Blog: The Climate Finance Dispatch

Pension funds and effective stewardship in the context of the climate crisis

Issue #11 | May 2024

Effective stewardship has been heralded as one of the key levers financial institutions have at their disposal to address the climate crisis. How realistic is our assumed model of stewardship in finance? We discussed this question with our colleague, Professor Yuval Millo, at the Warwick Business School. Yuval and his co-authors, Juliane Reinecke and Susan Cooper, interviewed pension trustees, their advisors and others in the pensions field about stewardship in the context of the climate crisis. Their research found that we might have a paradigmatic misalignment between our current model of stewardship, assumed especially in regulatory frameworks, and the reality of investment practices and dynamics. Their research calls not only to rethink regulatory considerations based on the current model of stewardship, but also to potentially develop a different mode of bottom-up coalition-building that goes beyond initiatives such as Climate Action 100+... Continue reading

A mobile ethnography of climate-related (financial) knowledge: the ‘plumbing’ and ‘flows of information’ underpinning green finance

Issue #10 | February 2024

In the last three years, we had the unique opportunity to look deep into the inner workings of green finance, attending hundreds of meetings, interviewing dozens of finance professionals, and scrolling through countless reports. How did we go about exploring green finance? And how does it help us to advance our understanding of green finance? In this blog post, we outline our research approach, calleda mobile ethnography, explain its main tenets, and how we implemented it in the context of our research. We reflect on what this approach makes visible in the context of the rapid evolution of green finance, and its potential for advancing our understanding of finance’s role in the ecological crisis... Continue reading

The tragedy before the horizon: avoided emissions and the need to decarbonise now

Issue #9 | December 2023

At the end of a ‘year of broken records’ and amidst a controversial deal at COP28, it is uncertain what the future holds for efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. One thing, it seems, is certain: that private finance remains endowed with a critical role in contributing to the decarbonisation of businesses and enabling a low-carbon economy. With a mixed track record of delivering on this role, financial institutions increasingly turn to ‘avoided emissions’ as a measurement of positive climate impacts from financial investments. But what exactly is the idea of avoided emissions and what is it actually good for? We argue that there are several conceptual, methodological and usage-related caveats that considerably limit the usefulness of avoided emissions as a metric for finance. Instead, we propose thinking about avoided emissions estimation as a research framework for understanding value chains and barriers to decarbonisation in the present, or in other words: to turn focus from the future to the present... Continue reading

A call for clarity: what is finance’s theory of (climate) change?

Issue #8 | September 2023

For years, an image has been cultivated of finance seemingly being able and wanting to play an active, if not decisive, role in combating climate change. From industry initiatives such as the CA100+, the PRI, the IIGCC, and the net zero alliances under the GFANZ umbrella to public sector institutions like the NGFS, and hybrid formats like the TCFD, finance has been setting itself up to meet one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century – but how is it going to deliver? And can it even know whether it is delivering? We argue that there is a need for greater clarity on finance’s theory of change of how climate goals can be achieved. Such clarity is pivotal for an evaluation of whether a given theory of change in fact delivers the desired outcomes... Continue reading

The Net-Zero Alliances: insights from a political theory perspective

Issue #7 | August 2023

In recent years, several net-zero alliances have sprung up in the financial industry. In this blog post, we view these net-zero alliances from a political theory perspective and ask how one might understand the kind of responsibility that financial institutions are taking when joining and participating in such alliances. Drawing on the political theorist Iris Marion Young, we suggest that financial institutions’ responsibility in climate change can be understood in terms of a “political responsibility” that aims to address structural injustices. This perspective entails two key insights for finance professionals and their stakeholders. First, the net-zero alliances can be understood as vehicles to achieve structural change in finance’s own practices and the practices of the economic entities that they finance. Second, to enable structural change, public deliberation that ensures the voices of external stakeholders are heard and taken seriously remains critical... Continue reading

Engagement: what can corporations and financial institutions learn from civil society organisations?

Issue #6 | June 2023

What can financial institutions (FIs) learn from civil society organisations when it comes to engagement? For Dr Felicia Liu,Link opens in a new window Lecturer in Sustainability at the University of York, the emergence of sustainable finance represents a reimagination of the objectives, the practices, and, ultimately, the impact of finance. To reimagine financial institutions as agents of change, Dr Liu looks into a space often neglected, i.e., the ways CSOs engage corporations and financial institutions. The Warwick Climate Finance Research team sat down with Dr Liu, and here she shares her insights from past and ongoing research, and her reflections on why reliance on current engagement models may be problematic... Continue reading

(Climate) Impact strategies for investors: what does academic research say about effective levers to achieve real economy impact?

