Economics and the study of race

Economics and the study of race

Monday 24 May 2021In 2020, the Econometric Society World Congress convened a panel event to ask ‘What can economics do for racial justice?’ A clear answer was that, alongside the tentative advances in teaching and the pressure to improve representation, economists need to study the causes and consequences of racial inequality. Arun Advani, Elliott Ash, David Cai and Imran Rasul examine how much economists have actually been doing this.

The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 sparked outrage across the world. The #BlackLivesMatter protests that followed brought the issues facing ethnic minority individuals to the top of the global news agenda and led many organisations to ask themselves what they are doing to tackle racial injustice. Academic economics has had its own reckoning, with discussions about what we teach (Alves and Kvangraven, 2021; Charles, 2021), how we teach (Bayer et al., 2020a), and who is represented (Advani et al., 2019, 2020; Bayer et al. 2020b; Koffi and Wantchekon, 2021). But alongside this, we also need to understand how much economists are seeking to address race-related issues in their research. We find not only that the causes and consequences of racial inequality are significantly under-researched in economics, but that economists over-estimate how much race-related research takes place within the discipline.

Race-related research is under-represented in economics

Using data from over 225,000 academic publications by economists over a sixty-year period (1960–2020), we determine what share of research can be classified as ‘race-related’. We develop an algorithm to automatically classify a publication as ‘race-related’ if it contains a group keyword such as ‘African-American’ (full list available here) and a topic keyword such as ‘discrimination’ (full list available here) in the title or abstract.

