2011 housing benefit reform was a false economy

2011 housing benefit reform was a false economy

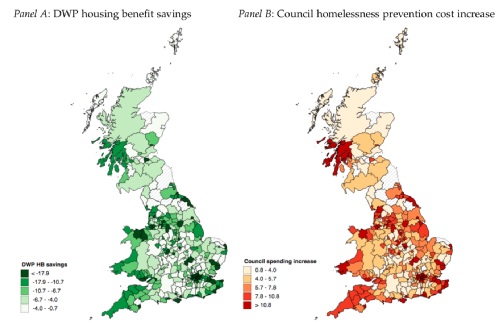

Thursday 27 Feb 2020Government reforms to housing benefit introduced in 2011 were intended to save the public purse hundreds of millions. But far from saving money, the change in policy simply shifted burdens to local councils: for every pound central government saved in housing benefit, local authority spending on temporary housing costs went up by 53p.

In their new paper, Housing insecurity, homelessness and populism: Evidence from the UK, Dr Thiemo Fetzer, Srinjoy Sen and Dr Pedro da Souza of CAGE also show that the cuts had substantial human costs, causing a significant increase in evictions, individual bankruptcies, a temporary increase in property crimes and a persistent increase in households living in insecure temporary accommodation, statutory homelessness and actual rough sleeping.

Cost-Benefit Analysis: Implied fiscal savings to central government from lower housing benefit versus higher council spending on for temporary housing and homelessness prevent - units measured in in £ per resident household

From April 2011 onwards, the Local Housing Allowance – the reference point for the calculation of housing benefit - was cut from covering the median of rents within a local housing market to only cover the 30th percentile. In addition, any excess payments were immediately cut. Throughout the UK, this cut affected nearly 1 million households in the private rented sector – constituting around 5.1% of all households or 25% of all households in the private rented sector.

Exploring a range of official and individual level survey data sources to establish the economic and social impact of this change, the authors find:-

· on average, households in the private rented sector lost £600 per year, but in parts of the UK with high housing costs the cut was significantly more.

· For example, across districts the financial loss among claimants living in 1-bedroom flats ranged from £260 - £1,612 per year; for claimants in 3-bedroom flats, the losses ranged between £364 - £3,900 per year

· as a result of the cut, forced evictions and repossessions in the private rented sector rose sharply by 22% after the cuts were implemented

· the number of households living in council-provided temporary accommodation rose by 17.8%

· statutory homelessness rose by 13.2% and actual rough sleeping increased by up to 50%

· the increase in statutory homelessness is driven by a sharp rise in working-age adults, families with children and single parents losing their home due to being evicted

· theft from persons and burglaries rose by 25% in the years immediately following the cut

The paper contributes to a growing body of literature on the effects of insecure housing and homelessness, the role of the welfare state in the provision of housing, and the relationship between housing and democratic participation.

Dr Fetzer commented: “Our study shows that this has been a very costly social policy choice both in the short term and in the long term.

“In the short term councils have had to increase spending to meet their statutory obligations in addressing and preventing homelessness. As councils have limited means of raising revenues, let alone issue debt, they are left with cutting services elsewhere to pay for these extra costs.

“The reform’s intention was to protect public welfare budgets from the spiralling cost of private sector rents in much of the UK. This was done by lowering and ultimately decoupling local housing allowance from local rental markets.

“This shifted the burden on to local councils, that, in order to meet their statutory obligations for homelessness prevention, in many cases, had to end up renting private owned accommodation at market rents to house benefit claimants -- an increasing share of which is in paid employment but can’t make ends meet.

“In the long term housing insecurity has pervasive effects on the achievement of children, it is a harbinger of poor health, and it increases the chances of being laid off from work.

“But we also found a negative effect on democratic participation. We found that electoral registration rates declined sharply in the wake of the changes - if you hardly can make ends meet and live in insecure accommodation, making sure your details on the electoral roll are up to date are unlikely to be a priority.”

Read the research

Thiemo Fetzer, Srinjoy Sen and Pedro CL Souza, Housing insecurity, homelessness and populism: Evidence from the UK, CAGE Working Paper no. 444, February 2020