Commemorative Funerary Monuments in Reformation Bristol c. 1490–1640

Eleanor Barnett[1], Department of History, University of Warwick

Abstract

This article evaluates the impact of the English Reformation on the way in which people were commemorated after death in Bristol c. 1490 to 1640. It adds the important case study of Bristol to a prospering historiography on Reformation commemoration. By studying both extant monuments and accounts of those since lost it is evidenced that pre-Reformation monuments belonged within an overarching practice of commemoration in which the dying requested prayers for their souls to pass through purgatory. It is argued that post-Reformation monuments reflect changes in religious beliefs but are no more 'secular' than they were prior to the Reformation. Social developments are also read from Reformation commemoration. Bristol's mercantile hegemony accelerated a nationwide change in elite values, from the importance of lineage to an emphasis on wealth and individual merit. The conclusion reflects upon the changed nature of remembrance as a result of the Reformation, from a request for intercessory prayer, to the internal remembrance of personal attributes.

Keywords: English Reformation, commemoration, funerary monuments, Bristol, death, remembrance.

Introduction

The commemorative monuments that fill the interiors of medieval parishes are by their very nature expressions of the past, and are therefore of obvious use to the religious and social historian. However, they are often found hidden behind pews, pianos, under carpets, or, as is increasingly the case, in disused churches that are closed to the public. John Weever, the first antiquarian who sought to record commemorative monuments comprehensively in British churches, described monuments as things 'erected, made, or written, for a memorial'. Accordingly, tombs, effigies, brasses, ledger stones, and other wall tablets are included in this study under the term 'monument' (Weever, 1767: i). No monument index exists for the entirety of Britain, and it was not until the late twentieth century that historians began to understand monuments as tools from which to explore religious, social and cultural change (Sherlock, 2008: 1–13; Llewellyn, 2000: 1–3.) Adding Bristol as an important case study to this historiography, this article will argue that monuments are a useful historical tool and will use them to evidence the religious and social changes of the English Reformation. Principally, this article aims to understand how the English Reformation affected the way in which people were commemorated after death c. 1490–1640. Including approximately forty years on either side of the conventional English Reformation period, this date range recognises the Reformation as a long-term process in accordance with revisionist historians, and provides more data to illuminate the trends in Reformation commemoration (Tyacke, 1998: 1–2). This article will first demonstrate the doctrinal change evident in funerary monuments, before discussing the social changes that can also be read from such. Commemoration in post-Reformation Bristol was fundamentally religious in nature, but was increasingly varied in a way that illuminates the interaction of religious and social change.

Bristol

Since the 1950s the importance of localities to the experience of the English Reformation has been recognised, and the Reformation in Bristol has been extensively explored by Martha Skeeters, David Harris Sacks, and Joseph Bettey (Skeeters, 1993: 1–149; Harris Sacks,1992: 131–248; Bettey, 2001: 55–72). In 1542 Bristol became its own diocese, converting St Augustine's Abbey into Bristol Cathedral, and accordingly assuming city status. Bristol provides an important case study for two principal reasons. Firstly, Bristol is a significant city. With a sixteenth-century population of roughly 10,000, and as a bustling centre of trade, Bristol was more populous and wealthier than towns such as Exeter, Coventry and York (Fleming, 2001: 83). Secondly, Bristol is generally regarded to have been particularly reformist in nature from the early fifteenth century when there is evidence of a Lollard community. Revisionist historians have presented a nationwide image of a flourishing pre-Reformation religious culture, and Clive Burgess's work in Bristol in which he evidences keen lay involvement is convincing (Burgess, 1985: 46–65). Despite this, the certain existence of a small reformed element in the Bristolian elite by 1533 is enough to suggest that Bristol was at the centre of the Reformation and acted out its doctrinal debates (Fleming, 2001: 83). One key episode was the so-called 'Battle of the Pulpits' of 1533 when evangelical Hugh Latimer preached in Bristol at the invitation of local clergy in St Nicholas's, St Thomas's, and Black Friars, sparking opposition and debate. Bristol then, on the eve of the Reformation, was a thriving centre of both economic importance and religious debate. While historians of funerary monuments and local historians make use of the occasional illustrative Bristolian monument, no attempt that the author is aware of has been made specifically to analyse its funerary monuments across the Reformation period. This is, in part, due to the relative lack of surviving monuments. Visits to the surviving medieval parishes reveal that there are twenty-eight extant monuments in Bristol churches dating from 1490 to 1640. A comparably large Protestant populace may partially explain the relative lack of extant monuments since reformist iconoclasm did much to impoverish the number of pre-Reformation monuments in Bristol (Llewellyn, 2000: 76) During the Second World War Bristol lost three central medieval churches to bombings: Temple Church, St Mary le Port, and St Peter's. Moreover, many Bristolian monuments were lost during eighteenth- and nineteenth-century church refurbishment, when several churches were rebuilt. Of the eighteen Bristolian parishes recorded by William Worcester on his 1480 visit, ten parish churches survive, two religious houses out of seven remain, and two hospitals and one hospital chapel out of seven; there are no survivors of the additional ten chapels or hermitages (Neale, 2001: 29–30)[2]. Earlier records of monuments that have since been destroyed have been added to data collected from extant monuments in order to form a more complete profile of commemoration (Roper, 1931: 1–173; Roper, 1903: 215–87; Barrett, 1789: 246–609; Bristol Record Office, AC/36074/88a). The number of monuments under study has therefore been increased to eighty. This remains a small percentage of the estimated 4000 remaining funerary monuments nationwide dating from the 1530s to the Restoration of 1660 (Llewellyn, 2000: 6–7). However, limited evidence must not prevent an attempt to explore Bristol's monuments; rather, it necessitates one. An effort has been made to trace the original spatial context of the monuments, which has invariably been altered over time, and wills have been consulted where necessary for supporting information. Through the collection of photographic, pictorial and textual descriptions of monuments, it has been possible to perform some numerical analysis of stylistic features over time, to illuminate particular monuments for contextual analysis, and to suggest wider conclusions on the religious and social significance of this evidence.

