ESLJ Volume 1 Number 2 Articles

Ambush Marketing: More than Just a Commercial Irritant?

JANET HOEK and PHILIP GENDALL

[Janet Hoek is Associate Professor of Marketing and Philip Gendall is Professor of Marketing and Head of the Department of Marketing. Both are at Massey University, New Zealand.]

Abstract

Although marketers have described ‘ambush’ marketing as a parasitic activity that encroaches on legitimate sponsorship, their claims often provide no basis for legal action. This article examines instances of alleged ambushes and how these fit within a wider legal framework. Ambushing appears to encompass legitimate competitive behaviour through to passing off and misuse of trademarks. Marketers concerned about ambushing should remove loopholes from contracts to minimise the opportunities open to competitors. They would also do well to learn more about the legal status of their claims and to separate these from any feelings of irritation evoked by their competitors’ behaviour.

Keywords: marketing, ambush, sponsorship, trademark

This is a refereed article published online on 8th February 2005.

Citation: Hoek, Janet and Gendall, Philip 'Ambush Marketing: More than Just a Commercial Irritant?', Entertainment and Sports Law Journal (ESLJ) Volume 1, Number 1, <http://www.warwick.ac.uk/go/eslj/>.

1. Introduction

Numerous researchers have documented the phenomenal growth in sponsorship that has occurred over recent decades.[1] Many have also noted changes in the objectives set for sponsorship and its increasingly commercial orientation.[2] Hoek concluded that managers no longer see sponsorship as a philanthropic gesture, but expect it to provide a financial return.[3] Because of this increasingly profit-oriented perspective, management of sponsorship has become more sophisticated, and managers now appraise sponsorship options carefully to ensure they complement the sponsoring brand or organisation.

Yet, while this increasing sophistication has led to innovative alliances between sponsors and teams or events, it has also heightened the competition for rights to high-profile events, such as the Olympic Games. This competition has had at least two quite different results. First, it has enabled event owners to charge premium prices for sponsorship rights.[4] However, while the heightened status of global sponsorship has greatly increased the value of international events, it has also reduced the number of companies able to afford naming (or other) rights. Some researchers have suggested that companies unable to fund sponsorship rights, or that have failed in their attempt to secure these, have resorted to undermining the value and benefits of the sponsorship rights they failed to obtain.[5] Thus, a second consequence of commercial sponsorship’s expansion has been an increase in what has become colloquially known as ‘ambush marketing’.

Although many marketers have reacted strongly to alleged instances of ambushing behaviour, considerable ambiguity surrounds this concept. In particular, marketers’ discussion of ambush marketing suggests it includes what are arguably normal competitive practices. Thus despite the rancour this practice arouses, there is surprisingly little discussion of its legal status, or of whether it is more than just a commercial irritant. This article examines ambush marketing, the range of behaviours to which the term has been applied, and the legal status of these behaviours. It begins by documenting the growth in alleged ambushing before turning to examine specific cases in which event owners have challenged alleged ambushers, and the legal precepts on which these cases have turned. Finally, it evaluates whether aspects of ambush marketing have become more than exasperating competitive tactics, and the remedies available to event owners and sponsors.

2. Evolution of Ambush Marketing

According to Sandler and Shani, ambush marketing commenced in 1984, when the Los Angeles Olympics became the first Olympic Games to market sponsorship in an overtly commercial manner.[6] Whereas in the past, many sponsors could obtain rights to associate their brand with the Olympics, the 1984 Games developed sponsorship packages that entitled official sponsors to exclusivity within their specific category. Researchers have suggested that aggrieved parties who bid unsuccessfully for sponsorship rights, as well as those who could not muster the financial resources required to compete at this level, turned to ambushing as a means of maintaining some association with the event.[7]

Early discussions of alleged ambush marketing implied that it was a premeditated activity, designed deliberately to deprive an official sponsor of the benefits they would otherwise receive.[8] Thus Meenaghan recently described ambushing as occurring when ‘another company, often a competitor of the official sponsor, attempts to deflect the audience’s attention to itself and away from the sponsor. This practice simultaneously reduces the effectiveness of the sponsor’s communications while undermining the quality and value of sponsorship opportunity being sold by the event owner’.[9]

This definition implies that any activity successfully ‘deflect[ing] the audience’s attention to itself and away from the sponsor’ effectively ambushes that event. The ultimate consequence of any deflection may be that consumers mistakenly attribute sponsorship of an event to the ambusher, rather than to the true sponsor.[10] However, researchers have differed in their views on how this confusion may affect consumers. While Tripoldi and Sutherland suggest that it might change consumers’ purchase intentions and subsequent behaviour, Shani and Sandler argue that ambush marketing had little material effect on consumers’ behaviour.[11]

In keeping with the very comprehensive definitions of ambushing advanced, marketing researchers and commentators have viewed ambushing as virtually any attempt by a competitor to engage in promotion activities during a sponsorship. Thus, companies undertaking advertising while a competitor’s sponsorship was current were considered ambushers, particularly if they used media spots that ran during broadcasts of the sponsored event.[12] Similarly, some researchers have argued that initiatives to secure alternative sponsorships, or sub-categories of sponsorship such as broadcast rights, will ambush the higher-level sponsor.[13] The content of advertisements, particularly the use of images or logos associated with the event, has also attracted criticism.[14] Some researchers have also commented on the use of official tickets as prizes in sweepstakes or other competitions, and have suggested that this may also imply an official association that may not actually exist.[15]

Overall, marketers suggest that ambush marketing encompasses a wide range of different actions, including the use of simultaneous promotions, purchase of sub-category rights, and misappropriation or forgery of trademarks available only to official sponsors.[16] Yet, from a practical point of view, marketers’ views on what constitutes ambushing are irrelevant. The key issue is whether alleged ambushing comprises legitimate competitive activities or whether these activities breach fair-trading or other relevant statutes.