Issue #5 | May 2023

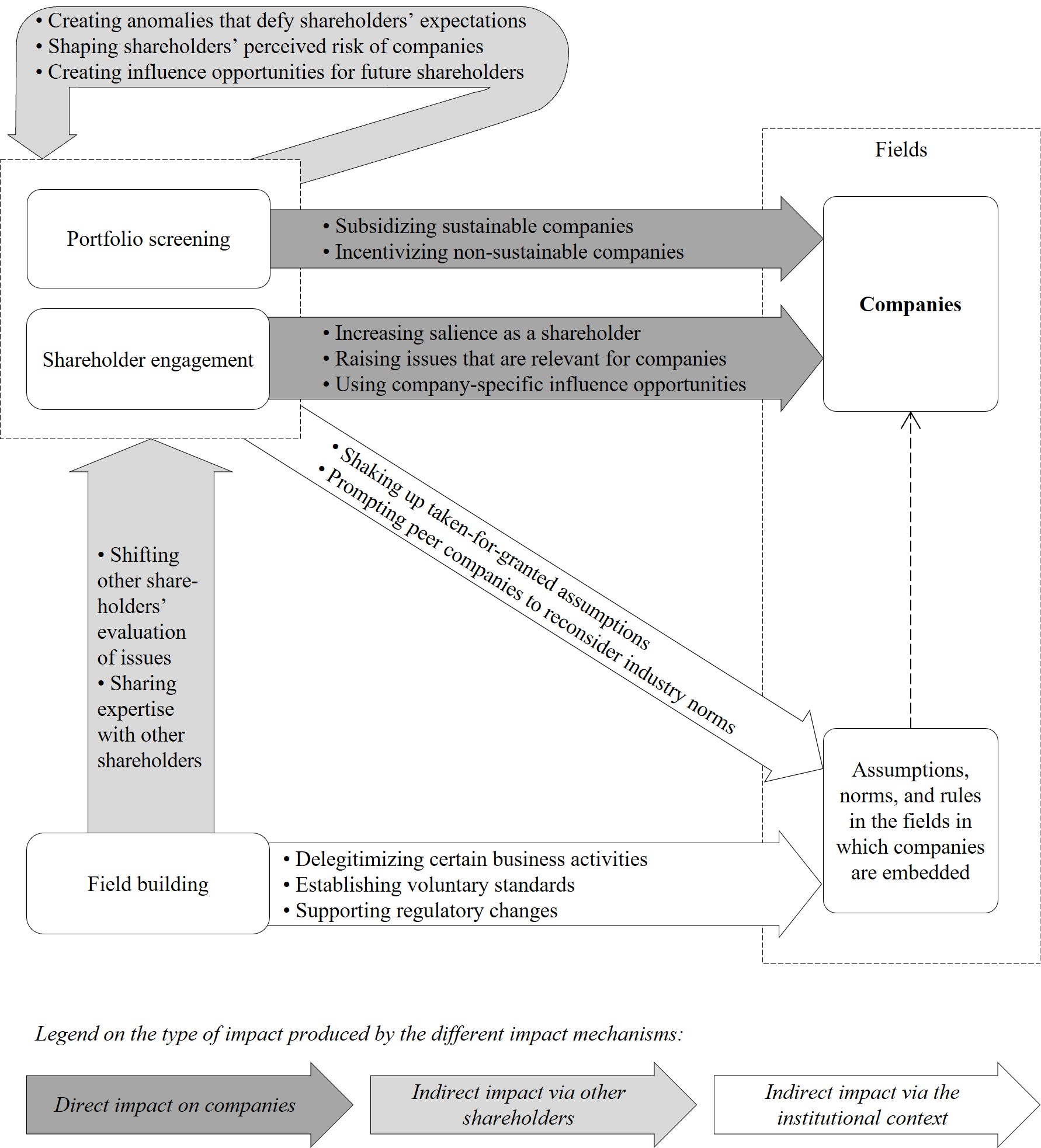

As investors move towards implementing and making progress on their interim and long-term net zero commitments, the question arises what the most effective levers are to achieve real world impact. We discussed this question with our colleague Dr Emilio MartiLink opens in a new window, Assistant Professor at the Rotterdam School of Management. Emilio argues that perspectives from disciplines other than financial economics are important in finding answers to the multi-dimensional question of shareholder impact. Whilst mainstream investors and financial economists focus on portfolio screening and engagement as impact strategies, Emilio and his colleagues identify a third, hitherto underappreciated strategy of ‘field building’. Even more importantly, he suggests that shareholder impact is a distributed process that arises through the interactions of different impact strategies. Thus, to come to a better understanding of how investors can achieve their net zero commitments, there needs to be a greater recognition and appreciation of how different impact strategies interact and build on each other... Continue reading

Net Zero target-setting for financial institutions: academic insights on “standards markets”

Issue #4 | April 2023 (edited June 2023)

