Refugees are not just another group of immigrants, column by Sascha Becker

Refugees are not just another group of immigrants, column by Sascha Becker

Tuesday 16 Jan 2024Original article written by Sascha Becker for the Luxembourg Institute of Socio-economic Research (LISER).

Sascha O. Becker, Monash University, Australia on “Understanding and responding to the new aspirations of refugees: going digital!”

Although the humanitarian justification for assisting refugees is obvious, it is crucial to recognize that the needs of refugees extend beyond basic necessities such as shelter, food, and survival. It is important to acknowledge that refugees differ from other immigrant groups in many ways, as they did not have the luxury of time to plan their moves across international borders, unlike economic migrants who might have had months or even years to do so. Forced migration is very different from voluntary migration. The experience of forced displacement results in a range of supplementary experiences and requirements due to the trauma involved (Becker and Ferrara, 2019):

- First, refugees have undergone (and continue to endure) physical and psychological suffering to an extent that is not comparable to voluntary migrants.

- Second, refugees have been stripped of their assets either through destruction or due to being forced to leave their homes in haste, with little hope of returning.

- Third, refugees frequently find themselves in sub-optimal locations, as their priority is to escape, and their options for choosing a destination are often limited.

- Fourth, refugees often have no say in whether their new location is temporary or permanent, which complicates planning for their future.

In such situations, education becomes a crucial aspect, especially for refugees who have lost their possessions and been forced to leave their homeland. This holds true for both adults and children. Refugee parents may have high aspirations for the education of their children, because education is a portable asset that can never be taken away (Becker et al., 2020). Similarly, adult refugees may aim to learn the language of their new host country and develop vocational skills to help them adapt to their new environment.

Uprootedness may lead to a desire to invest in education

History can teach us valuable lessons because we can study not only the short-term challenges of refugees, but also the long-term effects over multiple generations. For some time, academics have considered the notion that being displaced by force and losing possessions enhances the preference to invest in portable assets, particularly in education (e.g., Brenner and Kiefer, 1981). This so-called “uprootedness hypothesis” can also be found outside academic spheres. In his bestselling autobiographical novel “A Tale of Love and Darkness”, Amos Oz gives a testimony of his Aunt Sonia:

“Why is she a roadsweeper? So as to keep two talented daughters at university… Food – they save on. Clothes – they save on those too. Accommodation – they all share a single room. All so that the studies and textbooks they won’t be short. It was always like that with Jewish families: they believed that education was an investment for the future, the only thing that no one can ever take away from your children, even if, Heaven forbid, there’s another war, another revolution, more discriminatory laws—your diploma you can always fold up quickly, hide it in the seams of your clothes, and run away to wherever Jews are allowed to live.” (Oz, 2005: 172)

Forced migration and preferences for education: the case of Polish migrants after WWII

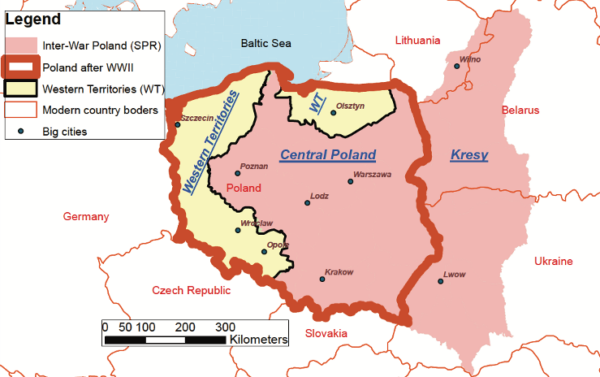

Following the end of WWII, the Polish borders underwent a significant redrawing, leading to a widespread forced migration. In Becker et al. (2020), our focus is on the plight of more than two million Polish migrants who were compelled to leave Kresy, an eastern borderland region of Poland that was annexed by the USSR after the war. These Polish expellees were predominantly relocated to the newly acquired “Western Territories”, which were taken from Germany (and whose German occupants were forcibly expelled). Some former inhabitants of Kresy were also transferred to the Central Poland territories, which were Polish during the inter-war period and remained under Polish control post-WWII.

Our research delves into the lasting consequences of forced migration in the aftermath of WWII, examining multiple generations of descendants of the original expellees, including children, grandchildren, and greatgrandchildren. Through the integration of historical census information and newly gathered survey data, we put forth our hypotheses and test them rigorously. Our findings reveal that individuals of Polish descent with a family history of forced migration exhibit significantly higher levels of education today than any other comparative group. The progeny of Kresy migrants, for instance, demonstrate an 11.2 percentage point increase in the likelihood of completing secondary education and an 8.8 percentage point surge in university graduation rates compared to other Polish subgroups. These disparities translate to an additional year of education for descendants of Kresy migrants, which in turn leads to improved labor market outcomes and substantially augmented incomes.