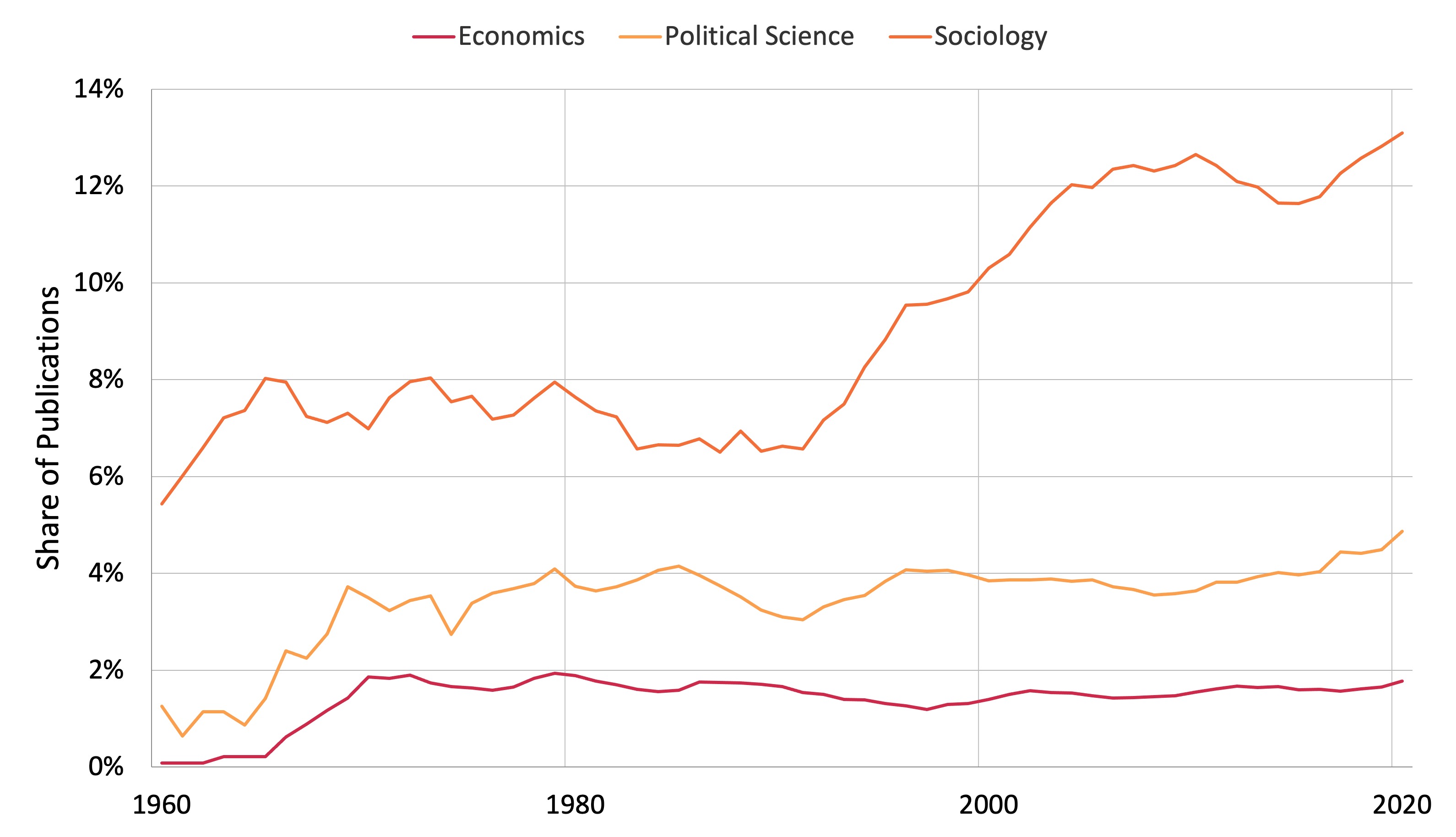

Figure 1 shows the share of publications in economics that we classify as race-related, over the past 60 years. Since around 1970, this has remained steady at a little below 2% of all publications in economics. Of the near quarter of a million publications in economics since 1960, only 3000 are race related.

We compare this data to two other social science disciplines: sociology and political science. Both disciplines are similar to economics, in that they cover a relatively broad range of social science issues, but with different methodological approaches. Economics produces far less race-related research, in terms of both the absolute number of publications and the share of publications that are race-related. In political science the share of race-related publications is more than twice that of economics, and in sociology it is around six times as high.

Figure 1: Share of publications that are race-related, by year and discipline

Notes: We use data from JSTOR, Scopus, and the Web of Science to construct the number and shares of race related publications in economics, political science, and sociology. All series presented are five-year moving averages.

Economists over-estimate the amount of race-related research within their discipline

To understand whether economists are actually aware of how little race-related work they do, we conducted a survey of economists using the Social Science Prediction Platform. We surveyed a mix of academics, recruited via direct emails and Twitter advertising, and public sector economists, recruited via the UK Government Economics Service and the Bank of England internal mailing lists. We gathered a sample of 240 responses from academic and public sector economists. Participants were asked to state their beliefs about:

- The share of race-related research in economics in relation to other disciplines

- How the share of race-related research in economics has changed over time

- How race-related research in economics is divided between the ‘Top Five’ and other academic journals.

