The rise of the Chinese Communist Party

The rise of the Chinese Communist Party

Tuesday 27 Jun 2023In the 1930s and 40s the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) clawed its way back from near obliteration to become the dominant party in China. It is now the second largest political party in the world. But how did it do it?

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP), second in size only to the Indian People’s Party, has shaped modern politics. Whether seen as a challenge to Western democracy or as a mechanism to rejuvenate the world order, there is no denying it has established itself as a dominant global power.

But it wasn’t always this way.

In the mid-1930s, the CCP was fighting for survival as the smaller of two political parties in China. What happened to turn the fate of the party around?

At the Crafts Lecture 2023, James Kai-Sing Kung (University of Hong Kong) shared his findings on the dramatic fall and rise of the party in the 1930s and 40s. His data, collected with co-author Ting Chen, tells a story of violent circumstance and the rise of nationalism.

The tussle for power in 1930s China

The CCP started out as an urban movement. Strongly influenced by the Communism of the Soviets, its leaders sought to attract membership from labour unions and industrial workers.

But competition for the hearts and minds of these groups was fierce. While the CCP managed to gain some new members, especially from student audiences, it couldn’t match the strength of the dominant political party of the era, the Kuomintang, or KMT.

The KMT was, however, unsettled enough by the rising membership of the CCP to seek to silence it. From 1927 an intermittent civil war between the KMT-led government and the CCP broke out, driving the CCP first out of urban areas into rural towns and villages, then much further across the country.

The CCP’s retreat to rural areas forced it to re-evaluate its approach. In terms of numbers, the opportunity for expansion was good. While there were 2 million workers in urban areas, there were around 200 million peasants in the countryside. And as the CCP worked to establish itself in rural areas – ‘encircling the city with the countryside’ – it came to realise their importance for the cause.

It was after connecting with rural civilians that Mao Zedong, who had started to rise to prominence in the CCP, began to understand the complex ‘agrarian problem’: Most rural peasants were poor, but their landlords were not wealthy, so redistribution (to meet the ideals of communism) would not be simple. Mao also realised that hurting rich peasants could easily backfire, and that poor peasants would not invest in land they did not own.

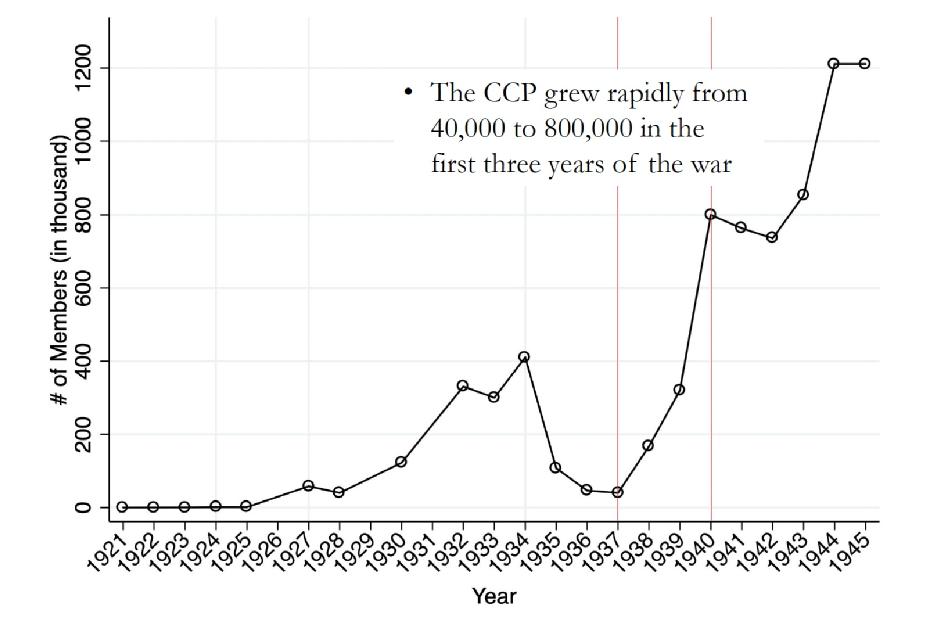

The effort to understand the plight of rural peasants had some success. Between 1927 and 1934 CCP membership grew from around 40,000 to 400,000 members.

But success was short lived. In 1934, the KMT pushed the CCP back further still, forcing the famous Long March – a retreat of over 9000km across China.

