Research Award Report by Aidan Norrie

Thanks to the Dr Greg Wells Research Award, I was able to spend two days in the Cambridge University Library conducting research for my forthcoming monograph, Elizabeth I and the Old Testament: Biblical Analogies and Providential Rule (Arc Humanities Press).

Scholars have long analysed the use of biblical analogies as part of Tudor and Stuart royal iconography. Using the example of a biblical figure, monarchs demonstrated the divine precedent for their decisions, and subjects counselled their monarch to emulate the actions of a divinely favoured biblical figure. Elizabeth I of England was the subject of the greatest number of biblical analogies in the early modern period, but the scholarship still lacks a book-length work that analyses these analogies as a distinct phenomenon. It is this gap that my book will address.

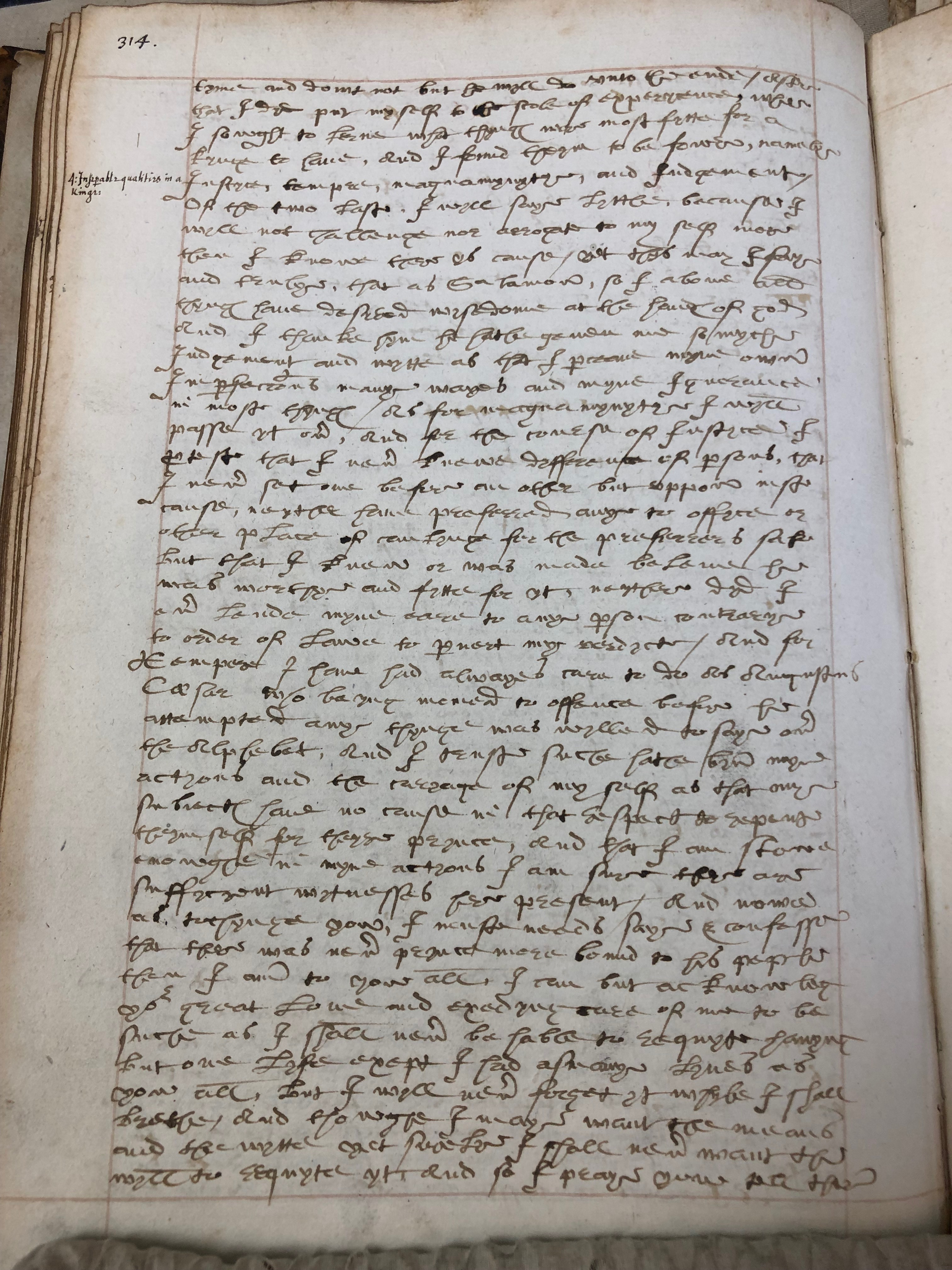

My main focus for the trip was to view Cambridge University Library MS Gg III, as it contains two manuscripts that are key to my book’s argument.

Chapter 1 of my book, in a departure from the existing scholarship, is devoted to Elizabeth’s own invoking of biblical analogies. At multiple points in her reign, Elizabeth invoked the example of an Old Testament figure to explain her action (or indeed, lack of action). Crucially, Elizabeth compared herself to both King David and King Solomon during the parliamentary debates surrounding the trial of Mary, Queen of Scots, and the subsequent calls that the Scottish queen be executed. MS Gg III contains a copy of a speech Elizabeth delivered in her second response to the parliamentary petition urging that she order Mary’s execution, which was delivered on 24 November 1586. In it, Elizabeth compared herself to Solomon: ‘I [have] sought to lerne what thynges wer most fitte for a kynge to have, and I found theym to bee foure, namely justice, temper[ance], magnamymyte, and judgement. Of the two last, I will saye little, because I will not challenge nor arrogate to my self more than I knowe there is cause. Yet thys maye I saye and trulye, that as Salomon, so I above all thynges have desyred wysdome at the handes of God.’ Seeing the manuscript in person was particularly important, as I discovered that the modern transcription had transcribed ‘my self’ as ‘myself’—while not a major alteration, ‘my self’ is more true to Elizabeth’s own conception of the role of a monarch.

Significantly, and as I have noted, Elizabeth’s speech was delivered in response to a parliamentary petition. A copy of this petition survives in MS Gg III. After viewing the petition, I am convinced that the content of Elizabeth’s speech was intended to not only assert her monarchical authority, but to also respond to various points raised within the petition. We cannot know whether the content of draft speeches were actually spoken, but given the petition Elizabeth was responding to invoked both the example of David and Solomon, it seems more than likely that the analogy with Solomon was included in the delivered version.

An unexpected bonus of the trip was seeing a copy of my book, Women on the Edge in Early Modern Europe in the ‘wild’ in the open stacks of the Cambridge UL. After staring at early modern scrawl for an extended period, it was a nice injection of fresh energy.

This trip would have been almost impossible without the Dr Greg Wells Research Award. Cambridge is not the most accessible of places from where I live, and being able to devote a generous amount of time to research because I was staying for more than one day really was an unparalleled luxury. I am very grateful to have been one of the 2019 beneficiaries of this award.

Women on the Edge in Early Modern Europe with its happy editor.

Syndics of Cambridge University Library, MS Gg.III.34, 314