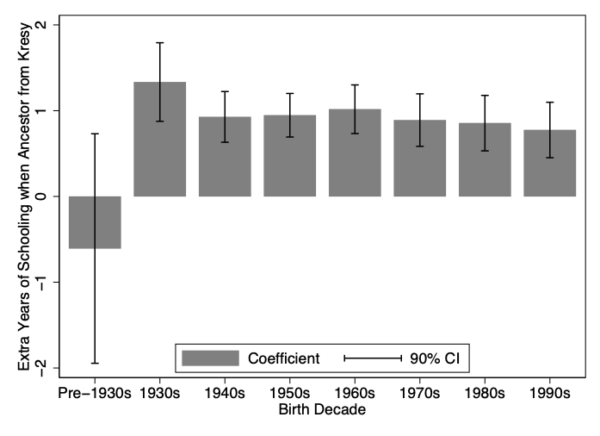

It is noteworthy that, prior to WWII, the Polish inhabitants of Kresy were, if anything, less educated than their compatriots in other regions. We demonstrate this pattern utilizing both survey data and historical census data. The historical trend reversal is noticeable in the first generation of children to receive an education following the war and persists over several generations, as shown in Figure 2.

Notes: The figure represents the estimated difference in years of education between descendants of Kresy migrants and other Poles by birth cohort. The brackets represent 90% confidence intervals around the point estimates.

The evidence we present strongly supports the “uprootedness” hypothesis: forced migration caused a shift in preferences toward investment in human capital as opposed to physical capital. In fact, our research shows not only more investment in education among refugees and their descendants than among non-refugees, but also a lower esteem for material goods. The latter is based on survey evidence that also shows a higher importance attributed to “freedom” among forced migrants. Together, this documents a shift in aspirations and a re-balancing of what they consider to be the most important in life.

Policy implications

In light of the lessons that can be gleaned from the history of mass displacement in Europe (Becker, 2022), it stands to reason that refugees and their offspring are likely to seek to make the most of their harrowing experiences. The experience of forced migration may generate new aspirations, after going through so much. As demonstrated in our research (Becker et al., 2020), access to education can serve as a beacon of hope in the wake of forced migration, empowering refugees to invest in a more promising future for themselves and their children. But there is a broader point. The success of the Polish case after World War II was also a result of integration starting from day 1. Any aspiration to get educated will be doomed if the access to schooling is delayed, not affordable, or outright impossible. Two policy recommendations emerge from our research.

The integration of refugees should be a day-1 priority

First of all, delays and bans to access education and training programs should not exceed an incompressible minimum. There are often bureaucratic bottlenecks. Refugees are given shelter and safety, but their integration often starts with significant delays. The UNHCR (2023) estimates that among the 20.7 million refugees under their immediate care there are 7.9 million refugee children of school age. Most of them are in less developed areas of the world where access to education is limited, implying that almost half of the refugee children are unable to attend school at all. Even in European countries, there are often extensive waiting periods before refugee children are assigned a place in school. Rod (2019) documented the case of a Syrian refugee girl in Germany who still had not attended school one year after arriving in Germany. Similarly, there is often delays to get work permits for parents, or access to language or occupational training. This is counterproductive for integration and damages not only refugees’ integration but also the host country.

Digital tools can be used to ease refugees’ integration

Second, it is crucial to have a good understanding of what the refugees themselves want, what are their difficulties, and what are their new aspirations. A bad comprehension of refugees’ incentives and constraints is harmful to the integration process and can lead to inefficient policies. What could we do? The more systematic use of digital tools can boost integration and kill several birds with one stone by: (1) better understanding refugees’ skills, their intentions, their difficulties and aspirations upon arrival as well as (2) providing information and online training programs to speed up integration.

Concretely, refugees could be asked on the day of registration to fill in an electronic questionnaire, to better understand their needs, their skill sets, their immediate plans, their medium- to long-term plans, to the extent the refugees themselves already know. Regular follow-up surveys (e.g., monthly or quarterly) that can be filled in from a mobile phone could help trace the integration efforts of asylum seekers (during the waiting period) and of refugees after their visa has been granted.

Furthermore, some training programs could be moved online or extended with digital tools. Assume a refugee declares in the online survey that they do not understand the local language at all. That could trigger a follow-up message (SMS or email) with a link to a language course with some basic expressions in the local language. Many more services could also be provided online. The use of digital tools would help to speed up integration and could complement face-to-face sessions that are important to network with other refugees and local administrators. The earlier we can meet refugees’ aspirations for a life in safety, the better it is for them, and for us.

References

Becker, S. O. and A. Ferrara (2019). Consequences of forced migration: A survey of recent findings. Labour Economics 59: 1-16.

Becker, S. O., I. Grosfeld, P. Grosjean, N. Voigtländer, and E. Zhuravskaya (2020). Forced migration and human capital: Evidence from post-WWII population transfers. American Economic Review 110(5): 1430-1463.

Becker, S. O. (2022). Forced displacement in history: Some recent research. Australian Economic History Review 62(1): 2-25.

Brenner, R. and N. M. Kiefer (1981). The economics of the diaspora: Discrimination and occupational structure. Economic Development and Cultural Change 29(3): 517-534.

Oz, A. (2005). A Tale of Love and Darkness. Vintage Books, NY City, USA.

Rod, J. (2019). Education for refugee children. Deutschlandfunk, 29 April. UNHCR (2023). https://www.unhcr.org/uk/education.html (accessed 17 April 2023)