Dispatches from the Global Pandemic

We have asked our project partners and colleagues to send us their dispatches from the lockdown. What follows are political and personal reflection from Brazil, India and Spain.

Muslims as contagion: The image of “terrorists” carrying COVID-19 in India[1]

Brahma Prakash

In the background of the pandemic COVID 19, there has been an attempt to target Muslim communities in India. The Indian government under the leadership of Modi was on backfoot during the anti-CAA-NRC protest. It used the COVID 19, to turn public opinion around and cleanse the protest sites and demonize the community. If we believe our government and media, the most dreaded terrorists in India do not carry grenades, rocket launchers or AK-47s. They carry COVID-19. The bio-terrorists are producing contagion to eliminate the Hindus. In place of exploding grenades, the new "terrorists" sputter coronavirus. The unfortunate congregation of Tabligi Jamaat in Delhi is being viewed as a conspiracy, an act of "treason", and a case of "Islamic insurrection".

Islamophobia in India is proliferating along with the pandemic. It is branding all Indian Muslims as terrorists and the source of all the evils. The emerging violence can be seen as an analogy in which Hindus are seen as sacred contagion and Muslims as dangerous contagion. While the sacred contagion has every right to spread, the dangerous contagion has to be contained. It can be also seen as an attempt to impose a Hindu social order on Muslim communities, wherein they become "terrorists" by birth, as one becomes a Brahmin or an "untouchable", or as nomads become born "criminals", and members of performing communities born "prostitutes". COVID 19 in India is also about containing and quarantining Muslims, who could not be contained during the anti-CAA-NRC protests. It is also about containing the misapprehended Muslims who represent a world of chaos for the Hindus.

Writing on the plague, French critic Rene Girard says, "the distinctiveness of the plague is that it ultimately destroys all forms of distinctiveness".[2] But an epidemic has never been that equalizer. Rather, it brings discrimination and stigmatization against its perceived "enemy". In the case of COVID 19, Americans are blaming immigrant Chinese; Chinese are blaming Uyghurs, Pakistan is blaming Hazara minority, India is blaming Muslims, and Muslims are blaming their jahil Muslims for spreading the virus. By blaming Muslims, the Indian state and media are shifting focus from narratives in which upper-classes (who fly and travel abroad) were considered as the carriers of the disease. It was important to shift focus as it was against the narratology of the nation and the corporate media.

There seems to be a simmering connection between physical and ideological contagion. If the coronavirus is a bodily contagion, Muslims are projected as another dangerous contagion. When both are merged, it creates a ripple effect. While the disease becomes an evil, the community itself is considered "diseased". The state invoking the NSA (National Security Act) against the members of the Jamaat, who themselves are victims of COVID-19, is no longer a surprise. From "Love Jihad" to "Corona Jihad", Islamophobia has many names in India. The prevailing situation in India also proves that islamophobia is becoming too mild term to encompass the nature of the violence. It is taking the form of apartheid. This is quite similar to what BR Ambedkar has described as "permanent segregation" in the case of "untouchables"

The notion of Muslims as a dangerous contagion cannot be separated from the Hindus as a "sacred contagion". Hinduism as a sacred contagion has the right to spread anywhere. One who comes in contact with it becomes pure. The truth is that even the pandemic could not escape the endemic of the Hindu social order. There is a possibility that the pandemic will consolidate the Hindu social order further. In the Hindu social order, if Dalits are dirt, Muslims are infections. The image of Muslims as infections goes well with the spread of the coronavirus.

Recently, Modi said that democratic “citizenry” are “manifestations of God”. Therefore, anything that harms citizens must be a manifestation of evil. From secular notions, as per those enshrined in the Indian Constitution, Indian citizenship has now acquired religious meanings. Democratic institutions, from the Legislative to the Judiciary have become part of the sacred. It is the sacred contagion of Hinduism that holds the centre and it is a mythical archetype in which security assumes the notion of sacredness and health becomes an affliction of “evil forces”. It is the premonition of a mythical society that is fighting a “divine war” against the COVID-19.