The comprehensiveness of Meenaghan’s definition thus creates some logical difficulties, as few would argue that success in securing sponsorship rights entitled the sponsor to a promotion environment free of any competing messages. While marketers may have described ambushing as anything that deprives an official sponsor of the benefits they have purchased, considerable ambiguity still exists over the status of alleged ambushing behaviours. More importantly, because the range of activities described by marketers as ambushing do not always have a sound legal basis, the grievances they outline are not always paralleled by actions they can take. The following section examines alleged instances of ambushing in more detail and discusses the remedies available to sponsors and event owners.

3. Alleged Instances of Ambushing Behaviour

There can be little doubt that companies that have not paid for sponsorship rights or licence fees, but that nevertheless run promotions suggesting they are associated with the event, irk the official sponsors. However, irritation alone does not provide sufficient grounds for legal action, as the following examples illustrate.

3.1 Simultaneous Advertising and Promotion Campaigns

Meenaghan has suggested that heavy competitive advertising throughout the duration of an event could ambush that event because viewers or readers may associate the event with the advertiser, rather than with the official sponsor.[17] This is particularly likely when the official sponsor has undertaken little or no advertising to promote their sponsorship.

Graham noted several instances where rivals of a sponsor had engaged in wide-ranging competitive promotions.[18] For example, he notes American Express purchased advertising space on Barcelona’s Hotel Princess Sophia’s room key tags - the hotel was apparently the official IOC residence and Visa, not American Express, was the official credit card. Similarly, Nike purchased prominent billboard space overlooking Atlanta’s Olympic Park - Reebok was the official shoe sponsor.

Unfortunately, despite the annoyance the competitors’ actions may cause, exploitation of media opportunities alone does not breach fair-trading or other legislation. Indeed, the design and implementation of simultaneous promotions seems part of the cut and thrust of a normal competitive environment. For example, manufacturers frequently run advertising and in-store promotions that compete directly and it is difficult to see how these actions alone constitute anything other than routine commercial behaviour. As a result, the mere existence of these promotions seems unlikely to give rise to strong actions; however, their effect on the level of exclusivity provided in the contract and their content may do so. The following sections examine these questions further.

3.2 Procurement of Sub-Category Rights

Where companies have not obtained rights to an event, they may be able to purchase rights to smaller sponsorships that still provide many opportunities for airtime.[19] For example, companies that do not have official Olympic sponsor status may purchase the rights to sponsor the media broadcasting a specific event, or they may sponsor an individual competing within that event. From the official sponsor’s point of view, these arrangements encroach on their exclusivity, and so may diminish the overall value of the sponsorship to them.

Graham cites several examples where competitors of official sponsors obtained broadcast rights to the events their competitor sponsored.[20] Yet, although several researchers have cited this behaviour as a prime instance of ambushing, it is difficult to see how advertisers can be held to account if the sponsorship contracts did not specifically exclude competitors. Where sponsorship contracts do contain provisions along these lines, competitors’ access to sponsorship rights would constitute a breach of the contract and the original sponsor would be entitled to the remedies prescribed by the contract. Ultimately, determination of the original sponsor’s claim would depend on the wording of the contract.

Cases involving conflicts between sponsors of an event and sponsors of the media rights to that event have led some major event owners, such as the IOC, to implement stricter contracts that ensure official sponsors have first right of refusal to media opportunities. As some commentators have pointed out, however, the cost of securing sponsorship rights may leave companies with few funds to promote their status.[21] In addition, where official sponsors decline to secure media rights, they and the event owners may be unable to prevent competitors from obtaining them.

These situations highlight an implicit conflict of interest between event owners, who wish to maximise the revenue they can obtain from the event, and sponsors, who wish to protect their investment. Event owners have arguably been slow to react to this conflict, perhaps because, as some researchers have suggested, to do so would reduce their revenue stream.[22] Ultimately, sponsors’ increasing concern that these conflicts devalue the rights they have purchased means event owners must pay more attention to the manner in which they structure their sponsorship packages and contracts. Given that conflicting sponsorships still occur, and that these are widely cited as examples of ambushing, changes to sponsorship contracts appear well overdue.

In the case of conflicting sponsorship arrangements, official sponsors may not have been able to claim against their competitors, since the promotion packages they secured were legally available to them. They may, however, have grounds for claiming against the event owner, for failing to deliver full sponsorship benefits. Clearly, actions taken on the latter grounds would also depend on the substance of the contract and any related documents outlining benefits sponsors could expect. Growing evidence that sponsors may claim against event owners who failed to deliver the benefits they could reasonably expect may mean it is no longer in the interests of event owners to turn a blind-eye to the competitive arrangements that have been possible.[23]

3.3 Advertising and Promotion Claims and Images

Undertaking competitive promotions, even securing competitive sponsorship contracts, is not in itself illegal. Marketers must therefore examine the content of the promotions, particularly the claims made or implied and the imagery used; if these create confusion among consumers, they may form the basis for action. This is more likely to be the case where the visual devices used are registered trademarks, or specific words available only to official sponsors. Unauthorised use of these entities would seem to constitute clear grounds for action.

