her pair of wings. The appearance of these 'beautiful Medusas' during the 5th century BC clearly represents a change in Greek thought concerning the Gorgons, but even if Medusa has now become a victim, then surely it is not necessary for her to be beautiful? Vernant notes that in both Appolodoros's and Pindar's much later (4th century AD) renditions of the myth it is in fact Medusa's excess beauty which acts as a catalyst for the drama, either because Athena then acts out of jealousy or because Perseus, so dazzled by her beauty, cuts off her head to ensure he is never separated from it (Vernant, 1991: 149). It seems that her beauty is used to cultivate pathos in the viewer as well as to instigate the drama of the myth. Her monstrous features have had to be removed in order to allow the viewer to identify, and indeed sympathise, with Medusa. This notion is used to such an extent that it is even evident in literary texts such as Pindar's Pythian Odes. Pindar places the wailing lamentations of the Gorgon sisters as Athena's inspiration for the invention of the Aulos and the 'many-headed tune':

Which Pallas Athena once invented

By weaving into music the fierce Gorgons deathly dirge

That she heard pouring forth from under the

Unapproachable,

Snaky heads of the maidens in their grievous toil,

When Perseus cried out in triumph as he carried the third of the sisters.

(Pythian Odes, Ch.12: ll.7-11)

It is noticeable here that the focus is much more on the mourning of Medusa's sisters, than on the triumph of Perseus. Thus we can conclude that Pindar's audience was to some extent expected to sympathise and engage with the Gorgon sisters. Furthermore the existence of this perception in literary texts demonstrates the solidity of this idea in Greek thought, not only in artistic expression, but also in literature. Thus we can conclude that the ancient Greeks perhaps liked this interpretation enough to immortalise it not just in myth and on pots but in literature as well.

However, the beginnings of this transition from Medusa as monster to Medusa as beauty cannot be simplified to just one text or pot. Such a change in Greek thought as a whole took time: as Henle notes, these changes took place over the whole of the 5th century (Henle, 1973: 90) and despite these changes many of the iconographical features remained the same. Perseus, for example, is still represented as a hero, dressed up in all the possessions given to him by the gods. Medusa retains some of her monstrous features (wings, protruding tongue, and even in some cases, snakes in her hair) but unlike the Gorgon painter's black-figure dinos (Figure 2) on which Perseus's heroic attire reassures the viewer that the gods were on his side, on Polygnotos's pelike (Figure 3) these attributes become somewhat redundant: what need has Perseus of winged boots if the creature he wishes to slay is already asleep and subdued? Indeed the winged boots allow us as the viewer to identify him easily; furthermore, at any moment Medusa could wake up and Perseus's plan could fall to pieces, giving a hint of tension to the whole scene. Perseus's solemn facial features, as he turns his face away from Medusa and towards the goddess Athena, suggest not only his understanding of what he is about to undertake, but reiterate to the viewer the solemnity of the whole scene.

Medusa as Victim

How far Medusa's newfound beauty manifests the viewer's pathos is debatable; not all beautiful Medusas can be considered ' normal', let alone beautiful. An Attic bell krater (Figure 4) by the Villa Giulia painter made around the same time as the pelike in Figure 3 depicts more or less the same scene.

Figure 4: Attic red-figure bell krater (a rounded vessel used for mixing wine and water), by the Villa Giulia painter, 460-450BC, British Museum, London. [Photo courtesy of the British Museum]

Medusa sleeps while a solemn Perseus creeps up on her, ready to deliver the fatal blow. Unlike Polygnotos's rendition, this Medusa still displays some of her monstrousness: her squashed nose and protruding tongue give away her Gorgon roots, and, like the Gorgons of archaic times, she is frontal facing. Indeed, at a glance, this Medusa could be mistaken for monstrous. Despite her ugly features, she is still very human in appearance (Topper, 2007: 81): we see her sleeping, propped up against some object we are unable (due to the damaged state of the vase) to identify, with her arm draped over her lap. These are all features that are likely in the average human sleeper, and overall her body is as anthropomorphised as the Medusa in Figure 3. The only difference between the two is evident in their facial features. It could be argued therefore that the Villa Giulia painter has perhaps chosen to be deliberately ambiguous and has created a mismatch between the solemnity of some contemporary examples and the humorous nature of others (see Figure 5). The artist has kept the composition of the pelike in Figure 3, however, and it is with this in mind that I suggest that this may have been a slightly failed attempt at a sombre scene of Medusa's death. None of the other figures (Hermes, Athena and Perseus, in this case) seem to have the sense of movement and fluidity as is seen in the Pan Painter's much more skilled depiction on his red-figure hydria (Figure 5). Nor is Athena in Polygnotos's pelike seen to be as flighty for she stands solemnly at the side of the scene. Thus it is from the reaction of the other characters, not that of Medusa herself, that I conclude that this scene was intended to portray a sympathetic account of Medusa's death and not a mocking one.