India’s fight against the COVID-19 is not only about containing the virus, but also about “containing” the country’s Muslims forever. It is not surprising that sedition charges and arrests of Muslim activists have taken place in parallel with the war against the pandemic. Also, the anxieties and failures to contain COVID-19 have resulted in increased anger and hatred towards Muslims. The formula is clear: if you cannot contain COVID-19, “contain” Muslims — a fight that is far more profitable than the fight against coronavirus.

[1] This is a short version of the article published in Indian Cultural Forum on 23 April 2020. https://indianculturalforum.in/2020/04/23/muslims-as-contagion-the-image-of-terrorists-carrying-covid-19-in-india/

[2] Girard, René. "The plague in literature and myth." Texas Studies in Literature and Language 15, no. 5 (1974): 833-850., p. 834.

The Pandemic and exploring New Performance Strategies

(of the Left oriented organizations)

Komita Dhanda

Amidst the lockdown due to Covid19, when the physical gathering has become impossible, many artists-activists of the left in India have turned towards the social media platforms in the hope of remaining connected to the audiences and group members. Consequently, in last two months, we have seen a gamut of online performances, workshops, recitations and webinars being organized by various artists and theatre practitioners.

Speaking on behalf of the Left theatre group, Jana Natya Manch (Janam) of which I am a long term member, spring 2020 was a challenging time. Like everyone else we tried to make sense of the situation. As we wanted to continue with our cultural work, the online platforms seemed an option, thus we decided to experiment with the virtual medium.

Perform From Home

Everybody can see that the king is naked

but everybody keeps clapping away.

Everybody shouts: bravo, bravo.

some are trapped in misbeliefs, some in fear

yet others have mortgaged their brains…

On the occasion of the 150th birth anniversary of Lenin, this year, Moloyashree Hashmi, a member of our group (Janam), read the Hindi translation of Ulongo Raja (The King is Naked) written by famous Bengali poet Nirendranath Chakraborty, on Facebook Live. As we witnessed images of Indian workers migrating back to their hometowns in the dearth of livelihood, food, and health care, the poem, as opposed to the gimmicky announcements by the Indian Prime Minister appeared more relevant than ever. During the lockdown, besides organizing online events, a number of the left cultural activists have been involved with the workers’ unions for raising funds, running community kitchens and distributing ration.

We curated a six-hour-long online poetry recitation of radical and revolutionary poems from across the world to commemorate Lenin’s birthday. Each recitation started with an appeal for contributions towards ongoing relief work efforts for the workers. A week earlier Janam members had read poems on Instagram to mark the birth anniversary of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. Over the next few days, more than five thousand viewers watched our poetry videos on Facebook.

In another attempt, on 12 April, to observe the National Street Theatre Day, we read one of our older street plays. A few rehearsal sessions helped the actors to get a hang of the medium and technology. Keeping their scripts in front, actors picked up the cues and said their lines. The first few performances were received fairly well by the audience. As we went along many of the former members of the groups joined us online for these readings and recitations. While reading the lines, we however could feel the urge of our bodies to move – to perform the gestures which illustrate the words and it was a struggle to not use the body and try to infuse the same energy in the enunciations of the lines. This was a reversal of techniques used in agit props.

For us, May Day is an important event in Janam. We attend workers’ rally every year in Delhi. On the eve of May Day this year, we did live reading of poems on labour and work. Our comrades of a small left-wing publication, LeftWord Books do a daylong annual event, amidst books sale, coffee, and a series of performances, poetry, and music. This year the event was organized on an open-source live stream platform bringing together a number of Indian and international poets, artists, and musicians from all over the world. Roger Waters sang for us, while the subversive comedy trio, Aisi Taisi Democracy (loosely translated as Democracy, Messed Up) spoke of COVID, the Indian State, and the spread of unscientific belief system among people. Singer Pallavi M.D. from India sang folk compositions on caste and gender, a Brazilian feminist group As Cantadeires presented songs of resistance, young poet Amir Raza from Mumbai recited powerful radical poetry. Over six thousand viewers watched this eleven-hour long cultural celebration of May Day.

Through online platforms, we are exploring a new audience base but a large part of our spectatorship is working-class who either has limited or no access to the Internet or the device that allows one to use the technology. When any public assembly or gathering seems uncertain, we need to think of new strategies for our cultural work in the post-Corona world.

