Manage Perspective

Welcome to Perspective! Here you will find an exclusive edit of content produced by our exec and guest writers on topical matters that concern WWiE's aims & objectives. If you would like to contribute and are either a WWiE member or a professional working in the field of economics then please get in touch via email to discuss!

The Economic History of Race in the United States

Memorial to George Floyd in Minneapolis after he was killed by police officers. May he Rest in Power.

Motivated by the recent killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis which sparked protests worldwide and a wider discussion of racial oppression and police brutality, on Monday 22nd June, Professors Bishnupriya Gupta and James Fenske from the Warwick Economics department hosted a virtual event on the economic history of race in the United States. The speakers were Warren Whatley from the University of Michigan, Trevon Logan from Ohio State University, Jhacova Williams from Clemson University, and Bill Collins from Vanderbilt University.

A summary of the key takeaways from the talk and an overview of their research are as follows.

“The economic origins of African American family in the USA” – Warren Whatley

Warren Whatley set the historical backdrop for African American culture starting from the early 18th century. He shed light on the traumatic experience of Africans being forced into slavery in American Colonies and explained the term of double acculturation.

Double acculturation refers to the concept that enslaved peoples first had to culturally ‘become African’. They previously belonged to ethnically diverse native groups such as Igbo and Akan. However, they had to converge into an African commonality, even though this commonality for many was only skin deep. Once in America, circumstances required these individuals, who were treated as free labour, to form institutions amongst themselves as well as interacting with European-American power structures, thus their culture formed with influences from both Africa and America.

Whatley led up to the hypothesis that the driving force behind the creation and evolution of African American culture under slavery was the drive to reduce the probability of sale as a way to improve the quality of human life. For instance, African Americans’ strong sense of kinship during slavery stemmed from the fact that being a member of a family ensured stability because they were less likely to be traded. The use of African American here is in keeping with the specific historical terminology used by Whatley in his research.

Furthermore, such kinship relations created positive externalities for the community of enslaved peoples and these externalities were shared with their owners. Planters had reduced incentives to run away from their violent and exploitative working conditions and increased incentives to care. Most of the enslaved formed two-parent families when left in stable conditions i.e. no widespread selling. Additionally, there is evidence to suggest that traders did not trade husbands and wives and high birth rates increased the network value of mothers as caregivers.

The creation of the African American family under the duress of slavery is ultimately a great cultural achievement.

“The political economy of black reconstruction” – Trevon Logan

Trevon Logan’s research focused on the impact of black politicians on public finances and political violence against black people during the Reconstruction. The Reconstruction refers to the period leading up to and after the Reconstruction Act of 1867, which readmitted the southern states into the union after the civil war. This act required universal manhood suffrage, meaning that for the first time, African American men could vote and enter the political sphere.

The emancipation of slaves occurred with zero wealth redistribution. There was lots of arable land in the south that was not being put into production, so black politicians wanted to tax this land as a means of using tax policy to redistribute wealth to black communities where education and funding levels were much lower.

Logan found that places that had a lot of free black people, had a lot more black politicians during the Black Reconstruction. Free blacks refers to the legal status given to black people who were not enslaved or were born free. Additionally, he finds that the marginal effect of black politicians on local public finances, in the form of additional tax revenue per capita, is significant at $0.09. Therefore, due to black politicians setting higher taxes compared to areas that had no black politicians, black officeholders were related to both human capital gains and increased tax revenue. The political gains during the Reconstruction era were significant and an omitted factor in black economic history.

However, from 1870-1880, the relationship between higher tax revenues and black politicians became negative. Counties with more black politicians during the Reconstruction had slightly lower per capita taxes in 1880 due to these areas experiencing political violence with the intent to remove black politicians from office as a result of their tax policy. This prompted black politicians to bring their taxes back in line with areas with non-black officeholders. Black political success and the subsequent political violence that black politicians faced is an important, yet overlooked part of black economic history.

“Historical lynchings and the contemporary voting behaviour of black people” – Jhacova Williams

Jhacova Williams’ research focused on whether there is a link between racial animus and the contemporary voting behaviour of black people, using historical lynchings as an index for racial animus.

The aforementioned Reconstruction Act of 1867 changed the voting structure of the south by giving one million black people and 300,000 illiterate and poor whites the right to vote. Voter turnout ended up being 90%, which is unheard today. Black men voted for both black and white politicians. However, violence arose to suppress the black vote. The KKK killed more than 2,000 black people in Louisiana, two South Carolina legislators and the President of the Union League. The Union League was a network of quasi-secretive men’s clubs established during the civil war to promote loyalty to the Union of the United States. Consequently, black voter turnout was reduced by 20%.

Lynchings were related to voting. Notably, the reason for one of the most well-known lynchings, that of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in Mississippi, was explicitly related to voting. Although there is and was a common misconception that Till was murdered for whistling at a white woman, his killers who were found not guilty, admitted in an interview that “ I just decided it was time a few people got put on notice. As long as I live and can do anything about it…N*****s ain’t gonna vote where I live”.