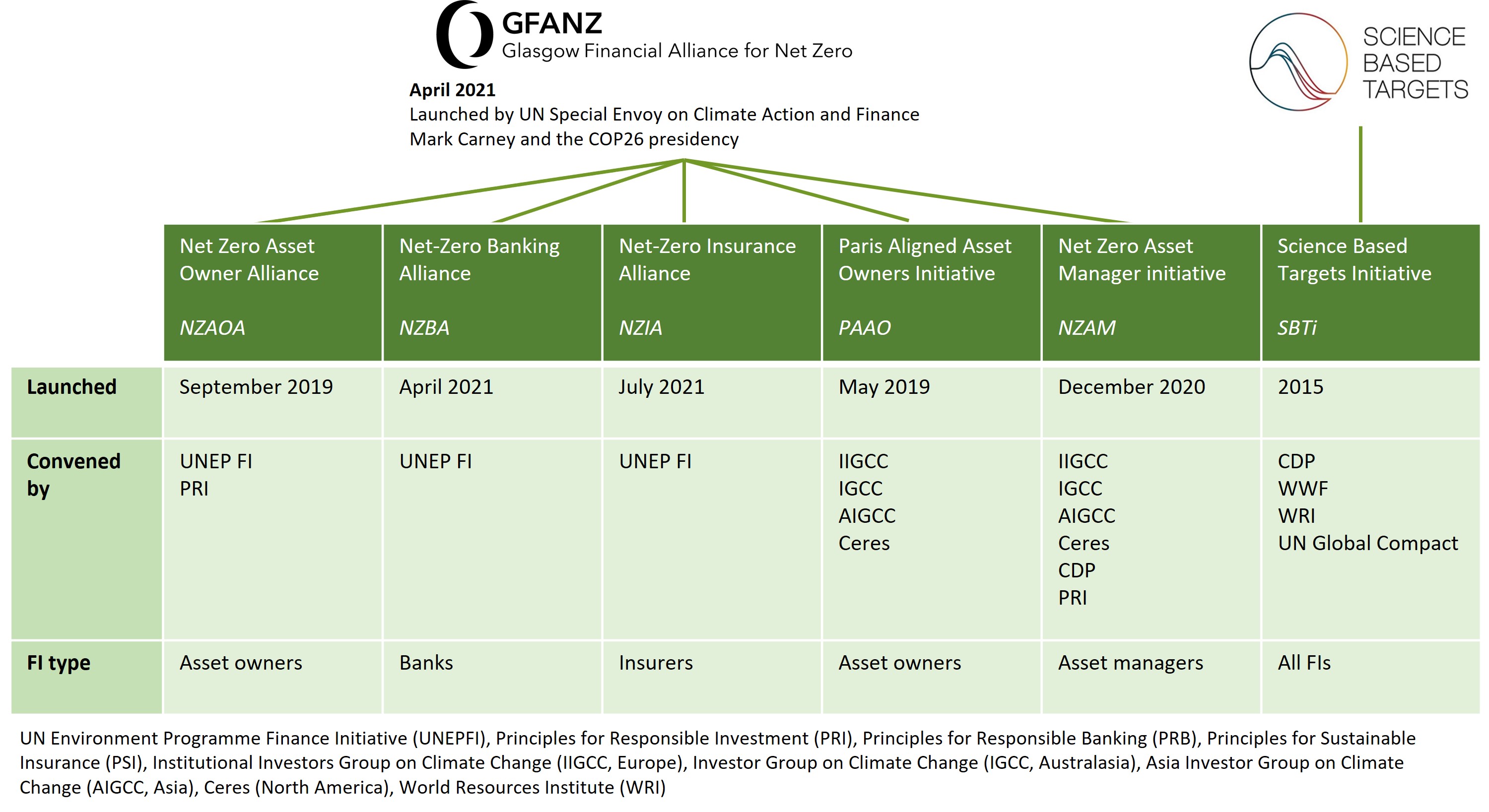

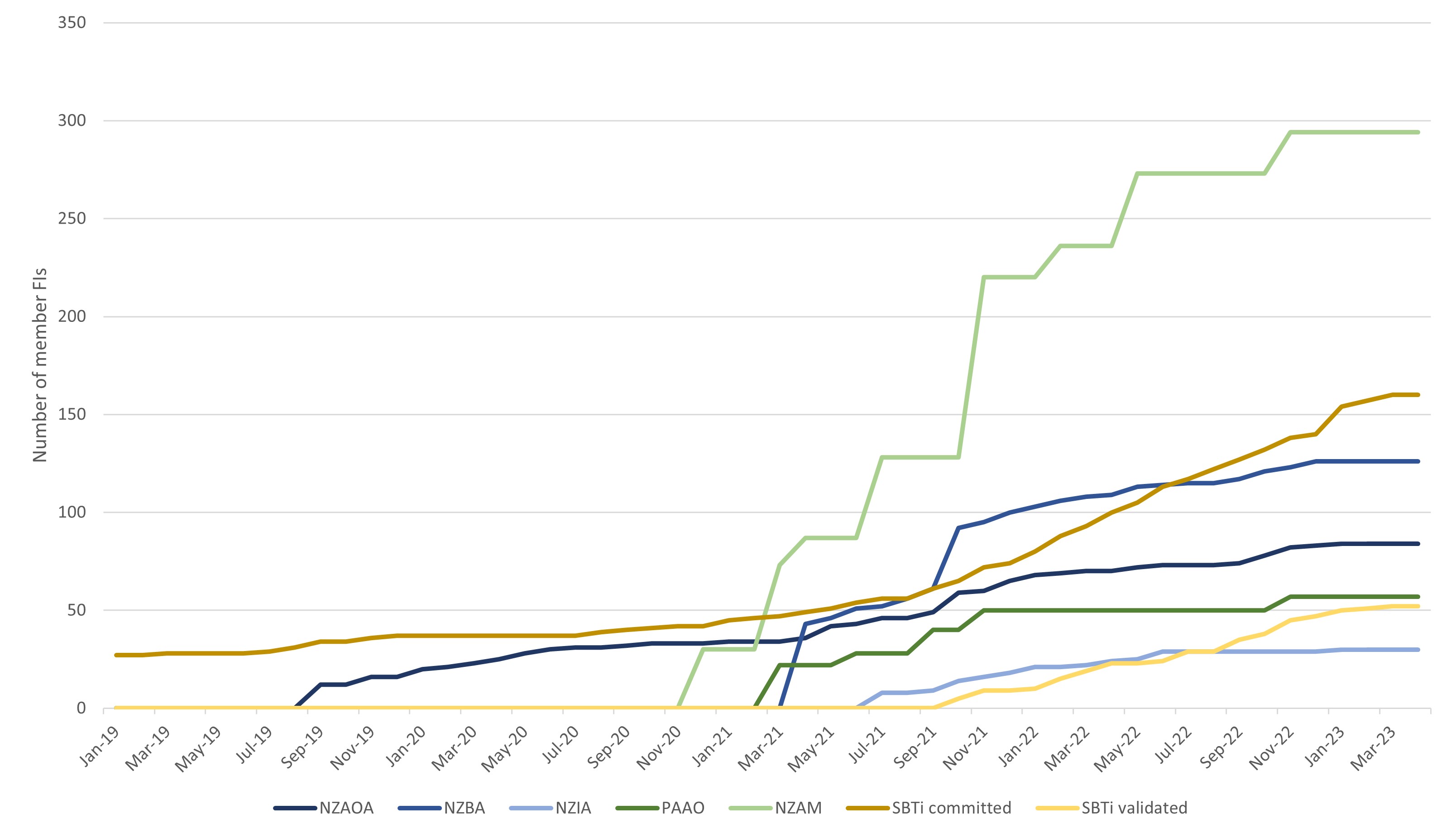

Can academic insights on “standards markets” help us make sense of developments around net-zero target-setting frameworks for financial institutions (FIs)? With looming regulation and mounting pressure from civil society groups, several net-zero initiatives or alliances have sprung up in recent years that have developed and continue to refine standards for how to set targets and achieve net zero by the year 2050. However, navigating the multiplicity of net-zero alliances together with their target-setting standards is a challenge. In this blog post, we provide an overview of the different alliances and standards. Drawing on academic insights about “standards markets” in other industries, we highlight some of the dynamics that underlie the emerging net-zero target-setting field for FIs, and we provide an outlook where the field might be heading... Continue reading

Implied Temperature Rise: mapping the main controversies

Issue #3 | March 2023

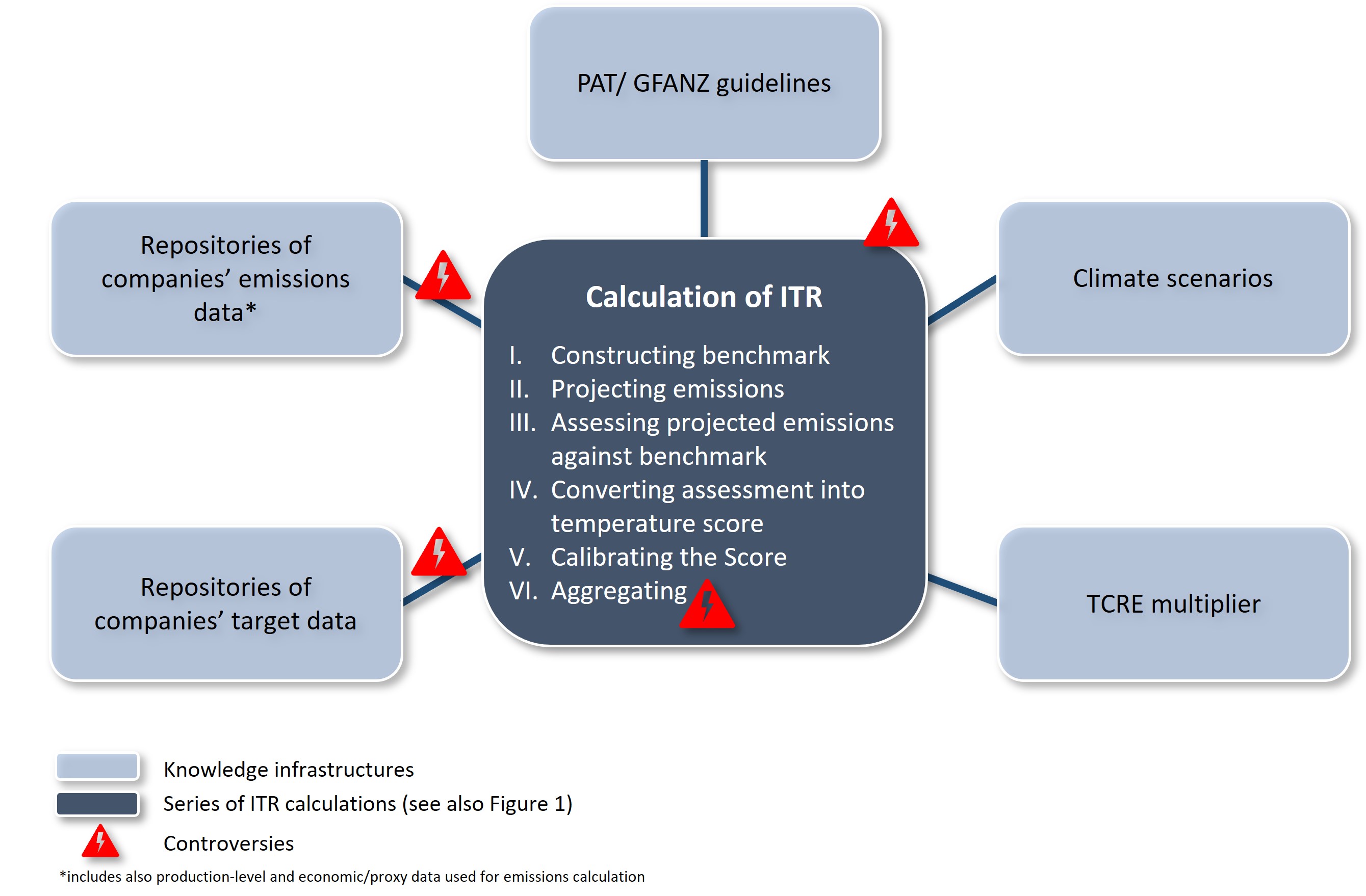

Implied Temperature Rise (ITR) tools that attempt to measure the temperature alignment of companies, portfolios and financial institutions are gaining momentum in the private climate finance space. ITR has become popular as it is a seemingly intuitive metric that captures the climate debate in one number and that allows communicating with various stakeholders. Most data and analytics providers now offer an ITR or temperature alignment solution. Many financial institutions feel they have to report a temperature score, and TCFD and GFANZ actively promote ITR. Yet, despite its wide support and appeal, ITR remains a contested and controversial tool. Our research uncovers that the main controversies surrounding ITR tools are rooted in the fact that a variety of different components that are not ‘ITR-specific’ are brought together to calculate a temperature score – a process we refer to as ‘stitching together.’ In this blog post, we map these controversies around ITR... Continue reading

