The #spycops scandal: Subversion and Collateral Intrusions

By Chris Brian

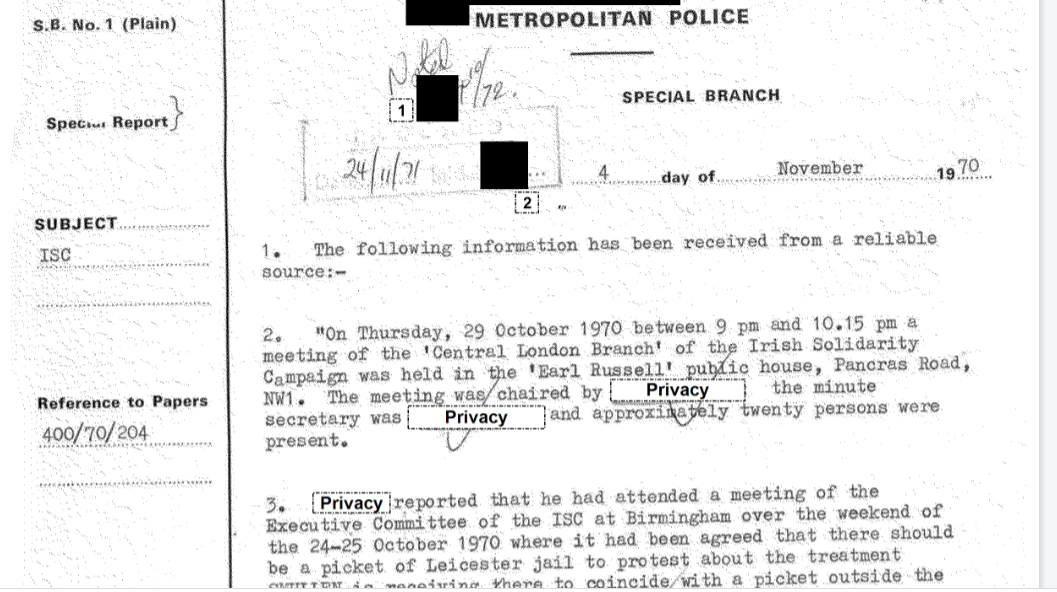

Between 1968 and 2010, 144 undercover officers were deployed into groups, filing 1000s of reports on their activities and intertwining themselves, often damagingly, into the lives of political activists.

The Undercover Policing Inquiry has revealed that of the thousands of now-published Special Branch reports, only a few contained information relevant to the undercover unit Special Demonstration Squad’s (SDS) stated primary objective: controlling public order.

Instead, most of the reports recorded the legitimate and unremarkable meetings of activist groups – very few of which discussed disorder or criminal activity of any kind.[1] In other words, they interfered with the right to privacy and freedom of expression on a massive scale.

Moreover, the reports contained personal details of those attending the meetings with no obvious relevance to public order, including their sexuality, living arrangements and medical conditions.

Why did this happen – and how did it go on for 43 years?

The answer partially lies within the Metropolitan Police's Special Branch's longstanding duty in the 20th Century to provide MI5 with information on subversion and subversives. This meant that any undercover officer's deployment could be justified via this broad definition:

…activities which threaten the safety or well-being of the State and are intended to undermine or overthrow parliamentary democracy by political, industrial, or violent means.[2]

Therefore, the long-term aspirations to revolution and the overthrow of the British State contained within most groups' rhetoric and philosophy (no matter how unrealistic in practice) meant that surveillance of almost all groups on the left could be justified in this way.

In addition, there was no legislative regime governing this type of surveillance. It might seem surprising that until 1985, with the Interception of Communications Act (which only concerned electronic surveillance), there was no primary legislation governing surveillance.

It was not until 15 years after this that the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) (2000) first regulated the type of surveillance practiced by the Special Demonstration Squad and its successor, the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (NPOIU).

Before this, the only contemporaneous guideline was a short Home Office directive forbidding spies and informers from acting as agent provocateurs.[3] Therefore, in effect, the Special Branch's remit was the only guardrail it had. One might have hoped that this lack of regulation and loose remit might have been offset by management imposing some form of quality control on the information collected. However, this was also entirely absent.

The results of this lack of proper parameters, both internal and external, are illustrated in several ways in the undercover officers’ reporting and targeting.

One of the first undercover officers to give evidence was one who used the cover name ‘Doug Edwards’. He happily admitted that his leading target group – the Independent Labour Party - was neither a subversive nor a public order threat. Instead, he claimed that he used it as a ‘hammer to swing’ into supposedly more dangerous groups. However, nothing in Edwards' reporting was more serious than 'sit-ins' and other non-violent direct action.[4]

This 'stepping-stone' approach became a hallmark of the SDS's operation until 2008. Undercover officers were often free to choose the groups they infiltrated. For instance, undercover officer 'Graham Coates' switched from the Socialist Workers Party to anarchist groups simply because he was more interested in them. One officer, ‘Barry Tompkins’, even formed his own three-person grouplet.