Bean discussed sophisticated promotion campaigns that included oblique, but unambiguous, references to the event site.[24] These advertisements referred to the event or the location in generic terms, and so did not breach licence agreements that permit only official sponsors to use the exact names and details of the event. The promotions thus linked the competitive brand with the event location and, in so doing, may have confused consumers as to the real sponsor.

Bean also noted that where these cases have come to court, companies have protected themselves by using disclaimers. That is, the promotions have included words to the effect that the advertiser is not claiming official sponsor status, and the courts have considered that these offset the messages implied in the body of the advertisement.

To illustrate this particular aspect of ambushing, Bean drew on NHL v. Pepsi 92 DLR.4th 349 (BC 1992). This case alleged that Pepsi’s ‘Pro-Hockey Playoff Pool’ deliberately created confusion with the NHL Stanley Cup Playoffs, which Coca-Cola sponsored. Pepsi ran a strong advertising campaign to promote a competition that required consumers to match NHL Playoff results with information found on Pepsi bottle caps. Pepsi took some precautions to protect against claims of passing off. They did not refer to its competition by the official title, which presumably was only available to sponsors for use in their promotion material. Pepsi also included disclaimers on its merchandising and advertising material to the effect that the items were not associated with the NHL. In addition, Pepsi did not use the teams’ trademarked names, but referred to them generically, through their city.

The NHL’s action alleged trademark infringement, passing off and interference with the NHL’s contractual arrangements. After reviewing the evidence, the Supreme Court of British Columbia dismissed the action and specifically noted the use of disclaimers to convey the fact that it was not associated with the NHL.[25]

Pepsi’s campaign clearly involved several activities described as ambushing. It made use of a similar promotion, scheduled to run simultaneously with the original event, and employed a variety of supporting promotions that also paralleled aspects of the original event. Overall, despite the stand adopted by the NHL, Pepsi’s care in not using registered trademarks, and their disclaimer, meant their conduct fell short of breaching Canadian law.

3.4 Trademark Misappropriation

It is perhaps in the area of trademark misappropriation that the most interesting cases of alleged ambushing have arisen. As Bean noted, few advertisers deliberately copy marks they know to be registered, since this would provide immediate and clear grounds for action.[26] However, competitors may design variations of registered images so these differ from the registered mark and yet provide sufficient similarity to create confusion in the minds of consumers. Thus, in the example cited earlier, Pepsi could not use the trademarked NHL team names and so used the generic names of cities to identify the teams from those cities. Unsurprisingly, because the team name typically included the city name, use of the city name alone was sufficient to identify clearly the NHL team.

Where competitors have either misappropriated trademarks or where they have designed marks that are not registered trademarks, but that effectively pass them off as the trademark owner or licensee, the legitimate owners and users can take a variety of actions. In particular, they can make a claim under trademark legislation and/or unfair competition statutes, and they can allege passing off. As the Pepsi case reveals, the success of these actions depends very much on the nature of the marks used, and the extent to which consumers would be likely to misinterpret these. The following examples illustrate the creative extension of trademarks and discuss disputes between event owners and organisations they alleged were attempting to pass themselves off as associated with the event in question. The first of these involved a dispute over Olympic imagery, while the second related to alleged misuse of images belonging to the New Zealand Rugby Football Union, owners of the rugby team the All Blacks.

3.4.1 Ring Ring

In 1996, BellSouth, a recent entrant to the New Zealand telecommunications market, purchased rights to the Atlanta Olympic Games. BellSouth was thus able to promote itself as official sponsor of the New Zealand Olympic team and official supplier of mobile phones. This initiative formed part of a much larger sponsorship campaign, involving numerous sporting codes, designed to promote and facilitate BellSouth’s entry into the mobile phone market.

Dominated by a former state enterprise, Telecom New Zealand, the New Zealand telecommunications market was very competitive. Telecom had formerly held sponsorship rights to the Olympics, but had opted not to renew these at the time of the 1996 Olympic Games. Telecom also possessed an extensive sponsorship portfolio, which reflected its involvement in every sector of New Zealand telecommunications. In addition to sponsorship contracts, both companies engaged in advertising campaigns and both had highly visible retail outlets. Competition was thus fierce as the two companies fought hard either to gain or defend market share.

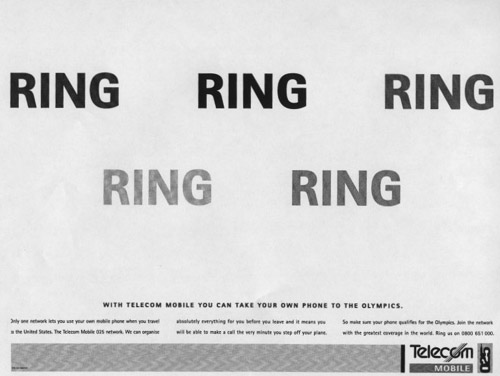

In April 1996, Telecom commenced an advertising campaign that promoted the global capacity of their mobile technology. More specifically, they noted that this technology enabled consumers to use their mobile phone, should they travel to Atlanta for the Olympic Games. To communicate this information, their advertising agency developed the advertisement shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Although shown here in black and white, the original advertisement used four-colour, and the words ‘Ring’ were each depicted in one of the Olympic colours. The advertisement, when read carefully, thus parodied the well-known interlocked ring device that is a registered image belonging to the International Olympic Committee.

