Planetary shields will buckle under stellar winds from their dying stars

Any life identified on planets orbiting white dwarf stars almost certainly evolved after the star’s death, says a new study led by the University of Warwick that reveals the consequences of the intense and furious stellar winds that will batter a planet as its star is dying.

Any life identified on planets orbiting white dwarf stars almost certainly evolved after the star’s death, says a new study led by the University of Warwick that reveals the consequences of the intense and furious stellar winds that will batter a planet as its star is dying.

The research is published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, and lead author Dr Dimitri Veras of the University of Warwick will present it today (21 July) at the online National Astronomy Meeting (NAM 2021).

The research provides new insight for astronomers searching for signs of life around these dead stars by examining the impact that their winds will have on orbiting planets during the star's transition to the white dwarf stage. The study concludes that it is nearly impossible for life to survive cataclysmic stellar evolution unless the planet has an intensely strong magnetic field – or magnetosphere - that can shield it from the worst effects.

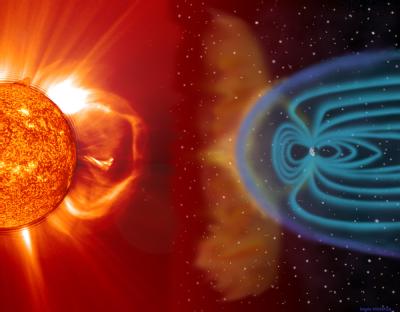

In the case of Earth, solar wind particles can erode the protective layers of the atmosphere that shield humans from harmful ultraviolet radiation. The terrestrial magnetosphere acts like a shield to divert those particles away through its magnetic field. Not all planets have a magnetosphere, but Earth’s is generated by its iron core, which rotates like a dynamo to create its magnetic field.

All stars eventually run out of available hydrogen that fuels the nuclear fusion in their cores. In the Sun the core will then contract and heat up, driving an enormous expansion of the outer atmosphere of the star into a ‘red giant’. The Sun will then stretch to a diameter of tens of millions of kilometres, swallowing the inner planets, possibly including the Earth. At the same time the loss of mass in the star means it has a weaker gravitational pull, so the remaining planets move further away.

During the red giant phase, the solar wind will be far stronger than today, and it will fluctuate dramatically. Veras and Vidotto modelled the winds from 11 different types of stars, with masses ranging from one to seven times the mass of our Sun.

Their model demonstrated how the density and speed of the stellar wind, combined with an expanding planetary orbit, conspires to alternatively shrink and expand the magnetosphere of a planet over time. For any planet to maintain its magnetosphere throughout all stages of stellar evolution, its magnetic field needs to be at least one hundred times stronger than Jupiter’s current magnetic field.

The process of stellar evolution also results in a shift in a star’s habitable zone, which is the distance that would allow a planet to be the right temperature to support liquid water. In our solar system, the habitable zone would move from about 150 million km from the Sun – where Earth is currently positioned – up to 6 billion km, or beyond Neptune. Although an orbiting planet would also change position during the giant branch phases, the scientists found that the habitable zone moves outward more quickly than the planet, posing additional challenges to any existing life hoping to survive the process.

Eventually the red giant sheds its entire outer atmosphere, leaving behind the dense hot white dwarf remnant. These do not emit stellar winds, so once the star reaches this stage the danger to surviving planets has passed.

Dr Dimitri Veras of the University of Warwick Department of Physics said: “This study demonstrates the difficulty of a planet maintaining its protective magnetosphere throughout the entirety of the giant branch phases of stellar evolution."

“One conclusion is that life on a planet in the habitable zone around a white dwarf would almost certainly develop during the white dwarf phase unless that life was able to withstand multiple extreme and sudden changes in its environment."

“We know that the solar wind in the past eroded the Martian atmosphere, which, unlike Earth, does not have a large-scale magnetosphere. What we were not expecting to find is that the solar wind in the future could be as damaging even to those planets that are protected by a magnetic field”, says Dr Aline Vidotto of Trinity College Dublin, the co-author of the study.

Future missions like the James Webb Space Telescope due to be launched later this year should reveal more about planets that orbit white dwarf stars, including whether planets within their habitable zones show biomarkers that indicate the presence of life, so the study provides valuable context to any potential discoveries.