‘Tompkins’ also recorded many intimate personal details in his reporting. One of his reports touches on an individual’s immigration status – where it is alleged he is in a ‘marriage of convenience’. It also mentions that they are in a ‘sexual relationship with another [party] member’ and that ‘judging by the depressing regularity with which [privacy] suffers from attacks of cystitis, neither is permitting [privacy]'s tenuous position in the United Kingdom to interfere with more immediate needs.'In another report, a member of the Revolutionary Communist Party (that he infiltrated) had an abortion. This is the only information contained in this report – other than speculation about whom the father may have been. However, 'Tompkins' was not the only one to report such details. Other undercover officers' reporting included activists being admitted to hospitals for heart attacks, births, abortions, and a ‘nervous breakdown’.

This is all before we start to consider the sexist and racialised descriptions in the reports, including that one woman attended meetings with her ten-year-old daughter, noting her as ‘half-cast’ (sic) and that there was ‘no male wage-earner supporting them.’ The collection of this kind of information would later be defined by the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) as illegitimate ‘Collateral Intrusion’.

In 2023, the Chair of the Undercover Policing Inquiry, Sir John Mitting, stated that of the fifty-three deployments between 1968 and 1982, only three could be justified in policing terms.

The Cold War ended in 1989 with the fall of the Berlin Wall. Subversion also slowly faded from use. A decade later, RIPA was introduced.

This legislation required that any surveillance was compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). This included considering whether the surveillance was 'necessary' and ‘proportionate' and required the authorising police officer to assess the risk of ‘collateral intrusion’ – the recording of information from the surveillance of individuals irrelevant to the task at hand. Therefore, it might be assumed that the successor unit to the SDS – the NPIOU (which started in 1999) would have operated entirely differently.

In short, it did not. Rather like its predecessor unit, the SDS, ‘collateral intrusion’ better describes its modus operandi, rather than something it sought to avoid.

Kate Wilson won a Human Rights case in the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (IPT) regarding her surveillance by NPIOU, including a sexual relationship with undercover officer Mark Kennedy in 2021.[5]

Kennedy was deployed into the anarchist-environmental milieu, based in Nottingham, but spied on similar groups and mobilisations across Europe. He also had several other sexual relationships and his undisclosed involvement in two protests has resulted in 49 convictions being overturned – and a further trial collapsing.

The judgment said that the NPOIU’s operation focusing on her and other activists ‘showed no appreciation of the intrusion into the private lives of many people unlikely to be involved in any criminal or improper activity’. Most importantly, it also found the police by allowing Kennedy’s relationship to continue for two years had breached Kate’s human rights, including a breach of Article 3 ECHR, which prohibits torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, and punishment.

One of Mark Kennedy’s authorised targets was neither an activist nor an activist group. Instead, it was a community centre in Nottingham, SUMAC. While it is true the SUMAC centre hosted a significant number of activist meetings, the IPT judgment made clear that the breadth of Mark Kennedy’s infiltration (‘a fishing expedition’) would only have been justified if the building was ‘harbouring terrorist groups, which could not be infiltrated in any other way’. To be clear, there was never a suggestion that terrorist groups were resident at the centre.

While the judgment addresses the poor management and lack of any genuine critical assessment of Kennedy's deployment, was ineffectual supervision the only reason things went so dramatically and disastrously wrong?

Currently, most of Kennedy’s reporting is not in the public domain. However, the reporting on Wilson contains as much, if not more, superfluous personal information as in the earlier SDS era – even in the absence of the Cold War 'subversive threat'.

Unsurprisingly, some officers served in the SDS before transferring to the NPOIU, so the transmission of police culture may have overridden the new legislation introduced in 2000. Perhaps, even decades later, the ingrained habits of the Cold War have proved hard to dispense with.

[1] The Inquiry examined a sample of reports. Out of the 2600 reports, only 200 contained information on plans for forthcoming events that might have impacted public order in London and elsewhere.

[2] This was the definition given in Parliament by Lord Harris in 1975. https://parliamentarian/historic-hansard/commons/1978/apr/06/subversion-definition

[3] At least two officers, Bob Lambert and Mark Kennedy, ignored this.

[4] https://powerbase.info/index.php/Douglas_Edwards_(alias)

[5] See: https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Wilson-v-MPS-Judgment.pdf

About the author:

Chris is part of the organisation the Undercover Research Group, which began by supporting those activists most effected by the surveillance described here – and worked piecing together the fragmentary and limited evidence that was in the public domain before the Undercover Policing Inquiry began. Now, with thousands of documents and hundreds of hours of testimony available, they work to assist activists in the inquiry, by collating and summarising this huge and unprecedented release of information detailing the workings of the secret state.