Both BellSouth and the New Zealand Olympic and Commonwealth Games Association (NZO&CGA) complained strongly to Telecom after the advertisement first featured in major daily newspapers. Despite requests to cease and desist from using this advertisement, Telecom declared their intention to continue with their campaign.

Faced with this decision, the NZO&CGA sought an interim injunction that would force Telecom to halt their campaign. The basis of the NZO&CGA action was that Telecom misrepresented their status in relation to the NZO&CGA, and that the advertisement implied it was either associated with the Olympic movement or supported the New Zealand Olympic team, when neither of these interpretations was true. In addition, they claimed that the advertisement passed off Telecom as being associated with the NZO&CGA or New Zealand Olympic team. Finally, they alleged that the advertisement amounted to trademark forgery (NZO&CGA Inc. v. Telecom New Zealand Ltd, 1996 7 TCLR 167).

Because the NZO&CGA had applied for an interim injunction, evidence was limited to opinions expressed either by staff or by experts, and time constraints prevented the collection of any consumer evidence. A graphic designer argued that consumers would recognise the Olympic metaphor, and that they would associate this with Telecom. Furthermore, he argued that consumers would assume a sponsorship association simply because, as a large corporation, Telecom entered into many sponsorship arrangements.

Experts for Telecom argued that few consumers would pay the level of attention necessary either to recognise the metaphor or to interpret it as implying a sponsorship arrangement. They also claimed that sponsors normally highlighted sponsorship contracts by using terms such as ‘sponsored by’ or ‘proud sponsors of’ in advertisements and other marketing communications. Given that these terms were a regular feature of sponsorship promotions, they argued that consumers would expect to see them if the advertisement was in fact promoting a sponsorship. The absence of these terms would therefore indicate that there was no sponsorship contract between Telecom and the NZO&CGA.

In assessing the NZO&CGA’s application, McGechan J. noted several factors.[27] First, he considered the actual claims made in the advertisement. Since Telecom did not state that it sponsored the New Zealand Olympic team, and did not claim an association with the Olympic Games in general, he found that there was no evidence of a deliberate falsehood. The argument that, because Telecom sponsored many events, consumers would view the advertisement as evidence of another sponsorship association did not carry any weight.

He also considered the implications a normal reader would draw, having perused a newspaper in a typical manner. Here again, he found in favour of Telecom and noted that readers were unlikely to assume that ‘this play on the Olympic five circles must have been with the authority of the Olympic Association, or through sponsorship of the Olympics. It quite simply and patently is not the use of the five circles as such’.[28] Allegations that the advertisement amounted to trademark forgery were thus also dismissed.[29]

However, McGechan J. rejected two arguments that feature in both legal and marketing literature. First, he did not place any weight on the fact that the advertisement did not explicitly proclaim a sponsorship association. Although Telecom’s experts had argued that the absence of these claims effectively served as a disclaimer, this argument was rejected as implying a level of analysis that ‘appeals in hindsight to lawyers [but is not] the casual reality of the newspaper reader’.[30]

In rejecting this argument, McGechan J. implicitly assumed consumers process advertising rationally, and that they look for signals that guide their interpretation. This approach overlooks the more behaviourally oriented notion of respondent conditioning, where consumers become conditioned by the consistent pairing of two entities. In this case, the words "sponsored by", when consistently linked to advertising material outlining a sponsorship, create an impression that only advertisements featuring those words describe a sponsorship arrangement.[31]

Second, the judge rejected BellSouth’s claim that, should its action fail, it would be forced to review its sponsorship arrangements. In dismissing this argument, McGechan J. noted: ‘Telecom has been adventurous, perhaps unwisely so, but the Olympic Association, perhaps pushed by the competitor BellSouth, may have been perhaps a little paranoid as to possible repercussions.’[32] Although the judge did not explicitly comment on the competitive pressures that sponsors should arguably expect to encounter, this remark implies that rejection of competitors’ activities may require more thoughtful analysis. In particular, sponsors may need to consider carefully whether competitors’ actions constitute more than a mere irritation. No matter how irksome, sponsors and event owners may need to accept competitor behaviour that remains within relevant legislation. Unfortunately, the tendency for some sponsors to label as ‘ambushing’ virtually any action by a competitor that displaces attention from their sponsorship has emerged in a number of recent cases.

Courts in both the UK and New Zealand cases have recently addressed related issues. While debate has centred on the use of similar visual images, and whether these prompt consumers to make associations that do not actually exist, wider issues about the legitimate scope of competitors’ activities have also received attention. In addition, where a previous sponsorship arrangement existed, questions also arise about the extent to which a company can legitimately draw on the past to develop future promotions. The following section explores these questions in the context of the cases brought by the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) against its former sponsor Canterbury International Limited (CIL), and by the Arsenal Football Club against Matthew Reed.