Religion

It is fitting to begin an analysis of the effect of the Reformation on commemoration by exploring evidence of changed religious belief. The Catholic doctrine of purgatory was of central importance for posthumous commemoration in the late medieval religion (Duffy, 1992: 338). Pre-Reformation wills show that it was customary for people of all social ranks to leave money to receive requiem masses for their soul, in the form of obits, trentals, or diriges. An example comes from Richard Earle (d. 1491) who requested an obit on the anniversary of his death with 'placebo & dirige' at night and requiem mass the next day to be continued for no fewer than eighty years following his death (Wadley, 1886: 165). Chantry commissioning was also undertaken by the wealthier classes to ensure prayers and masses for their souls over the longer term. At the dissolution of the chantries in 1547 Bristol had thirty-five permanent chantries, twenty smaller endowments for lights, obits or masses, and thirty-three chantry priests (Bettey, 1979: 8). Pre-Reformation funerary monuments also evidence belief in purgatory. All seven extant Bristolian epitaphs from before 1490 request prayers or ask that God have mercy on their soul, both phrases that were associated with a belief in purgatory by Protestants (Hickman, 2001: 116). An early brass dated 1396, originally from Temple Church, directly implores: 'You who pass by whether old, idle ages or youth make supplication for me that I may hope to obtain pardon'. A later example of 1527 is the brass of Andrew Norton and his two wives, the epitaph of which translates from Latin to read 'the proprietor of the souls', God, 'my lord, have mercy on me' (Barrett, 1789: 519). Furthermore, as historian Nigel Saul argues, effigies positioned in prayer were understood by contemporaries from the twelfth century onwards as requests for prayers for the deceased's soul (Saul, 2009: 33). Before the Reformation, from 1490 to 1530, the effigies of all five tombs for which there is sufficient data are positioned in prayer. In Bristol, as across the country, pre-Reformation monuments belong to a rich religious culture of post-obitual commemoration which intended to invoke the prayers of the living to help the deceased's soul through purgatory.

Unlike requiem masses, chantries, obit lamps, and bede rolls, commemorative monuments were not specifically condemned by the Reformation governments. It was in their association with the doctrine of purgatory, which was officially abolished by Edward VI's government in 1547, and again in 1559 by Elizabeth I, that they came under attack by reformers. In Simon Fish's A Supplication for the Beggars, published as early as 1529, purgatory is dismissed because it is not mentioned in the Bible, as is accordingly the need to pray for the dead (Fish, 1878: 10–11). Protestant writers, such as Thomas Fuller (1608–61) expressed concern that monuments could skew the religious beliefs of the onlooker towards Catholicism (Llewellyn, 2000: 18). The Protestant rejection of purgatory formed the basis of iconoclastic attacks against funerary monuments of the 'Old Religion'.

No monument that seeks prayers for the dead, and accordingly implicates the doctrine of purgatory, survives in Bristol after 1522 and before the reign of the Catholic Mary I (r. 1553–58). It is tempting to view this as evidence of the early popularity of Protestantism in Bristol. However Catholic monuments may have been commissioned during this time and destroyed by Protestant iconoclasm (or by incidental destruction). In fact, the survival of a brass floor monument from1522 that implored prayers for the dead is notable, particularly since sixteenth-century Protestant iconoclasts were discernibly more likely to destroy recent Catholic monuments than those commissioned outside of social memory. Dedicated to John Brooke and his wife Joan of St Mary Redcliffe Church, the Latin epitaph reads, 'on whose souls may God have mercy'. Perhaps it was simply missed by fervent reformers, or perhaps the inscription was not as troublesome as more blatant calls for prayers. In any case it is clear that at least in 1522 the dying still commissioned tombs that implicated belief in purgatory. In the collections of Bristolian wills, it is not until the 1550s that the majority exclude requests for help for their soul, and are instead reformed in nature. By contrast in D. Hickman's study of Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire, 30 per cent of tombs in the 1560s explicitly imply Catholic belief in purgatory (Hickman, 2001: 117). Bristolians may have rejected purgatory faster than in this conservative region, but it must be stressed that the decline in references to this doctrine occurred gradually.

