2013(2) - Lander

Contents

1. The Discovery of Oyu Tolgoi: “Deposits of Strategic Interest” and Reform of the 1997 Minerals Law

2. The Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement

3. The Rubber Hits the Road for Oyu Tolgoi

4. 2012: The Year of the “Roaring Mouse”

5. In Between a Rock and a Hard Place? The Politics of Foreign Direct Investment and the Prospects for Diversification and Distribution

6. The Political Power of the “Resource Nationalism” Frame

7. Concluding Thoughts

Bibliography

A Critical Reflection on Oyu Tolgoi and the Risk of a Resource Trap in Mongolia: Troubling the “Resource Nationalism” Frame

Jennifer Lander

Abstract

Commonly depicted as one of the final frontiers, Mongolia has gained international notoriety since the turn of the millennium for the discovery of an extensive mineral resource base, estimated to hold over U.S. $1 trillion worth of mineral assets spread over 6000 sites (Campi, 2012). Mineral riches, however, have been shown to be as much a curse as a blessing for economic and social development (Auty, 2001; Humphreys et. al, 2007). Since the discovery of the Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold deposits in 2001, Mongolia has leap-frogged from a fairly low position on the mineral-dependence scale to being widely perceived as ‘especially vulnerable’ (Haglund, 2011) to the resource trap;[i] mineral exports comprised 89.2% of Mongolia’s total exports in 2011, up from 32.5% in 2000 (Mongolian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 2011). In the case of Mongolia, the lack of a significant industrial base and high levels of poverty in a sparsely populated landlocked country have triggered the red flags of a potential resource trap in both domestic and international development governance circles (Isakova et. al, 2012; World Growth, 2008; Moran, 2013; Reeves, 2011; Barma et al., 2011). This paper will engage with some of the complexity of Mongolia’s emergence as a mineral-exporting economy and the government’s negotiation of a potential resource trap through committing a sufficient portion of mineral rents to economic diversification and public redistribution. While it is impossible and unhelpful to draw any fast conclusions about the long-term implications of an extractive development strategy for Mongolia, this article purposes to trouble the simplistic frame of “resource nationalism” that has been attached to Mongolia’s governance of Oyu Tolgoi.

Keywords

Mongolia, Oyu Tolgoi, economic development, resource trap, politics, democracy, foreign direct investment, resource nationalism, rule of law

[i] Countries are considered mineral dependent when their mineral exports comprise 25% of the total of tangible exports. Mongolia has joined the DRC, Zambia and Papua New Guinea in the top twenty non-fuel mineral-dependent countries. See Haglund, 2011: 2-3.

Introduction

Oyu Tolgoi, Mongolia’s National Development Strategy and the Resource Trap Thesis

Mongolia is the least densely populated country in the world; 2.7 million people live in a landlocked land mass approximately the size of Western Europe, almost 1.6 million square kilometres. In the early 1990s, Mongolia experienced a remarkable post-communist transformation with the collapse of the Soviet Union. While space constrains a full discussion of the particularities of Mongolia’s transformation in the wake of the crumbling Soviet Union, scholars at the time observed with fascination its remarkable “success” in adopting the full range of reforms for democratisation and marketisation required by the country’s acceptance of financial assistance from international financial institutions (IFIs). Though there is not space to do so here, scholars have gone to great effort to understand this surprising[i] (Anderson et. al, 2000; Kopstein and Reilly, 2000; Fish, 1998; Fish, 2001; Fritz, 2008) embrace of market democracy, analysing the manner and circumstances in which the traits of liberal market democracies – multi-party elections (Bayantur, 2008; Rossabi, 2005), high rates of public participation in political processes (Sabloff, 2002; Sumaadii, 2012) the separation of powers (Ginsberg, 2003), a written constitution (Sanders, 1992; Fish, 1996; Bedeski, 2006), human rights commitments (Landman et. al, 2005), privatisation (Korsun and Murrell, 1995), financial and trade liberalisation (Pomfret, 2000; Rossabi, 2005), and an active civil society (Bedeski, 2006) – have come to characterise Mongolia. While some aspects of reform were implemented more thoroughly than others (Anderson et al., 2000), Mongolia’s transition has been widely perceived as an authentic process of democratisation and marketisation (Pomfret, 2000; Fritz, 2008) in contrast to its Central Asian neighbours who have settled in the ‘foggy zone’ (Schedler, 2002: 37 quoted in Bayantur, 2008: 6; Kopstein and Reilly, 2000) as post-Soviet autocracies, exhibiting the qualities of neither socialist authoritarianism nor capitalist democracy as classically defined.

One of the less successful – some would say catastrophic (Rossabi, 2005) – aspects of Mongolia’s transformation in the 1990s was the sharp decline in living standards: over a third of the population experienced a sudden plunge into abject poverty (Rossabi, 2005; Nixson and Walters, 2006; Sneath, 2003; UNDP, 2000; World Bank, 2006). Unfortunately, there has been no significant transformation in this area; a recent UNDP Human Development Report (2013: 5) states that ‘the intensity of deprivation – that is, the average percentage of deprivation experienced by people living in multi-dimensional poverty – in Mongolia was 41%.’ While Mongolia has never been considered a wealthy country, the communist government provided a strong safety net and high levels of education (Rossabi, 2005); social welfare comprised 40% of the communist government’s expenditure (ADB, 2008) and universal literacy had been achieved by the late 1980s. The economic shock of the collapsing Soviet Union and the sudden introduction of structural adjustment policies in the early 1990s through ‘shock therapy’ (Sachs, 1994; Klein, 2007) meant that real expenditure on health and education was reduced by 46% and 56% between 1990 and 1992 (Sneath, 2006: 149-150) and unemployment rose from 1.3% in 1989 to 20% in 1994 (World Bank, 1996; Rossabi, 2005). These statistics are really only scratching the surface in terms of indicating the social and economic upheaval experienced by Mongolians during the early 1990s, and in fact probably obscure the actual extent of change in social reality (Rossabi, 2005; Sneath, 2003). For example, the fact that 80% of the population are recorded as employed obscures the reality that the rural population doubled between 1990 and 1997 to comprise over a third of the total population and half of the working population as many urban Mongolians returned to herding to find subsistence in a contracting economy (Mearns, 2004). Thus, while the working population was recorded at 80%, half of this number was comprised of new herders seeking subsistence, which was a risky and precarious mode of employment in the transition years given the extensive deregulation of the pastoral economy (Mearns, 2004; Sneath, 2003; Upton 2010; Upton 2012).[ii]

Mongolia emerged from the 1990s with a highly liberalised, investment-oriented economy, a narrow industrial base and a scaled-back, uneven welfare distribution system (Nixson and Walters, 2006). While GDP growth was sluggish – hovering between 1-3% annually (World Bank Data, 2013) – and little progress had been made in terms of reducing poverty (UNDP, 2000), Mongolia was poised for investment into its natural resources in the early years of the new millennium. As Dierkes (2012: 3) argues, Mongolia’s proximity to the Chinese market, democratic governance structures and well-educated, young workforce, not to mention its liberal regulation of mining activities, made Mongolia’s natural resources an attractive prospect for mining companies. This external foreign interest coincided with the policy expectation that the exploitation of natural resources would be Mongolia’s main vehicle for development (Tumenbayer, 2002).

Consequently, from the perspective of the Mongolian government, the 2001 discovery of the extensive Oyu Tolgoi copper and gold deposits in the southern Gobi region signified a turning point in terms of the country’s role in the global economy in finding a natural resource base and, critically, an opportunity to finally shake the poverty that had shadowed the 1990s. In addition to the 2001 Southern Oyu discovery, three additional deposits were discovered (2002-2008) which comprise the current Oyu Tolgoi mining complex (Rio Tinto, 2013; Kohn and Humber, 2013). In addition to immense gold deposits,[iii] Oyu Tolgoi is now estimated to contain 46 billion pounds of copper, with additional inferred sources estimated at 55 billion pounds (Turquoise Hill Resource, 2013). The impact of the investment from the Oyu Tolgoi exploration was swift: the mineral sector’s share of GDP grew from 10% in 2002 to 33% in 2007 (Combellick-Bidney, 2012: 273). While it was no surprise that Mongolia had vast copper and gold reserves (Dierkes, 2012), the concentration of this mineral wealth within one mining area and under the auspices of one licensed company suggests that Oyu Tolgoi marked a turning point for Mongolia in terms of engaging with large-scale, long-term foreign investment (Macnamara, 2012). Oyu Tolgoi (“Turquoise Hill”) is now one of the world’s largest gold and copper mines, and its investment agreement is the largest in Mongolia’s history (Oyu Tolgoi LLC, 2013). Oyu Tolgoi is estimated by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to boost Mongolia’s GDP by 35% by 2021 with over U.S. $6.2 billion invested between 2006 and 2013 in the first phase of construction (Rio Tinto, 2013). The operational life of the mine is projected to be at least 59 years (Fisher et al., 2011: 20), which has the potential to dramatically affect Mongolia’s long-term economic trajectory.