3.4.2 NZRFU v. CIL

CIL supplied team jerseys to the All Blacks, New Zealand’s national rugby team, from 1918 to 1999. Over this 80-year period, the two organisations developed a considerable shared history, and the success the All Blacks enjoyed in international rugby came to be paired with CIL apparel. During the first 70 years of this relationship, the All Blacks were an amateur team. When they took on professional status, the NZRFU developed more formal sponsorship contracts and in 1985 CIL entered into a supply contract with the NZRFU that entitled them to use a silver fern mark registered to the NZRFU. This contract also contained specific supply arrangements and provisions setting out how the contract could be terminated.

As the All Black’s success continued and their international profile developed further, they became a highly attractive sponsorship proposition, and were able to command premium levels of financial support. At the same time, the costs associated with a professional team also increased greatly and sponsorship became an important revenue source. In 1999, when tenders were called for the apparel supply contract, CIL was unable to compete with the giant apparel company adidas, and the NZRFU terminated their contract with CIL and entered into an agreement with adidas.

According to the terms of the agreement CIL had with the NZRFU, they were entitled to complete production runs in progress, and they had nine months in which to sell any stock they had. At the conclusion of this period, they had no entitlement to use any of the NZRFU’s trademarks and this right was now conferred on adidas.

However, while this agreement sets out how current supply issues are to be managed, it fails to recognise the history that developed over the 80-year supply period. Instead, it assumes that the NZRFU owns All Black imagery and ignores the association that may have developed between this and CIL apparel. This may not be a critical oversight if, in fact, the NZRFU does own all the marks that had been associated with the All Blacks over the team’s history, a point the NZRFU appears to have overlooked.

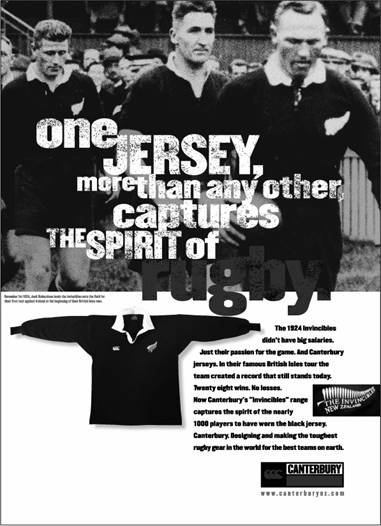

In 2001, CIL developed an advertisement that featured players from a 1924 All Black team, known as the ‘Invincibles’ because of their unbeaten record while on tour. The NZRFU alleged that this advertisement breached sections of the Fair Trading Act, which prohibits misleading or deceptive conduct, and that it misappropriated trademarks available only to official All Black sponsors. Figure 2 contains the advertisement in question.

Figure 2

As Figure 2 shows, the mark in question was not the official All Blacks logo, but a different mark, registered to a former All Black, Gary Cunningham. Although the NZRFU had initially opposed the registration of Cunningham’s mark, they had not pursued their opposition. CIL had subsequently obtained a licence from Cunningham to use his mark and argued that they were producing jerseys under the terms of that licence.

The NZRFU produced expert and in-house evidence that argued CIL’s behaviour damaged their ability to attract and retain sponsors, and created confusion in the minds of consumers. More specifically, these experts suggested that consumers would believe that CIL had produced the ‘Invincibles’ range with the NZRFU’s permission, an impression they felt would damage their relationship with adidas. The NZRFU also noted that their recent promotions, developed in conjunction with adidas, had promoted the sense of tradition associated with the All Blacks. For example, they pointed out that a current campaign featured past All Black captains putting on their All Black jerseys, a series of images designed to suggest that while the players may change, the jersey and the values it represents remain unaltered. According to the NZRFU, the CIL campaign, which also used historical images, would confuse consumers, who might believe that both CIL and adidas had sponsorship arrangements with the All Blacks.

However, the adidas ‘tradition’ campaign introduces an interesting irony. Although the advertising was designed to promote adidas’s association with the All Blacks, the jerseys shown were replicas of garments designed and produced by CIL. As a result, the campaign arguably highlights CIL’s past involvement with the All Blacks as much as it does adidas’s current sponsor status. This is turn raises the question of CIL’s entitlement to historical images, since these draw on the shared history that developed over the 80-year supply period. That is, while the supply contract can prevent use of registered marks belonging to the NZRFU, can it also prevent CIL from promoting their former involvement with the All Blacks? In addition, if CIL may use images from their past association, will this imply that their former contract is still current and lead to consumer confusion?

In his judgment, Doogue J. first considered the claims that consumers would confuse the two jerseys. He evaluated both the logos used and the overall appearance of the jerseys manufactured by CIL and adidas and concluded that the jerseys differed considerably in style. Given this, he found the likelihood that consumers would confuse the manufacturers was too low to justify granting the injunction the NZRFU sought.[33]

Justice Doogue also rejected the NZRFU’s claim to ownership of all images associated with the All Blacks, and noted that their logo device was exclusive to the NZRFU only in the specific form registered.[34] Thus, the fact that CIL had not used the NZRFU’s mark was given more weight than claims that consumers would infer the ‘Invincibles’ mark to be licensed by the NZRFU, which were unsupported by any external evidence. While the NZRFU could prevent others from unlawfully using its Silver Fern mark, its powers did not extend to cover All Black imagery in general.