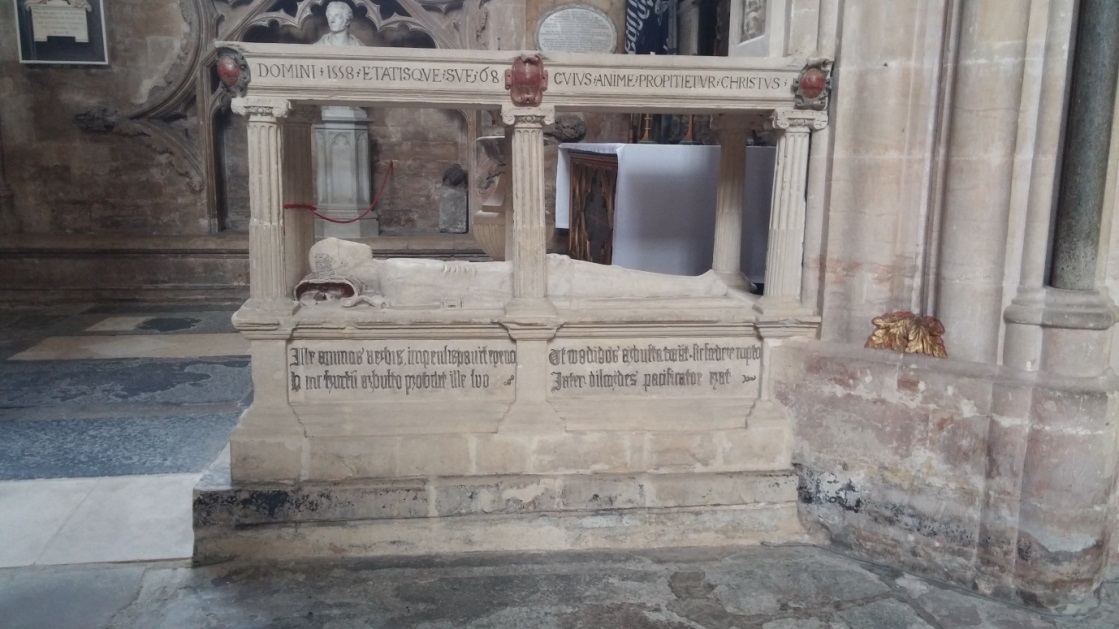

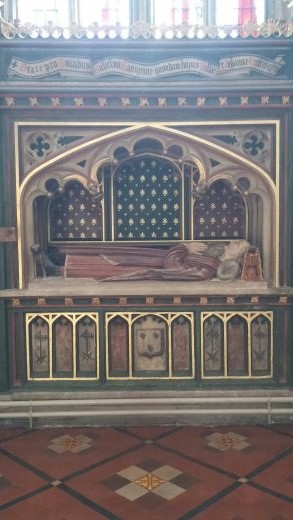

There are just two surviving epitaphs from 1551–80, both of which fall within the reign of Queen Mary I, and both of which suggest Catholic belief in purgatory. Edith Bush is commemorated by a plaque in Bristol Cathedral which directs the beholder to 'pray for the soule of Edith Bushe, otherwise Ashley' (Bettey, 1988: 172)[3]. Her death on 8 October 1553 came just a few months after Mary Tudor had proclaimed herself queen, and only days after her official coronation, emphasising the speed with which late medieval Catholicism was reassumed in some cases. The second epitaph, also in Bristol Cathedral, belongs to the tomb of Edith's husband, Bishop Paul Bush, who died in October 1558 (Figure 1). On the edge of the canopy the Latin inscription reads: 'upon whose soul may the Lord Christ have mercy', a phrase commonly associated with purgatory by contemporary Protestants (Hickman, 2001: 116).

A similar request for intercession which may indicate a belief in purgatory is found in Bishop Bush's will. He asked for the intercession of 'the blessed Virgin and mother of our Saviour Jesus Christ and all tholl ye company of heaven to … pray for me' (Will of Bishop Paul Bush, PROB 11/42A/23). Yet, Bishop Bush was consecrated as first Bishop of Bristol by Henry VIII on 25 June 1542 and in Edward's reign took advantage of the changed celibacy laws to marry. With the restoration of Catholicism in 1553 Bush refused to dissolve his marriage and was consequently deprived of his See in 1554 (Roper, 1903: 231–33). While never explicitly Protestant, Bush moved away from traditional Catholic beliefs, particularly in his understanding of the priestly role. Unlike his wife's direct call for the prayers of onlookers, Bush's call for holy intercession may have been a way of conforming to Mary Tudor's Catholic regime without directly implicating a belief in purgatory. His posthumous commemoration reflects the confusion and the diversity of religious beliefs of the Reformation period, something feasibly particularly apparent in the early years of Mary I's reign at the reinstatement of Catholicism[4].

Figure 1: Tomb and effigy of Bishop Paul Bush (d. 1558) located in the north choir aisle in Bristol Cathedral. Photo author's own.