The introduction of a new development strategy in 2007 – the ‘MDG-Based Comprehensive Development Strategy for Mongolia 2007-2021’ (NDS) – reflects the heightened development aspirations inspired by the discovery of Oyu Tolgoi. The NDS heightens the expectations of development from the 1990s to the ambitious goal of achieving the status of a middle-income country with an industrialised knowledge-based economy, and a high standard of human development based on the MDGs by 2021 (Mongolia, 2007). The language of the NDS, however, does not simply reflect the rhetoric of the international MDG development agenda; its vision is linked from the outset of the document to the increased capacity of the Mongolian economy in light of ‘mineral deposits of strategic importance,’ (Mongolia, 2007: 5) a catch-phrase associated with the discovery of Oyu Tolgoi. The NDS contains a clear policy shift with specific development targets to undergird these heightened aspirations, evidently based on optimistic forecasts for economic performance.

For example, the first and second priority areas (Mongolia, 2007: 5) to 1.) ‘provide for all-round development of the Mongolian people’ and 2.) ‘intensively develop export-oriented, private sector-led, high technology-driven manufacturing and services to create a sustainable, knowledge-based economy’ relies upon the critical third: to ‘exploit mineral deposits of strategic importance, generate and accumulate savings, ensure intensive and high economic growth, and develop modern processing industry.’ The priorities of the NDS and the goal of achieving middle-income country status by 2021 – notably the year Oyu Tolgoi is expected to reach full production (Rio Tinto, 2013) – would seem exaggerated unless the Mongolian government had reason to believe that the profits of resource extraction would be sufficient to diversify the economy and dramatically improve social welfare across the entire population. While the NDS suggests an optimistic sense of the development opportunity of mineral exploitation for Mongolia, the priorities placed upon economic diversification and effective distribution also suggests that Mongolia’s leaders recognised the serious risks associated with development strategies based on mineral extraction.

The “resource trap” is a widely recognised thesis in development literature that problematises the puzzle of ‘skewed economies’ and public impoverishment in many countries with extensive natural wealth (Collier, 2007; Humphreys et al., 2007; Auty, 2000; Auty, 2001; Bebbington et al., 2008; Rosser, 2006). The signs of a country at risk of a resource trap are exhibited in an impeded inability, known as Dutch Disease, to invest in other economic sectors beyond primary extraction, particularly in value-adding secondary sectors such as manufacturing or processing (Humphreys et al., 2007). The risk of overspecializing in one industry or commodity sector at the expense of others is heightened because the quantity of resource revenues combined with the timing of the earnings can lead to income volatility (Humphreys et al., 2007: 6). Income volatility, according to Humphreys et. al (2007: 6), is due to three distinct problems associated with extractive industries: ‘the variation over time in rates of extraction, the variability in the timing of payments by corporations to states, and fluctuations in the value of the natural resource produced.’ The national income volatility that results from impeded diversification tends to have a correlative impact on distribution. As Bebbington et al. (2008: 888) points out, ‘mining has [been] associated with spectacularly unequal distributions of wealth.’ Unless a country has very rigorous transparency policies in place, mineral rents have been shown to be very amenable to elite capture (Auty and de Soysa, 2005). However, the distribution of wealth is not simply a question of corruption. It is difficult for governments, particularly those laden with debt, to make long-term human development or welfare commitments because of the boom-and-bust cycle of commodity value and income (Humphreys et al., 2007: 8; Frankel, 2010). The revenues gained from “boom” periods often disappear in the short-term to finance the “bust” phase of the cycle, particularly in cases where further debt obligations are incurred on expenditures made in the boom phase (Frankel, 2010). This vicious cycle has been shown to lead to declining social spending and rising inequality with a knock-on impact on democracy, as the inability of the state to fulfil its promises tends to erode public trust in the efficacy of government (Stiglitz, 2007; Auty and de Soysa, 2005).

The author will use the resource trap thesis as the starting point for the following analysis because it highlights the tension between opportunity and risk underlying any economic development strategy based on mineral extraction. The macroeconomic challenges of diversification and distribution, then, can be appropriately understood within the particulars of the Mongolian context. The author hopes that this piece will aid in the illumination of Mongolia’s governance of Oyu Tolgoi, considering both the government’s commitments to its public and the role of international finance and investment into the project.

1. The Discovery of Oyu Tolgoi: “Deposits of Strategic Interest” and Reform of the 1997 Minerals Law

The Oyu Tolgoi deposits were discovered under the provisions of the 1997 Minerals Law, which incentivised foreign direct investment (FDI) into Mongolia’s mining sector by establishing low barriers to prospecting, exploring and mining for minerals (Tumenbayer, 2002: 5; World Bank, 2005; Sukhbaatar, 2012: 139). The 1997 Minerals Law had a ‘high positive profile’ (World Growth, 2009: 5-6) with foreign and domestic investors; a World Growth (2009: 5-6) report states that ‘mineral exploration increased five-fold between 2001 and 2006’ as a direct result of Mongolia’s legal framework which was apparently almost on par with ‘international best practice,’ with favourable tax and royalty rates. It guaranteed the investing company a stability agreement with the government so that changes in national law regarding tax rates or royalty regimes would not affect their investment (Sukhbaatar, 2012: 139). Additionally, the 1997 Minerals Law stipulated that the state could not participate directly as a stakeholder in mining or exploration. The license-holder had many rights and few obligations: it had the right to gain any number of further licenses, sell its products at international prices on both domestic and international markets, as well as having “right of way” through adjacent land in use or owned by others (1997 Minerals Law, Articles 13 and 16).

Proponents of FDI-lead economic development strongly suggest that the benefits of Oyu Tolgoi would have been far larger had the 1997 Minerals Law remained unchanged and the 2004 stability agreement between Ivanhoe Mines and the Mongolian government kept intact (World Growth, 2009: 8-9). The Mongolian government, however, decided that the Oyu Tolgoi was a ‘mineral deposit of strategic importance’ (Mongolia, 2006)[iv] and accordingly adjusted the 1997 Minerals Law in 2006 in order to negotiate for a specific Oyu Tolgoi investment agreement (OTIA, Article 5.4).

2006 marked a turning point for Mongolia’s engagement with investment into its mineral sector. The 1997 Minerals Law was amended in July 2006 to give the Mongolian government greater influence in the negotiation of mining investment agreements by permitting the government to hold a direct stake – up to 34% - in ‘nationally strategic deposits.’ The 2006 reforms enabled the government to seek an individual investment agreement with an investor, where more conditions could be placed upon the investment than under the former stability agreement model (Mongolia, 2006). Additionally, a Windfall Profits tax was introduced in May 2006 to reap increased revenue when market prices exceeded certain limits. Both the Windfall Profits tax and the amendments to the Minerals Law were popular among the Mongolian public, following widespread concern over land rights and long-term leases for foreign mining companies and in particular, Ivanhoe Mines.[v] According to Sukhbaatar (2012), the public pressure on the government in early 2006 was mainly concentrated on changing the law so that the state could have a greater advantage in large-scale mining projects and demanding greater distribution of mining revenue to the public. It is interesting to note the 2006 shifts in legal regulation which preceded the introduction of the ambitious NDS in 2007. Rather than relying on a relatively unregulated market economy to spontaneously catalyse economic development, the NDS articulates an aspiration for a more rigorous regulatory framework for large-scale mining investment in order to capture the most revenue for Mongolia to diversify its economy, increase welfare expenditure and repay the high level of national debt (Mongolia, 2007).

While these changes received support from Mongolian citizens and civil society, , investors and the broader financial community strongly criticised these legislative manoeuvres as indicative of a trend towards resource nationalism (Packard and Khurelbold, 2010). The ‘protectionist’ (Adams, 2012: 4) adjustments to the Minerals Law and the introduction of the Windfall Profits tax in 2006 were perceived as a part of a renationalisation of Mongolia’s mining sector (Sukhbaatar, 2012; Macnamara, 2012). In particular, the Windfall Profits Tax was seen to undermine the stability of the rule of law in Mongolia (Sukhbaatar, 2012). This perspective reflects a particular liberal conception of the rule of law (Jayasuriya, 1999: 2) where the strengthening of the rule of law is correlated with the ‘weakening of governmental or public power.’ Despite heated opinions on both sides on the controversial Windfall Profits Tax, Sukhbaatar (2012: 142) argues that ‘it is difficult to pass judgment on the tax law,’ given that the requirements of the rule of law – ie, generality, public knowledge, prospective application – were fulfilled and Mongolia was technically using its sovereign prerogative to determine its taxation framework, a view that was affirmed in a United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) arbitration tribunal between a Russian mining company and Mongolia (Usoskin, 2011). Sukhbaatar critically notes that the point of contention lies in the policy, rather than legal, perspective: ‘Mongolia may have hurt its reputation among foreign investors by succumbing to short-term gains from temporary commodity price increases’ (Sukhbaatar, 2012: 142). The revised Minerals Law passed in July 2006 was less controversial, particularly from the view of investors, because it still provided a long-term, stable framework for investment agreements despite reneging on some of the more liberal provisions of the 1997 law (Sukhbaatar, 2012).[vi]

2. The Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement

In October 2009, after five years of negotiations, the Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement (OTIA) was signed by the Mongolian government, Rio Tinto and Ivanhoe Mines (now Turquoise Hill Resources). The Mongolian government emerged with a 34% stake, giving it three seats on the governing board of Oyu Tolgoi LLC. It determined stabilised tax rates and a zero rate for Value-Added Tax (VAT) for specified goods and services related to Oyu Tolgoi, in addition to the freedom of the foreign investor to repatriate export earnings (OTIA, Articles 2.1 and 2.18). It also gave the foreign investor the rights to avail itself of lower tax rates if they existed in applicable international or double-taxation treaties (OTIA, Article 2.2.7). In turn the foreign investor committed to a range of initiatives to ‘support socio-economic development policies...to ensure that sustainable benefits from the OT Project reach Mongolian people, including people in Umnogovi aimag’ (OTIA, Article 4.5).