Emmett Till

As a result, lynchings successfully changed behavioural patterns among black people and instigated apathy towards voting in black communities, presumably to avoid such violence happening to individuals and their children. Williams’ research found that in areas where there were historically higher rates of lynching, there are fewer registered black voters. This relationship was statistically significant for black citizens and insignificant for whites. She finds that this relationship is also unlikely to be driven by Republican party dominance, incarceration rates of black people, institutions that remained after slavery, geographic sorting, or contemporary barriers to voting.

One potential reason that Williams gave for this finding was that lynchings were essentially illegal killings that largely went unpunished and what that signified was officials cannot, or would not, protect black people. Therefore, a lack of trust in officials has persisted over time and will continue to persist, demonstrated by low levels of black voter turnout today. Although not explicitly mentioned by Williams, such a manifestation of distrust and fear could be a component of intergenerational trauma across black communities.

Williams also advocated for the need to expand voting methods to increase accessibility and for automatic registration to vote upon turning eighteen. The resistance to online voting, in particular, she considered to be another form of voter suppression.

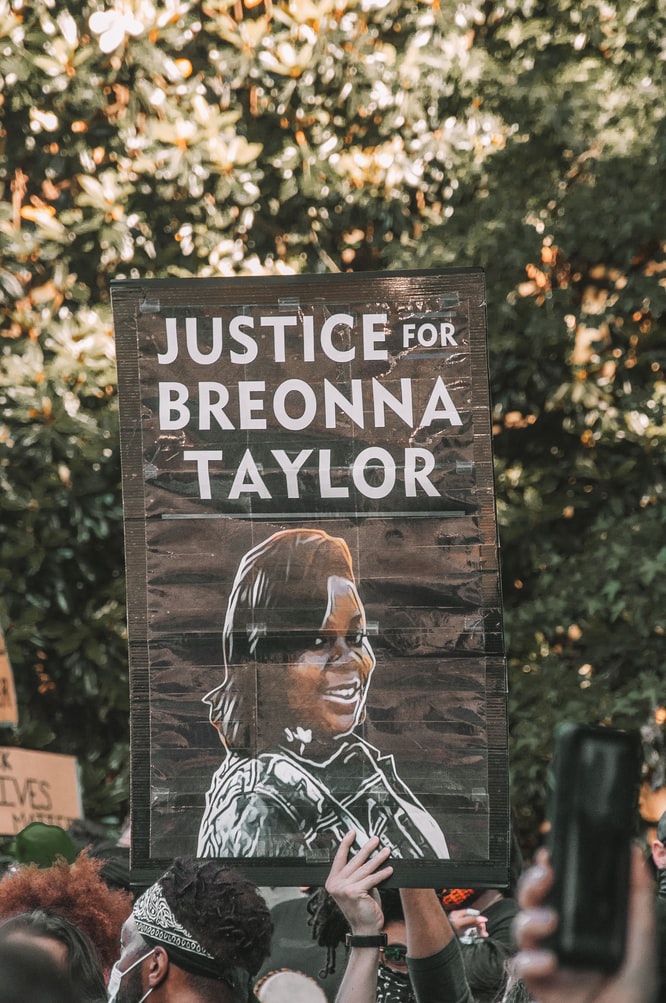

Breonna Taylor was killed by Police on 13th March 2020 while she slept in her bed. May she Rest in Power.

“Race, Unions and Wages: The US North and West circa 1950” – Bill Collins

Bill Collins’ research question was if northern black men had held union jobs at the same rate as similar white men, what would their wage distribution look like? The historical context to his research was the Great Migration, which refers to the large scale movement of blacks from the south to northern cities. For instance, in 1910, there was a heavy concentration of black people in the south and by 1970, the largest share had relocated to New York.

The Great Migration specifically happened in the 1940s and 1950s and the cities where people were migrating to, were also the cities that were becoming most unionised. There has been a long history of tension and violence between black workers and unions and gaining entry to union jobs was difficult for black people.

Collins’ results show that northern black men’s wages would have been between nine to ten per cent higher at the median if they had gained entry to union jobs at the same rate as white men with similar age, education and veteran status etc.

End remarks

At Warwick Women in Economics, we advocate not only for economic policy impact assessments on gender equality and highlight the unsuitability of many economic models to explain female agents’ behaviour, but also believe that an intersectional approach to economics must become the new norm, with racial inequalities a key indicator in these considerations.

Upon conclusion of the webinar, the topical question was posed; is it possible for the current neoclassical economic paradigm not to be racist if many of the foundations are so rooted in racism? It’s a complex question, one that this article does not feel it can do it justice, highlighting the necessity of a decolonised curriculum in schools and universities if we are to learn from mistakes and promote a progressive future. All in all, it is clear we cannot truly dismantle systemic racism until we address the racism within the economic system and the syllabus.