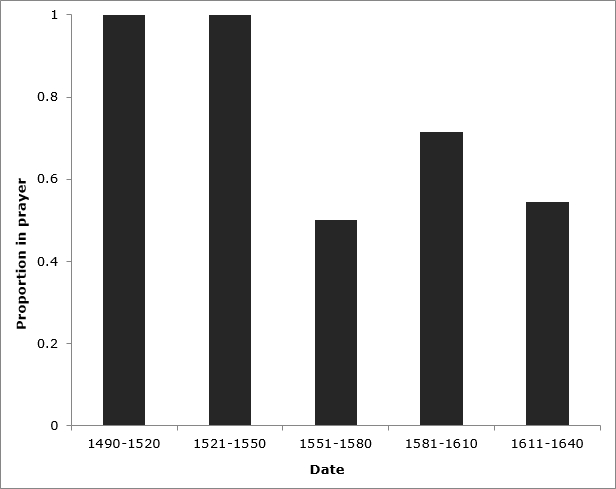

In Bristol no recorded monument references purgatory from the beginning of Elizabeth I's reign (November 1558) until the end of this study (1640). Elizabeth I issued a proclamation preventing the destruction of tombs in 1560. Because of this, and since epitaphs prior to her reign still survive with reference to purgatory, it is likely that this highlights a real trend in the decline of references to the Catholic doctrine. However, if, as with pre-Reformation effigies, those positioned in prayer were intended to invoke the prayers of the living for the deceased's soul, then oblique references to the doctrine of purgatory continue throughout the Elizabethan period. (Data from 1551 to 1580 is discounted since it references just two relevant effigies). While there is a clear decrease in the number of effigies at prayer from 1581, only two out of seven effigies from 1581 to 1610 are not at prayer (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Bar chart showing proportion of effigies in position of prayer. There is a decrease from 1581 which becomes more significant after 1611.

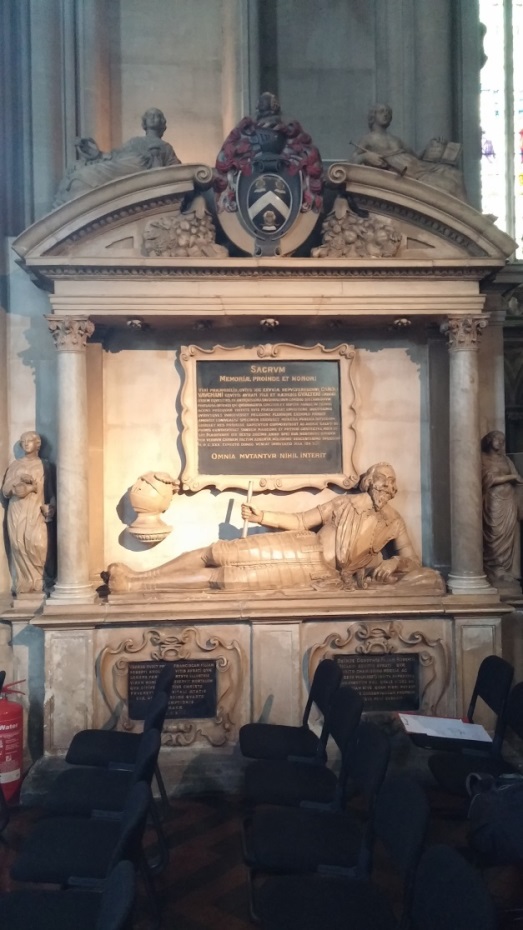

Nigel Llewellyn further argues that kneeling mourning figures were understood as figurations of the prayers requested for the soul of the deceased, and that they were technically illegal after the mid-1550s (Llewellyn, 2000: 105). However, kneeling figures in prayer normally face a Bible, and therefore imply Protestant emphasis on scripture. Kneeling mourning figures are found in two principal types: as secondary to the main epitaph on an altar tomb, or as the central effigy on a wall monument. The tomb of Sir Henry Newton (d. 1599) is a good example of the former. Below the recumbent effigy of Newton and his wife is a panel on which their two sons and four daughters are depicted kneeling with their hands in prayer, facing scripture. An example of the latter comes from St James's Priory, depicting Sir Charles Somerset on the left of the prayer desk, and his wife and daughter kneeling at prayer on the right. Across the country prayer desks were a common feature by c. 1600 (Llewellyn, 2000: 90). When prayer is depicted after the Reformation it is commonly to a prayer desk (three out of five from 1581 to 1610; six out of six from 1611 to 1640), whereas all effigies in prayer prior to the Reformation are recumbent, so praying hands did not symbolise intercessory prayer in the way that they did before the Reformation. This highlights the difficulties in understanding artistic symbolism. It is clear, though, that by the end of Elizabeth's reign funerary monuments had become more varied in style and no longer uniformly sought intercessory prayers. Llewellyn is among those historians who have claimed that post-Reformation monuments became more secular in signification (Llewellyn, 2000: 253). Indeed, the 1560 proclamation prohibited the destruction of monuments on the basis that they are 'set up for the only memory of them to their posterity … and not for any religious honour' (Wilkins, 1737: 221). A central argument within the present article, however, is that post-Reformation monuments are no less religious in signification. Fundamentally, they were commissioned to be situated within the church and would have formed a part of the fabric of parish worship. Moreover, the divide between 'religious' and 'secular' functions was not as clear-cut as it is today. Above all, post-Reformation monuments celebrate religious piety. The epitaph of Sir Charles Vaughan (d. 1630) in Bristol Cathedral praises the patron as an 'example to most in religion' who 'above all consulted his spiritual health' (Figure 3). Sir Henry Newton (d. 1599), whose tomb is in Bristol Cathedral, is similarly remembered for living his seventy years of life 'religiously toward God'. As in Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire, religious devotion was an important aspect of the virtues praised in post-Reformation epitaphs (Hickman, 2001: 113).

Figure 3: Tomb and effigy of Sir Charles Vaughan (d. 1630) located in the nave and originally in the eastern half of Bristol Cathedral. Photo author's own.