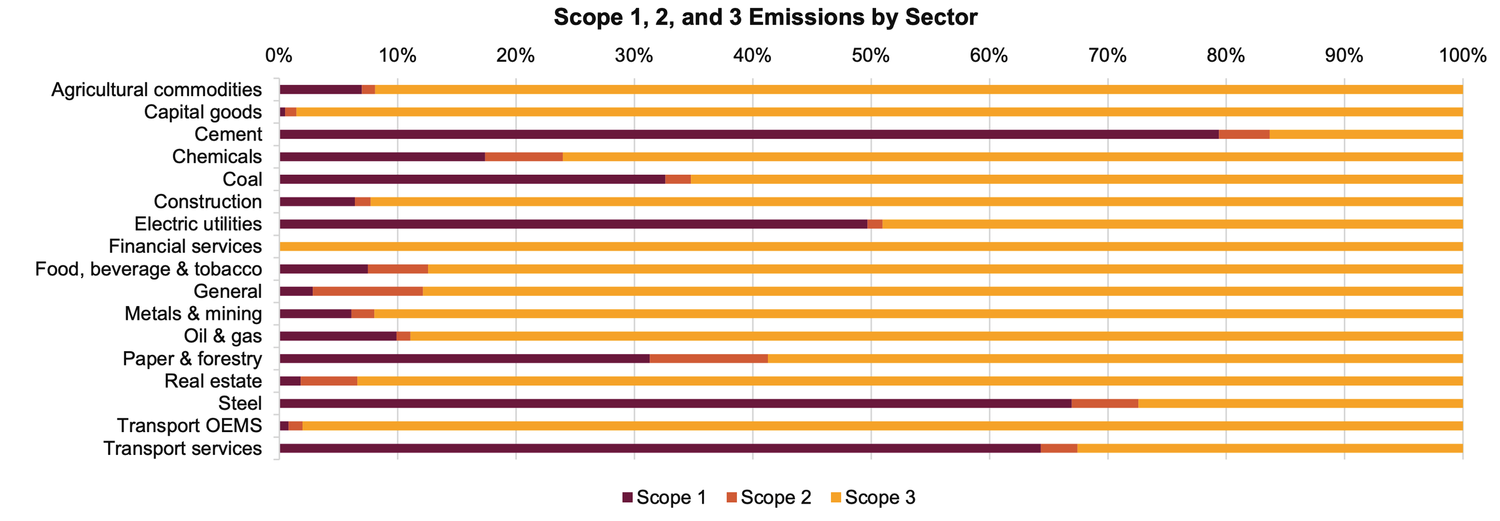

Scope 3 emissions data: is reported data really better than estimated data?

Issue #2 | February 2023

Scope 3 emissions estimates are most probably here to stay, but they need to become more transparent. Despite the prevailing preference in financial markets for reported Scope 3 emissions data over provider-modelled estimates, we need to acknowledge that reported Scope 3 emissions are also largely estimated. In fact, the differences and inconsistencies of estimates are often exacerbated between those of providers, and those of reporting companies. For the time being, financial institutions will need to live with estimates. However, in order for them to make more confident decisions and assessments there is room for improvement in understanding estimates of both providers and reporting companies... Continue reading

What is the Climate Finance Dispatch?

Issue #1 | January 2023

How are green finance professionals actually “doing” green finance? How do they work with data and tools to understand topics such as climate risk and climate alignment? These are the questions the Warwick Climate Finance Research project has been busy seeking answers to since 2020. The Climate Finance Dispatch blog is the platform where we are sharing updates on empirical findings, theoretical and methodological insights, and fascinating stories from the field. The blog is for anyone with an interest in emerging practices and tools in finance dealing with the climate crisis... Continue reading

Pension funds and effective stewardship in the context of the climate crisis

Effective stewardship has been heralded as one of the key levers financial institutions have at their disposal to address the climate crisis. How realistic is our assumed model of stewardship in finance? We discussed this question with our colleague, Professor Yuval Millo, at the Warwick Business School. Yuval and his co-authors, Juliane Reinecke and Susan CooperLink opens in a new window, interviewed pension trustees, their advisors and others in the pensions field about stewardship in the context of the climate crisis. Their research found that we might have a paradigmatic misalignment between our current model of stewardship, assumed especially in regulatory frameworks, and the reality of investment practices and dynamics. Their research calls not only to rethink regulatory considerations based on the current model of stewardship, but also to potentially develop a different mode of bottom-up coalition-building that goes beyond initiatives such as Climate Action 100+Link opens in a new window.

Yuval Millo & Katharina Dittrich

What inspired you to conduct research on pension funds and climate change?

“When I was researching sell-side analysts, one of the things that got me really interested is that in the investment field, there are many different temporalities. Some people think in terms of quarters, some people think in terms of five years, some people think in terms of one day. And they had terrible problems talking to one another. I knew that Juliane had done some work on temporality and I told her that many investors are not exactly clear about how to bridge those different temporalities. And then she said, ‘Well, what about pension funds?’, because she was interested in pension funds at the time. So we started looking at different temporalities with the idea that if you want to understand any organisation, but specifically organisations that deal with investments, you really need to understand how they bridge the different temporalities that people have.

So we started looking into pension funds and the proposed regulation of the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) that asks pension funds above 5bn GBP of AUM to report on what they did in relation to climate change – because climate change is a tricky case for time horizons. We looked at the comments that practitioners sent to DWP about the proposed regulation, and there were about 100 and something comments. And Susan Cooper, who was a PhD student at the time, took it on to start creating connections with these people: contract lawyers, data vendors, pension trustees, fund managers – basically a nice sample of the various actors in the field. And we started interviewing them.”

Your research suggests a significant mismatch between regulatory conceptions of stewardship practices and the situation you observed on the ground. What was it that you found?

“To be fair, it is not just the regulators. The regulators definitely embody this worldview, but it's a worldview that is very common. Just look at TCFD. The common understanding is that investors, because of their ownership of assets, can affect the activities of the companies whose assets they own. So if you own some Apple shares and you're a big investor, you can actually have a meaningful impact on what Apple does, and in our specific case with regard to Apple's climate change-related activities. We found out that it's not the case. I am going to mention two points, but there are others.

First, finance is not a chain where one link in the chain affects the others immediately after it. It really is a network that connects to others in all kinds of directions. Because of the networked nature of investment, your ability to affect from one side of the network on to the other side is very limited in many cases. It’s like you're trying to put a thread into a needle, but you're not doing it yourself. You're holding poles that are 10 meters long, and the poles are held by someone else and you're trying to direct them.

Second, pension funds and many other regulated funds have to take on advisors because the regulator knows that the trustees do not necessarily have the expertise relevant to investing. Now, it is assumed implicitly that because you're the owner, everyone else follows your commands and wishes. That’s not how it works. The advisor is an expert and trustees really rely on them for their input and they often lack the knowledge, especially on complex ESG issues, to challenge the advisor. In addition, we saw that the advisors take into account the pension funds’ risk management and so they offer them stable, safe, financial products, and these products tend not to be green, because green products are new, and therefore less stable, more risky, everything else held constant.

So, the main finding is really: we are using the wrong model of stewardship. Potentially we have a kind of paradigmatic misalignment: we are using the paradigm that used to exist maybe in the past, to describe and understand an investment world that is very different now.”

So what do your insights mean for pension funds and policymakers?

“I think many people know about this. They’ve been doing this for years. So I guess practitioners should be really honest, internally and externally, about their ability to be effective stewards. Are we as effective stewards as we should be? Then there are two things: First, the top-down regulatory paradigm is not very effective in working for climate mitigation and adaptation, because it exists in the way it is currently regulated. Do pension funds become greener, and the companies and all that? Not really. So, we probably need to think about a different regulatory framework for stewardship. Second, we need to think about some kind of a bottom-up approach, starting to work like social movements to politically making connections and creating political communication. Let's call it collective action sort of, but different from initiatives like Climate Action 100+. We need investors and others to form amoeba-like coalitions among themselves, but also with other types of actors, such as NGOs. These coalitions also need to consider the challenge that so much of ownership relations are tied up in passive instruments and asset management, which make intentional action very difficult.”

Issue #11 highlights

- What inspired you to conduct research on pension funds and climate change?

- Your research suggests a significant mismatch between regulatory conceptions of stewardship practices and the situation you observed on the ground. What was it that you found?

-

So what do your insights mean for pension funds and policymakers?

A mobile ethnography of climate-related (financial) knowledge: the ‘plumbing’ and ‘flows of information’ underpinning green finance

In the last three years, we had the unique opportunity to look deep into the inner workings of green finance, attending hundreds of meetings, interviewing dozens of finance professionals, and scrolling through countless reports. How did we go about exploring green finance? And how does it help us to advance our understanding of green finance? In this blog post, we outline our research approach, called a mobile ethnography, explain its main tenets, and how we implemented it in the context of our research. We reflect on what this approach makes visible in the context of the rapid evolution of green finance, and its potential for advancing our understanding of finance’s role in the ecological crisis.