Till then, physical distance, social solidarity.

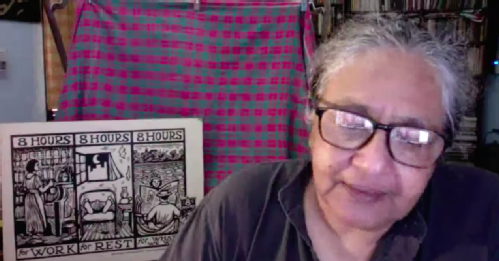

In the photo: Moloyashree Hashmi

PM CARES[i]…for All.

Do they care about cultural workers too?

Aastha Gandhi

India is possibly entering Phase 4 of the Covid-19 lockdown. Despite being under these restricted conditions for over 50 days, the number of infected cases continues to be on the rise. Without a source of income, millions of daily wagers have been forced to fend for themselves and have resorted to retreating from the cities to which they had migrated. Images of labourers walking across the country are strewn across the news channels, and social media. As the lockdown extended time and again over the past few weeks, their plight has only grown more tumultuous.

The neoliberal project of the nation-state and its infrastructural expansion willingly welcomes and requires cheap and surplus labour force. We have witnessed that with the outburst of the pandemic, this movement is reversed, as the marginalized migrant labour are the first ones to be ousted as unwanted, undesired burden of a neoliberal dream. In this dispatch, I briefly look at the role of the artistes in these times of crises. Do they make work responding to the crisis and try to voice the desperate plight of the migrant, unemployed, homeless labourers? What are the areas where art can contribute: the migrant crisis, the health crisis or the mental health of those stuck inside their homes?

Do these art practices through choosing the plight of the migrants workers as the subject of their works, actually antagonize the state? Is there a political position for artistes who are making art work in digital formats and circulating?

Dilli kiski hoti hai (Who does Delhi belong to?), a short film created as part of Quarantine Video Project by Odddbird Theatre & Foundation in Delhi, brings the plight of these migrant labour to the fore and raises a crucial question whether they are ever completely accepted by the city.[ii] The issue has found resonance with other performance work as well.[iii]

Over the past few weeks, some of the art organizations have come forward in support of providing a platform for newer creations when physical performance spaces have been replaced by virtual ones. I particularly mention here Lois Weaver’s Care Café as trying to create a safe space for strangers to talk and be heard online on current relevant issues.[iv] Though the contexts are different, maybe there is an immediate need to provide a space for care, for artists and also by artists for their audiences. This leads us to re-think about the digital platform too. Is it a choice the artiste is making or a compulsion? Even if there is a desperate need to reach out to the audience, what are the tools and methods that performers can rely on while sitting at home?

Maya Rao’s work stands out in this context. Physical theatre, dance, and voice are the core forms she uses for her performances. However, now she has shifted to using only her voice and few images to create three minute long acts, in a series centred around the character of a middle-class woman, called “Paru”. In this particular episode titled “I CARE”, a direct pun on “PM CARES”, she subverts the text and plays with the often used jargon of an apathetic government.[v]

The government engrossed in recovering the global neo-liberal economy and bring back the status quo, will rarely accommodate what we read as meaningful performance practices. Although, we have seen in recent past that few developed nation-states have dispersed funds to their artists, for most part, the artists in developing countries find themselves without any means of survival. The cultural practices which were always subsidized by the state are no more a priority. The fundamental question that occupies a neo-liberal government is the restoration of the economy, and to make a choice between economic revival and the health of a huge population at stake. So what remains the place for art and cultural practices in such regimes? Arundhati Roy defines this as a state of “rupture” in her recent article[vi] where there is a world before the rupture and a life after it. A world of continually streaming rhetoric of hyperbole, where “care” has become just another hackneyed phrase, the question remains that as this rupture perpetuates, who would have the means to survive it, to CARE and to be CARED for.

[i] PM CARES Fund- ‘Prime Minister’s Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations Fund’ PM CARES Fund was set up by the Government of India, for providing relief for emergency and distress situation on March 28th, 2020. Prime Minister’s National Relief Fund, set up in 1948, has similar objectives and is in function, in spite of which this new Fund has been set up, and has already attracted a large amount of donations from corporates, Ministries and Bollywood actors. Many of its provisions are ambiguous; regarding the amount of money collected, names of donors, the expenditure of the fund so far, or names of beneficiaries. The PM CARES Fund’s trust deed is not available for public scrutiny.