Doogue J. expressly noted that CIL had a right to access images from its corporate past and that the NZRFU’s ownership of the All Blacks did not override this right. CIL’s use of the photo contained in the disputed advertisement had in fact been used since 1985, prior to the formal supply contract into which they entered with the NZRFU. The judge thus concluded: ‘In the context of the evidence before the Court, there is sufficient to establish that Canterbury must have an equal right to the images of players wearing their apparel as the NZRFU might have to images of persons who have been All Blacks.’[35]

This case has some parallels with Arsenal Football Club plc v. Matthew Reed (Chancery Division, 6 April 2001, Laddie J.).[36] In this case, Arsenal Football Club (AFC) claimed that Mr Reed, a long-standing vendor of merchandise to Arsenal supporters, misrepresented his products as official merchandise and breached trademarks belonging to the club.

In outlining their case, AFC’s counsel noted that since the early 1990s AFC had recognised the revenue opportunities available through the sale of memorabilia and had accordingly expanded their merchandising operations. AFC thus now had several large shops and an extensive mail order and web database; their overall turnover from these outlets was around £5m. At the same time as they developed their own merchandising business, which included some license arrangements, AFC became more vigilant of unlicensed traders who attempted to sell Arsenal memorabilia; evidence of actions taken to prosecute these traders was provided. AFC also sought to educate their fans that not all suppliers offered official Arsenal merchandise by including information in programmes and other material fans received, and by clearly marking their own products as ‘official’.

Because of the similarity in the material sold by Mr Reed and available from AFC or its licensees, AFC argued that many consumers would believe that Mr Reed’s goods were either produced by AFC or licensed by the club. In response, Mr Reed’s counsel argued that most fans only wanted to indicate their support for Arsenal and had little interest in the authenticity of the merchandise. Furthermore, he suggested that those fans who wished to obtain authentic merchandise would not be confused.

Laddie J. concluded that, since Mr Reed had retailed his products for several years, evidence of confusion, if it existed, would be easily found. As he noted: ‘Absences of evidence of confusion become more telling and more demanding of explanation by the claimant the longer, more open and more extensive the defendant’s activities are’ [para 24, judgment, Case HC1999 - 0038]. Since no evidence of confusion was presented, Laddie J. concluded that AFC had not established their case. He also commented that, given AFC’s efforts to differentiate ‘official’ merchandise from other products, the likelihood of confusion occurring was further reduced. In addition, Laddie J. noted that Mr Reed went to some trouble to ensure potential consumers knew which of his goods were officially sanctioned and which were not (cf. NHL v. Pepsi 92 DLR.4th 349). Overall, this led him to conclude that: ‘I find it difficult to believe that any significant number of customers wanting to purchase licensed food could reasonably think that Mr Reed was selling them, save when they are so expressly marked’. [para 41, judgment, Case HC1999–0038]. AFC had also claimed that Mr Reed had deceptively used the word ‘official’ when he was not entitled to do so. However, Laddie J. did not accept the evidence provided, and both passing off claims failed.

In defence of the second cause of action, the misuse of trademark claim, Mr Reed argued that he was not using the devices featured on his goods to indicate the origin of those goods, but as badges of allegiance to the club. Laddie J. accepted that the devices were being used in a non-trademark manner, although the wider question of whether non-trademark use could infringe a registered mark has wide-ranging implications and so has been referred to the European Court of Justice.

These cases imply that event owners and official sponsors need to register all marks associated with their team or event as soon as these are developed. Failure to do so leaves open the opportunity for others to use the devices, and to develop their own goodwill in connection with these. Doogue J.’s judgment made it clear that, at least in the case of long-standing sponsorship contracts, sponsors may continue to have rights to images created during the sponsorship even after this has terminated. It is not yet clear whether contracts containing more explicit exit rights will be able to close this loophole.

4. Remedies Open to Sponsors and Event Owners

The above sections suggest that a range of activities referred to by marketers as ‘ambushing’ do not necessarily breach fair-trading, trademark or passing off legislation. Instead of classifying all competing promotions as ambushing, it is more logical to think of a continuum, anchored by legitimate competition at one end and actionable behaviour at the other. The difficulty is not in identifying anchor points, but in determining whether activities falling between these are liable. The remainder of this section examines how this latter question could be ascertained.

Remedies are available to event owners and sponsors where a company’s behaviour has breached relevant legislation. As the cases above suggest, this implies that the behaviour must involve misappropriation of trademarks, passing off or other behaviour that creates consumer confusion. It does not extend to cover normal competitive behaviour, such as the implementation of simultaneous promotions (unless the content of these breaches trade practice legislation).

As the cases outlined above illustrate, claims that a competitor has breached relevant statutes require specific evidence, particularly of consumer confusion, for an action to succeed. For example, evidence that consumers mistakenly associated Telecom with the New Zealand Olympic team, or that Arsenal fans mistakenly thought Mr Reed was licensed to sell official Arsenal merchandise, could amount to proof that confusion existed. Yet studies into the effects of alleged ambushing on consumers suggests that this research requires careful assessment before it is accepted.