So far no terrestrial planet that could support life around a white dwarf has been found, but two known gas giants are close enough to their star’s habitable zone to suggest that such a planet could exist. These planets likely moved in closer to the white dwarf as a result of interactions with other planets further out.

Dr Veras adds: “These examples show that giant planets can approach very close to the habitable zone. The habitable zone for a white dwarf is very close to the star because they emit much less light than a Sun-like star. However, white dwarfs are also very steady stars as they have no winds. A planet that’s parked in the white dwarf habitable zone could remain there for billions of years, allowing time for life to develop provided that the conditions are suitable.”

Ends

Notes to editors:

Image and caption

An illustration of material being ejected from the Sun (left) interacting with the magnetosphere of the Earth (right). When the Sun evolves to become a red giant star, the Earth may be swallowed by our star's atmosphere, and with a much more unstable solar wind, even the resilient and protective magnetospheres of the giant outer planets may be stripped away. Credit: MSFC / NASA

Further information

The new research appears in “Planetary magnetosphere evolution around post-main-sequence stars”, Veras D. and Vidotto A., Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, in press.

About the Royal Astronomical Society

The Royal Astronomical Society (RAS), founded in 1820, encourages and promotes the study of astronomy, solar-system science, geophysics and closely related branches of science. The RAS organises scientific meetings, publishes international research and review journals, recognizes outstanding achievements by the award of medals and prizes, maintains an extensive library, supports education through grants and outreach activities and represents UK astronomy nationally and internationally. Its more than 4,000 members (Fellows), a third based overseas, include scientific researchers in universities, observatories and laboratories as well as historians of astronomy and others.

Follow the RAS on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and YouTube

Download the RAS Supermassive podcast

About the Science and Technology Facilities Council

The Science and Technology Facilities Council is part of UK Research and Innovation – the UK body which works in partnership with universities, research organisations, businesses, charities, and government to create the best possible environment for research and innovation to flourish. STFC funds and supports research in particle and nuclear physics, astronomy, gravitational research and astrophysics, and space science and also operates a network of five national laboratories as well as supporting UK research at a number of international research facilities including CERN, FERMILAB and the ESO telescopes in Chile. STFC is keeping the UK at the forefront of international science and has a broad science portfolio and works with the academic and industrial communities to share its expertise in materials science, space and ground-based astronomy technologies, laser science, microelectronics, wafer scale manufacturing, particle and nuclear physics, alternative energy production, radio communications and radar.

STFC's Astronomy and Space Science programme provides support for a wide range of facilities, research groups and individuals in order to investigate some of the highest priority questions in astrophysics, cosmology and solar system science. STFC's astronomy and space science programme is delivered through grant funding for research activities, and also through support of technical activities at STFC's UK Astronomy Technology Centre and RAL Space at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory. STFC also supports UK astronomy through the international European Southern Observatory.

Follow STFC on Twitter

About the University of Bath

The University of Bath is one of the UK's leading universities both in terms of research and our reputation for excellence in teaching, learning and graduate prospects.

The University is rated Gold in the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), the Government’s assessment of teaching quality in universities, meaning its teaching is of the highest quality in the UK.

In the Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2014 research assessment 87 per cent of our research was defined as ‘world-leading’ or ‘internationally excellent’. From developing fuel efficient cars of the future, to identifying infectious diseases more quickly, or working to improve the lives of female farmers in West Africa, research from Bath is making a difference around the world. Find out more

Well established as a nurturing environment for enterprising minds, Bath is ranked highly in all national league tables. We are ranked 6th in the UK by The Guardian University Guide 2021, and 9th in The Times & Sunday Times Good University Guide 2021 and 10th in the Complete University Guide 2021. Our sports offering was rated as being in the world’s top 10 in the QS World University Rankings by Subject in 2021.

21 July 2021

University of Warwick press office contact:

Peter Thorley

Media Relations Manager (Warwick Medical School and Department of Physics) | Press & Media Relations | University of Warwick

Email: peter.thorley@warwick.ac.uk

Mob: +44 (0) 7824 540863