Katharina Dittrich & Matthias Täger

Ethnography has a long tradition in the social sciences, in particular in anthropology and sociology. It is a way of approaching empirical phenomena through first-hand experiences, i.e., through participating in the social life of a particular group of people or an organisation and understanding what people do and experience on a day-to-day basis. Participation in meetings, shadowing staff members as they go about their work, interviewing them about their experiences, and reading their documents are all part of gaining that first-hand experience (Atkinson et al., 2007).

Traditionally, ethnography focuses on a single site – a single team, firm or community – but as social phenomena grew in complexity and scale, this focus on a single site no longer worked. Instead, new approaches to ethnography known as ‘mobile’ ethnography emerged (Marcus, 1995). A mobile ethnography prioritises the phenomenon of investigation and traces it closely as it evolves across multiple locales, and sometimes indeed around the entire globe. Take for example the work of Paula Jarzabkowski, Rebecca Bednarek, Laure Cabantous and others in their team on the practice of risk trading in the reinsurance industry. They traced the making of reinsurance deals from the trading floors in London to industry conferences in Monte Carlo to traders’ desks in Bermuda, continental Europe and Singapore (Jarzabkowski, Bednarek, & Cabantous, 2015). What these and other studies have in common is that they trace the connections, associations and putative relationships across multiple sites by following objects, concepts or people as they move.

The result of following a phenomenon as it moves across sites is that the object of study is emergent because the contours, sites and relationships are not known beforehand. The choices ethnographers make about where to start, and which connections to (not) follow will shape what becomes the object of study. In addition, the broader context in which local interactions happen, often referred to as ‘the system’ or the ‘global,’ is not considered an externally given frame independent of the many ‘locales’ but rather a dimension that emerges from the relationships amongst multiple sites. Finally, whereas in traditional ethnography, the researcher understands phenomena from a particular perspective, e.g., the local population, the ethnographer here shifts to a mobile positioning and a commitment to “see and see from these [multiple] positions critically” (Haraway, 1991).