Sandler and Shani first examined the effects of alleged ambushing on consumers following the 1988 Olympic Games.[37] Overall, they found that a larger proportion of respondents to a survey recognised and correctly linked official sponsors to an event than they did alleged ambushers, or other competitors in their product category. Yet their specific results suggested that consumers’ ability to recognise the official sponsors varied considerably according to the product category examined.[38]

More recently, researchers have examined the relationship between brand usage and sponsorship attribution. Quester, Farrelley and Burton suggested that consumers who do not recognise the official sponsor of an event often name a brand they use as the sponsor.[39] The net effect of this is that brands with high penetration tend to be linked to sponsorship, even when they have not invested in a team or event. However, Quester et al.’s research suggests that this association depends not on marketing activity or alleged ambushing, but on consumers’ past purchase behaviour.[40] Evidence of misassociation thus needs to be considered carefully in the light of respondents’ purchase behaviour and the overall market structure.

From a behavioural point of view, this research suggests that while event owners and official sponsors may find the actions of some competitors irritating, they could have difficulty in identifying whether and how the behaviour affected consumers. From a legal perspective, this finding means that ‘ambush marketing’ is no different from any other behaviour that allegedly creates confusion and that requires material evidence of that confusion to succeed.[41]

Although cases involving trademark disputes or other allegedly deceptive behaviour have used survey evidence to illustrate consumer confusion (or lack thereof), survey research has not always withstood detailed cross-examination.[42] Event owners thus need to clarify the legal status of their complaint, as well as considering how they can provide external evidence in support of their action. While Whitford J. has identified several criteria that surveys should meet, the status accorded to survey evidence remains rather variable, and too few practitioners recognise the higher standards required of court-adduced surveys.[43]

Tighter sponsorship contracts that define sponsors’ rights and event owners’ responsibilities may provide more grounds for action and a greater range of remedies. This suggestion implies that event owners will take on greater responsibility for the benefits sponsors hope to achieve, an obligation they may not wish to shoulder. While the IOC has moved to protect the rights of sponsors, and has, at least at the Sydney 2000 Games, vigorously monitored actions that might affect these, other event owners have yet to demonstrate the same vigilance. Until the benefits for event owners and sponsors are mutually dependent, there may be little incentive for event owners to curtail the range of sponsorships currently available or defend the rights of official sponsors.

McGechan J. suggested that a change in legislation may be required to extend the protection currently afforded to images that belong to major sporting bodies, such as the International Olympic Committee. Such legislation could extend protection beyond the visual marks themselves, and so might eventually cover disputes involving ‘image-by-association’, such as the Ring Ring case. Thus, while sporting bodies may be exerting pressure on legislators to make these changes, current trademark legislation has not yet been revised in this way.

As well as examining external forms of protection, event owners and marketers could do more to strengthen their own stance. The present cry of ‘ambush marketing’ in response to virtually any kind of competitive behaviour confuses ethical opinions with what are ultimately legal issues. Marketers would do well to seek to clarify the legal status of their complaint, since only this will identify the remedies open to them and the steps they must take to pursue these. Having clarified their legal options, marketers should also consider carefully the evidence they require to establish their case, and ensure that this is collected in a manner that will withstand critical scrutiny.

5. Conclusions

Competitors who detract from sponsorship can irritate their rivals, especially if the promotion in question required considerable investment. Particularly innovative campaigns can not only detract from the sponsorship but, through creative use of similar images, may even confuse consumers about the official sponsor.

However, labelling these promotions as ‘ambushing’ does not help clarify either the actions that have occurred or the remedies available to the aggrieved parties. The response from event owners and sponsors risks confusing the legal status of competitors’ behaviour with the emotions that behaviour evokes. ‘Ambushing’ has no legal referent and marketers need to explore the legal remedies available to them when competitors engage in provocative or misleading behaviour.

In particular, they need to consider whether competitors have explicitly or implicitly misappropriated their trademarks, and how they could establish the effects of this behaviour. Similarly, if their competitors’ promotions may mislead of deceive consumers, marketers need to provide robust evidence of any confusion; this will only be possible if they focus on the courts’ requirements.

In summary, ambush marketing will only ever be a commercial irritant because it has no status outside of marketing jargon. By contrast, passing off, misappropriation of trademarks, breaches of contract, and infringement of fair-trading statutes could provide the basis for action. Marketers and event owners would be well advised to concentrate on the legal issues raised by a competitor’s behaviour and avoid self-referential marketing terms lest these create further confusion.

NOTES

1 See J. Hoek, ‘Sponsorship: An Evaluation of Management Assumptions and Practices’, Marketing Bulletin 10/? (1999), 1–10, for a more detailed discussion of these points.

2 The following papers provide a more in depth analysis of this point: K. Parker, ‘Sponsorship: The Research Contribution’, European Journal of Marketing 25/11 (1991), 22–30; D. Scott and H. Suchard, ‘Motivations for Australian Expenditure On Sponsorship’, International Journal of Advertising 11/? (1992), 325–32; and J. Crimmins and M. Horn, ‘Sponsorship: From Management Ego Trip To Marketing Success’, Journal of Advertising Research 36/? (1996), 11–21.

3 Hoek (note 1). See also D. Sandler, ‘Sponsorship and the Olympic Games: The Consumer Perspective’, Sport Marketing Quarterly 2/3 (1993), 38–43.

