Article 4

by Mirko Draca

Unregistered or ‘shadow’ lobbying is a booming business, and it’s threatening the transparency of US law making.

The lobbying of government by special interest groups is legal in the US – and as an industry, it’s thriving. Spending on registered lobbying activity rose by 68% between 1998 and 2013, from $1.9 billion to $3.2 billion.

To maintain the integrity of the democratic process, US law requires lobbying activity to be registered according to the Lobbying Disclosure Act (LDA, 1995). But in recent years critics have called out a lack of transparency. Donald Trump in his 2016 presidential campaign, for example, included a battle cry to ‘drain the swamp’ of shadow lobbyists (only to come under criticism during his Presidency over claims his staff were involved in shadow lobbying).

But is shadow lobbying a regular practice in US politics? And if so, what is the scale of the issue?

The LDA defines lobbyists as people who have than one lobbying contact, are paid for their work and spend more than 20% of their time lobbying. Workers who meet this definition must report their meetings and activities every three months to the Government Audit Office.

To find out just how much lobbying is done off the books, we monitor politicians and staffers leaving congressional posts and joining firms with lobbying practices between 1998 and 2012. From this group, we compare ‘shadow lobbyists’ (those who do not register as lobbyists) officially registered lobbyists to measure their effects on firm revenue. We use data from lobbying reports, congressional staff databases and firm revenues.

We find that shadow lobbyists account for $149 million dollars in additional firm revenue across the sector: a 6.4% revenue boost. Firms can expect a 10–20% increase in revenue for each shadow lobbyist they hire. This revenue uplift is equivalent to hiring one full time mid-level registered lobbyist.

It’s hard to reconcile that 20% of one shadow lobbyist is as effective as 100% of a registered lobbyist. The evidence strongly suggests that shadow lobbyists are spending more than 20% of their time on lobbying activities.

The data shows that shadow lobbyists are concentrated in large firms with more than ten registered lobbyists, where it is easier for them to leverage their contacts and experience – or hide their activity. Around 40% of shadow lobbyists work for these large firms, which make up just 129 out of 4600 businesses in the industry.

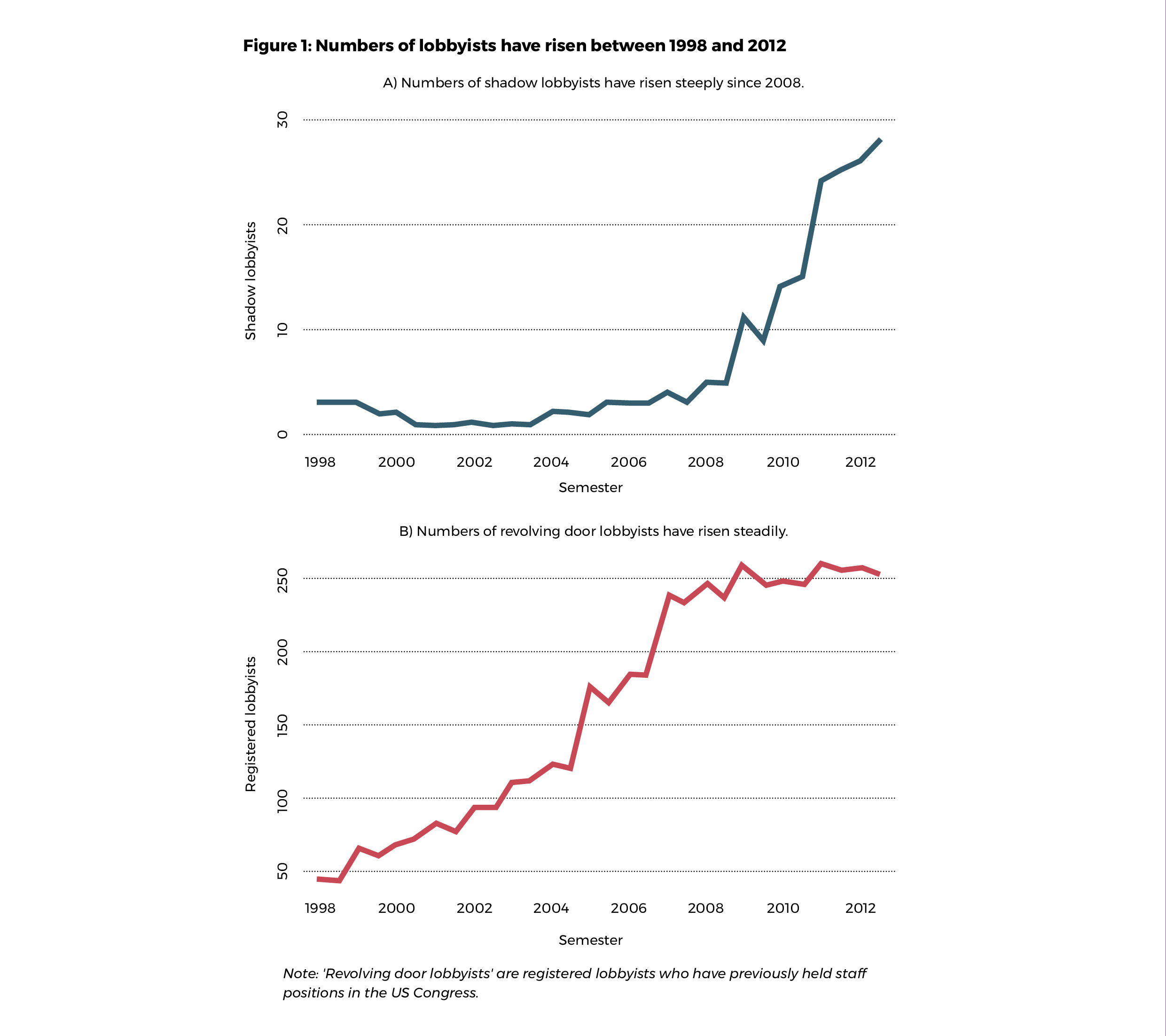

We find that both shadow lobbyists and registered lobbyists have risen across the period, but shadow lobbyists have particularly grown since 2008 (Figure 1). A possible reason for this shift is that in 2007 the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act required congressional staffers to wait 12–24 months before they could take up a lobbying position. Similar restrictions were put in place for people with lobbying experience wishing to take up a position in the Administration. This may have deterred some lobbyists from officially registering their activity.

Revenue growth is concentrated among firms who hire shadow lobbyists. By the end of the period we study, firms with shadow lobbyists are taking on $5–6millon – double that of firms with no shadow lobbyists. There are lots of possible reasons for this gap. We estimate that about 7% of the gap can be explained by the growth of shadow lobbyists.

The evidence suggests that the LDA is not effective in ensuring that lobbying activity is fully recorded. The 20% lobbying boundary is a self-reported measure that cannot easily be checked and verified. In fact, in a report in 2015, the Government Audit Office said that it was not obliged to monitor rule breaking or to seek out evidence of shadow lobbying. As a result, individuals can avoid registering as a lobbyist without fear of reprisal.

It is worth noting that our evidence for shadow lobbying may only be the tip of the iceberg. Our data does not cover organisations that do not have a lobbying practice, such as think tanks. There may be many more unregistered ex-congressional staff lobbying in organisations like these.

As lobbying continues to drive big business revenue in the US, better monitoring through the LDA will be essential to keep US political decision-making transparent.

Publication details

d’Este, R., Draca, M., Fons-Rosen C. (2023). Shadow lobbyists. CAGE Working Paper (no. 652).

About the author

Mirko Draca is CAGE Director and Professor of Economics at the University of Warwick.