The social provisions set out in Chapter Four of the OTIA particularly place a large proportion of onus directly upon the investor to guarantee local and regional opportunities, particularly in Umnogovi aimag, consistent with the goals of NDS to reduce rural-urban inequalities and create thriving townships around Oyu Tolgoi. As part of the agreement, the Investor further committed to contribute U.S. $126 million (Rio Tinto, 2013) for a five-year training and education project, in addition to showing preference for Mongolian employees. The OTIA also requires that the power for Oyu Tolgoi be sourced from Mongolia after five years of operation, and any smelter for processing the extracted metal is to be located domestically as well. The terms of the OTIA seem to indicate that the Mongolian government strategically used its 34% stake in the deposits to negotiate an agreement that goes beyond revenue accumulation; the OTIA requires that the principal Investors actively assist in diversifying Mongolia’s economy, as well as provide socio-economic development opportunities and benefits for Mongolian citizens.

Joseph Stiglitz (2007), an influential economist, has cautioned countries with natural resources to make sure they have a strong institutional framework in place before commencing resource exploitation, because of the risks to diversification and distribution associated with income volatility. While the exploitation of Oyu Tolgoi was already underway, Mongolia made significant progress after signing the OTIA in terms of establishing the appropriate institutions to enable diversification and equitable distribution. In November 2009, the Human Development Fund (HDF) replaced the Mongolian Development Fund (est. 2007) ‘to counteract rising inequality and distribute the benefits of the mining boom more broadly’ (OTIA, 2009: 10). The state is supposed to allocate a portion of revenue to the HDF each year based on expected earnings from mineral dividends, royalties and taxation (OTIA, 2009; Campi, 2012). It was primarily designed as an ongoing ‘cash transfer mechanism,’ (Campi 2012; Moran, 2013) in addition to funding education initiatives and social services. According to Campi (2013), the HDF was a legal milestone for the Mongolian public, as it enshrined ‘equal eligibility’ for each citizen to share in the country’s mineral wealth.

To generate savings and prevent reliance on volatile mineral prices, the Mongolian Parliament passed the Fiscal Stability Law in 2010 and the Integrated Budget Law in 2011 (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013; Isakova et al., 2012). These laws have the combined effect of capping the deficit and public debt at 2% and 40% of GDP respectively, keeping expenditure in line with the growth rate of Mongolia’s non-mineral GDP, and constraining the power of parliament to influence the state budget (Ognon, 2013). Notably, the 40% cap on public debt only starts in 2014 (Ognon, 2013). According to an EBRD working paper, the Fiscal Stability Law crucially included the introduction of a ‘transparent formula for copper price projections’ (Isakova et al., 2012: 15) to help the Mongolian government anticipate the boom and bust cycle of this commodity market. Finally, the Fiscal Stability Law established the Fiscal Stability Fund (FSF) to accumulate ‘excess commodity-related revenues’ (Isakova et al., 2012) from boom phases in order to supplement financial losses experienced in bust phases of the cycle.

In its recommendations to Mongolia, the EBRD (Isakova et al., 2012: 15) has strongly advised that fiscal frameworks designed to capture maximum revenue from natural resource exploitation are ‘arguably the most critical weapon’ to defend against the resource trap. The passing of budgetary and fiscal laws in conjunction with establishment of the Human Development Fund and the Fiscal Stability Fund suggests that the Mongolian government is serious in taking the institutional and legal steps necessary to side-step a resource trap, following the general consensus that institutional strength is key to its prevention (Humphreys et al, 2007; Stiglitz, 2007; IMF, 2012; World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013). Both IMF and the World Bank advisors have praised the efforts of the Mongolian government in relation to its institutions (World Bank Mongolia 2013; IMF 2013), while urging for ongoing improvement in this area. The question remains, however, if institutional strengthening and legal frameworks are sufficient to prevent a resource trap. There are two critical factors to consider. Firstly, what exactly are the financial obligations of the Mongolian government in regard to its 34% stake in Oyu Tolgoi? Secondly, and relatedly, how viable is Mongolia’s fiscal stability framework given these obligations, its debt burden and the volatility of mineral prices?

3. The Rubber Hits the Road for Oyu Tolgoi

In addition to emphasising the importance of institutional strength, Stiglitz (2007) goes on to warn governments against entering into complex contracts with foreign investors whose bottom-line, as expected, is profit. The basic assumption of the Comprehensive National Development Strategy (NDS) is that the exploitation of natural resources in the short-term will produce enough savings for Mongolia to reach middle-income country status by 2021, the same year that Oyu Tolgoi is supposed to reach full production (Rio Tinto, 2013). Is this assumption realistic? The government has stressed to the public that the private stakeholders are internalising the fiscal risk of the project; the Minister of Finance, S. Bayartsogt, stated in a televised public debate on the OTIA that ‘Mongolia acquired 34% equity free of charge... Mongolia has made a very good bargain’ (Mongolian Mining Journal, 14th November 2011). However, one of the less understood complexities of the OTIA is that the Mongolian government is actually required to finance its 34% stake in the mine (White, 2013), taking financial responsibility alongside Turquoise Hill Resources and Rio Tinto for all expenditures. If it is unable to invest its own capital, the Mongolian government has the “flexibility” to fund its equity share by accepting a loan from the private stakeholders (White, 2013). However, there is a catch: as a common – vs. preferred – stakeholder, the Mongolian government has to settle its debt obligations before it can recoup profits.[vii] Mongolia accepted a loan from Rio Tinto, expecting dividends from the mine to begin in 2019 in addition to royalty and taxation revenue in the meantime (Zand, 2013).

Given these financial obligations, the Mongolian government expressed deep concern in 2013 over the alleged U.S. $2 billion in cost overruns incurred by Rio Tinto (Riseborough and Kohn, 2013), which threatens to seriously delay the expected flow of dividends from the mine. A recent article quoted the Head of Planning at the Mining Ministry as estimating that it will be twenty or thirty years before Mongolia shares the profits of Oyu Tolgoi (Zand, 2013; see also Kohn and Mellor, 2013). The Mongolian government halted the first shipments of copper in June 2013 over its ’22 Points of Dispute’ (Els, 2013) with Rio Tinto; the World Bank has advised that any further delays will have ‘significant adverse impacts’ (World Bank Group – Mongolia, 2013: 8) on Mongolia’s foreseeable economic growth. Also of concern to the government is the U.S. $5.1 billion financing package required for the second phase of mine construction (Riseborough and Kohn, 2013), where 80% of the mineral resource lies (Rio Tinto, 2013). These concerns regarding cost over-runs and further financing pose substantial challenges for Mongolia’s budget and debt burden, and crucially, the viability of its fiscal stabilisation framework designed to capture revenue for diversification and distribution.

The little-known complexity of Mongolia’s financing obligations has the potential to undermine Mongolia’s fiscal stability framework. Critically, it is important to determine to what extent Mongolia’s trending pattern of fiscal spending is symptomatic of institutional failure or the conditions of the OTIA itself. The condition of “debt repayment before dividends” incentivises Mongolia to assume more debt in the short-term to fund the infrastructure and construction costs required by the project in order to make it profitable more quickly (White, 2013; World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013). Given the location of Oyu Tolgoi in the Gobi desert, transport and energy infrastructure [see Map 1] are urgently needed but costs are high. While it seems positive that Mongolia can fund its equity stake in the project by investing in infrastructure which will hopefully have diversification benefits, Mongolia could still easily spiral into a resource trap if the government gets into the cycle of overspending on the basis of anticipated profits (White, 2013).

Map 1: Transport/Industrial Infrastructure (sourced from Turquoise Hill, 2013)

When the boom in global copper prices coincided with the Fiscal Stability Law in 2010, the government expanded its expenditure far above the stipulated 2% GDP deficit ceiling. While the Fiscal Stability Fund did generate capital from 2011-2012 due to high commodity prices and significant investment flows (Isakova et al., 2012), its U.S. $300 million asset stock was a fraction of the revenue needed to expand infrastructure. For example, the rail infrastructure required to export mineral ore to Russia and China is estimated to cost U.S. $3 billion (Isakova et al., 2012: 10). Unfortunately, it seems that Mongolia has succumbed to a ‘pro-cyclical’ (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013: 5) model of expenditure to uphold its equity obligations through investing in large infrastructure projects, as evidenced by the public debt incurred through the Development Bank of Mongolia (DBM) and the Chinggis Bond.

