Nadine Holdsworth

Immigration and the Rise of the Far Right

1.1 Nadine’s Narrative Begins Here:

Born in 1969 and growing up in 1970s and 1980s Britain, racism was a daily battle. Two of my best friends during primary school were black – Sharon Watson and Vernica Bent - they constantly faced derogatory comments and abuse. The most trouble I ever got into at school came when I punched a boy for calling my friend a ‘smelly black bastard’. I still remember the fierce sense of injustice when I was hauled in front of the headmaster when it so clearly should have been my ‘victim’ made to apologize. So, as a young girl I was acutely aware of the tensions caused by race and immigration – I was aware of my friends’ distress, skin-heads who skulked around the school gates looking to recruit other white working-class youths to their National Front cause and my wider political consciousness can be traced back to the inner city ‘race’ riots that spread across Britain in the early 1980s.

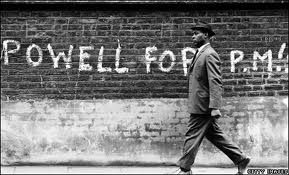

1.2 The racial discord circulating around Britain during this period had many contributory factors but the torch paper came with the Conservative politician Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ Speech that he delivered on 20thApril 1968 (the anniversary of Hitler’s birth).

Here is a the incendiary speech http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=23MEL7424aQ

The impact and legacy of this speech was recently reassessed during the 40thanniversary of its delivery. Here is a short extract from a BBC documentary http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HP7fETsKYkA

1.3 Enoch Powell picture gallery

|

|

|

1.4 Nadine Continues:

Enoch Powell was sacked from the shadow cabinet with his speech denounced by his fellow MPs, but his views received widespread popular support, for example thousands of workers staged strikes in protest at his sacking and marched to Downing Street to show their support for his views. Powell made his speech following the sudden influx of Kenyan Asians into Britain after they were driven out of Kenya by laws denying them employment. At the beginning of 1968, up to 1,000 Kenyan Asians, who held British passports as citizens of the Commonwealth, were arriving in Britain each month. Amid growing unrest, the government rushed through the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in March, which restricted the number of Kenyan Asians who could enter the country to those who had a relative who was already living in Britain.

In November 1968 a new Race Relations Act was introduced. This new act made it illegal to refuse housing, employment or public services to people because of their ethnic background. This followed up Britain’s first Race Relations Act in 1965, which resisted the ‘colour bar’ by making it illegal to discriminate against non-white people in public places such as pubs or cinemas. The 1968 Act also extended the powers of the Race Relations Board to deal with complaints of discrimination; and set up a new body, the Community Relations Commission, to promote ‘harmonious community relations’. Both Acts were replaced by a third Race Relations Act in 1976, which significantly strengthened the law by defining direct and indirect discrimination. 1976 also saw the foundation of the Commission for Racial Equality.

1.5 Despite this progressive legislation, the British National Front, a right-wing whites only political party that stood against immigration and supported policies of compulsory repatriation was gaining ground (the British National Party was formed as a splinter group from the NF in 1982). The Party grew during the 1970s, largely amongst white manual workers who resented immigrant competition in social housing and the labour market and amongst disillusioned far-right Conservatives who felt that their Party was not getting to grips with immigration. There was an upsurge in racist attacks, but this was countered by large-scale anti-racist demonstrations by the Anti-Nazi League - founded in 1977 to counter NF propaganda. In the cultural sphere there were also significant moves to recognise the increased complexity of British cultural identity e.g. Rock Against Racism formed in 1976.

1.6 David Edgar’s play Destiny (the Other Place, Stratford, 1976) tackles the history of British imperialism, colonial rule and contemporary politics that coalesce in this complex political moment when far-right political discourse fought to secure political legitimacy. Beginning in India in 1947 at the beginning of the end of the British Empire and ending with the rise of the Nation Forward Party (National Front) in the 1970s, in this play Edgar examines the multiple factors contributing to the rise of the far-right in Britain. This is a powerful, well-intentioned and important piece of Brechtian-style epic theatre that charts this period from the perspective of a white progressive left-wing liberal playwright. I have selected two extracts from this play:

Act One, Scene 4 – Act One, Scene Six, which charts the attraction of a politics of the far-right to the characters Rolfe and Turner who have both returned from serving in the British army in India to find a Britain they no longer recognize and the scene that depicts the initial impact of Powell’s speech for a pro-fascist group.

Act Two, Scene 6 – Act Two, Scene 8, shows the fight to secure political legitimacy for a far-right agenda and the way that the far-right manipulated the traditional political ground of the left and right to do so.

1.7 Tara Arts was formed in 1977 as a response to a racist attack in which a Sikh teenager was killed in Southall in London. Tara’s Artistic Director, Jatinder Verma, was motivated by the need to participate in a politicised response to the climate of racial unrest the prevailed – part of a need to command a public presence and to find a ‘public voice as and for Asians’. Verma was born in Tanzania to Indian parents, lived in Kenya, East Africa until the age of 14 and then came to Britain in 1968 as part of the wave of immigration that Powell railed against in his speech. All of Verma’s work with Tara Arts can be framed in relation to the experience of migration (personal and collective). The experience of the migrant has developed the enduring themes of Tara’s work that influences both the subject matter and the performance aesthetic.

Here is a link to a short piece in which Verma discusses the formation of Tara Arts and the impact of the political climate charted above.

Verma has argued that Black artists have the option of assimilating and integrating into dominant white culture and representations of blackness or confronting this culture with evidence of other histories, voices, forms, modes of representation and bodies and this is the route that Tara Arts has taken. As the company progressed the importance of establishing a distinct performance aesthetic that embraced the cultural presence and ‘ sensibility of the other’ took hold. Verma has called this performance aesthetic ‘binglish’ – a term that captures the qualities of hybridity, fusion, ‘not quite English’ and otherness that pervades the work of Tara Arts.

1.8 To mark the 20thanniversary of Tara Arts, the company embarked on a large-scale trilogy Journey to the West (1998-2002), which charts the journey of the Indian diaspora first to Kenya to work as indentured labour to build the East African Railway and then from Kenya to Britain (which prompted Powell’s speech) and then the journey this initiated in British society. What is particularly interesting about this piece is that it was an oral history project based on interviews with three generations of British Asians – it was a chance for the migrant, subaltern Asian voice to talk back about their experience. This ‘material’ was then used as the basis of a fictional account in three shows Genesis, Exodus and Revelations that formed the trilogy.

The following items that include a number of images, an extract from the programme for Revelations and an article about the production will give you a good sense of how the production worked.

Journey to the West

|

|

The documents relating to Journey to the West form the central bead of this string as they form a core of materials that enable us to explore how the impact of migration and its political ramifications have had a direct impact on theatrical methodologies, subject matter and performance aesthetics in a way that has enriched an understanding of what British theatre is and the stories that are now part of its national narrative.