Changes in religious belief can also be read in post-Reformation monuments. It has already been established that the prayer desk is a common effigial figure on Elizabethan monuments. Furthermore, without the belief in purgatory, post-Reformation epitaphs express assurance that the deceased is in heaven, and normally with Christ. Martha Aldworth's (d. 1619) now-destroyed epitaph from St Peter's church is a good example: 'Wing'd with hope and love mount up to heaven' her soul, 'to be with whome is best of all', that is, Christ. (Roper, 1931: 143–44). Moreover, Elizabethan monuments commonly emphasise the resurrection of Judgement Day, to which reference is first made in the Bristol monuments in 1521. The epitaph of Sir Henry Newton (d. 1599), situated in Bristol Cathedral, reads: 'In assured hope of a Glorious Resurrection'. This may be in reference to the burial service given in the Book of Common Prayer of 1549 in which the priest carrying earth to the corpse says 'in sure and certain hope of resurrection' (http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/1549/BCP1549.pdf ). The tomb of Sir Charles Vaughan is decorated with an additional reclining figure who holds a trumpet and a book inscribed with the words 'Canet tuba enim', or, 'For the trumpet will sound'. These words are taken from 1 Corinthians 15:52, which continues, 'the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed'. At the back of the canopy a large framed square tablet is accordingly inscribed with the words, 'Expecto donec veniat immutatio mea', which translates as 'I wait until my change shall come' (Figure 3).

During the early part of Elizabeth I's reign, in which Protestant writers debated appropriate funeral commemoration, Bishop Gervase Babington included hope in their resurrection as a duty towards the dead (Babington, 1622, vol. iii: 124). Similar phrases to those found on monuments appear in Bristolian wills, particularly in the 1590s. For instance, Edmond Edwards (d. 1598) bequeaths his body to the chancel of Temple Church until 'the glorious resurrection of life everlasting' (Lang and McGregor, 1993: 41). As Llewellyn suggests, emphasis on the resurrection filled the need for a set of beliefs that allowed dominion over death after the collapse of the doctrine of purgatory and intercessory prayer (Llewellyn, 2000: 48–49). More research is needed to assess more meaningfully the doctrinal complexities in post-Reformation Protestantism found in commemorative monuments both on a national and local scale. In Bristol no epitaph can be said to be distinctively Calvinist and Laudianist in its language, although the latter's rejection of Calvinist predestination polarised English Protestantism in the early seventeenth century. Llewellyn suggests that an increase in allegorical figures in post-Reformation funerary monuments reflects a Puritan aversion to the supposed iconography of figurative effigies (Llewellyn, 2000: 246).Yet after the Reformation lifelike effigies exist alongside allegorical figures, such as the virtues, which may be explained as much by the influence of Renaissance Humanism as by Puritanism. Generally, however, it is clearly evident in Bristol's post-Reformation monuments that Elizabethan and Jacobean Protestantism emphasised the resurrection and the promise of heaven, which provided hope for the afterlife.

Society

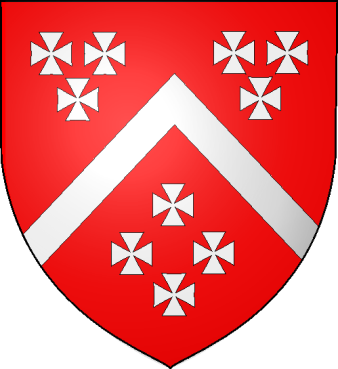

Having established the continued fundamentally religious nature of funerary monuments throughout the period, this article will now explore the social factors that shaped, and are reflected in, commemoration. Foremost, funerary monuments acted as signifiers of high social status. Bristol Cathedral was founded by the noble Berkeley family as an Augustinian monastery and the family chapel houses many fourteenth-century tombs including Thomas II Lord Berkeley (d. 1321), Maurice III Lord Berkeley (d. 1326), Maurice IV Lord Berkeley (d. 1378) and his mother Margaret (d. 1337). In the sixteenth century the noble Newton family also held a private family chapel in the cathedral. Sir Henry Newton (d. 1599) is commemorated in effigy alongside his wife Katherine, and his grandson Sir John Newton (d. 1661) is commemorated in the adjoining tomb. Additionally, John Newton's wife, Antholin (d. 1605) was commemorated by a tomb effigy in St Peter's church in Bristol (Roper, 1931: 134). The Newton family were significant landowners, notably from the fifteenth century of the Barrs Court estate, and Sir Henry was the owner of St Peter's Hospital in Bristol (Roper, 1903: 250)[5]. Although monuments commemorating those of high status are more likely to have been protected from destruction, Bristolian wills suggest that monument endowment was indeed reserved for the elite. In the Great Orphan book, which contains the wills of people from various social positions who died at a time when their children were young, there are no mentions of commemorative monuments (Wadley, 1886: 1–95). In the collection of Tudor wills by S. Lang and M. McGregor, only one, that of Elizabeth Williams (d. 1597), specifically makes reference to the stone that will cover her grave in St Peter's church (Lang and McGregor, 1993: 37). Commissioning of monuments is found, rather, in the wills of the wealthiest citizens which were proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury. This is also true in Essex: of F. G. Emmison's abstracted wills from this region from 1558 to 1577, only five reference commissioned funeral monuments (Marshall, 2002: 29). A rich historical literature focuses on heraldry found on commemorative monuments, which ensured that the exact details of birth and status were known to the beholder. Each Newton tomb recognises the importance of social status with the inclusion of their heraldic arms. This is also true for the Berkeley family. On the effigy of Thomas II Lord Berkeley, for instance, on the left arm a small heater-shaped shield displays the armorial bearings of the Berkeley family: a chevron in between 10 pattees, displayed in rows of 4, 2, 1, 2, 1 (Figure 4). Lineage was one of the most important features of the traditional elite classes throughout the period and this status was declared by heraldry on funerary monuments.