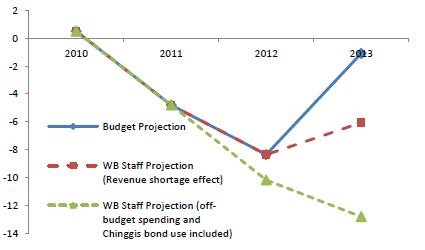

In 2011, the Mongolian government established the DBM through law ‘with a mandate to finance development projects’ (Isakova et al., 2012: 9). Parallel to the establishment of the fiscal stabilisation fund designed to store savings, the Mongolian government acquired significant debt through the DBM; the interest on these bonds was U.S. $15 million in 2012 alone. The EBRD has cautioned the government to clarify the relationship between the MDB and the fiscal stability framework: it ‘creates an effective loophole...[that] allows the government to build up contingent liabilities that could offset accumulation of the FSF’ (Isakova et al., 2012: 9). These concerns have not been addressed and the government has continued to acquire more debt through innovative means, as concessional loans from international donor agencies are being gradually phased out.[viii] For example, in November 2012 Mongolia sold its first government bond, worth U.S. $1.5 billion in debt, on the international bond market to fund energy infrastructure and the Millennium Road project (Frangos and Natarajan, 2012). The recorded deficit in 2012 was the highest in thirteen years at 8.4% of GDP; the World Bank estimates that the addition of Mongolia’s accumulated debt through the DBM and the Chinggis bond could extend the total fiscal deficit to 13% (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013: 4). [See Graph 1]

Graph 1: Fiscal Deficit Projection (% of GDP) (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013)

It seems that Mongolia’s fiscal stabilisation framework, despite looking quite effective on paper, is impaired in practice because it goes against the grain of the OTIA incentive structure. In order for Mongolia to reap dividends from Oyu Tolgoi, both infrastructure investment and debt repayment are necessary. Given Mongolia’s debt obligations, this two-fold requirement begs the question as to whether stronger fiscal management is powerful enough for Mongolia to realise the profits of its 34% equity share, even in the long-term.

4. 2012: The Year of the “Roaring Mouse”[ix]

The copper price “bust” in 2012 brought the implications of the OTIA’s fine-print home to roost for Mongolia, resulting in the introduction of the Strategic Entities Foreign Investment Law (SEFIL) in June 2012. Under SEFIL the Mongolian government attempted to renegotiate the OTIA (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013). Not only did Rio Tinto and Turquoise Hill reject this proposal, but it caused a 17% collapse in foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2012 which spiralled to a 49% drop in 2013 (Els, 2013). Unfortunately for Mongolia, contract renegotiation was a red flag to other potential investors, and has significantly affected the perception of Mongolia as a “stable” destination for FDI. According to the World Bank, the loss of FDI is deeply significant for the productivity of the economy as it has been Mongolia’s main source of private investment in the past two years (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013). In 2012, total revenue accumulated was 12.1% below the budget projection, with mineral revenue 35.6% below the previous year; total exports fell by 9% (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013: 4). Mongolia still experienced double-digit GDP growth in 2012 at 12.3%, but it is significantly less than the 17% boom “high” in 2011 (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013: 8).

While renegotiation of the OTIA was unsuccessful, the Mongolian government continued to challenge Rio Tinto through allegations of tax evasion. A recent report published by the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) suggests that Mongolia may be missing out on substantial tax revenue from Oyu Tolgoi. Rio Tinto maintains that U.S. $1.1 billion has been paid to the Mongolian government in taxes, fees and royalties (Rio Tinto, 2013), but the current debate centres specifically on the amount of withholding tax that should have been paid to the Mongolian government. According to the terms of the OTIA, a 20% withholding tax is supposed to be levied on dividends from the mine (Deutsch and Edwards, 2013). Drawing on the SOMO findings, a recent Reuters article (Deutsch and Edwards, 2013) argues that significant tax has not been paid, meaning that Mongolia could be missing out on billions of dollars in tax revenue. The Dutch holding company for Turquoise Hill subjects revenues from Oyu Tolgoi to a double-taxation treaty signed by Mongolia and the Netherlands in 2004. The article states that this treaty enables ‘Dutch-registered firms to channel income from dividends, royalties and interest earned in Mongolia through their Dutch company, so paying no withholding tax.’ As the Netherlands is infamous as a tax evasion location for multinational corporations (McGauran, 2013), Mongolia cancelled its double taxation treaty in September 2012 after its requests for amendments to the double-taxation treaty were refused by the Netherlands.[x] Rio Tinto maintains that this action will make no difference to ‘Oyu Tolgoi LLC’s use of the Dutch company’ or to its future tax payments, as the OTIA included the stabilization of all tax treaties current at the time of signing in 2009 (Deutsch and Edwards, 2013). While the Mongolian government is evidently taking bold steps to challenge tax evasion, it does cast a shadow of doubt over the common reassurance from analysts that tax revenues will be sufficient to counteract the effect of rising public debt (Frangos and Natarajan, 2012).

5. In Between a Rock and a Hard Place? The Politics of Foreign Direct Investment and the Prospects for Diversification and Distribution

Given the complexity of putting ambitious policy on revenue accumulation into practice with Oyu Tolgoi, it is not too surprising that the economic diversification and welfare distribution expected from the project has been fairly disappointing so far. Manufacturing and construction has increased somewhat but due largely to a slump in commodity prices; the manufacturing industry as a percentage of GDP rose from 4% in 2009 to approximately 12% in 2012 (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013).[xi] The long-term success of diversification depends upon the sustainability of its funding, which is considered low by fiscal experts given the scale of infrastructure required (Moody’s Investor Services, 2013).

The 2012 “bust” in commodity prices decreased public expenditure from the HDF by 66% in 2013 (Ognon, 2013), with spending on education dropping from 14.6% of GDP in 2009 to 11.9% in 2011 (World Bank data, 2013). Inequality has continued to rise from the 1998 level to 0.365 on the Gini co-efficient (World Bank data, 2013). In light of bigger questions about the profitability of Oyu Tolgoi, the obligations in the OTIA on the foreign investors to contribute to Mongolia’s diversification and distribution seem negligible. If Mongolia continues to be afflicted by the symptoms of the resource trap in terms of its inability to collect or save sufficient revenue, 150 scholarships, support for small business and preferential employment for rural Mongolians will not be enough to achieve middle-income country status by 2021. In fact, the Mongolian government and civil society actors have recently accused Rio Tinto of reneging on its commitments in terms of the number of Mongolians employed in the mine, in addition to other concerns of over-spending and tax evasion (Stewart, 2013; Dugersuren, 2013).

The plummeting level of foreign direct investment into Mongolia’s mineral sector between 2011 and 2013 reflects a real perception among investors that the Mongolian government has succumbed to the temptation of protectionism, the antithesis of the values of free trade theory, which prioritise market efficiency and the rule of law to protect contracts. While issues with other mining projects have also contributed (Els, 2013), the renegotiation of the OTIA and the halting of Oyu Tolgoi’s inaugural shipments of copper over allegations of tax evasion seriously compromised Mongolia’s reputation as a ‘safe’ destination for investment, reflected in the drop in FDI that occurred between 2011 and 2012. As Oyu Tolgoi has a particularly high profile because of the involvement of Rio Tinto, a leading multinational mining corporation, Mongolia’s negotiation of this particular project sets an important precedent for other interested investors. The negotiations leading up to the OTIA and the shifting approaches to the regulation of foreign investment in the minerals sector since 2001 has cast Oyu Tolgoi as the ‘litmus test’ (Falconer, 2013) for other investors.

Institutions of investment and global development governance have adopted a similar perception as investors in terms of focusing on the strength of Mongolia’s institutions, reinforcing the “resource nationalist” image of the Mongolian government’s management of its mineral sector (Moody’s Investor Services, 2013; Adams, 2012). The global governance focus on Mongolia has zeroed in on its institutional reforms and political system (World Bank, 2004; Isakova et al., 2012; World Bank Group Mongolia 2013); the terms and implementation of the OTIA itself, now that it is signed, do not feature widely in global governance reflections upon Mongolia’s anxiety about a resource trap as an emerging rentier economy. For example, the decision of the Mongolian government to delay Oyu Tolgoi’s first copper exports in June 2013 was criticised by Moody’s Investor Service as it ‘“lowers investor confidence and underscores institutional weaknesses” in Mongolia’ (Moody’s Investor Services quoted in The Economist, 2013; Moody’s Investor Services, 2013).

6. The Political Power of the “Resource Nationalism” Frame

The perception of resource nationalism and weak institutions is only one way of thinking about the Mongolian government’s actions in relation to Oyu Tolgoi. Accusations of “resource nationalism” fail to take seriously the potential legitimacy of the Mongolian government’s concerns that the Oyu Tolgoi project, in practice, may not meet expectations for economic development. While Mongolia has adjusted its legal frameworks since the discovery of Oyu Tolgoi this is not necessarily a sign that the government does not take the rule of law seriously, remembering Jayasuriya’s problematisation of narrow definitions of the rule of law which insist on a negative relationship between the rule of law and governmental regulation (Jayasuriya, 1999).