Priscilla Jebaraj, How different PM Cares Fund different from the PM’s National Relief Fund?, The Hindu, May 10, 2020.

Accessible link: https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-how-different-is-the-pm-cares-fund-from-the-pms-national-relief-fund/article31546287.ece

[ii] The film is created by Khwaab Tanha Collective. Accessible link for the film: https://www.instagram.com/p/B_pKsv6p5HL/. Look at https://www.instagram.com/oddbirdtheatre/ for more work made under this project.

[iii] Woh Todti Patthar (She Breaks Stones from the series, The World from my Balcony by Aastha Gandhi https://www.facebook.com/studio155artscollab/videos/979407682491448/

[iv] Accessible link: https://www.artsadmin.co.uk/events/4294

[v] Paru Episode 2 I CARE Accessible link: https://www.facebook.com/maya.k.rao/videos/10157311355647005.

For more of her work in response to migrant crisis, look at:

Watch That Train Watch That Girl. Accessible Link: https://www.facebook.com/maya.k.rao/videos/10157329533947005

[vi] Arundhati Roy, The Pandemic is a Portal, Financial Times, April 3, 2020. Accessible link: https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

From Spain – delayed reactions

Maria Delgado

On April 28th, I published a piece articulating the dismay that comments made on April 7th by José Manuel Rodríguez Uribes, Spain’s Minister of Culture and Sport, had generated amongst the sector whose interests and contribution to the economy he was supposed to champion. His comments that culture didn’t merit any special attention that this point (‘life first, then cinema’ he observed, (mis?)quoting Orson Welles), failed to acknowledge the role that digital entertainment, books, or streaming had played and were continuing to play during lockdown. Some governmental backtracking and embarrassment in the wave of a cultural backlash promised a reconsideration of the government’s position and May 5th saw a series of measures introduced to support the cultural sector as Spain emerges from a brutal lockdown and one of Europe’s highest death rates from Covid-19 – 25,857 at the time of writing (7 May 2020). Investment of €76.4m has come through Royal Decree, as legislation, and offers some concrete backing across a range of areas to, in the words of Uribes, ‘protect a key sector’.

So, what has Uribes delivered? Perhaps, most importantly, the possibility of accessing unemployment benefits for cultural workers for a period of up to 180 days – the sum is based on days of employment in the previous year. New financial incentives aim to assist with film shoots in Spain, there are expanded options for production subsidy, and streaming and TV screening are designated for the first time as constituting an ‘official’ premiere for film works, providing further flexibility to the cinema sector. €13m has also been earmarked to help cinemas to adapt to the new health and safety requirements in place as Spain emerges from lockdown.

Theatre and music are allocated approximately half of the allocated amount, with funds available for cancellations resulting from Covid-19 for contracts not greater than €50,000, targeted assistance for SMEs and incentives that recognise the need for support to bolster an infrastructure crippled by closed performance venues. The package introduced by Uribes also has a reduction in VAT on ebooks, and €4m assigned to assist independent bookshops. Incentives to assist with loans to the cultural sector and tax breaks to assist with investment in cinema, sponsorship and private donations to the arts also have a longer term aim to kickstart a sector that does not yet know when its theatres will open. Uribes’ comments that ‘we should not lose sight of the value, per se, of culture, which contributes to GDP but serves more as a pillar of the state as a right, as fundamental to the values and public ethics that we seek to preserve’ have gone some way to addressing the anger and dismay of the sector. Uribes’ initial hesitancy, however, to put any kind of package of support together may mean that he will struggle to win the trust of the cultural sector. Decisions have yet to be taken on festivals still scheduled to take place this summer, hampering planning from cultural organisations. Cultural leadership involves proactive forward-planning that acknowledges that this is a varied arts sector. Uribes’ package is just the beginning and how responsive and flexible he is able to be moving forward as a clearer picture of what the exit from lockdown will be for the performing arts may ultimately prove key in an effective, ethical and imaginative road to recovery.