Figure 4: the Berkeley family heraldry. Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/BerkeleyE_CoA.png

On a national scale Llewellyn has shown that there is a steady upward curve from the start of Elizabeth's reign in the number of monuments erected (Llewellyn, 2000: 7). Similarly, Hickman's study of Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire evidences an increase in the number of laity buried in the chancel of the church, an area formerly reserved for the burial of clerics or of laymen of the highest social class (Hickman, 2001: 112). In Bristol, there is a similar trend in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries as yeomen and urban workers requested burial within the church next to their individual pews. A higher number of people appear to have been able to afford commemoration, and to commission monuments. This trend may correspond to the steady recovery of the economy after it faltered in the early sixteenth century. Unlike neighbouring Somerset which was ruled by landed nobility, Bristol was dominated by a significant merchant aristocracy throughout the period (Jordan, 1960: 5). In the late fifteenth century the merchant guild and the Corporation, or local government, were essentially one body (http://merchantventurers.com/about-us/history/).William Canynges (d. 1474), whose epitaph describes him as 'ye Richest Marchant of ye towne of Bristow', was one of the greatest merchants of Bristol, who opened a lucrative cloth trade with the Baltic. In 1432 he started his civic career as bailiff of Bristol, and was then five times mayor of Bristol and three times MP, before becoming a priest in 1468 following the death of his wife (Roper, 1931: 122). The number of merchants who commissioned monuments rose steadily in the post-Reformation period (Table 1). If we consider that many of those who are identified as mayors or aldermen on their monuments were also merchants, as was increasingly the case by the early seventeenth century, the rise in the number of merchants who commissioned tombs is even greater (Harris Sacks, 1992: 185). In the hundred-year period following 1640 modest plaques are abundant, normally following the simple pattern: 'here lyeth the body of', name, occupation, and date of death. Under Henry VIII (r. 1509–47) both funerals and heraldry came under tighter control of the state to ensure that grander commemoration (including larger monuments) was reserved for the noble classes (Llewellyn, 1990: 222). It seems likely that these early restrictions reflected concern among the traditional landed gentry and nobility of the increased accessibility of funerary monuments, as well as prestigious burial locations, to a growing mercantile elite.

| Date | Knight/Squire | Merchant | Brewer | Mayor/Alderman | Ecclesiastic | Law | Other | Total no. monuments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1490–1520 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| 1521–1550 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 1551–1580 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 1581–1610 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 19 |

| 1611–1640 | 5 | 10 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 31 |

| Total no. occupation | 10 | 23 | 5 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 5 | 67 |

Table 1: Table showing types of occupation on monuments. Merchants and mayors/aldermen became steadily more represented.

Although entry requirements into the gentry had always been ambiguous, Felicity Heal and Clive Holmes propose that whereas gentry status was traditionally built upon heraldry and claims to land, it was increasingly understood in the post-Reformation period to be based on wealth, offices, and the expression of humanist virtues (Heal and Holmes, 1994: 7). Although the tombs of richer merchants, like Canynges, could boast family arms, 'three Moors' heads with a wreath around their temples' (Figure 5), merchant tombs and monuments are often decorated with individual merchant marks. For middling merchants these acted in much the same way as the heraldry that was available for merchants of great families. However, merchant marks commemorated the individual rather than the family lineage. A ledger stone in the crypt (or 'crowde' as it was known in Bristol) of St John the Baptist is a good example. Hugh Griffin (d. 1597) is commemorated by a simple stone with the words 'Here rested the body of Hugh Griffin Merchant …' and an engraving of a large merchant mark. Heraldry and family status was still important in commemorative monuments, but individuals could receive high social status by achieving wealth, and additionally by holding office. Perhaps more than elsewhere, Bristol's thriving mercantile trade meant that a higher number of wealthy individuals could be commemorated within the church in the sixteenth century.

Figure 5: Tomb of William Canynges located in the south transept of St Mary Redcliffe Church. Showing the Canynges' coat of arms below the effigy along with a merchant mark. Photo author's own.

Elizabethan Catholics argued that there was a decline in charitable giving as a result of the abandonment of purgatory (Marshall, 2000: 280). Indeed, the late medieval religion maintained that by receiving the prayers of the living, charitable acts would be rewarded by reduced time spent in purgatory. Pre-Reformation wills are packed with charitable bequests to the parish church, and it was common for alms to be distributed to the poor at the funeral, and at further posthumous masses. An early example comes from Isabel Barstaple (d. 1411), the wealthy widow of John Barstaple who was burgess of Bristol, who donated £10 'to the poor' as well as white cloth to the value of £8 for the poor to follow her body to its burial (Wadley, 1886: 86). However, one of the primary commendations on Elizabethan and Jacobean epitaphs is that of being charitable to the poor, references to which are actually only apparent after 1540 in the Bristolian monuments. Emphasis on being charitable on 'Protestant' monuments may have been a reaction to Catholic criticism of Protestants. It also reflected a real increase in giving to the poor. Simon Fish was among those Protestant writers who argued that revenues that would have been spent on post-mortem provision go to the poor. W. K. Jordan's famous study on charitable giving over the period 1480–1660 argues that in no other place were merchants more charitable than in Bristol where they dominated the aristocracy (Jordan, 1960: 12). The use of charity as a motif of remembrance was above all attractive for mercantile elites who could not boast the lineage of landed gentry (Marshall, 2000: 284).