Another way of framing the issue is to appreciate that the original 1997 Minerals Law reflected the neoliberal legal imagination of Mongolia’s post-communist transition (Rossabi, 2005; Ohnesorge, 2007; Bridge, 2004: 407). The inter-connected convergence of the disintegration of the Soviet Union with the Washington Consensus led to an ‘energetic neoliberalism’ (Ohnesorge, 2007: 243), which inspired a ‘substantive concern for free markets and limited government’ (Ohnesorge, 2007: 244) among policy advisors to countries emerging out of communism. This substantive[xii] turn is characterised by the need ‘to provide clear, predictable “rules of the game” within which private economic activity [could] take place’ (Ohnesorge, 2007: 247). As Sneath (2003: 441-442) argues, this was perceived by transition advisors as critical to ‘”emancipate the economy from the political structure, and allow it to assume its latent “natural” form, composed of private property and the market.’ This approach has been rigorously critiqued since the end of the 1990s for ignoring the social impact of economic reforms in terms of poverty and the role of effective government regulation in preventing economic exploitation (Fritz, 2002: 75-76; Rossabi, 2005; Nixson and Walters, 2006; UNDP, 2000; IMF, 2003). The recognised risks of a resource trap, the known dangers of corporate exploitation of developing countries’ natural resources and the established necessity of accumulating and using resource revenues for diversification and distribution all suggest that it is possible that Mongolia’s “re-regulation” of its mining sector following the discovery of Oyu Tolgoi has some legitimacy from a national development point of view. Even the former chief executive of Rio Tinto’s Oyu Tolgoi operations acknowledged that governments do have a regulative role in ‘making sure that businesses [meet] the standards the government desires for its country’ (McRae quoted in Bowler, BBC, 2013).

Furthermore, while “resource nationalism” suggests misplaced government priorities, the willingness of the government to risk renegotiation of the OTIA and foreign direct investment could also be conceived as reflecting genuine responsiveness to the concerns of its domestic constituency. Mongolian NGOs, such as Oyu Tolgoi Watch, have urged the government to regain ‘balance’ (Dugersuren, Mongolian Mining Journal, 2012), arguing that the OTIA is in favour of the foreign investor’s interests. Campi (2012) argues that ‘all stakeholders, including the countryside and urban poor, have actively expressed their opinions via workshops, community groups, environmental protests, and in the vibrant Mongolian press.’ While there is evidence that political parties have used the redistribution of mineral rents to court the public vote (IMF, 2012: 16), the establishment of the Citizens’ Hall in December 2009 following the signing of the OTIA, indicates there is at least some political will to engage in direct and deliberative democratic process with citizen concerns. Pomfret (2010: 155), a prominent scholar of Mongolia’s democracy, argues that while ‘Mongolia’s democracy can look chaotic, corrupt and incompetent when placed under a spotlight...in the big picture of economic policy, the democratic process has produced a consistent development strategy... in response to the will of the electorate.’

Thus it is worth noting that while populist electoral politics have been widely critiqued (IMF, 2013; Thomson Reuters, 2011; Walker, 2013; Gillies, 2010), the close attention and potentially high level of implicit political pressure upon Mongolia’s parliamentary and presidential electoral outcomes from foreign investors has yet to be problematised (The Economist, 2013; Pistilli, 2012). For example, a recent article in the Economist (The Economist, 2013) states that ‘hopes run high that the Democratic Party’s victory will put an end to political squabbling over such projects [in reference to Oyu Tolgoi]... a new foreign-investment law has long been stalled.’ The article quotes incumbent President Elbegdorj, who was re-elected to the ‘relief’ of foreign investors, as promising that ‘in the coming autumn session of parliament, I hope you will have that law.’ The language of “political squabbling” suggests a low view of Mongolian democracy; furthermore, the response of the President to the “hopes” of foreign investors conveys the reality of a political competition between the agendas of significant portions of the domestic constituency and investors. While there is insufficient space to explore this tension here, the constitutional legitimacy of this political reality is an important question for Mongolia to discern in coming years.

Significantly, in November 2013, the Mongolian parliament passed a revised Foreign Investment Law, which replaces the 1993 version of the law and SEFIL. The provisions of the new Foreign Investment Law signal a return, and also an expansion, of Mongolia’s post-communist commitment to ‘international best practice’ (World Growth, 2009) when it comes to the treatment of FDI. Foreign and domestic investors are given the same treatment under the new law, taxation rates are stabilised, a wider range of tax and non-tax incentives are available to investors, and the government’s involvement is restricted. For example, foreign investment is not subject to approval requirements in what were previously considered nationally strategic areas under SEFIL; only foreign companies that are over 50% state-owned and investing at least 33% into minerals, communication or financial sectors – the former ‘strategic’ sectors – must go through a government approval process (Hogan Lovells, 2013). The 2013 revisions to the Foreign Investment Law, which require a two thirds majority in parliament to overturn, are obviously intended to return confidence and stability to Mongolia’s investment climate (Diana, 2013; Hogan Lovells, 2013; Kohn, 2013). The scope of the revisions and the associated scrapping of SEFIL reflect an underlying economic need to reassure investors that laws governing investment will be protected to a greater extent from domestic politics.

7. Concluding Thoughts

This article has purposed to introduce the dilemma and opportunity of Oyu Tolgoi considering the political balancing act of development priorities and foreign direct investment which the Mongolian government has to navigate. Unfortunately, this is no playground see-saw in light of the real risks of a resource trap. Sustained investment in infrastructure, the expansion of secondary economic industry such as manufacturing and the equitable distribution of mineral wealth remain critical to avoiding the skewing effects of mineral dependence on economic diversification and equitable distribution. While Rio Tinto maintains that the project will be profitable in the long-run (Kohn, 2012), there are basic but lingering questions as to who will profit the most, when Mongolia can expect to make substantial profits and how much these profits will be worth in light of Mongolia’s high levels of debt and trending pattern of pro-cyclical spending. It is impossible to make any hard and fast conclusions about Mongolia’s emergence as a resource rich economy, given that Mongolia is very much in the midst of negotiating the terms of its transformation. However, the research presented in this article strongly suggests reconsideration of the current emphasis on treating Mongolia’s potential resource trap and the government’s navigation thereof as primarily symptomatic of “resource nationalism” and weak domestic institutions. Despite the cautionary advice of the World Bank to spend well rather than fast (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013), the Mongolian government is in between a rock and a hard place, considering the urgent and large-scale infrastructural needs of Oyu Tolgoi. Problematising domestic politics and institutions without regard for the global political economy of foreign direct investment dangerously depoliticises and simplifies the complex implications of Oyu Tolgoi for Mongolia’s development.

In this article, the author firstly delineated the development opportunity that Oyu Tolgoi posed for Mongolia following the socio-economic difficulties experienced during the 1990s. The discovery of the Oyu Tolgoi deposits in 2001 prompted a noticeable shift in Mongolia’s national development strategy based on heightened expectations of government revenue from the project. Notably, the NDS also contains commitments to diversifying Mongolia’s industrial base and spreading the wealth derived from mineral extraction in an equitable manner to lift the country out of poverty. It seems that the Mongolia government recognised the importance of diversification and equitable distribution to prevent the potential trap of mineral dependence, reflected in the obligations placed upon the foreign investor in the OTIA to contribute to these goals and the introduction of institutions to save revenue. Most importantly, it is clear that Mongolia took up the challenge of revamping and reorienting its institutional and legal governance of the mineral sector to enable the country to maximise the opportunity of Oyu Tolgoi for long-term development. It is worth mentioning that these governance initiatives are no mean feat for the government, given that the regulation of the mineral sector had been seriously scaled back and mineral exploitation emphasised at the expense of diversification in the 1990s.

The second half of the article featured a discussion of the key challenges facing the Mongolian government in terms of maximising its revenues from Oyu Tolgoi and creating a fiscal stabilisation framework to sustain infrastructure and welfare investments through volatile commodity price swings. Mongolia’s financial obligations as a stakeholder in Oyu Tolgoi were linked to the Mongolian government’s pattern of pro-cyclical fiscal spending and rising debt levels. Given that Mongolia can only gain dividends from Oyu Tolgoi once its debt has been repaid to Rio Tinto, the Mongolian government has become increasingly concerned about cost overruns incurred by Rio Tinto and the U.S. $5.1 billion required to finance the second phase of the mine. While it is too late to renegotiate the OTIA, the Mongolian government took action to protect taxation revenues from alleged evasion and attempted to delay the first shipments of copper from Oyu Tolgoi in June 2013. Attempts to renegotiate the OTIA and allegations of tax evasion have had little impact on Rio Tinto; while the first shipments of copper were delayed at the government’s request, Mongolia’s revenue is equally, if not more, adversely impacted by this decision, evidenced in the dramatic drop in FDI in Mongolia’s mineral sector in 2012 and 2013. It seems that the Mongolian government’s bargaining power and expectations for the profitability of Oyu Tolgoi in the short to medium term have been overly optimistic (Ognon, 2013), raising doubts over the levels of diversification and distribution that can be achieved to keep Mongolia’s development agenda safe from the resource trap.