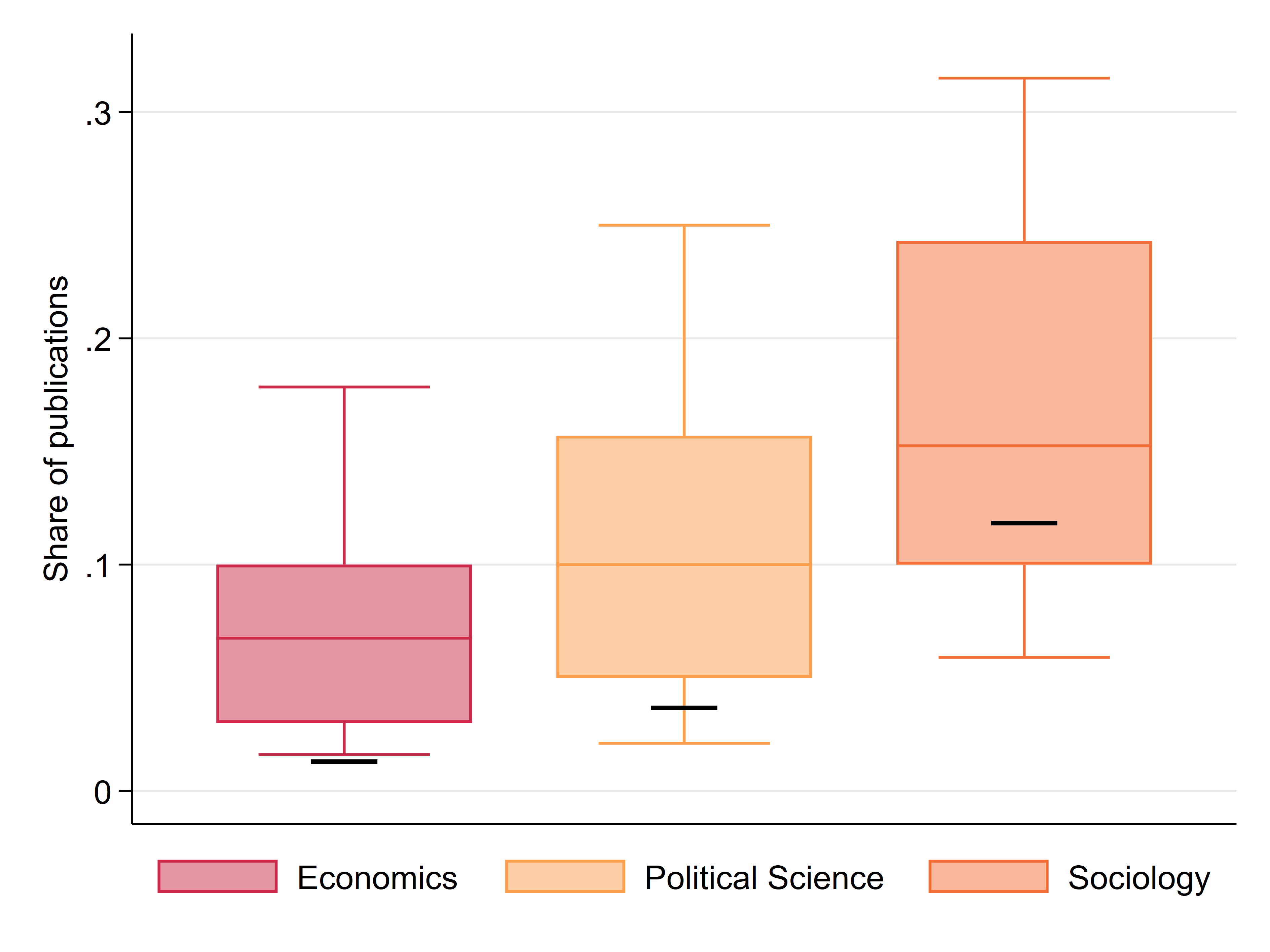

Economists correctly predict that political scientists and sociologists produce more race-related research than economists (Figure 2a). However, more than 90% of economists over-estimate the share of race-related research in their own discipline, with the median estimate four times the true value.