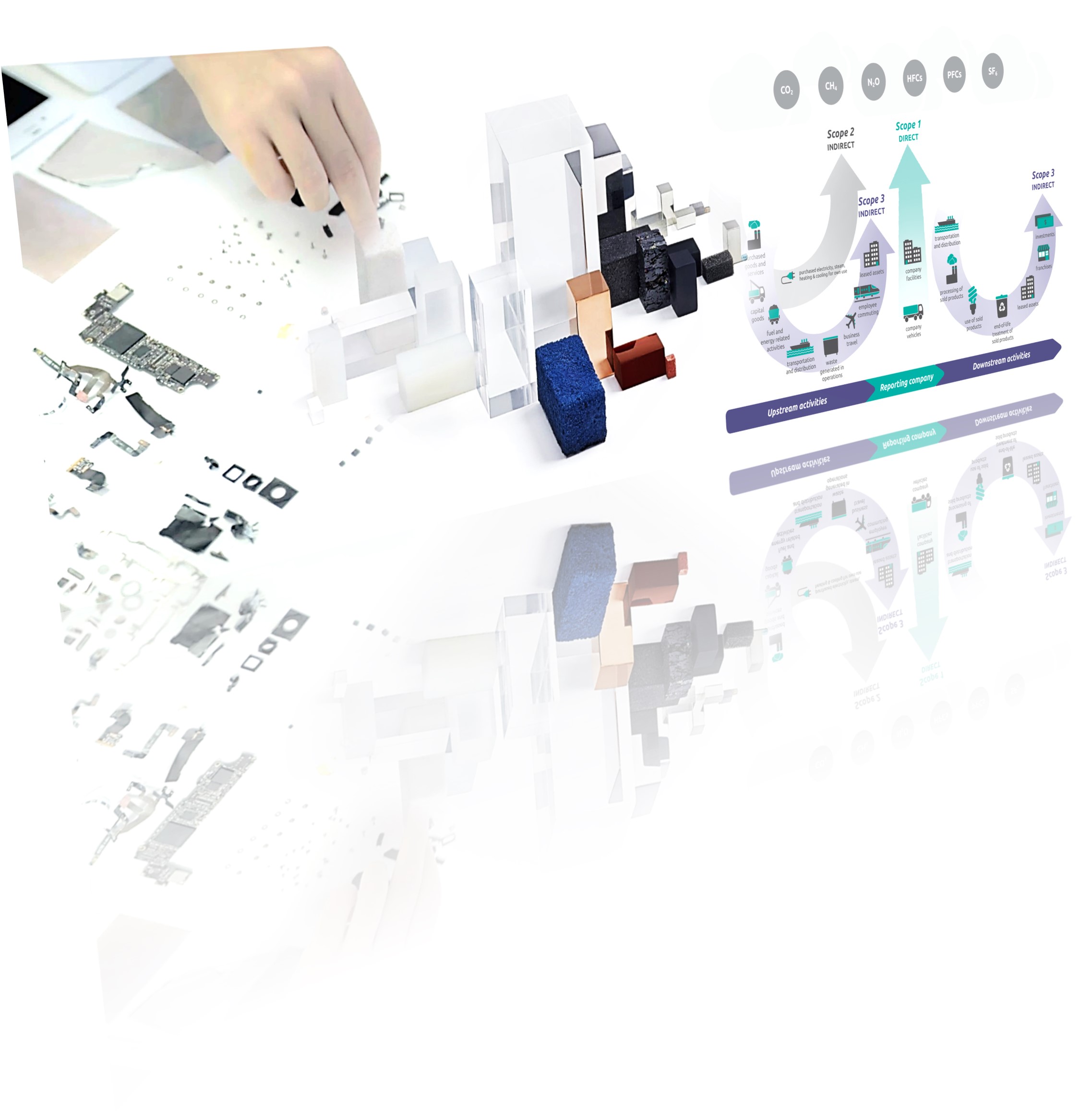

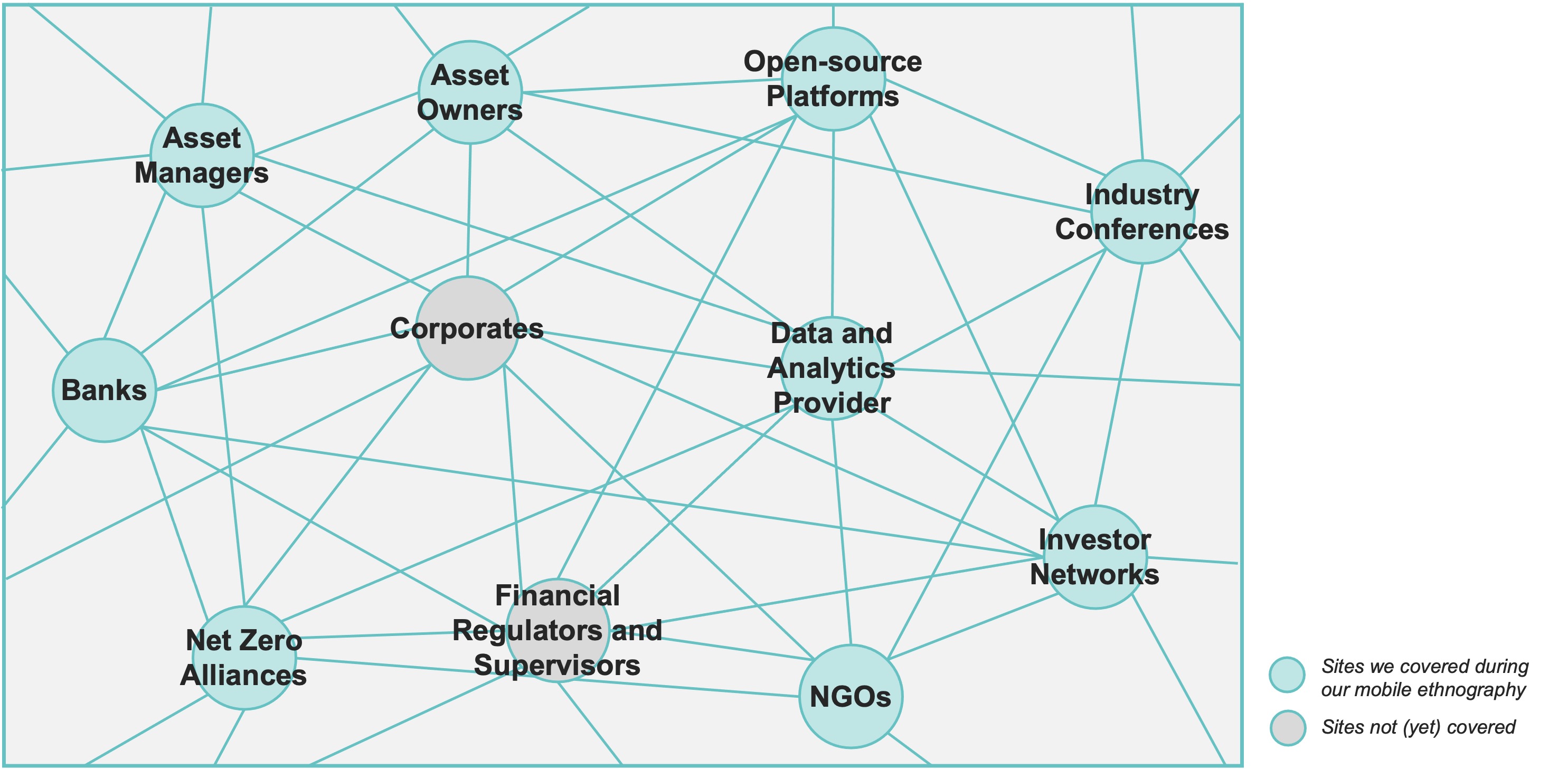

A mobile ethnography of green finance

Green finance, of course, is a phenomenon that stretches across many different locales – from corporate reports of CO2 emissions and other climate-related information to data collection teams at service providers, ESG professionals and risk managers at asset owners, portfolio managers at asset managers, and relationship managers and compliance officers at banks; from finance professionals at NGOs to policy analysts at investor networks, support staff at net zero alliances, and decision-makers at financial regulators and supervisors. It is also a phenomenon that has rapidly evolved in the last few years, from developments of private standards and public regulations (e.g., TCFD, EU Taxonomy, CSRD and the latest IFRS S1 and S2) to market developments (e.g., birth of the net zero alliances, and mergers and acquisitions in the analytics market) to societal developments (e.g., the ESG backlash).

