Jamie Arathoon on Training a Pet to be an Assistance Dog

My PhD research is undertaken with the charity Dog A.I.D. who are part of the ADUK (Assistance Dogs UK) and help physically disabled people train their own pets to become assistance dogs. This offers an interesting point of exploration, as most UK-based assistance dog charities provide people with an already trained assistance dog. Unique to Dog A.I.D. then, the clients already have a bond with their dog, and this can impact training in multiple ways. Some dogs were already trained to a good standard whereas some had bad habits not acceptable for an assistance dog. These good standards might be the ability to sit, wait, and come when called, all important assistance dog skills, whereas bad habits might be barking at noise, or scent-marking, both common amongst pet dogs. The training, through positive methods, builds on the human-pet bond that already exists. For example, if the dog and human have already learnt a good sit, wait, and recall, these skills can be transferred to learn both a settle, where the dog lies quietly often while other activities are taking place, and an emergency stop, which are both vital parts of life skills training.

A Dog A.I.D. partnership begins through an initial application to the charity and an assessment of the dog’s health and body by a Dog A.I.D. volunteer. There is also an interview to understand how the human may benefit from the dog’s help. The partnership is then paired with a Dog A.I.D. trainer local to them. The training is completed either at the client’s home or as part of a group, depending on how many clients the volunteer trainer has. Reliance is placed on the clients doing training out-with the training session, within the home, garden, or local shopping malls. Spatial experiences thus form an essential element in shaping the partnership. The training is undertaken over three levels, including socialisation and familiarisation, life skills tasks such as sit, down, stay, recall, and emergency stop, and tasks such as picking up, pushing, or pulling objects.

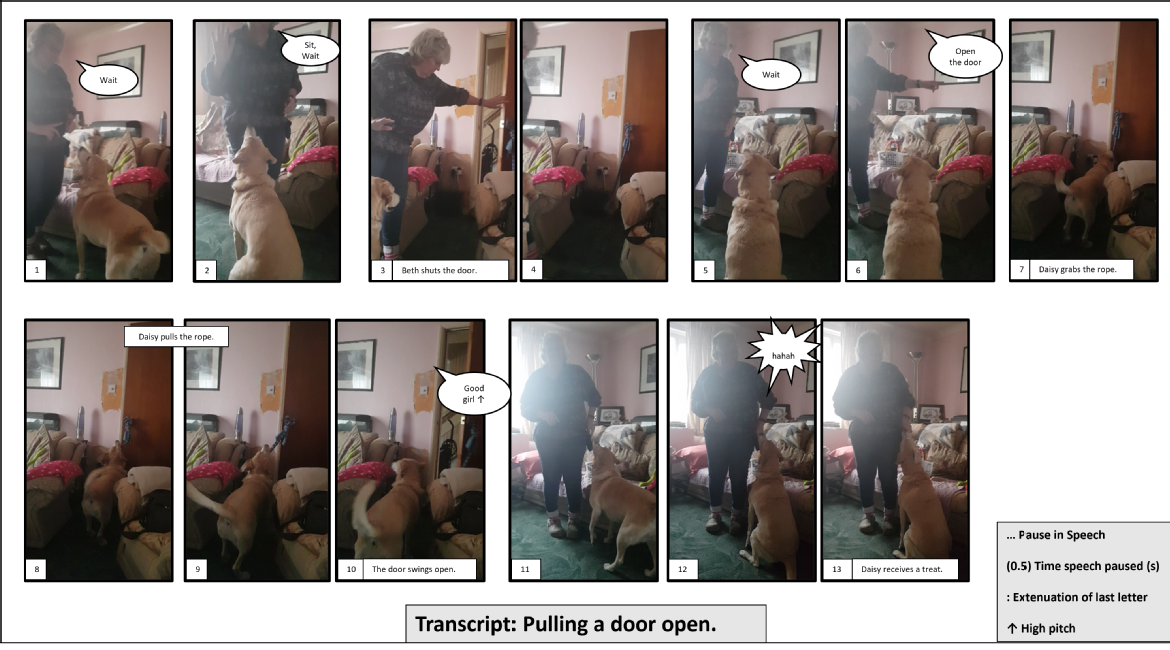

What is most important is that it is the human and dog that do the training together, as a multi-species partnership. This helps them directly build on their existing human-pet bond through ongoing embodied engagement. For example, in the graphic transcript below, Beth and Daisy are learning to pull the door open. This involves attunement (Despret, 2004) through verbal language, tone, eye contact, gestures, and embodied action, but also requires the ability to engage with the rope and door. This material engagement requires prior knowledge built through playing the game tug as a human-pet dyad. It requires human and dog to be accustomed to one another’s presence, their touch, tone of voice, smell, and language. The task is completed through these embodied interactions and the application of their shared knowledge developed as a human-pet dyad. Furthermore, using positive methods, and specifically verbal praise and rewards, helps the bond develop further as Daisy is rewarded for opening the door, which reinforces her desire to work.

The experience of training, for both Beth and Daisy specifically, is one of enjoyment. The 12th panel in the video transcript (illustrated here) shows this as Daisy moves towards Beth’s hand for the reward, nudging it in anticipation, and Beth laughing in response.

The enjoyment of training is built over time as the partnership develops through their continued co-learning (Haraway, 2003; 2008). Additionally, the speed at which Beth and Daisy completed tasks together during the ethnographic work showed the development of their strong bond. The ‘pull open the door’ task in the transcript took place over just 18 seconds. Moreover, throughout the interview Daisy kept bringing Beth items without being asked, showing a willingness and desire to work together. Indeed, Beth summed up this relationship stating:

“Daisy is quite shy, she prefers me, and this is the bond … she is my pet and my assistance dog but also my carer”.

Training through Dog A.I.D. thus helps build on the bond the human and dog already share. The training enhances this bond through their ongoing embodied interaction within particular spaces. It is important to note though that the ‘pet’ aspect of the dog’s ascribed identity doesn’t disappear, rather, they occupy multiple positionalities in relation to their human and the spaces in which they co-exist. These identities may contain anthropomorphic understandings of the bond between human and assistance dog, but is a vital part of the human’s understanding of the relationship. In this case, anthropomorphism works to open up potentialities of human-assistance dog co-existence, enhancing the bond between human and animal, and creating new, ethico-political potentialities (de la Bellacasa, 2017) for their shared lifeworlds.

References:

de la Bellacasa, M.P. (2017) Matters of care. University of Minnesota Press.

Despret, V. (2004) The body we care for: Figures of anthropo-zoo-genesis. Body & Society, 10(2-3), 111-134.

Haraway, D. (2003) The companion species manifesto. Prickly Paradigm Press.

Haraway, D. (2008) When species meet. University of Minnesota Press.

Biography

Jamie Arathoon is a Human Geography PhD candidate at the School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, University of Glasgow. Their PhD research explores the contexts of assistance dog training and the ways care crosses species boundaries between physically disabled people and their assistance dogs. They have wider interests in animal geographies, disability geographies, health and wellbeing, more-than-human geographies, and qualitative methods. They are also working on a project on the geographies of pet theft with Dr Daniel Allen, Adam Peacock (Keele University), and Dr Helen Selby-Fell (Open University).