Robert Aldworth (d. 1634), whose tomb was situated in St Peter's, and who is commended for giving to the poor in his epitaph, was a merchant and sugar boiler at St Peter's House as well as sheriff of Bristol in 1596 and mayor in 1609 (Roper, 1931: 146). An increase in mercantile wealth and civic authority in Bristol in the sixteenth century coincided with the increase in charitable bequests. Jordan argues that the secularisation of bequests over the Reformation period is most clearly visible in Bristol. However, he limits religious bequests as those given directly to the Church (Jordan, 1960: 10). Bequests made to seemingly 'secular' causes should not be seen as non-religious. To Calvinist Protestants, for instance, charitable giving was evidence of election, and it therefore reflected a distinctly religious concern. In fact, charity was recognised and celebrated on monuments as a universal Christian moral and obligation that declared the greatness of the patron. There was more continuity than change in charitable giving over the period.

Conclusion

Before the Reformation, funerary monuments belonged within an overarching practice of commemoration, which included requiem masses, funerals, and bede rolls, and which sought above all the prayers of the living in order to hasten the soul of the deceased through purgatory. From the outset, the doctrine of purgatory was central to the Protestant attack on Catholicism, but as pre-Reformation commemorative culture was torn up at the roots, funerary monuments continued to be commissioned. They endured because their purpose extended beyond the immediately 'religious', acting as displays of social status and personal values.

However, this article has shown that after the Reformation funerary monuments did not become more 'secular'. Instead they reflected changes in religious doctrine, such as an increased emphasis on the resurrection. Furthermore, despite evidence that Bristol had a strong reformist minority, Catholic beliefs did not decay in the mainstream until the 1550s. This article has also discussed the social changes evident in post-Reformation commemoration. It has argued that while monuments had always been reserved for the elite class, after the Reformation the changed criteria for such, including wealth, office holding and charitable giving, increased the number of monuments commissioned. Bristol's merchant community are particularly well represented in monuments as a result. Monuments provide an important source for understanding the religious and social changes in post-Reformation England. It is hoped that this article will act as a springboard for much-needed further research into funerary monuments in Bristol. Although they commemorated a small percentage of the population, monuments are significant because they formed a focal point of parish worship from which religious and social values were presented to the parish laity. As commemoration changed so too did remembrance, from the act of praying for the soul of the deceased, to an internal remembrance of the deceased's personal attributes. The meaning behind the wish for the soul to 'be remembered' on a 1396 brass is distinct from the 'undying memory' invoked by the epitaph of George Upton (d. 1608), for instance. Throughout, however, monuments were commissioned in order to leave something in the natural world, and to quench the fear born from the uncertain nature of death, both for the dying and the living.

Acknowledgements

I am above all hugely grateful to Professor Peter Marshall for his continual support and advice. Thanks are given to the numerous church wardens and heritage volunteers who kindly allowed access to Bristol's churches.

List of illustrations

Figure 1: Tomb and effigy of Bishop Paul Bush (d. 1558) located in the north choir aisle in Bristol Cathedral. Photo author's own. Figure 2: Bar chart showing the proportion of effigies in position of prayer. Figure 3: Tomb and effigy of Sir Charles Vaughan (d. 1630) located in the nave and originally in the eastern half of Bristol Cathedral. Photo author's own. Figure 4: The Berkeley family heraldry. Image in the public domain, source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/BerkeleyE_CoA.png. Figure 5: Tomb of William Canynges located in the south transept of St Mary Redcliffe Church. Photo author's own.

List of tables

Table 1: Table showing types of occupation on monuments. Merchants and mayors/aldermen became steadily more represented.

Endnotes

[1] Eleanor Barnett completed her degree in History at the University of Warwick with first-class honours in 2015. She is now living in Cambridge to undertake an MPhil in Early Modern History at Christ's College where she will continue to pursue research into her fascination with the history of the body and the English Reformation.

[2] Eight parish churches survive in their original locations: All Saints, St John the Baptist, St Stephen, St Philip, St Mary Redcliffe, St Nicholas, St Thomas and St Michael on the Mount Without (however, the last three were almost entirely rebuilt in the late eighteenth century). In the late eighteenth century St. Werburgh's church was rebuilt at a new location, and Christ Church and St Ewen were demolished and rebuilt as one parish church. The two surviving religious houses are St James' Priory, and St Augustine's Abbey the Great (now Bristol Cathedral). The one hospital chapel is that of St Mark's (known as The Lord Mayor's Chapel) and originally a part of the Gaunt's Hospital. Holy Trinity Hospital, founded by John Barstaple in the late fourteenth century, survives but is now used as residential accommodation, and St Bartholomew's Gateway survives but contains no monuments.

[3] The use of Edith Bush's maiden name in her epitaph is likely to reflect the questionable status of her marriage to Bishop Paul Bush after the restitution of Catholicism under Mary I.

