Bryan Brazeau

Report on Newberry Early Career Resarch Fellowship 2019-2020:

Thanks to a 2019-2020 Warwick Newberry Early Career Research Fellowship, I spent nearly two weeks at the Newberry Library in September 2019 working on a project that investigated the genre of lagrime/weeping poetry in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth- century Europe with Dr. Anne Boemler (Northwestern University). Our research project aimed to rethink models of reception by examining a genre of Christian devotional poetry across confessional and linguistic divides.

This project focussed on a unique genre of lyrical narrative that was quite popular in late sixteenth-century Italy, Spain, France, and England. In particular, weeping as devotional practice was an important part of counter-reformation Catholic spirituality. Joseph Imorde has demonstrated how the Catholic Reformation placed a great deal of new emphasis on weeping, “elevating those inner emotions, which at the best of times flowed down from the fountain of God’s mercy, to the status of a reliable and verifiable means of knowledge;” crying in public became a widespread fashion, and Pope Clement VIII wept so often and so copiously that people sometimes questioned the authenticity of his tears.[1]

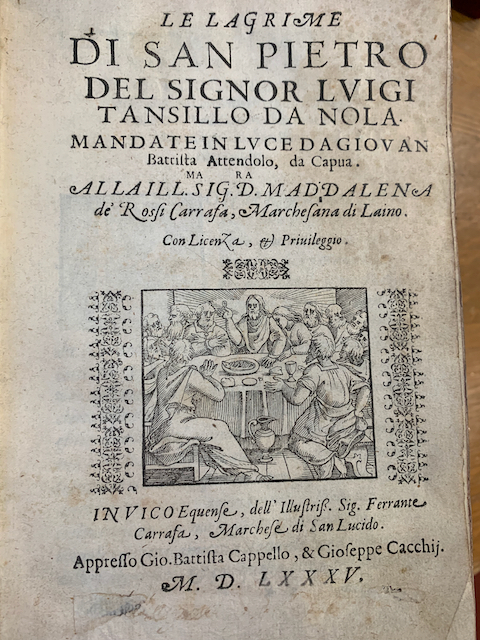

Lagrime poems were nearly all written in ottava rima, featured a mix of narrative and lyric content, and occasionally presented themselves as a new type of epic. They focused on the penitence of various figures from the Gospels, whose weeping was often presented as exemplary. As Virginia Cox has discussed, the poem which launched this genre was Luigi Tansillo’s Lagrime di San Pietro, a text that describes the penitence and weeping of Saint Peter over the three days following his denial of Christ. Tansillo’s poem inspired others to follow in his stead, serving as the model for Erasmo di Valvasone’s Le lacrime di Santa Maria Maddalena (1586), Torquato Tasso’s Le lagrime della beata Vergine and Le lagrime di Cristo (1593), along with Angelo Grillo’s Lagrime del penitente (1594), among others. The poem also inspired a number of musical compositions, such as Orlando di Lasso’s setting of the poem to music in a cycle of 20 madrigals.

Lagrime poems have not received adequate scholarly attention, neither in their Italian context nor in their wider pan-European manifestations. While scholars such as Jesús Gracilano González Miguel have demonstrated the influence of lagrime poetry in early modern France and Spain,[2] fewer scholars have noted the links between these poems and the production of English Catholic writers, such as Robert Southwell’s St. Peters Complaint (1595). This latter poem was often paired with Saint Mary Magdalens Funerall Teares by the same author and appeared in at least fifteen editions between 1595 and 1640. The poem strongly demonstrates influences of Tansillo, Valvassone, and other Italian authors of lagrime poetry. Along with Southwell, one might also include the weeping poems of Aemelia Lanyer and Gervase Markham as further examples of lagrime poetry in early seventeenth-century England.[3]

Rather than examining these poems simply within their national contexts, Dr. Boemler and I conducted a survey using a wide variety of materials at the Newberry Library, discovering nearly 100 poems within the genre published in Italy, Spain, France, and England between 1550 and 1650. Conceiving of the genre as pan-European, translinguistic, and transconfessional allowed us to explore the near-simultaneous effloresence of this genre which challenges our traditional categorisation of literature within national, linguistic, and confessional contexts. The popularity of this genre in the period, we believe, demonstrates an affective identification between readers and text, while speaking more broadly to how we might reconceptualise early modern literature using principles from the history of the emotions.

We have submitted a draft of our article, entitled “Tears in Heaven: Tracing the Contours of a Pan-European Confessional Genre’ and are awaiting the results of the peer review process.

[1] Joseph Imorde, “Tasting God: The Sweetness of Crying in the Counter-Reformation,” in Religion and the Senses in Early Modern Europe, 257-269, eds. Wietse De Boer and Christine Göttler (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2013), 267.

[2] Jesús Graciliano González Miguel, Presencia napolitana en el siglo de oro espanõl (Luigi Tansillo) (Salmanca: Ed. Universidad de Salamanca, 1979).

[3] Aemelia Lanyer, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611); Gervase Markham, The teares of the beloved; or, the Lamentation of Saint John (1600); and Idem. Mary Magdalens Lamentations for the Losse of her Maister Jesus (1601).

Luigi Tansillo, Frontispiece from Le Lagrime di San Pietro del Signor Luigi Tansillo da Nola, Mandate in Luce da Giovanni Battista Attendolo da Capua. (Vico Equense: Gioseppe Cacchi, 1585).

Newberry Library Case Y 712 T.1392