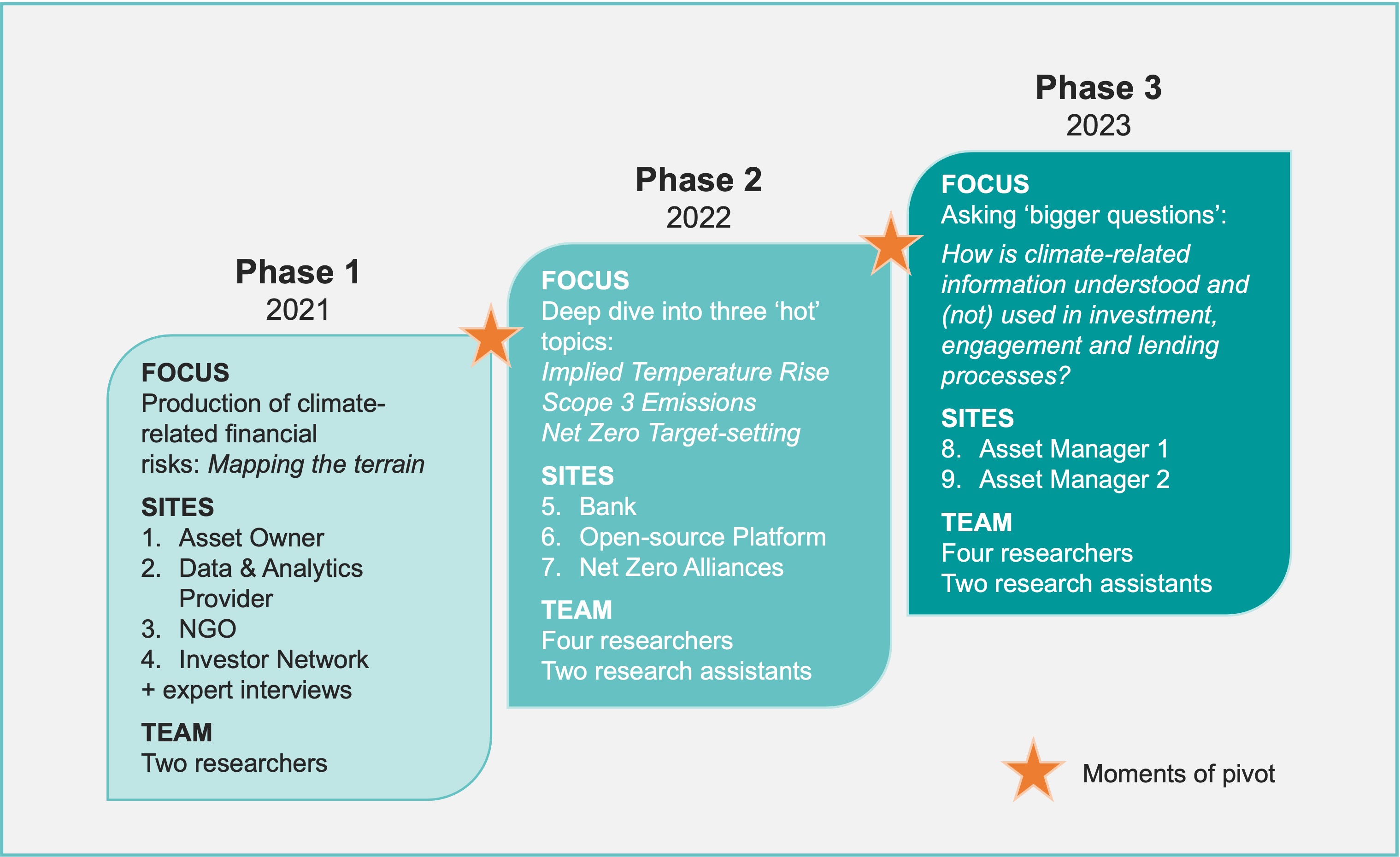

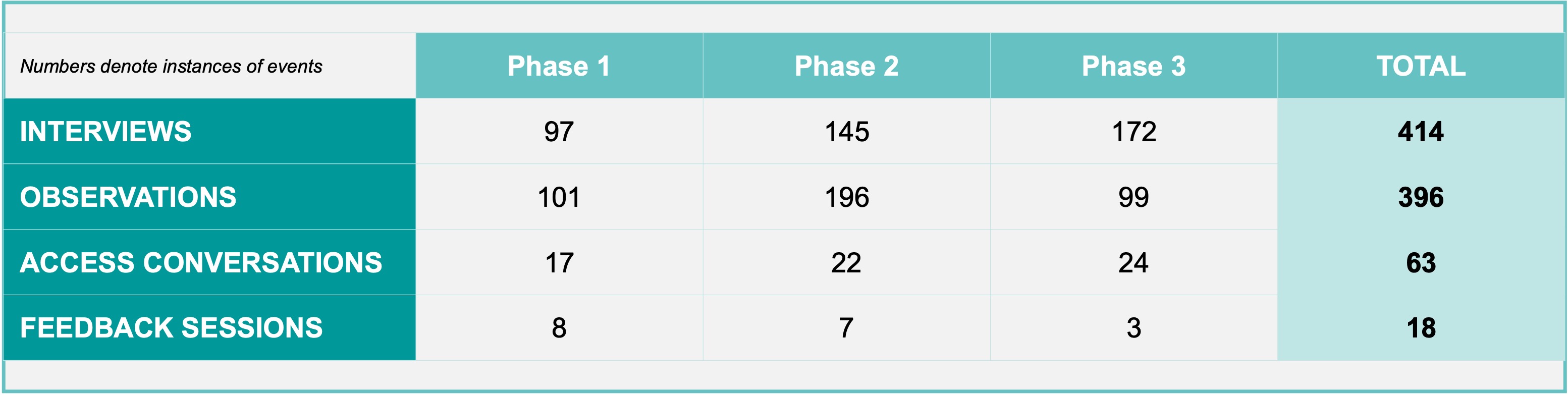

To grasp this complexity and rapid evolution is a formidable challenge for any ethnographer intent to understand what is happening on-the-ground in green finance. We approached this challenge by splitting our data collection into three phases. Each phase lasted approx. one year and consisted of eight to nine months of in-depth fieldwork, an intermediate analysis, and crucial moments of pivot to define the focus for the next phase. In this way, we were able to account for both the unfolding developments in the field as well as our emerging insights.

Phase 1 – Mapping the terrain: We started out in early 2021 as a team of two researchers[1] wanting to understand how climate-related financial risks were produced on-the-ground. In our efforts to get close to what finance professionals do on a day-to-day basis we selected four different sites: an international asset owner, a leading data and analytics provider, an NGO, and an investor network. We also talked to a range of experts outside these four organisations that were recommended to us. As we withdrew from this first phase of fieldwork, we realised that what connected the efforts across these different sites was a focus on measurement and knowledge production in the form of collecting and curating data, developing metrics and establishing frameworks thatprovide technical guidance on how to engage with climate change. In this context, the boundaries between climate risk and climate impact blurred because data and metrics could be used for either purpose. Instead, our object of inquiry became the work on what we started to call ‘knowledge infrastructures,’ i.e., the infrastructures in the form of data repositories, metrics and frameworks that provide the basis for financial institution’s understanding of climate change.

Phase 2 – Deep dive into three hot topics: At the beginning of 2022, we decided to delve into three topics that were particularly prominent in the efforts to build knowledge infrastructures at the time: Implied Temperature Rise (ITR) as a metric, the measurement of Scope 3 emissions of investee companies and clients, and net zero target-setting protocols. We followed the connections that had started to emerge in Phase 1 to the different net zero alliances, to an open-source platform, and to a bank, and deep dived into the complexities and challenges of evolving knowledge infrastructures in the pursuit to provide ‘better’ data and analytics. To cover these additional sites, our team also expanded to four researchers and two research assistants1. At the end of this Phase, we asked ourselves what representations emerge from this intense form of knowledge production about the relationship between finance and climate change.

Phase 3 – asking the ‘big questions’: The fieldwork in Phase 1 and 2 focused on the production of knowledge and information itself; in Phase 3 we turned our attention to how climate-related information is understood and used (or not) in investment, engagement and lending processes. Whatrealities does climate-related information constitute for finance professionals and with what consequences? To accomplish this shift in attention, we also expanded our data collection efforts to two asset managers. As our data collection efforts expanded to other sites in Phase 2 and 3, we reduced our engagement with some of the initial sites. Whilst Phase 3 was the last phase for our research for now, it made very clear that there is at least one other connection that we need to follow-up in future research, i.e., the connections with the work of financial regulators and supervisors.

The ‘plumbing’ and ‘flows of information’ underpinning green finance

So, what have we learned by following particular connections, and travelling across sites as opposed to spending in-depth time at only one or two sites? Our research makes visible what might be called the ‘plumbing’ and the ‘flows of information’ underpinning green finance: after all, the information that is produced and used in financial markets is supposed to shape where capital goes. What we have learned is how climate-related information flows through the various repositories, reports and databases across many different sites, and how that flow of information is shaped by the many pieces and parts put together to produce it, how leakages in the ‘plumbing’ are repaired and blockages are removed. We’ve observed the challenges in fitting together the many different pieces, and to continuously maintain them in the face of ongoing change. This ‘plumbing’ is important because the kind of information that flows will shape how “green” finance will become, and how it will be able to address our current ecological crisis.

In the coming months (and years) we will analyse what we have learned in our 400+ interviews and roughly 400 observations of meetings, workshops, conferences, and webinars. We will reflect on what our perspective might add to the understanding of green finance. What kinds of information do the current knowledge infrastructures make available, and what is missing? What kind of action or inaction do they facilitate? What are alternative ways of knowing that green finance could draw on? Stay tuned for what will come next.

References

Atkinson, P., Delamont, S., Lofland, J., & Lofland, L. (Eds.). (2007).Handbook of Ethnography. SAGE Publications Ltd.

Haraway, D. (1991). A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century. In D. Haraway (Ed.),Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature(pp. 149–181). Routledge.

Jarzabkowski, P. A., Bednarek, R., & Cabantous, L. (2015). Conducting global team-based ethnography: Methodological challenges and practical methods.Human Relations,68(1), 3–33.https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714535449

Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography.Annual Review of Anthropology,24(1), 95–117.

[1]The team is an additional dimension of the mobile ethnography that we cannot cover in this blog post, but will aim to address in future posts.

The tragedy before the horizon: avoided emissions and the need to decarbonise now

At the end of a ‘year of broken records’ and amidst a controversial deal at COP28, it is uncertain what the future holds for efforts to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees. One thing, it seems, is certain: that private finance remains endowed with a critical role in contributing to the decarbonisation of businesses and enabling a low-carbon economy[1]. With a mixed track record of delivering on this role, financial institutions increasingly turn to ‘ avoided emissions’ as a measurement of positive climate impacts from financial investments. But what exactly is the idea of avoided emissions and what is it actually good for? We argue that there are several conceptual, methodological and usage-related caveats that considerably limit the usefulness of avoided emissions as a metric for finance. Instead, we propose thinking about avoided emissions estimation as a research framework for understanding value chains and barriers to decarbonisation in the present, or in other words: to turn focus from the future to the present.

Julius Kob, Katharina Dittrich & Matthias Täger

In finance, avoided emissions represents the idea that investments from financial institutions could be tied not only to their assets’ carbon emissions – and hopefully pressure to their reduction – but also to the potential emissions that may be prevented by new products in existing value chains. Especially in future situations of increased carbon prices, these would make sense not only environmentally but also economically. This referral to future states of new products and business models, however, requires not only imagination but also deep understanding of the affected present value chains. And although so-called ‘climate solutions’ need to be developed and scaled, and imagining these solutions’ future potentials for low-carbon economies can be valuable, avoided emissions’ concept, methods and usages present several caveats we will discuss here. Chiefly, however, it is the current state of value chains that require rapid decarbonisation through emissions reductions now, which must be pursued with urgency. Here, avoided emissions are of little immediate help, but the process of estimating them can help investors deepen their understanding of present value chains and the barriers to current emissions reductions: avoided emissions for financial use should not be understood as yet another metric for possible futures but as a new heuristic to support decarbonisation in the present.

What is the idea behind calculating ‘avoided emissions’?

Avoided emissions can be understood as emissions that are not emitted because a specific product or service has been used (see e.g., WRI). Important, at least from a life-cycle analysis perspective, is that these emissions have to have ‘not occurred’ outside the product’s or service’s own value chain, otherwise one would understand these simply as their own emissions reductions. An example of an instance of avoided emissions are more efficient insulation products that reduce energy for heating in new or retrofitted buildings, where the emissions avoided by the insulation product occur in the value chain of housing and not in that of insulation products. Importantly, the insulation product does not decarbonise the present source of the emissions in question here, i.e., the emissions produced from burning fuel in the boiler and, of course, those emitted in producing the fuel in the first place. In fact, heating emissions could rise, e.g., from an increase in residential buildings, while simultaneously increasing insulation-related avoided emissions could be claimed.

