Paradox of neoliberal democracy

Paradox of neoliberal democracy

Paradoxical Technocratic Economic Governance

The paradox of neo-liberal democracy describes a perennial tension between national politics and global markets in advanced democracies amid complex interdependence: the rules, laws and institutions that sustain integrated global markets curtail national sovereignty. Put simply, as significant parts of economic governance transcend (exclusive) national control, governing in the political economic interests of one’s citizenry becomes more complicated.

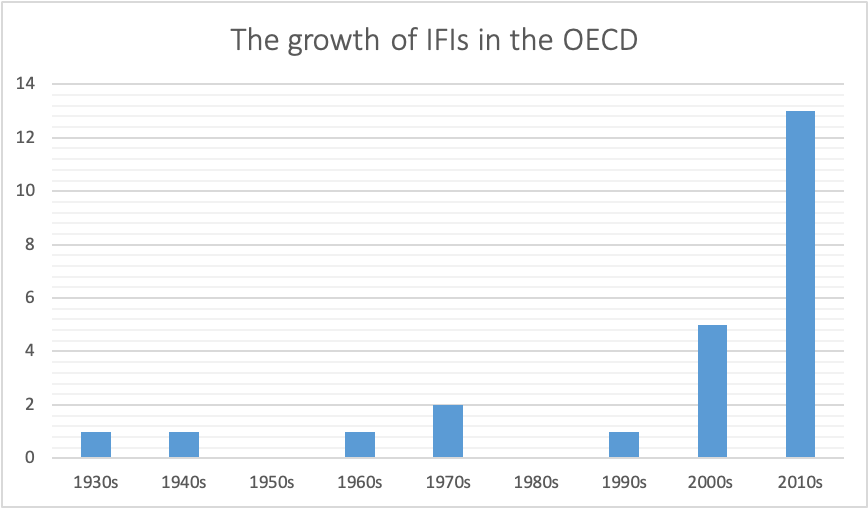

On the one hand, a government claims sovereignty of a national state, and builds a regulatory edifice within a national political territory, to manage ‘its’ national economy. On the other hand, European and global markets are maintained by densely overlapping transnational jurisprudence and regulations. Global capitalism is sustained by international economic institutions, overlain with wide-ranging supra-national multilateral agreements, and maintained by forms of pooled sovereignty (see e.g. Clift and Woll 2012a; 2012b).

These are inextricably part of 21st Century international economic relations. National politicians have to grapple with ‘the gap between political debates and decisions, which remain obstinately national, and economic rule-making, which is fundamentally transnational’ (Crouch 2019, 46). This tension goes to the heart of acrimonious debates about European market integration in British politics. It animated the saga of Brexit.

One means to address or mitigate the paradox of neo-liberal democracy is to pool sovereignty and participate in supra-national market-making, for example through European integration. Another (highly problematic and deeply flawed) route out of the dilemma presented by the paradox of neo-liberal democracy is dissimulation, rather than facing up to stark economic policy trade-offs and the complexities and difficulties of economic management.