Finally, the author raised some deeper questions about the legitimacy of the political influence of investors, particularly given the concerns of a significant portion of the Mongolian voting constituency about the viability of Oyu Tolgoi. It is too early to make any strong conclusions, but the introduction of the 2013 Investment Law and the scrapping of SEFIL suggests that investors may be having an undue influence on Mongolia’s democratic process as they push for a concept of the rule of law which favours their own interests. The domestic governance of Mongolia’s mineral sector now has the ambitious task of managing volatile mineral markets in a way that avoids the trap of investing in one resource yet continuing to attract foreign investment in that very resource. In a recent interview with Al Jazeera (2012), President Elbegdorj urges investors to view Mongolia as,

A rainbow-coloured economy... now Mongolia’s economy is mostly one colour and we would like to have more colours. Do not see Mongolia as a single mining business country... Mongolia can be a great hub between Russia and China in this region, an infrastructural hub, a financial hub, [a] high-tech hub... We have the potential.

Whether Mongolia has the potential or not currently relies a great deal on the interests of the investors and the capacity of the government to incentivise that interest in constructive directions. At the moment, investment interest in Mongolia is one-sidedly focused on the mineral sector as the Mongolian government seeks to resurrect investors’ faith in its rule of law.

[1] Fish (1998: 127) argues that Mongolia had none of the historical, cultural or economic ‘pre-requisites’ which might explain its rapid adoption of democratic reforms; Anderson et. al (2000: 527) reinforce this perspective, arguing that ‘until 1990, this country had known only nomadism and socialism, theocracy, and communism.’

[1] For example, as a result of two successive dzuds – extreme winters – in 1999 and 2000, many of the “new” herders who had migrated to the countryside in the early 1990s moved to urban centres, particularly challenging the infrastructural capacity of Ulaanbaatar, the capital city. See UNDP, 2000: 9.

[3] Oyu Tolgoi is estimated to contain 25 million ounces of gold in measured and indicated sources, and a further 37 million ounces in inferred sources. See Turquoise Hill Resources, 2013.

[4] According to the revised Minerals Law (Mongolia, 2006: Article 4.1.11), deposits are considered nationally strategic if they might affect national security, the social and economic development of the country and/or if they have the potential to produce over 5% of annual GDP.

[5] A well-known anecdote from the civic unrest over Oyu Tolgoi in the early days of negotiations was the burning of an effigy of Ivanhoe’s founder, Robert Friedland, in April 2006; Robert Friedland had a reputation for an alleged ‘trail of environmental wreckage’ left by his operations. Notably, Rio Tinto took over the management of Oyu Tolgoi in 2006 by acquiring a 51% share of Ivanhoe Mines. See New Internationalist Magazine, 2006.

[6] Four critical revisions of the 2006 Minerals law are as follows: 1.) the state maintains the right to a 34% stake in a privately-discovered mineral deposits, 2.) mining licenses are granted for an initial thirty years and can be renewed twice for twenty years each, 3.) the rights of access to adjoining land is subject to the approval of the ‘owner or possessor’ of the land, and 4.) mineral deposits are classified as strategic, common or conventional (Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement, 2009).

[7] As Rio Tinto holds the principal share of Oyu Tolgoi, it acts as a preferred stakeholder; Turquoise Hill Resources and the Mongolian Government are required to settle their debt obligations before recouping profits as common stakeholders (White, 2013).

[8] Improved levels of economic development in Mongolia mean that formerly concessional loans are being increasingly being offered at market rates (World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013: 15).

[9] This sub-title plays on a recent Reuters (Deutsch and Edwards, 2013) article entitled ‘In Tax Case, Mongolia is the Mouse that Roared.’

[10] It also cancelled double taxation treaties with Luxembourg, Kuwait, and the United Arab Emirates to avoid the same problem in the future. See McGauran, 2013.

[11] Minerals still dominated the export sector at 90.2%. See World Bank Group Mongolia, 2013: 8.

[12] The author means substantive in the legal sense of the word, as ‘defining rights and duties, as opposed to giving the procedural rules by which those rights and duties are enforced’ (Oxford English Dictionary, 2014).

Bibliography

ADB (2008) ‘Mongolia: Health and Social Protection,’ Rapid Sector Assessment October 2008 <http://www.oecd.org/countries/mongolia/42227662.pdf> Accessed 28/08/2013.

Al Jazeera (2012) ‘Is Mongolia Over-Reliant on its Resources?’ Al Jazeera Counting the Cost 1st July 2012 http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/countingthecost/2012/06/20126291118157876.html - accessed 1/11/2013.

Anderson, J. H., Lee Y. and Murrell P. (2000) ‘Competition and Privatization Amidst Weak Institutions: Evidence from Mongolia’, Economic Inquiry 38 (4).

Auty, R. (2000) ‘How Natural Resources Affect Economic Development’, Development Policy Review 18(4).

Auty, R. and Soysa, I. de (2006) Energy, Wealth and Governance in the Caucasus and Central Asia: Lessons not Learned (Abingdon: Routledge).

Barma, N.H., Kaiser, K., Le, T. M., and Vineula, L. (2011) ‘Rents to Riches? The Political Economy of Natural Resource-Led Development’ (Washington, D.C..: World Bank) <http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-0-8213-8480-0> accessed 2/03/2013.

Bedeski, R. E. (2006) ‘Mongolia as a Modern Sovereign Nation-State’, The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs 13.

Bridge, G. (2004) ‘Mapping the Bonanza: Geographies of Mining Investment in an Era of Neoliberal Reform’, The Professional Geographer 56(3).

Campi, A. (January 2012) ‘Mongolia’s Quest to Balance Human Development in its Booming Mineral-Based Economy’, Brookings Northeast Asia Commentary 51 <http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2012/01/10-mongolia-campi> accessed 29/08/2013.

Combellick-Bidney, S. (2012) ‘Mongolia’s Mining Controversies and the Politics of Place’ in Dierkes, J. (ed.) Change in Democratic Mongolia: Social Relations, Health, Mobile Pastoralism and Mining (Boston: Brill).

Deutsch, A. and Edwards, T. (2013) ‘Special Report: In Tax Case, Mongolia is the Mouse that Roared.’ Reuters 16th July 2013 < http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/07/16/us-dutch-mongolia-tax-idUSBRE96F0B620130716> accessed 1/08/2013.

Dierkes, J. (2012) ‘Introduction: Research on Contemporary Mongolia’, in Dierkes, J. (ed.) Change in Democratic Mongolia: Social Relations, Health, Mobile Pastoralism and Mining (Boston: Brill).

---. (2012a) ‘Corruption in Mongolia According to Transparency International’, Mongolia Focus Blog 5th December 2012 < http://blogs.ubc.ca/mongolia/2012/corruption-transparency-international/> accessed 1/12/2013.

Dugersuren, S. (2012) ‘Dr. Kim, Where is Mongolia’s Diversification?’ Op-ed Bretton Woods Project 8th April 2013 <http://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2013/04/art-572244/> accessed 3/07/2013.

Falconer, R. (2013) ‘Mongolian Mega-Mine Set to Transform Country’, Al Jazeera 5th June 2013 http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/06/201364111940133777.html - accessed 1/11/2013.

Fish, S. (1999) ‘The Determinants of Economic Reform in the Post-Communist World’, East European Politics and Societies 12 (2).

---. (1998) ‘Mongolia: Democracy without Prerequisites’, Journal of Democracy 9 (3).

Fisher, B.S., Batdelger, T., and Gurney, A. (2011) ‘The Development of the Oyu Tolgoi Copper Mine: An Assessment of the Macroeconomic Consequences for Mongolia,’ Report Commissioned by Rio Tinto (BAEconomics Pty Ltd and School of Economic Studies Australia: Online) <http://www.baeconomics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/OT-EIA-Book-for-Web-with-cover.pdf> Accessed 26/08/2013.

Frangos, A. and Natarajan, P. (2012) ‘Mongolia Binges on Bond Bonanza’, The Wall Street Journal 29th November 2012<http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324020804578147014152179412.html> accessed 6/01/2013.

Frankel, J. (2010) ‘The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey’, Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP10-005.

Fritz, V. (2008) ‘Mongolia: The Rise and Travails of a Deviant Democracy’, Democratization 15 (4).

---. (2002) ‘Mongolia: Dependent Democratisation’, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 18(4)

Haglund, D. (2011) ‘Blessing or Curse? The Rise of Mineral Dependence Among Low and Middle Income Countries’, Oxford Policy Management December Issue <http://www.opml.co.uk/sites/opml/files/Blessing%20or%20curse%20The%20rise%20of%20mineral%20dependence%20among%20low-%20and%20middle-income%20countries.pdf> accessed 27/08/2013.

Humphreys, M., Sachs, J.D. and Stiglitz, J. E. (2007) ‘Introduction’ in Humphreys, M., Sachs J.D. and Stiglitz J.E. (eds) Escaping the Resource Curse (New York: Columbia University Press).

IMF. (2003) ‘Mongolia: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper’, (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2003) <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2003/cr03277.pdf> accessed 1/06/2013.

---. (2013) ‘IMF Completes 2013 Article IV Mission to Mongolia’, IMF Press Release 7th October 2013 http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2013/pr13394.htm - accessed 1/11/2013.