4 T. Altobelli, ‘Cashing in on the Sydney Olympics’, Law Society Journal 35/4 (1997), 44–6.

5 L. Bean, ‘Ambush Marketing: Sports Sponsorship Confusion and the Lanham Act’, journal name? 75/? (September 1995), 1099–1134; D. Shani and D. Sandler, ‘Ambush Marketing: Is Confusion to Blame for the Flickering of the Flame?’, Psychology and Marketing 15/4 (1998), 367–83.

6 D. Sandler and D. Shani, ‘Olympic Sponsorship vs “Ambush” Marketing: Who Gets the Gold?’, Journal of Advertising Research 29/? (1989), 9–14.

7 T. Meenaghan, ‘Point Of View: Ambush Marketing – Immoral Or Imaginative Practice?’, Journal of Advertising Research 34/ 3 (1994), 77–88; Shani and Sandler (note 5).

8 Meenaghan (note 7); T. Meenaghan, ‘Ambush Marketing – A Threat To Corporate Sponsorship’, Sloan Management Review 38/? (1996), 103–13; Sandler and Shani (note 6).

9 T. Meenaghan, ‘Ambush Marketing: Corporate Strategy and Consumers’ Reactions’, Psychology and Marketing 15/4 (1998), 305–22, at 306.

10 Meenaghan (note 7); M. Payne, ‘Ambush Marketing: The Undeserved Advantage’, Psychology and Marketing 15/4 (1998), 323–31.

11 J. Tripoldi and M. Sutherland, ‘Ambush Marketing An Olympic Event’, Journal of Brand Management 7/6 (2000), 412–22; Sandler and Shani (note 6); P. O’Sullivan and P. Murphy, ‘Ambush Marketing: The Ethical Issues’, Psychology and Marketing 15/4 (1998), 349–66.

12 Sandler and Shani (note 6); O’Sullivan and Murphy (note 11).

13 Meenaghan (note 9); P. Graham, ‘Ambush Marketing’, Sport Marketing Quarterly 6/1 (1997), 10–12; Payne (note 10).

14 Meenaghan (note 9).

15 Bean (note 5).

16 Meenaghan (note 9).

17 T. Meenaghan, ‘Current Developments and Future Directions in Sponsorship’, International Journal of Advertising 17/1 (1998), 3–28.

18 Graham (note 13), 10, 12.

19 See Meenaghan (note 9).

20 Graham (note 13); see also Shani and Sandler (note 5).

21 Bean (note 5).

22 Shani and Sandler (note 5).

23 M. Roper-Drimrie, ‘Sydney 200 Olympic Games – “The Worst Games Ever” For Ambush Marketers?’, Entertainment Law Review 5/? (2001), 150–3.

24 Bean (note 5).

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 NZO&CGA Inc. v. Telecom New Zealand Ltd [1996] 7 TCLR 167.

28 Ibid.

29 See J. Hoek, ‘Ring Ring: Visual Pun or Passing Off?’, Asia-Australia Marketing Journal 5/? (1997), 33–44, for more detailed discussion of the decision.

30 NZO&CGA Inc. v. Telecom New Zealand Ltd [1996] 7 TCLR 167.

31 P. Nord and J. Peter, ‘A Behaviour Modification Perspective on Marketing’, Journal of Marketing 44/? (1980), 36–47.

32 NZO&CGA Inc. v. Telecom New Zealand Ltd [1996] 7 TCLR 167.

33 New Zealand Rugby Football Union v. Canterbury International Limited, 10 July 2001, unreported judgment CP167/01.

34 See J. Hoek and P. Gendall, ‘When Do Ex-Sponsors Become Ambush Marketers?’, International Journal Of Sports Marketing And Sponsorship 3/4 (year?), 383–402, for a more detailed discussion of this case.

35 New Zealand Rugby Football Union v. Canterbury International Limited, 10 July 2001, unreported judgment CP167/01.

36 Arsenal Football Club v. Matthew Reed LTL 6/4/2001; TLR 26/4/2001; [2001] IPD 24037; [2001] 2 CAR 922.

37 Sandler and Shani (note 5).

38 See S. McDaniel and L. Kinney, ‘Ambush Marketing Revisited: An Experimental Study of Perceived Sponsorship Effects on Brand Awareness, Attitude toward the Brand and Purchase Intention’, Journal of Promotion Management 3/1–2 (1993), 141–67.

39 P. Quester, F. Farrelly and R. Burton, ‘Sports Sponsorship Management; A Multinational Comparative Study’, Journal of Marketing Communications 4/? (1998), 115–28.

40 Quester et al. (note 39).

41 S. Townley, D. Harrington and N. Couchman, ‘The Legal and Practical Prevention of Ambush Marketing in Sports’, Psychology and Marketing 15/4 (1998), 333–48.

42 I. Preston, ‘The Scandalous Record of Avoidable Errors in Expert Evidence Offered in FTC and Lanham Act Deceptiveness Cases’, Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 11/2 (1992), 57–67, provides a comprehensive overview of survey research used in court.

43 J. Skinnon and J. McDermott, ‘Market surveys as evidence: Courts still finding fault’, Australian Business Law Review 26/? (1998), 435–49, provide a more recent overview of this topic.