CCP membership plummeted by 90%. The future of the party looked bleak.

Yet, in 1937, another bloody change of circumstance unexpectedly altered the fate of the CCP. Japan’s invasion of China (triggering the Second Sino-Japanese War) changed the balance of power between the KMT and the CCP, and set up the context for a meteoric rise in CCP membership.

Figure 1: Membership of the CCP grew rapidly at the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War

Japanese invasion, 1938

The invasion of Japan was fierce and bloody. Around 7.5 million civilians were killed (1.4% of the total population in 1934) and 2.2 million women were raped by Japanese forces.

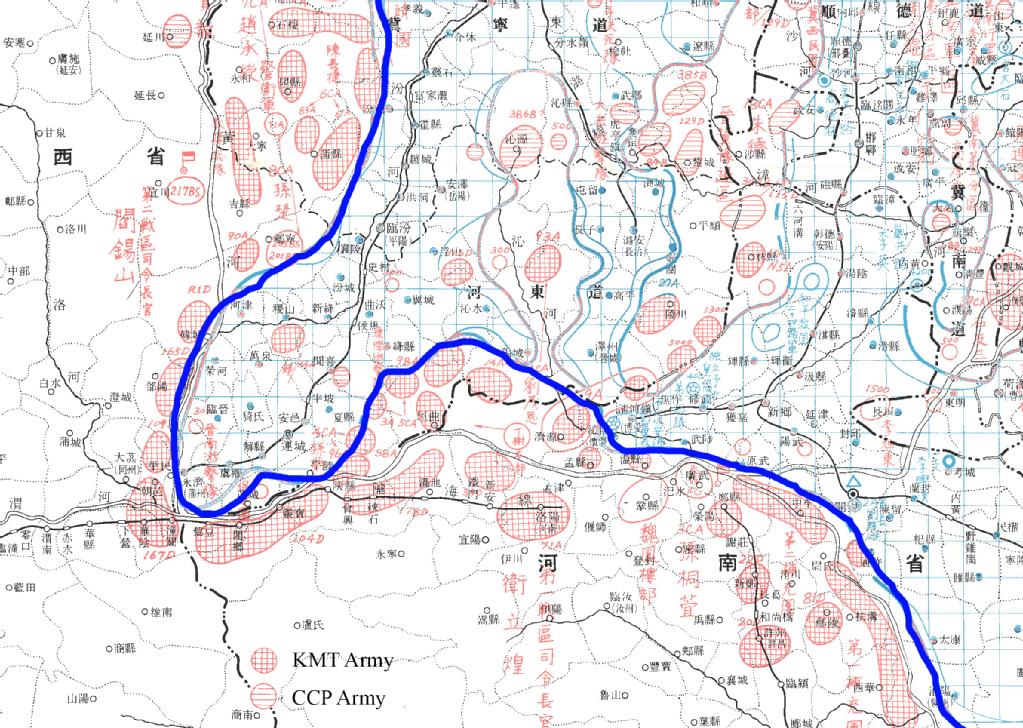

The Japanese met government-led KMT forces head on, swiftly taking territory in the North of China and pushing the KMT south. The CCP on the other hand, already diminished from confrontation with the KMT, was not directly confronted by the Japanese. From locations dotted across the country it led guerrilla resistance. As the Japanese advanced, many CCP strongholds were enveloped inside Japanese occupied territory.

Kung and Chen show that this unique position behind the enemy lines made a big difference to membership of the CCP. They analyse three measures to understand the growth in CCP membership in the period 1937–45: the density of CCP middle to upper rank officials, the density of CCP martyr soldiers and the number of soldiers living in a CCP guerrilla base in 1940.

They find membership of the CCP grew incredibly quickly in the first three years of the Sino–Japanese war, from 40,000 to 800,000 members. But this growth was particularly concentrated in areas inside occupied territory.