https://thetheatretimes.com/culture-matters-lluis-pasqual-pedro-almodovar-and-spains-cultural-sector-respond-to-the-seeming-indifference-of-the-countrys-minister-of-culture/

Pandemics and Politics: Some Lessons from a Bengali Short Story

Mallarika Sinha Roy and Baidik Bhattacharya

Sharadindu Bandyopadhyay’s Bengali short story “shada prithibi” (1946) or “The White World” begins on an ominously theatrical note. The scene is set in London, and the protagonist is Sir John White, the preeminent scientist and philosopher of the day. On 6 August 1946, around 3 in the morning, Sir John suddenly finds the solution to the puzzling riddle that has occupied the most of his eighty-year long life. “Like the unbearable brightness of a thousand atomic bombs” a brilliant idea flashes in his head, and almost immediately he calls up a conservative British parliamentarian to tell him in a trembling voice that he has finally found the “salvation for the white races.” On 5 January 1947, an op-ed article in a “middle-rung Tory newspaper” elaborates on this plan and proposes a rather diabolical project. The author, using Malthusianism and social eugenics, argues that for the continued wellbeing of the white races it has become necessary to eliminate all the other races—“black, yellow, brown, mixed”—and to ensure the “survival of the fittest.”

The first incident takes place in the USA on 25 June 1948, when an unmanned aeroplane carrying a new prototype of atomic bomb accidentally crashes in the capital of Mexariz –. a state exclusively for the Black population – killing all inhabitants. This pattern repeats itself in South Africa, and then in South America. It is reported as the outbreak of an unknown virus that is asymptomatic but kills almost instantly. China, Burma, the Philippine islands, and countless other countries try to contain the spread of the pandemic through strict quarantine and restricted mass mobility. In India, the scene is no different. The first death occurs in Calcutta, on 7 June 1949. Within days, panic and the virus spread like wildfire, and the citizens of free (and in Bandyopadhyay’s imagination, undivided) India die like flies. By 6 August 1950, exactly after four years of Sir John’s inspired conception of the “salvation,” all the non-white races of the world are wiped out from the face of the earth because of this unknown pandemic.

Bandyopadhyay’s story compels us to rethink the fraught relationship between pandemics and politics. This is of course a long history as several studies have shown. In his lecture series Abnormal (1974-75), Michel Foucault shows how the management of plague pandemics in Europe between the Middle Ages and the nineteenth century produced some of the central templates of the modern state, especially the individualized subject and the elaborate mechanisms of surveillance. Closer home, David Arnold’s Colonizing the Body (1993) argues that the finer nuances of the colonial state in India between 1800 and 1914 were shaped by the state’s response to large-scale epidemics like smallpox, cholera, and plague, as also by the deployment of the idea of public medicine, distinct from traditional medical practices.

Our contemporary world, what historian Tim Mitchell calls “carbon democracy,” is reliant on the international mobility of cheap labour. The violence around the scramble for oil, as oil is the primary fuel for carting the labour from one location to another, is exactly proportional to the coverage of finance capital. In the current pandemic language of “lockdown” precisely this mobility comes to an absolute halt. As the juggernaut of market economy collides with the impenetrable fear-psychosis of pandemic, the world economy crumbles. Elimination of Human Rights for the economically vulnerable migrant population strengthens state power, but in absence of pharmaceutical measures and proper public health policies such enhancement in state power leaves the national population, the “self” of West, open to any “accidental” spread of the disease.

Bandyopadhay’s story, however, points toward another possibility. Instead of taking us through the emerging techniques of governance as we worry about the possible political life after Covid-19, it simply suggests pandemic as an end of politics. In Sir John’s Manichean scheme of things, the world is simply divided between two groups—the whites and the nonwhites—and it is the annihilation of the latter that facilitates the survival of the former. However, pandemics have their own ways of asserting lives and disturbing the neatness of a conservative fantasy. In the final section of the story, Sir John attends a large gathering in London and defends his diabolical project by arguing that mother nature is beyond human emotions like sympathy and kindness as she only favours the fittest. With great pleasure he informs the huge gathering that the plea for survival of the white races have been accepted at the court of mother nature. At this point Sir John suddenly stops and, like so many millions of non-white people before him, falls headlong on the dais and dies.