Medusa as Comic?

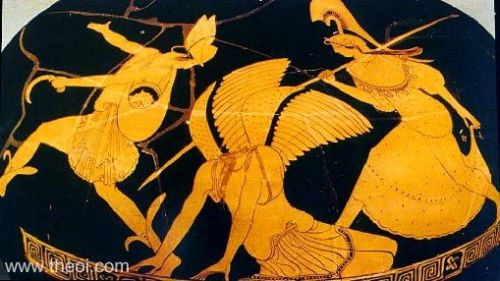

It would not be correct to say that absolutely no comedic representations of Medusa existed at this time: the Pan painter's red-figure hydria (Figure 5), mentioned above, was also created around this time.

Figure 5: Attic red-figure hydria (a two-handled vessel used for storing water), painted by the Pan painter, second quarter of the 5th century BC, British Museum, London. [Photo courtesy of www.theoi.com]

This piece addresses the beheading of Medusa, although with the scene after the actual beheading portrayed. It is by no means a threatening, scary scene, but rather seems to extend the playfulness that the Villa Guilia painter hinted at in his rendition of Medusa's death (Figure 4). Perseus instead light-heartedly leaps away, arm outstretched while his head turns back to see the decapitated Medusa. Athena follows after him, in an equally light-hearted manner. Medusa's head rests somewhat happily in Perseus's kibisis, her eyes closed in a manner that would indicate her happiness to the viewer. Indeed it is Medusa's reaction that sets the whole piece off as an example of what Sparkes calls a 'dainty ballet dance' (Sparkes, 1996: 96). It is truly remarkable the way the artist has used the curve of the hydria to make this scene come to life, enhancing the scene's overall playfulness by using the full space available to him and depicting the narrative scene in a curve around the hydria. It is clear to the viewer that this is meant to be a humorous scene: Sparkes notes that the painter had 'a sharp sense of the ridiculous' (1996: 96) as exemplified by Athena, who, brandishing a huge spear, daintily picks her way over the fallen body of Medusa, holding up her dress as she follows Perseus out of danger. Although this depiction may have some comedic quality, a few iconographic conventions are kept: the positioning of Medusa's body, although awkward and unnatural, seems to suggest that she was facing forwards when she was beheaded; Perseus is still clothed in his heroic garb; and Athena is still present, albeit in a more submissive role than previous depictions in this context.

There are many other unusual classical representations of the Medusa myth. Perhaps it seems that around this time the idea of a humorous Medusa seemed quite popular, for example a red-figure kantharos (Figure 6) from around 420 BC, which, despite depicting Perseus being pursued by a gorgon, still manages to convey a sense of humour to the audience.

Figure 6: Red-figure kantharos (drinking vessel), 420-400BC. Strasbourg, Institut d'archéologie classique. [Photo courtesy of Harvard College Library]

For example, the artist has chosen to depict Perseus on one side of the pot and the pursuing Gorgon on the other, thus engulfing the whole pot in this short narrative and providing a wonderful visual display for the viewer, to whom it seems the Gorgon will be forever chasing Perseus around the pot, with no hope of catching him. This is a very different chase to the one seen on the Gorgon painter's dinos (Figure 2), and must not be confused with the earlier, much more vengeful Gorgons of archaic times. As Topper rightly notes, this depiction represents a kind of topsy-turvy 'world in which monsters are beautiful and heroes flee maidens' (Topper, 2007: 81). Indeed, the Gorgon we are presented with here is very much a maiden, aside from her wings, as in the Polygnotos painter's pelike (Figure 3), except that in this depiction she is the aggressor. Furthermore, Topper, having examined numerous vases depicting the Gorgons chasing Perseus as well as numerous erotic chases on Greek vases, notes that this doubly inverted representation of the Gorgons' pursuit of Perseus in fact has erotic connotations (Topper, 2007: 82). When compared to an early classical red-figure amphora, which depicts a man chasing after a maiden (Figure 7), the similarities become clear.

