Pandemics and women’s labour market participation in India: A long view

Pandemics and women’s labour market participation in India: A long view

Friday 20 Nov 2020The 1918 influenza pandemic had a positive effect on women’s labour force participation in India, but this effect was short-lived. Ashwini Deshpande and Bishnupriya Gupta consider the labour market effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and ask whether this time women’s labour force participation might change for the long term.

The 1918 influenza pandemic

The 1918 influenza pandemic ravaged through India, killing 5% of the population. Its impact was greatest on the working age population and varied across regions depending on weather conditions. The mortality rate varied across districts, but was similar for men and women.

The impact of the pandemic on women’s labour force participation was striking. In 1911, most women (73%) worked in agriculture and related activities – constituting one third of the workforce; 11% of women worked in industry, mining and construction, and the rest in service sector occupations. After 1918, women’s labour force participation rose in districts with high mortality, but this increase was not uniform across sectors: it increased only in the service sector. The mortality shock experienced by a typical district increased women’s labour force participation by 2.3 percentage points. Poverty drove many women to enter the labour market in this period. The number of widows rose in districts with high mortality, and widowhood was a possible reason why women entered the labour market.[i]

Demographic shocks, such as the World Wars, have resulted in enduring increases in women’s labour market participation in other countries. The change to female labour market participation after the 1918 influenza pandemic in India was, however, short-lived. By 1931 the effect had disappeared completely. This may have been due to strong social norms against women working.

But what has been the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labour market prospects for women in India? And are these effects likely to abide for the long term?

COVID-19

One major difference between the 1918 influenza pandemic and COVID-19 is the way the pandemics have impacted on the labour market. In 1918, there was a supply shock due to high mortality in the working age population. This can be seen in the increase in wages in some sectors. In 2020, the main labour market shock has been the lockdown due to which large numbers of workers lost jobs as factories and construction work shut down, and informal workers – especially urban service providers – were unable to work due to the compulsions of social distancing.

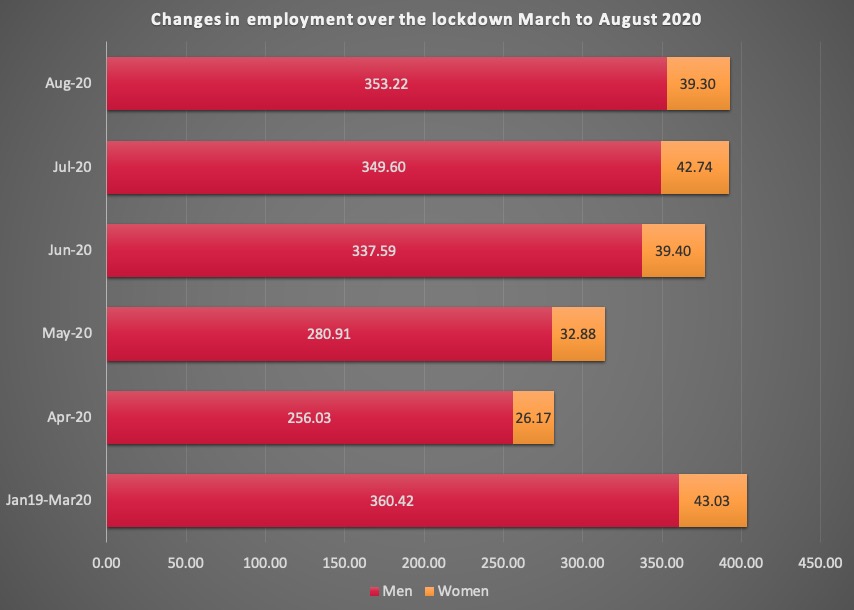

How did this effect women’s labour market prospects in India? Today, women’s labour force participation stands at less than a quarter of the working age population. Around 70% of women in rural India work in agriculture and 60% of urban women work in services and 30% in industry (Sundari 2020). In April 2020, the economic shutdown led to the biggest contraction in employment in the post-COVID period. According to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the average employment for January 2019 to March 2020 was 403 million. This declined to 282 million in April 2020 and recovered steadily thereafter to reach 393 million by August 2020. The corresponding figures for men are 360, 256 and 353 million, and for women, they are 43, 26 and 39 million, respectively. Thus, male employment in August 2020 is 98%, and female employment is 91%, of the respective pre-pandemic average.

Deshpande (2020) shows that when the lockdown was lifted, more men went back to work than women. Accounting for previous employment, women were 9.5 percentage points less likely than men to be employed in August 2020 compared to August 2019.

Effects of the pandemic on the labour force

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in more job losses for women than men.[ii] In contrast to the experience of previous recessions, women are more likely to bear the brunt this time because of the sectors hit by the shutdown, e.g. hospitality, retail, domestic and childcare services. The US labour bureau data for September shows that large numbers of American women are dropping out of the workforce altogether.

The impact of the pandemic on employment has been different in India. First, after the big contraction in employment in April, employment for both men and women has recovered steadily, but at a lower rate for women. Second, India has had a persistently large gender gap in labour force participation, going back several decades. The pandemic has increased this gap, but whether women are dropping out of the labour force in unusually large numbers due to the pandemic, as seen in the US and some other parts of the world, over and above the already low levels of participation in paid work needs more evidence.

Men are participating marginally more in domestic work

Indian women’s participation in paid work is already constrained by their responsibilities for domestic chores and care work. South Asia has one of the most unequal divisions of domestic work in the world. However, in the first month of the strict lockdown in India, during which domestic helpers and service providers were absent from work, men stepped in to help. Data reveal increased hours spent on domestic work by men and a consequent reduction in gender gap in domestic work. By August 2020, as domestic helpers returned to work, and men returned to their jobs, men’s hours spent on domestic chores declined, but did not fully go back to pre-pandemic levels.[iii]

Positive change for the future?

Despite the presence of two strong preconditions for women’s participation in paid work – falling fertility and rapidly rising female education levels – Indian female labour force participation has not only been persistently low but has registered a decline over the last 15 years. The experience of the pandemic teaches us that a normalisation of ‘working from home’ supposedly allows women to participate in paid work and simultaneously take care of domestic responsibilities. However, without changes that ensure more equality in domestic work as well as in paid work opportunities and more importantly changes in social norms about women’s work, we are unlikely to see a significant change in women’s participation in the labour force.

Ashwini Deshpande (Ashoka University)

Bishnupriya Gupta (University of Warwick and CAGE)

Further reading

Fenske, J., Gupta, B., and Yuan, S. (2020), Demographic shocks and women’s labor market participation: evidence from the 1918 influenza pandemic in India, CAGE working paper, 494

Deshpande, A. (2020), The COVID-19 Pandemic and Gendered Division of Paid and Unpaid Work: Evidence from India, IZA Discussion paper, No. 13815

[i] Taken from Fenske, Gupta and Yuan (2020), who study the effect of this demographic shock on women’s labour market participation using the differential mortality across districts in 1918 and the population censuses of 1901-1931.

[ii] See for example: https://www.bloombergquint.com/global-economics/women-s-job-losses-could-shave-1-trillion-off-global-gdp

[iii] Deshpande shows (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/100992/) shows that being primarily responsible for domestic chores is a constraint on women’s ability to participate in paid work. If this constraint eases, in future, we could expect women to increase their participation in paid work, if there is sufficient demand for their labour. For now, the increase in male hours is too small and too short-term to say whether it will definitely free up women for more paid work.