Isakova, A., Plekhanov A. and Zettelmeyer J. (2012) ‘Managing Mongolia’s Resource Boom’, EBRD Working Paper 138. <http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/economics/workingpapers/wp0138.pdf> accessed 26/08/2013

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Henry Holt and Company).

Kohn, M. (2012) ‘Rio Tinto Polishes Image of Giant Oyu Tolgoi Mine in Mongolia’, South China Morning Post 23rd September 2012 <http://www.scmp.com/news/asia/article/1043271/rio-tinto-polishes-image-giant-oyu-tolgoi-mine-mongolia> accessed 1/08/2013.

Kohn, M. and Humber, Y. (2013) ‘Where Raptors Roamed Rio’s Dream Stirs Water Worry’, Bloomberg 10th July 2013 <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-20/where-raptors-roamed-rio-tinto-s-copper-dream-stirs-water-worry.html> accessed 29/07/2013.

Kohn, M. and Mellor, W. (2013) ‘Mongolia Scolds Rio Tinto on Costs as Mine Riches Replace Yurts’ Bloomberg 9th April 2013 <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-04-09/mongolia-scolds-rio-tinto-on-costs-as-mine-riches-replace-yurts.html> accessed 2/06/2013.

Kopstein J. S. and Reilly D. A. (2000) ‘Geographic Diffusion and the Transformation of the Postcommunist World’, World Politics 53.

Korsun, G. and Murrell, P. (1995) ‘The Politics and Economics of Mongolia’s Privatisation Programme’, Asian Survey 35 (5).

McGauran, K. (2013) ‘Should the Netherlands Sign Tax Treaties with Developing Countries?’ Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) <somo.nl/publications-en/Publication_3958/at_download/fullfile> accessed 3/08/2013.

Macalister, T. (2012) “Mongolia’s Mining Boom Could Expose It to the Resource Curse.” 20th August 2012 The Guardian < http://www.theguardian.com/business/2012/aug/20/mongolia-mining-boom-rio-tinto Accessed 2/02/2013> accessed 1/03/2013.

Macnamara, W. (2012) ‘Boom in Mongolia Deflates After Deal That Started It Is Threatened’, New York Times 10th December 2012 <http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2012/12/10/boom-in-mongolia-deflates-after-deal-that-started-it-is-threatened-2/> accessed 1/04/2013.

Mongolia (1997) 1997 Minerals Law. Official English translation of text sourced from FAOLEX Legislative Database <faolex.fao.org/docs/texts/mon37842.doc> accessed 1/03/2013.

---. (2006) 2006 Minerals Law. Official English translation of text sourced from Republic of Turkey Ministry of Economic Development <http://www.musavirlikler.gov.tr/upload/MOG/Yasalar/mineral%20law%202006.pdf> accessed 1/03/2013.

---. (2007) ‘Millennium-Development Goals-Based Comprehensive National Development Strategy’, English translation of text sourced from Ministry of Foreign Affairs <http://mofa.gov.mn/coordination/images/stories/resource_docs/nds_approved_eng.pdf> Accessed 3/03/2013.

Mongolian Mining Journal (2011) ‘All Sides Join Animated OT Debate’, Mongolian Mining Journal 14th November 2011<http://en.mongolianminingjournal.com/content/16755.shtml> accessed 1/07/2013.

Mongolian National Chamber of Commerce and Industry (2011) ‘Business Guide for Foreign Investors and Traders: Foreign Trade’, <http://en.mongolchamber.mn/investment_guide/2.htm> Accessed 27/08/2013.

Moody’s Investor Services (2013) ‘Moody Assigns Negative Outlook to Mongolian Banking System’, <https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-assigns-negative-outlook-to-Mongolian-banking-system--PR_270591> accessed 15/07/2013.

Moran, T. H. (2013) ‘Avoiding the “Resource Curse” in Mongolia’, Peterson Institute for International Economics Policy Brief No. 13-18 <http://www.iie.com/publications/pb/pb13-18.pdf> accessed 27/08/2013.

New Internationalist Magazine (2006) ‘Robert Friedland’, New Internationalist Magazine 392 <http://newint.org/columns/worldbeaters/2006/08/01/> accessed 1/07/2013.

Ognon, K. (2013) ‘Sovereign Wealth Fund: Case of Mongolia’, Powerpoint presentation prepared for the African Development Bank. <https://www.google.co.uk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&ved=0CDEQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.afdb.org%2Ffileadmin%2Fuploads%2Fafdb%2FDocuments%2FGeneric-Documents%2FPresentation%2520-%2520Sovereign%2520Wealth%2520Fund%2520-%2520Case%2520of%2520Mongolia.pps&ei=PrMfUvquPOLm7Ab7tYDQDw&usg=AFQjCNEMDO_rrMP5Th2cGpH02CtiR6rtbA&sig2=xMIOz7kQlu3-3_jrvm2E0A&bvm=bv.51495398,d.ZGU> accessed 27/08/2013.

Packard, C. and Khurelbold, O. (2010) ‘The Changing Legal Environment for Mining in Mongolia’, Anderson and Anderson LLP <http://www.anallp.com/the-changing-legal-environment-for-mining-in-mongolia-2/> accessed 1/03/2013.

Pistilli, M. (2012) ‘Resource Investors to Watch Mongolian Parliamentary Elections’, Resource Investing News 12th March 2012 <http://resourceinvestingnews.com/32963-resource-investors-watch-mongolian-parliamentary-elections-resource-nationalism-rio-tinto-ivanhoe-mines-oyu-tolgoi.html> accessed 2/09/2013.

Reeves, J. (2011) ‘Resources, Sovereignty and Governance: Can Mongolia Avoid the “Resource Curse?”’ Asian Journal of Political Science 19 (2).

Rio Tinto (2013) ‘Oyu Tolgoi’, <http://www.riotinto.com/ourbusiness/oyu-tolgoi-4025.aspx> accessed 1/03/2013.

Rio Tinto Mongolia (2013) ‘Oyu Tolgoi: Project Details’, <http://www.riotintomongolia.com/ENG/oyutolgoi/884.asp> accessed 1/03/2013.

Riseborough, J. and Kohn, M. (2013) ‘Mongolia says Rio Mine Audit Seeks Answers on $2 Billion Overrun’, Bloomberg 17th April 2013 <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-04-17/mongolia-says-rio-mine-audit-seeks-answers-on-2-billion-overrun.html> accessed 4/08/2013.

Rossabi, M. (2005) Modern Mongolia (Los Angeles: University of California Press)

Rosser, A. (2006) ‘The Political Economy of the Resource Curse: A Literature Survey’, Institute of Development Studies Working Paper 268 <http://www2.ids.ac.uk/gdr/cfs/pdfs/wp268.pdf> accessed 26/08/2013.

Sachs, J. (1994) ‘Understanding Shock Therapy’, The Social Market Foundation Occasional Paper 7 (London).

Sneath, D. (2003a) ‘Land-use, the Environment and Development in Post-Socialist Mongolia’, Oxford Development Studies 31 (4).

--- (2003b) ‘Lost in the Post: Technologies of Imagination, and the Soviet Legacy in Post-Socialist Mongolia’, Inner Asia 5.

--- (2006) ‘The Rural and the Urban in Pastoral Mongolia’, in Bruun, O. and Narangoa, L. (eds.) Mongols from Country to City: Floating Boundaires, Pastoralism and City Life in the Mongol Lands (Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies).

Stiglitz, J. (2007) ‘What is the Role of the State?’ in Humphreys, M., Sachs, J. D. and Stiglitz, J. E. (eds.) Escaping the Resource Curse (New York: Columbia University Press).

Sukhbaatar, S. (2012) ‘Law and Development, FDI, and the Rule of Law in Post-Soviet Central Asia’, in McAlinn, G. P. and Pejovic, C. (eds.) Law and Development in Asia (Oxon, UK: Routledge).

Tumenbayer, N. (2002) ‘Herders’ Property Rights vs. Mining in Mongolia’, Conference on Environmental Conflict Resolution, Watson Institute for International Studies, Brown University, Providence, RI, Spring 2002 <http://www.uvm.edu/~shali/Mining%20Mongolia%20paper.pdf> accessed 1/06/2013.

Turquoise Hill Resources (2013) ‘Oyu Tolgoi Mongolia’, <http://www.turquoisehill.com/s/Oyu_Tolgoi.asp.> accessed 1/04/2013.

---. ‘Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement’, (2009) Text published online by Turquoise Hill Resources <http://www.turquoisehill.com/i/pdf/Oyu_Tolgoi_IA_ENG.PDF> accessed 2/02/2013.

Usoskin, S. (2011) ‘Paushok et al. v. Mongolia: Windfall Profit Tax and Immigration Requirements Compatible with FET Standard’, CIS Arbitration Forum <http://cisarbitration.com/2011/05/14/paushok-et-al-v-mongolia-windfall-profit-tax-and-immigration-requirements-compatible-with-fet-standard/> accessed 3/03/2013.

Walker, A. (2013) ‘Mongolia and Kazakhstan: Populist Policies’, The International Resource Journal Online <http://www.internationalresourcejournal.com/features/july12_features/mongolia_and_kazakhstan_populist_policies.html> accessed 5/10/2013.

