Which COVID-19 models should we use to make policy decisions?

- With so many COVID-19 models being developed, how do policymakers know which ones to use? A new process to harness multiple disease models for outbreak management has been developed by an international team of researchers including the University of Warwick.

- They propose separate modeling groups formally discuss their models with each other, to examine why their models might disagree. The groups work independently again to refine their models, based on the insights from the discussion and comparison stage.

- After group discussion and individual model refinement, the models are combined into an overall projection for each management strategy, which can be used to help guide risk analysis and policy deliberation.

An International group of researchers, including the University of Warwick, have developed a new process to harness multiple disease models for outbreak management, meaning public health agencies can understand the merits of different management options in testing times such as these currently experienced with Covid-19.

During a disease outbreak, many research groups independently generate models, for example projecting how the  disease will spread, which groups will be impacted most severely, or how implementing a particular management action might affect these dynamics. These models help inform public health policy for managing the outbreak.

disease will spread, which groups will be impacted most severely, or how implementing a particular management action might affect these dynamics. These models help inform public health policy for managing the outbreak.

“While most models have strong scientific underpinnings, they often differ greatly in their projections and policy recommendation,” said lead author Katriona Shea, professor of biology and Alumni Professor in the Biological Sciences, Penn State. “This means that policymakers are forced to rely on consensus when it appears, or on a single trusted source of advice, without confidence that their decisions will be the best possible.”

At the onset of an outbreak, a large amount of information is often unavailable or unknown, and researchers must make decisions about how to incorporate this uncertainty into their models, leading to differing projections.

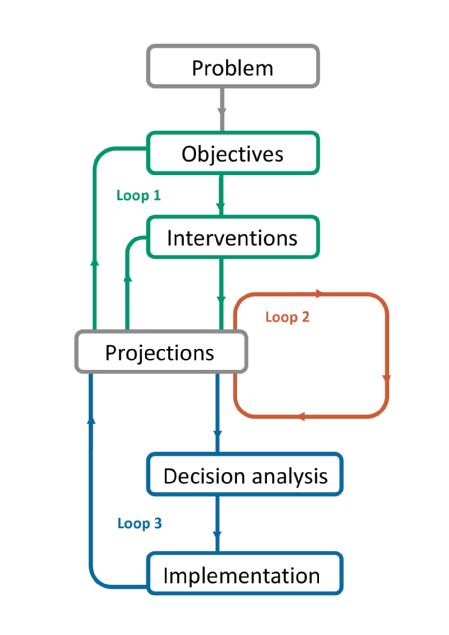

In the paper, ‘Harnessing multiple models for outbreak management’ published in the journal Science, researchers propose a three-part process as follows:

1. Multiple research groups first create models for specified management scenarios independently, to encourage a wide range of ideas without prematurely conforming to a certain way of thinking.

2. The modeling groups formally discuss their models with each other—an important addition to previous multiple model methods—which allows them to examine why their models might disagree.3. Finally, the groups work independently again to refine their models, based on the insights from the discussion and comparison stage.

After group discussion and individual model refinement, the models are combined into an overall projection for eac h management strategy, which can be used to help guide risk analysis and policy deliberation. At this stage, methods from the field of decision analysis can allow the decision maker, for example a public health agency, to understand the merits of different management options in the face of the existing uncertainty.

h management strategy, which can be used to help guide risk analysis and policy deliberation. At this stage, methods from the field of decision analysis can allow the decision maker, for example a public health agency, to understand the merits of different management options in the face of the existing uncertainty.

The combined results can also help identify which uncertainty - what pieces of missing information - are most critical to learn about in order to improve models and thus improve decision making, providing a way to prioritise research directions.

Researchers plan to implement this process immediately for COVID-19, by taking advantage of the many research groups already producing models for the current outbreak, the strategy should be easy to implement while producing more robust results from the existing process.

Dr Mike Tildesley, from the School of Life Sciences at the University of Warwick comments: “Even after initial decisions are made, the process can continue as new information about the outbreak and management becomes available. This ‘adaptive management’ strategy can allow researchers to refine their models and make new predictions as the outbreak progresses.

“For COVID-19, this process might inform how and when isolation and travel bans are lifted, and if these or other measures might be necessary again in the future.”

Professor Shea adds: “This method can provide a framework for future outbreak settings, including emerging diseases and agricultural pest species, and management of endemic infectious diseases, including vaccination strategies and disease surveillance.”

ENDS

7 MAY 2020

NOTES TO EDITORS

Images available at:

https://warwick.ac.uk/services/communications/medialibrary/images/april2020/shea_2020_figure1.jpg

Simplified Diagram:

A new process to evaluate multiple disease outbreak models will help inform public health policy decisions for managing the outbreak. The process is currently being applied to the current COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Will Probert, University of Oxford

https://warwick.ac.uk/services/communications/medialibrary/images/april2020/1.jpg

University ID card scanning:

A new process to evaluate multiple disease models will help identify which intervention measures may be most successful during an outbreak. Shown here, the entry process for students at Lanzhou University in China involves scanning a university ID, which is associated with the student’s body temperature history, travel history, and other information, while a machine detects current body temperature. Credit: Shouli Li, Lanzhou University

Release to publish at: https://science.psu.edu/news/Shea5-2020

DOI: 10.1126/science.abb9934

In addition to Shea and Tildesley, the research team includes Michael Runge a research ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, David Pannell at the University of Western Australia, William Probert at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, Shou-Li Li at Lanzhou University in China and Matthew Ferrari at Penn State.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the Penn State Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences though the Coronavirus Research Seed Fund.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT:

Alice Scott

Media Relations Manager – Science

University of Warwick

Tel: +44 (0) 7920 531 221

E-mail: alice.j.scott@warwick.ac.uk

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION PLEASE CONTACT:

Alice Scott

Media Relations Manager – Science

University of Warwick

Tel: +44 (0) 7920 531 221

E-mail: alice.j.scott@warwick.ac.uk