Viruses: what are they good for?

What’s the first word that comes into your mind when you think of the ‘virus’? For most people, it’s probably ‘infection’, ‘flu’, ‘dangerous’, ‘disease’. And that’s hardly surprising since every time we hear anything about viruses it’s usually about an outbreak of a disease – think back to Ebola, Zika, Influenza, etc. But, what if there’s more to viruses than we give them credit for, and while some are bad, some might, in fact, be rather good?

Perhaps the best-known use of viruses in the science and technology industries is that of gene therapy. Viruses infect host cells by introducing their genetic material, be it DNA or RNA, into the cell allowing their genetic material to be replicated by the cell. Gene therapy relies on this ability of viruses; scientists are able to remove all the disease-causing genes from viruses and replace them with genes they want to introduce to patients. There have been over two thousand clinical trials for viral gene therapy, and a number of treatments have been approved.

One of the treatments which has received approval from the European Marketing Authorisation (EMA) is that for Adenosine-deaminase deficiency (also known as ADA-SCID). ADA-SCID is a genetic disorder which causes immunodeficiency; patients with a defective gene for adenosine deaminase, an enzyme without which the immune system is severely lacking or compromised. By replacing viral genes with functioning genes encoding adenosine deaminase, viral gene therapy aids in reconstructing the immune system in ADA-SCID patients.

Viruses can also be utilised in the treatment of some cancers. Oncolytic viruses are viruses which can infect and destroy cancerous cells. Clinical trials have revealed that viruses can be delivered to patients with limited toxicity, yielding positive results, particularly when treatment is provided alongside chemotherapy.

In 2016, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) approved the use of talimogene laherparepvec (better known as T-VEC) as a treatment for cancer within the NHS – namely, melanoma. Scientists genetically modified the herpes simplex virus, the causative agent of cold sores, such that the virus targeted melanoma cells, replicated inside them and subsequently killed them by forcing them to burst. The drug is injected directly into melanoma lesions, though recent research from the University of Leeds showed that T-VEC continues to have its cancer cell-killing ability even when injected into the bloodstream. The study revealed that white blood cells are able to reactive the virus as it makes its way to the site of the tumour via the blood.

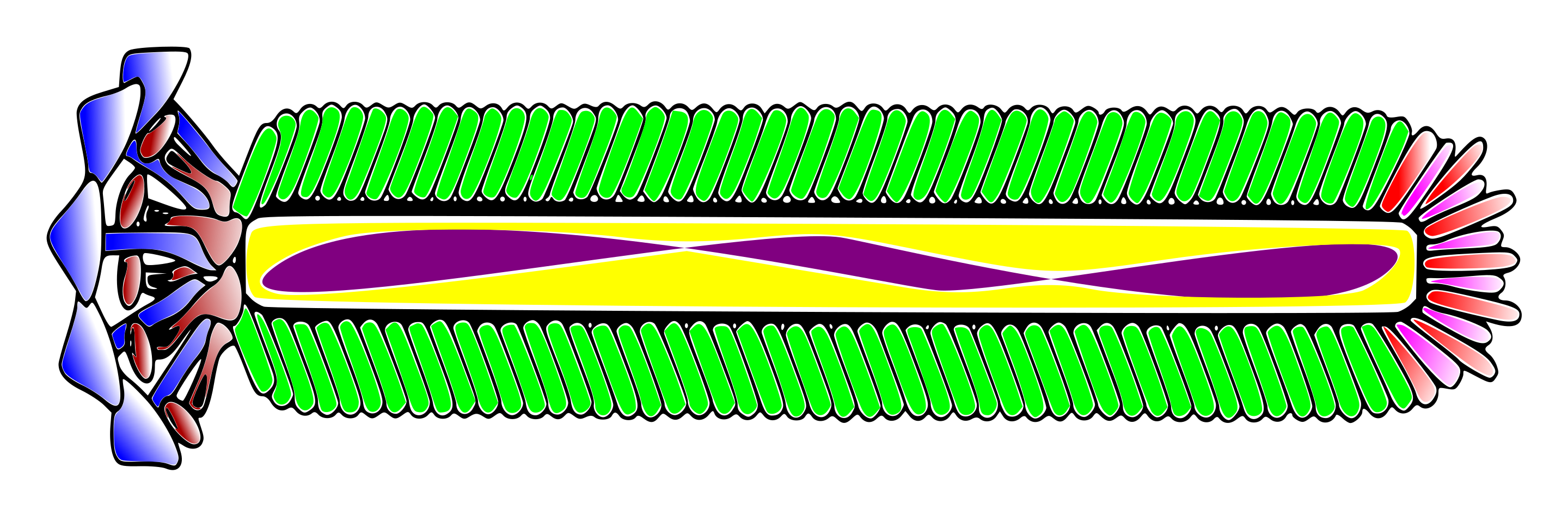

Aside from medicine, viruses are also being used in other fields, such as materials science. Viruses are being used as biological nanoparticle scaffolds for the growth of minerals, or as cages for the entrapment of substances from the environment. The bacteriophage M13 has been used in material science as a template to assemble nano-wires used in batteries. The M13 bacteriophage has also been used to harvest light; it was demonstrated that photochemical energy in the form of compounds called porphyrins spontaneously absorbed to the surface of the virus.

While there are many viruses which cause disease to humans, animals, and even bacteria, there are ways in which scientists to use and manipulate these viruses for the good of science. Be it in gene therapy, viral cancer therapy, or nanotechnology and material science, viruses do more than just harm.