Locked down @ Home – vulnerabilities in private spaces

Urmimala Sarkar Munsi

Lockdown is becoming a habit for me and some others, a comfort zone rediscovered - so much so that I felt relief and satisfaction mixed with just a small amount of discomfort at the thought of the stay-at-home orders being extended for the second time in the “Red Zones” in India on 1st May, 2020. My home has become my haven, my performance space, my office for a part of the day – a safe space re-occupied. A particular line of thought has started troubling me from the days of beginning of this hyper-engagement with the idea of home. For many the home is a shared space – inhabited by members of all genders, of all age. What if that home is not a “safe space”?

Home, in the time of Covid-19, means enforced confinement. As the significant increase in numbers of domestic and child abuse cases reported across the world are getting compiled, it becomes evident that conflict / violence and overall increase in aggressiveness are again being justified as a fall-out of frustration (more in male members that females as usual). All such behavioural problems are being seen as a result of the family being still seen as the socialising tool that trains people to think in a way that justifies inequality and hierarchy.

The lockdown has become the justification for a huge rise in domestic violence against women and girls. The UN Women reports,

As more countries report infection and lockdown, more domestic violence helplines and shelters across the world are reporting rising calls for help….. Even before COVID-19 existed, domestic violence was already one of the greatest human rights violations. In the previous 12 months, 243 million women and girls (aged 15-49) across the world have been subjected to sexual or physical violence by an intimate partner… If not dealt with, this shadow pandemic will also add to the economic impact of COVID-19. (April,2020)

Radical Marxist Feminists have argued that women in the performative roles of “home-makers”, have absorbed the anger and frustration created by work and exploitation in the men, as patriarchy allowed the father a position at the top of the family hierarchy over wife/ partner and children. In the readings often are explanations of how this has led to an extraordinarily high number of cases of misuse of powers of physical and sexual abuse, usually kept hidden well under the carpet, by the victims themselves. Re-assigning the performance of age-old roles and hierarchies, as a default system of overall renewed 24 X 7 [enforced] coexistence for all, is what is bringing in once again the justification of misuse of power, misogyny, tolerance, and boundaries of rights – including the rights to sexual / oppressive / controlling behaviour and use of force.

To see the progress made in recent years through laws, social and economic freedom as well as developing consciousness of women’s and child rights come undone as the family face renewed “togetherness” that often becomes the utopic musings on family ties on social media posts nowadays, is therefore a sad reminder that patriarchy and misogyny are states of deep-rooted power politics, and control mechanism. As the lockdown orders extend, many women and children dread staying with the “man” in the family, as they face the terror of being locked down in the most unsafe space on earth for them – a space called “home”, without means of escape - isolated from the mechanisms of support that can help them.

References:

Kate Brady, “Coronavirus: Fears of domestic violence, child abuse rise | Coronavirus and Covid-19 - latest news about COVID-19 | DW | 19.03.2020”, Deutsche Welle News Service, https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-fears-of-domestic-violence-child-abuse-rise/a-52847759. Accessed 0n 1-5-2020.

Vandana Mohandas, Misogyny in the time of coronavirus lockdown: Can the sexist jokes stop now?” Thenewsminute, OPINION | SATURDAY, 28.03.2020, https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/misogyny-time-coronavirus-lockdown-can-sexist-jokes-stop-now-121316. Accessed on 01-05-2020.

Sue Scheff, “Teens, Cyberbullying, Sexual Harassment and Social Media: The New Normal?” HuffPost Life, 25.02.2016. Updated 24.02.2017, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/teens-sexual-harassment-a_b_9310060. Accessed on 01-05-2020

“Telangana childline has received many complaints of child sexual abuse and violence since lockdown”, The News Minute, 26.04.2020, https://in.news.yahoo.com/telangana-received-over-200-complaints-082800150.html. Accessed on 01-05-2020.

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka (Executive Director of UN Women), “Violence against women and girls: the shadow pandemic”, 06.04.2020, https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stories/2020/4/statement-ed-phumzile-violence-against-women-during-pandemic. Accessed 01-05-2020.