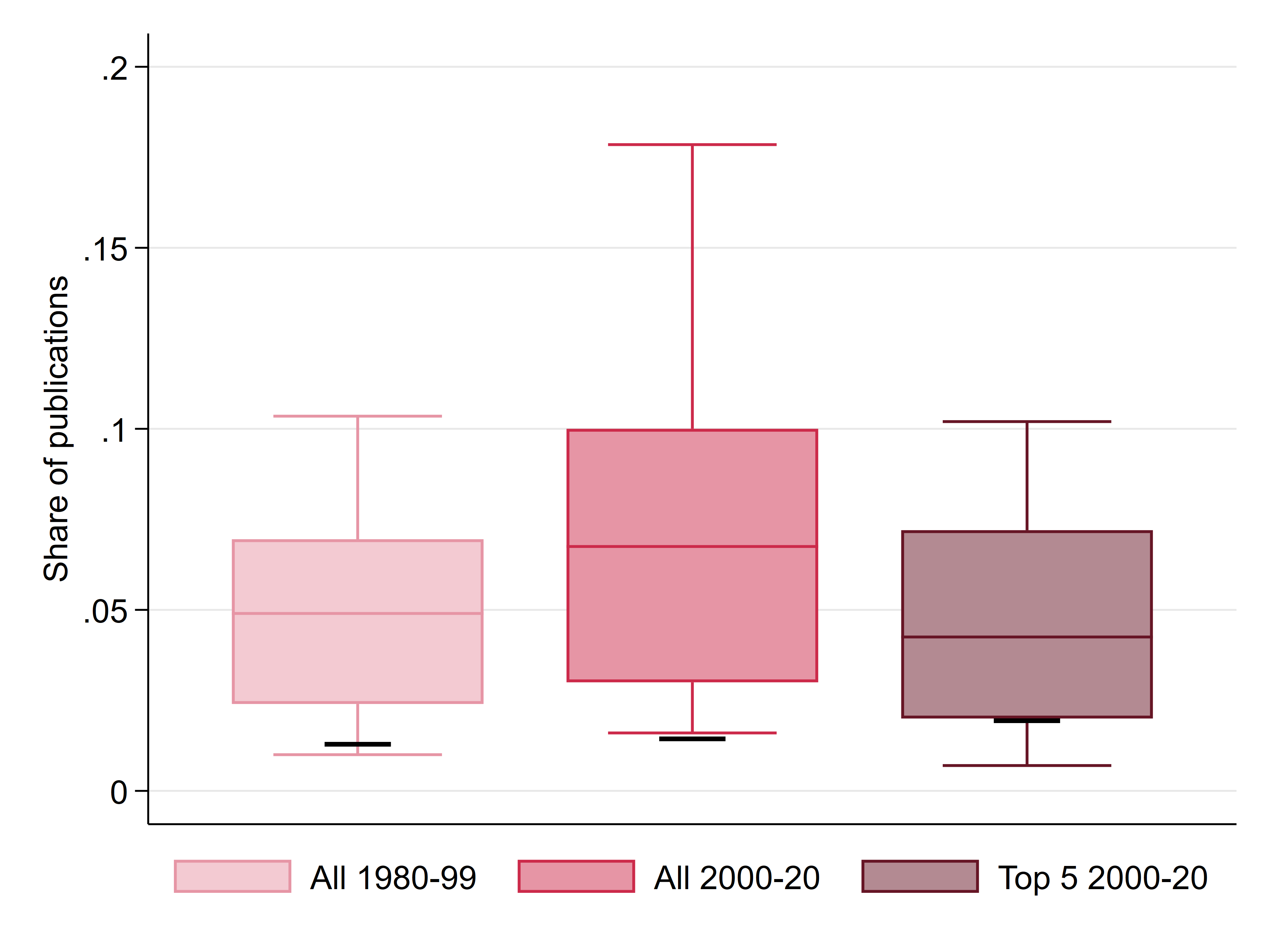

Looking at race-related research over time (Figure 2b), economists believe that the amount of race-related research has been rising substantially: the median estimate is that race-related research has risen by 40% for 2000–2020 compared with 1980–2000. In fact, it has risen by only 10%.

Almost 80% of economists think that the ‘Top Five’ journals are less likely to publish race-related research. Although this was true before 2000, the share of race-related papers in the Top Five has risen by almost 25% since 2000. Together these results show that economists are not well informed about the production of race-related research within their own discipline.

Figure 2: Social Science Prediction Platform results (N=240)

A. Predicted share of race-related research 2000–20, by discipline

B. Predicted share of race-related research in Top Five economics journals

Notes: We summarise results from a survey we ran on the Social Science Prediction Platform. Questions were of the form "What share of articles published in [discipline/journal type] between [dates] do you think were race-related?", and were asked after an explanation of our definition of a race-related publication. Panel A compares responses across disciplines, covering all publications 2000–20 in those disciplines. Panel B looks within economics to compare over time and between all journals and Top Five journals. The box-whisker plots show the 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles of responses. The black horizontal lines indicate true values as measured by our algorithm.

Where do we go from here?

The first step in encouraging race-related research is to correct misperceptions and ensure that economists recognise the current state of research in the profession. We hope that our findings will go some way to achieving this goal. But, if the situation is to change, it is important to understand why economists produce so little race-related research.

Is it that economics covers a broad range of topics, some of which are more amenable to incorporating a study of race than others? Perhaps – despite notable exceptions (Cook, 2014; Hsieh et al., 2019) – macroeconomists have little to say on this topic? Or is race-related research harder to publish – or publish in the most prestigious journals – creating a disincentive to do race-related work? Or, finally, does a lack of diversity within the profession mean that people who are intrinsically motivated to study such questions are unlikely to progress within economics?

Answering these questions is essential if the discipline is going to be able to reform and take seriously the need to produce more race-related research. Economics has the potential to do a great deal for racial justice. The challenge is to understand the barriers holding it back.

Arun Advani, University of Warwick

Elliott Ash, ETH Zurich

David Cai, ETH Zurich

Imran Rasul, University College London

Further reading

Advani, Arun, Rachel Griffith and Sarah Smith (2019). Economics in the UK has a diversity problem that starts in schools and colleges. VoxEU.org, 15 October

Advani, Arun, Sonkurt Sen and Ross Warwick (2020). Ethnic diversity in UK economics. IFS Briefing Note 307

Advani, Arun, Elliott Ash, David Cai and Imran Rasul (2020). Race Related Research in Economics and other Social Sciences. CAGE working paper (no.565) [forthcoming in Econometric Society World Congress monograph]

Alves, Carolina and Ingrid H. Kvangraven (2021). Does economics need to be ‘decolonised’? Economics Observatory, 20 January

Bayer, Amanda, Gregory Bruich, Raj Chetty and Andrew Housiaux (2020a). Expanding and Diversifying the Pool of Undergraduates who Study Economics: Insights from a New Introductory Course at Harvard. NBER Working Paper 26961

Bayer, Amanda, Gary A. Hoover and Ebonya Washington (2020b). How You Can Work to Increase the Presence and Improve the Experience of Black, Latinx, and Native American People in the Economics Profession. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(3) p.193–219

Cook, Lisa (2014). Violence and Economic Growth: Evidence from African American Patents, 1870- 1940. Journal of Economic Growth, 19(2) p.221–257

Cook, Lisa (2021) Transcript of Remarks from ‘What Can Economics do for Racial Justice?’ panel, Econometric Society World Congress Monograph.

Charles, Kerwin (2021) Transcript of Remarks from ‘What Can Economics do for Racial Justice?’ panel, Econometric Society World Congress Monograph.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai, Erik Hurst, Charles I. Jones and Peter J. Klenow (2019). The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth. Econometrica, 87(5) p.1439–1474

Koffi, Marlène and Leonard Wantchekon (2021). Racial Justice from Within? Diversity and Inclusion in Economics. Econometric Society World Congress Monograph.