[4] Two records of Bristolian monuments created between 1551 and 1580 make no reference to the afterlife at all: John Smith in St Werburgh's church (d. 1556) and James Chester of St James' Priory (d. 1560) (Barrett, 1789: 484, 393). This may suggest that during this period there was confusion or fear about to openly expressing Catholic or Protestant faith on commemorative monuments.

[5] The Searchfields and the Vaughan families are further Bristolian examples of traditional gentry families that are commemorated by funerary monuments. Rowland Searchfield (d. 1622) was Bishop of Bristol and is commemorated by a small plaque in the cathedral, and William Searchfield and Anne Searchfield are commemorated by a brass plaque in St Mark's. Sir Charles Vaughan's tomb (d. 1630) is situated in Bristol Cathedral, while Catharine Vaughan (d. 1694) is commemorated by a wall monument in St Mark's.

References

Babington, G. (1622), Workes, iii, Miles Smith, ed., London: privately published (originally published 1615)

Barrett, W. (1789), The History and Antiquities of the City of Bristol, Bristol: William Pine

Bettey, J. H. (1979), Bristol Parish Churches during the Reformation, c. 1530–1560, Bristol: Bristol Branch of the Historical Association

Bettey, J. H. (1988), 'Paul Bush, the first bishop of Bristol', Transactions of the Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 106, 169–72

Bettey, J. H. (ed.) (2001), Historic Churches and Church Life in Bristol, Bristol: Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society The Book of Common Prayer (originally published 1549), available at http://justus.anglican.org/resources/bcp/1549/BCP1549.pdf, accessed 12 September 2014 Bristol Record Office, AC/36074/88a, Volume of heraldic and antiquarian notes and researches, possibly compiled by one H. Savage, 1669

Burgess, C. (1985), 'For the Increase of Divine Service': Chantries in the Parish in Late Medieval Bristol', Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 36 (1), 46–65.

Duffy, E. (1992), The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c. 1400–c. 1580, New Haven: Yale University Press

Fish, S. (1878), A Supplication for the Beggars, London (first published 1529).

Fleming, P. (2001), 'Sanctuary and authority in pre-Reformation Bristol', in Bettey, J. (ed.), Historic Churches and Church Life in Bristol, Bristol: Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, pp.73–84

Harris Sacks, David (1992), The Widening Gate: Bristol and the Atlantic Economy, 1450–1700, Berkeley: University of California Press

Heal, F. and C. Holmes (1994), The Gentry in England and Wales 1500–1700, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

Hickman, D. (2001), 'Wise and Religious Epitaphs: Funerary Inscriptions as Evidence for Religious Change in Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire, c. 1500–1640', Midland History, 26 (1), 107–27

Jordan, W. K. (1960), 'The forming of the charitable institutions of the West of England: a study of the changing pattern of social aspirations in Bristol and Somerset, 1480–1660', Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 50 (8), 1-99

Lang, S., and M. McGregor (eds) (1993), 'Tudor Wills proved in Bristol, 1546–1603', Bristol: Bristol Record Society

Llewellyn, N. (2000), Funeral Monuments in Post-Reformation England, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Llewellyn, N. (1990), 'The Royal Body: Monuments to the Dead, For the Living', in Gent, L. and N. Llewellyn (eds), Renaissance Bodies, London: Reaktion Books, pp. 218–40

Marshall, P. (2002), Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Neale, F. (2001), 'William Worcestre: Bristol Churches in 1480', in Bettey, J. (ed.), Historic Churches and Church Life in Bristol, Bristol: Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, pp. 29–54

Roper, I. M. (1931), The Monumental Effigies of Gloucestershire and Bristol, Gloucester: privately printed by Henry Osborne

Roper, I. M. (1903), 'Effigies of Bristol', Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society, 26, 215–87

Saul, N. (2009), English Church Monuments in the Middle Ages, Oxford: Oxford University Press

Sherlock, P. (2008), Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England, Aldershot: Ashgate

Skeeters, M. (1993), Community and clergy: Bristol and the Reformation, c. 1530–c. 1570, Oxford: Clarendon Press The Society of Merchant Ventures, 'History', available at http://merchantventurers.com/about-us/history/, accessed 12 September 2014

Tyacke, N. (ed.) (1998), England's Long Reformation 1500–1800, London: UCL Press Limited

Wadley, T. P. (ed.) (1886), Notes or Abstracts of the Great Orphan Book and Book of Wills, Bristol: C. T. Jefferies and Sons

Weever, J. (1767), Ancient Funeral Monuments of Great Britain, Ireland, and the Islands adjacent, London: W. Tooke (first published 1631)

Wilkins, D. (1737), Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae –Volumen Quartum, London: privately published Will of Bishop Paul Bush, proved 1 December 1558, The National Archives, Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PCC) wills, PROB 11/42A/23

To cite this paper please use the following details: Barnett, E. (2015), 'Commemorative Funerary Monuments in Reformation Bristol c. 1490–1640', Reinvention: an International Journal of Undergraduate Research, Volume 8, Issue 2, http://www.warwick.ac.uk/reinventionjournal/issues/volume8issue2/barnett Date accessed [insert date]. If you cite this article or use it in any teaching or other related activities please let us know by e-mailing us at Reinventionjournal at warwick dot ac dot uk.