White, B. (2013) ‘In-Depth Analysis: OT Dispute and Expenditure Overruns’, The Mongolist 10th March 2013 <http://www.themongolist.com/blog/government/58-in-depth-analysis-ot-dispute-and-expenditure-overruns.html> accessed 1/08/2013.

World Bank (1996) ‘Mongolia: Poverty Assessment in a Transition Economy’ (Ulaanbaatar: World Bank).

--- (2004) ‘Mongolia Mining Sector: Managing the Future’, <http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2006/01/6761762/mongolia-mining-sector-managing-future> accessed 3/03/2013.

World Bank Data, ‘GDP Per Capita 1981-1989 – Mongolia’, <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.> accessed 13/06/2013.

---‘GDP Per Capita Growth (% annual) – Mongolia’, <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.KD.ZG?page=4.> accessed 12/06/2013.

---‘Public Spending on Education Total (% government expenditure)’, <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.XPD.TOTL.GB.ZS > accessed 1/08/2013.

--- ‘Gini Index’, <http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI> accessed 1/08/2013.

World Bank Group – Mongolia (April 2013) ‘Mongolia Economic Update’, <http://www.worldbank.org/content/dam/Worldbank/document/EAP/Mongolia/MQU_April_2013_en.pdf> accessed 30/08/2013.

World Growth (2008) ‘Averting the Resource Curse’, <http://202.179.0.198/world/downloads/WG_Mongolia_english.pdf> accessed 1/06/2013.

--- (2009) ‘The Oyu Tolgoi Investment Agreement: Why it Works for Mongolia,’ <http://worldgrowth.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/OT-Investment-Agreement_ENG-A4.pdf> accessed 1/06/2013.

Zand, B. (2013) ‘Mining the Gobi: The Battle for Mongolia’s Resources’, Spiegel International Online 7th August 2013 <http://www.spiegel.de/international/world/mining-the-gobi-desert-rio-tinto-and-mongolia-fight-over-profits-a-915021.html> accessed 1/09/2013.

Bibliography

ADB (2008) ‘Mongolia: Health and Social Protection,’ Rapid Sector Assessment October 2008 <http://www.oecd.org/countries/mongolia/42227662.pdf> Accessed 28/08/2013.

Al Jazeera (2012) ‘Is Mongolia Over-Reliant on its Resources?’ Al Jazeera Counting the Cost 1st July 2012 http://www.aljazeera.com/programmes/countingthecost/2012/06/20126291118157876.html - accessed 1/11/2013.

Anderson, J. H., Lee Y. and Murrell P. (2000) ‘Competition and Privatization Amidst Weak Institutions: Evidence from Mongolia’, Economic Inquiry 38 (4).

Auty, R. (2000) ‘How Natural Resources Affect Economic Development’, Development Policy Review 18(4).

Auty, R. and Soysa, I. de (2006) Energy, Wealth and Governance in the Caucasus and Central Asia: Lessons not Learned (Abingdon: Routledge).

Barma, N.H., Kaiser, K., Le, T. M., and Vineula, L. (2011) ‘Rents to Riches? The Political Economy of Natural Resource-Led Development’ (Washington, D.C..: World Bank) <http://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/book/10.1596/978-0-8213-8480-0> accessed 2/03/2013.

Bedeski, R. E. (2006) ‘Mongolia as a Modern Sovereign Nation-State’, The Mongolian Journal of International Affairs 13.

Bridge, G. (2004) ‘Mapping the Bonanza: Geographies of Mining Investment in an Era of Neoliberal Reform’, The Professional Geographer 56(3).

Campi, A. (January 2012) ‘Mongolia’s Quest to Balance Human Development in its Booming Mineral-Based Economy’, Brookings Northeast Asia Commentary 51 <http://www.brookings.edu/research/opinions/2012/01/10-mongolia-campi> accessed 29/08/2013.

Combellick-Bidney, S. (2012) ‘Mongolia’s Mining Controversies and the Politics of Place’ in Dierkes, J. (ed.) Change in Democratic Mongolia: Social Relations, Health, Mobile Pastoralism and Mining (Boston: Brill).

Deutsch, A. and Edwards, T. (2013) ‘Special Report: In Tax Case, Mongolia is the Mouse that Roared.’ Reuters 16th July 2013 < http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/07/16/us-dutch-mongolia-tax-idUSBRE96F0B620130716> accessed 1/08/2013.

Dierkes, J. (2012) ‘Introduction: Research on Contemporary Mongolia’, in Dierkes, J. (ed.) Change in Democratic Mongolia: Social Relations, Health, Mobile Pastoralism and Mining (Boston: Brill).

---. (2012a) ‘Corruption in Mongolia According to Transparency International’, Mongolia Focus Blog 5th December 2012 < http://blogs.ubc.ca/mongolia/2012/corruption-transparency-international/> accessed 1/12/2013.

Dugersuren, S. (2012) ‘Dr. Kim, Where is Mongolia’s Diversification?’ Op-ed Bretton Woods Project 8th April 2013 <http://www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2013/04/art-572244/> accessed 3/07/2013.

Falconer, R. (2013) ‘Mongolian Mega-Mine Set to Transform Country’, Al Jazeera 5th June 2013 http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/2013/06/201364111940133777.html - accessed 1/11/2013.

Fish, S. (1999) ‘The Determinants of Economic Reform in the Post-Communist World’, East European Politics and Societies 12 (2).

---. (1998) ‘Mongolia: Democracy without Prerequisites’, Journal of Democracy 9 (3).

Fisher, B.S., Batdelger, T., and Gurney, A. (2011) ‘The Development of the Oyu Tolgoi Copper Mine: An Assessment of the Macroeconomic Consequences for Mongolia,’ Report Commissioned by Rio Tinto (BAEconomics Pty Ltd and School of Economic Studies Australia: Online) <http://www.baeconomics.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/OT-EIA-Book-for-Web-with-cover.pdf> Accessed 26/08/2013.

Frangos, A. and Natarajan, P. (2012) ‘Mongolia Binges on Bond Bonanza’, The Wall Street Journal 29th November 2012<http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324020804578147014152179412.html> accessed 6/01/2013.

Frankel, J. (2010) ‘The Natural Resource Curse: A Survey’, Harvard Kennedy School Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP10-005.

Fritz, V. (2008) ‘Mongolia: The Rise and Travails of a Deviant Democracy’, Democratization 15 (4).

---. (2002) ‘Mongolia: Dependent Democratisation’, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 18(4)

Haglund, D. (2011) ‘Blessing or Curse? The Rise of Mineral Dependence Among Low and Middle Income Countries’, Oxford Policy Management December Issue <http://www.opml.co.uk/sites/opml/files/Blessing%20or%20curse%20The%20rise%20of%20mineral%20dependence%20among%20low-%20and%20middle-income%20countries.pdf> accessed 27/08/2013.

Humphreys, M., Sachs, J.D. and Stiglitz, J. E. (2007) ‘Introduction’ in Humphreys, M., Sachs J.D. and Stiglitz J.E. (eds) Escaping the Resource Curse (New York: Columbia University Press).

IMF. (2003) ‘Mongolia: Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper’, (Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund, 2003) <http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2003/cr03277.pdf> accessed 1/06/2013.

---. (2013) ‘IMF Completes 2013 Article IV Mission to Mongolia’, IMF Press Release 7th October 2013 http://www.imf.org/external/np/sec/pr/2013/pr13394.htm - accessed 1/11/2013.

Isakova, A., Plekhanov A. and Zettelmeyer J. (2012) ‘Managing Mongolia’s Resource Boom’, EBRD Working Paper 138. <http://www.ebrd.com/downloads/research/economics/workingpapers/wp0138.pdf> accessed 26/08/2013

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Henry Holt and Company).

Kohn, M. (2012) ‘Rio Tinto Polishes Image of Giant Oyu Tolgoi Mine in Mongolia’, South China Morning Post 23rd September 2012 <http://www.scmp.com/news/asia/article/1043271/rio-tinto-polishes-image-giant-oyu-tolgoi-mine-mongolia> accessed 1/08/2013.

Kohn, M. and Humber, Y. (2013) ‘Where Raptors Roamed Rio’s Dream Stirs Water Worry’, Bloomberg 10th July 2013 <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-20/where-raptors-roamed-rio-tinto-s-copper-dream-stirs-water-worry.html> accessed 29/07/2013.

Kohn, M. and Mellor, W. (2013) ‘Mongolia Scolds Rio Tinto on Costs as Mine Riches Replace Yurts’ Bloomberg 9th April 2013 <http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-04-09/mongolia-scolds-rio-tinto-on-costs-as-mine-riches-replace-yurts.html> accessed 2/06/2013.

Kopstein J. S. and Reilly D. A. (2000) ‘Geographic Diffusion and the Transformation of the Postcommunist World’, World Politics 53.

Korsun, G. and Murrell, P. (1995) ‘The Politics and Economics of Mongolia’s Privatisation Programme’, Asian Survey 35 (5).

McGauran, K. (2013) ‘Should the Netherlands Sign Tax Treaties with Developing Countries?’ Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) <somo.nl/publications-en/Publication_3958/at_download/fullfile> accessed 3/08/2013.