Figure 2: The boundary of Japanese occupied territory and the location of KMT and CCP groups

Nationalism and the rise of the CCP

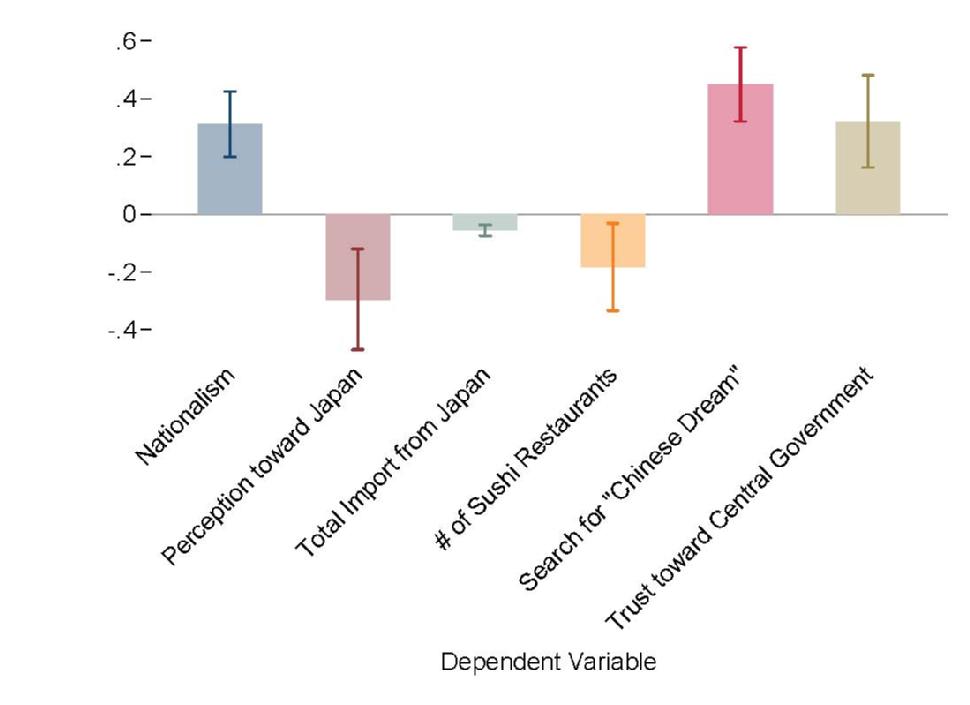

Kung and Chen suggest that the location of CCP forces in occupied territory created the context through which the CCP could win the support of the peasantry: by appealing to ideals of nationalism.

Nationalism had already gained interest among Chinese intellectuals after China’s defeat by the Japanese in 1894–5. It was an ideal Mao Zedong adopted throughout his political career. But before 1934, rural civilians were less engaged. For many poor peasants, day-to-day life was a more pressing concern than ideals of nationhood.

The Second Sino-Japanese war changed that. The shock of the invasion, and the fierce treatment of Chinese civilians by invading forces put rural civilians under new pressure. The situation made it easier for the CCP to promote Mao Zedong’s vision of nationalism: that the fate of the individual was bound up with the fate of the nation.

Kung and Chen’s data supports this theory. They find that the CCP gained strength in areas occupied by Japanese forces, which were suffering particularly from the effects of war. Significantly, war suffering (rape cases and deaths) had no effect on the rise of the CCP outside Japanese territory. This suggests that the presence of external Japanese forces made the CCP’s ideals of nationhood more appealing.

The effect of CCP local party building was stronger in Japanese-held territory too. The CCP has been characterised by many scholars as a group that was able to mobilise the people to support its anti-Japan cause. Kung and Chen’s data on the development of party groups, branches and committees shows that they were much more successful at mobilising the people within occupied territory.

The CCP also grew faster in areas governed by puppet troops. Having acquired a large territory in the North of China, the Japanese struggled to govern it effectively. They made use of 600,000 puppet troops (made up of KMT captive soldiers and remnants of local warlords) to maintain control. In occupied areas governed by these troops – where the invading army had a less forceful presence – the CCP grew rapidly. Interestingly, CCP growth was compromised in areas where the KMT was still present. It was the combination of invading forces and a dearth of other national parties that allowed the CCP to grow.

The persistence of Chinese nationalism

The results strongly suggest that the Japanese invasion of China offered the opportunity for the CCP to rise to power. The CCP’s nationalist sentiment and its ability to work within rural areas appealed to an embattled peasantry in occupied areas.

As a final test, Kung and Chen also consider the persistent effects of nationalism today. Taking data from six different attitude surveys collected across China, they find that nationalistic attitudes remain strongest in areas previously occupied by Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese war.

Figure 3: Nationalistic sentiment remains stronger in areas of China previously occupied by Japan

Find out more

The Crafts Lecture 2023, The Rise of the Chinese Communist Party, delivered by Professor James Kung (Hong Kong University): Watch here.

Kung, J., and Chen, T. (2023), The Rise of the Chinese Communist Party, working paper (SSRN).