Figure 7: Red-figure amphora (two-handled vessel for storing water), early classical, St. Petersburg, State Heritage Museum. [Photo courtesy of the State Heritage Museum, St Petersburg]

Both have only two figures depicted on them, one fleeing, the other pursuing. Both have each character portrayed on different sides of the pot. Indeed similarities even stretch to the characters poses; the pursuers both have outstretched arms while both Perseus and the fleeing maiden glance backwards in their flight. Topper states that these few actions have so much weight behind them in Greek thought that in this case only two figures are needed to indicate the depiction's erotic nature (2007: 82).The Perseus in the Pan painter's depiction (Figure 5) is posed almost exactly the same way as the Perseus fleeing from the Gorgon's erotic pursuit (Figure 7) and given the light-hearted nature of both scenes it is easy to conclude that the erotic dimension of the Gorgons goes somewhat hand in hand with the comedic takes on this myth .

Conclusion

So where does this leave us? Essentially there seem to have been many different types of Gorgon throughout the Greek age, spanning from the archaic period in 700BC all the way to 325BC; unlike the modern-day Medusa who is strictly a monster, the ancient Greeks' concept of Medusa and the Gorgons seems to be much more fluid. She seems to be many things combined: a monster, a victim and a comedian. She is as complex as the Greek imagination wished her to be. But perhaps this complexity is necessary when we take into account the many ways in which Medusa and the Gorgons appear in ancient Greek pottery, we begin to see her complexity as a necessity. This is exemplary in the way in which her artistic representations can grow and be manipulated to suit whatever circumstances the ancient Greeks saw fit.

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: Medusa in Clash of the Titans, 2010. Source: IMDB.

Figure 2: Attic black-figure dinos (mixing bowl), painted by the Gorgon painter, 600-590BC, Louvre, Paris. Photo courtesy of H. Lewandowski, www.louvre.fr.

Figure 3: Attic red-figure pelike (a two-handled vessel used for storage), painted by Polygnotos, 450-440BC, New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo courtesy of Peterjr1961 of www.flikr.com

Figure 4: Attic red-figure bell krater (a rounded vessel used for mixing wine and water), by the Villa Giulia painter, 460-450BC, British Museum, London. Photo courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 5: Attic red-figure hydria (a two-handled vessel used for storing water), painted by the Pan painter, second quarter of the 5th century BC, British Museum, London. Photo courtesy of www.theoi.com.

Figure 6: Red-figure kantharos (drinking vessel), 420-400BC. Strasbourg, Institut d'archéologie classique. Photo courtesy of Harvard College Library.

Figure 7: Red-figure amphora (two-handled vessel for storing water), early classical, St. Petersburg, State Heritage Museum. Photo courtesy of the State Heritage Museum, St Petersburg.

Notes

[1] Sarah graduated from the University of Reading in July 2011 with a degree in Classical studies, and is currently seeking a career in the museum sector.

References

Henle, J. (1973), Greek Myths: a Vase Painters Notebook, London: Indiana University Press

Race, W. H. (1997), Pindar- Olympian Odes, Pythian Odes, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press

Sparkes, B. A. (1996), The Red and The Black, Studies in Greek Pottery, London: Routledge

Topper, K. (2007), 'Perseus, The Maiden Medusa, and The Imagery of Abduction', Hesperia, 76, 73-105

Vernant, J. P. (1991), In the Mirror of Medusa, in Mortals and Immortals, Collected Essays, ed. F. I. Zeitlin, Princeton: Princeton University Press

Woodford, S. (2003), Images of Myths in Classical Antiquity, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

To cite this paper please use the following details: Wallace, S. B. (2011), 'The Changing Faces of Medusa', Reinvention: a Journal of Undergraduate Research, British Conference of Undergraduate Research 2011 Special Issue, http://www.warwick.ac.uk/go/reinventionjournal/issues/bcur2011specialissue/wallace. Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal at warwick dot ac dot uk.