So What? The Necropolitics of Jair Bolsonaro

Ana Bernstein and Dora Silveira

With the highest transmission rate of Covid-19 in the world, Brazil is set to become the country with the second highest weekly death toll. Yet, despite a collapsing health care system, mass graves and morgues full to capacity, so far only one state governor has implemented lockdown measures; most have only recommended social distancing with less than half of the population reportedly staying at home. While the humanitarian crisis spirals out of control, President Jair Bolsonaro insists on denying the threat of the virus, pushing for the re-opening of the economy - even though it was never actually closed. Brazilian streets are rarely empty; and while liberal professionals get to work from home with little or no salary reductions, informal workers don’t have the luxury of sheltering in place. They are forced to choose between starving or contracting the virus. Street vendors are out selling masks and hand sanitizer. Buses and subways remain overcrowded. In March alone, more than 200 thousand Brazilians have signed up for a job in food delivery apps. These workers, who often need rented bikes to work, receive no hazard pay, no insurance, and no PPE.

The president, who says that "Brazil cannot stop” and "the economy comes first”, seems determined to make this pandemic as deadly as possible. In addition to multiple television appearances assuring the people that governors implemented social distancing measures to ruin his chances of re-election by hurting the economy, his most avid supporters have taken to daily protests, honking in front of hospitals while doctors and nurses work around the clock despite delayed salaries and the lack of PPE. Dressed in flags and dancing with makeshift coffins, enacting the famous meme of Ghanaian pallbearers, these fanatics call for the closing of the Supreme Court and the Congress, and the return of the military rule. The president joins these protests not only virtually, in live video transmissions, but also in person, attending various acts against democracy in which he mingled with the crowd without a mask, despite the fact that more than 24 members of his immediate entourage have tested positive for Covid-19.

While Bolsonaro presides over his death cult, millions of Brazilians line up for government assistance. The emergency aid is a measly 600 hundred reais stipend for 3 months. In order to receive it, people have been gathering in front of banks all around the country. The images are violent: crowds, standing for hours and often all night, huddle together waiting for assistance. Many of these are informal workers who made as much as three times the amount offered, and one third of them have not been able to get any assistance at all, lacking documents or other requirements. Millions live in crowded favelas without access to clean water and basic sanitation, and where large families share one-room dwellings.

When these people get sick, they will need the public health care system, which has had its budget severely slashed over the last years and been demonized by neoliberals, who have been trying to abolish it for decades. Unequipped to assist a country of continental dimensions, the public health care system is already in a state of collapse. Nothing like a contagious virus to bring in sharper relief what the left has been advocating all along: a system that takes care of everyone and not just the privileged few. Instead of sending help, the federal government has sent a questionnaire to each mayor, to determine how many bodies can be buried in each town. While other countries have injected massive public resources to shore up the economy and implemented policies to assist the population, the Minister of Economy, a hardcore defender of austerity, used the situation as an opportunity to further cripple worker's rights, allowing corporations to dismiss workers, reduce their hours and cut their wages.

Abandoned by the federal government, Brazilians are coming together to help one another. Numerous networks of solidarity have emerged to help those most in need, donating and distributing food, cleaning supplies, and PPE. Activists are proposing new legislation to protect essential workers, while university research centers and businesses repair and produce ventilators. In some favelas, gangs have imposed a curfew and are distributing supplies of hand sanitizer and masks. A fragmented and lethargic opposition is starting to come together. Every night, around 8PM, Brazilians all over the country go to their windows to bang pots protesting the government, demanding Bolsonaro's impeachment.

Amazingly, Bolsonaro still has the support of a significant segment of the population. As the death toll rises, his popularity is expected to drop. How many people will need to die before that happens? After all, this is the country where as many as 60,000 people are murdered every year. Given its history of hiding corpses - a common practice during dictatorship and still in use by the police and the state - Brazil is also, unsurprisingly, one of the countries that performs the least amount of tests: the independent estimates of cases and deaths are at least ten times higher than the official numbers. Arthur Chioro, the former Minister of Health during President Dilma Roussef’s administration, has warned that the death toll might reach one million. But the president has made it clear that he does not care. As Brazil reached 5,000 deaths (on April 28), he was asked by journalists about the increasing death toll. Bolsonaro replied, “So what? I’m sorry, but I can’t do anything.”