Approaches to calculating avoided emissions vary heavily and can be cases or combinations of e.g., life-cycle analyses, corporate or project accounting, or consequential time series approaches. Avoided emissions approaches have been around since the 1990s but have received increased interest in the financial industryLink opens in a new window especially in the last few years[2].

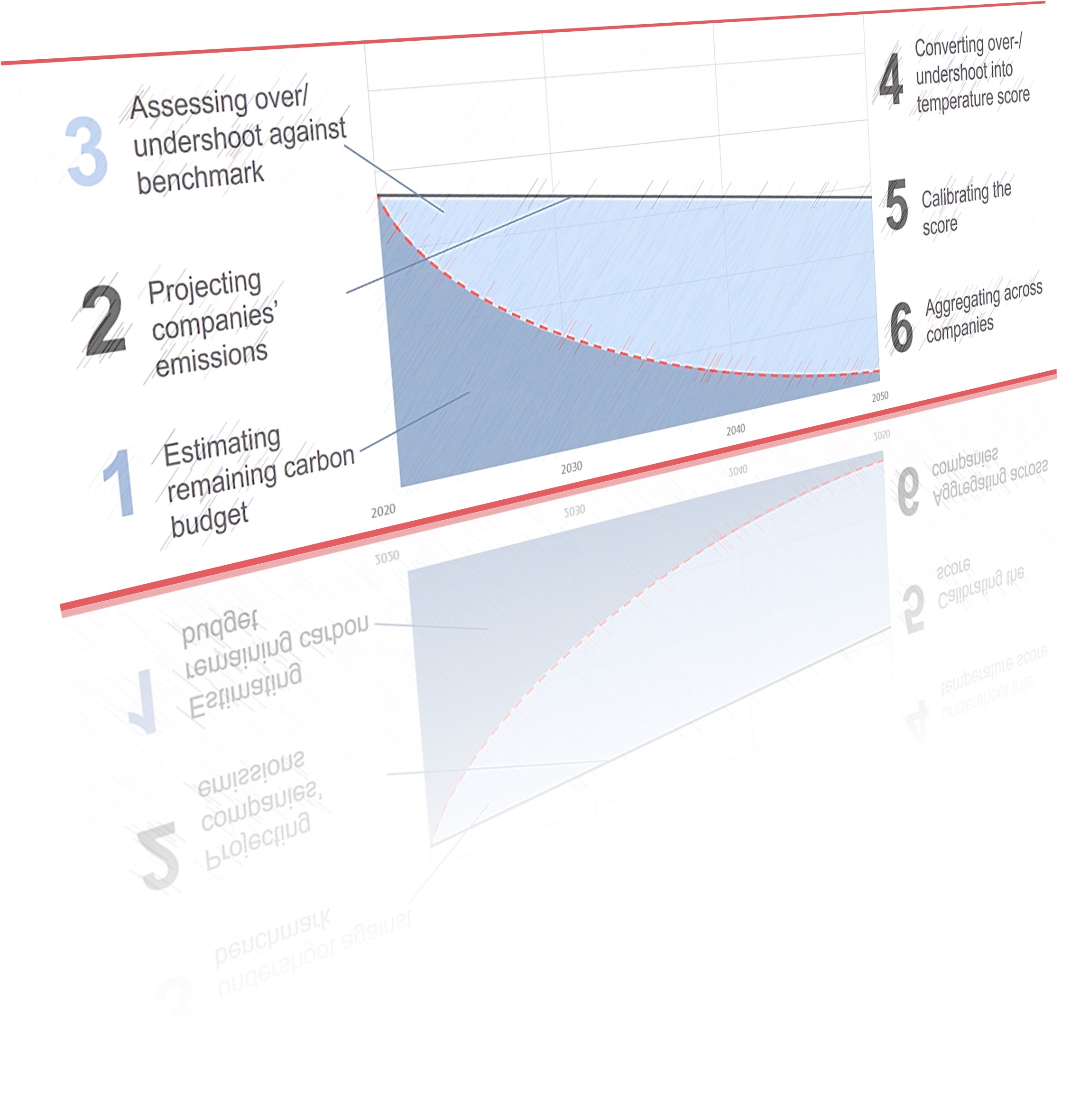

Admittedly simplified here, calculating avoided emission usually requiresLink opens in a new window (a) to define the product or service and the boundaries of its own value chain and wider system it is embedded in, and in close dependency (b) to define the baseline to which to compare it, e.g., the product or service that would potentially be replaced and the system in which the alternative may avoid emissions. On this basis (c) the applicable emissions factors related to the different emission sources need to be chosen (for the example above, for instance, the emissions per KWh of a 2010 gas boiler). Next, (d) the market share of the product or service needs to be estimated, (e) the emissions of the product or service and baseline product calculated, and finally (f) the solutions emissions subtracted from the baseline emissions and the attribution in the change of the value chain determined.

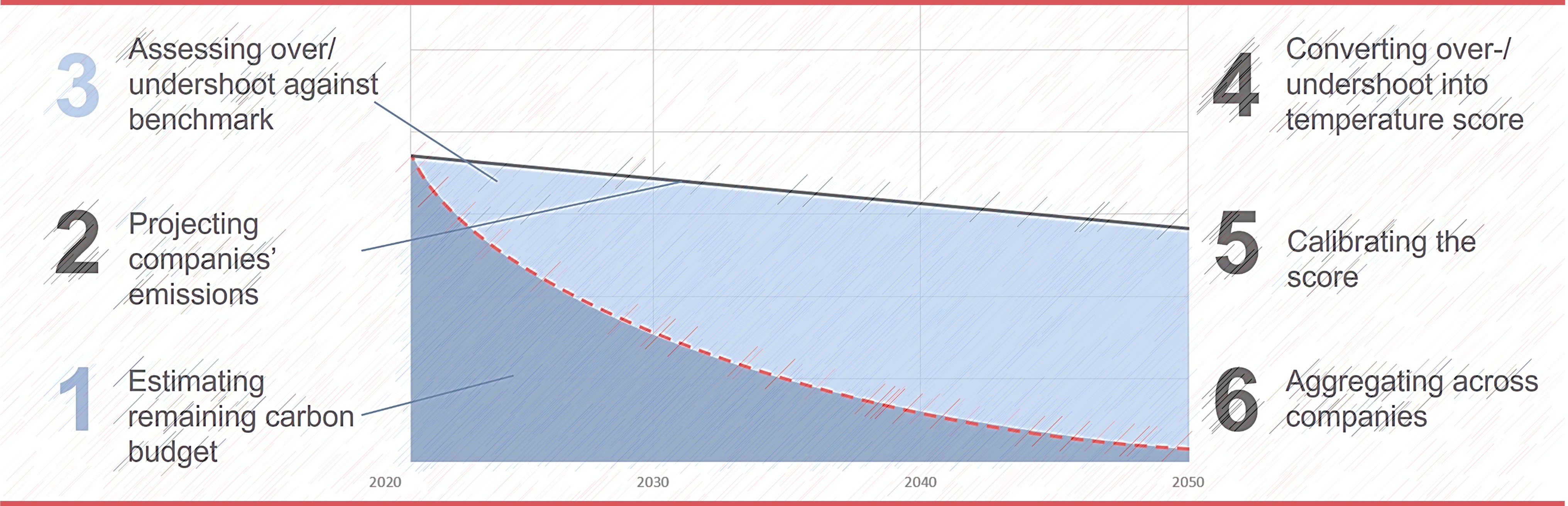

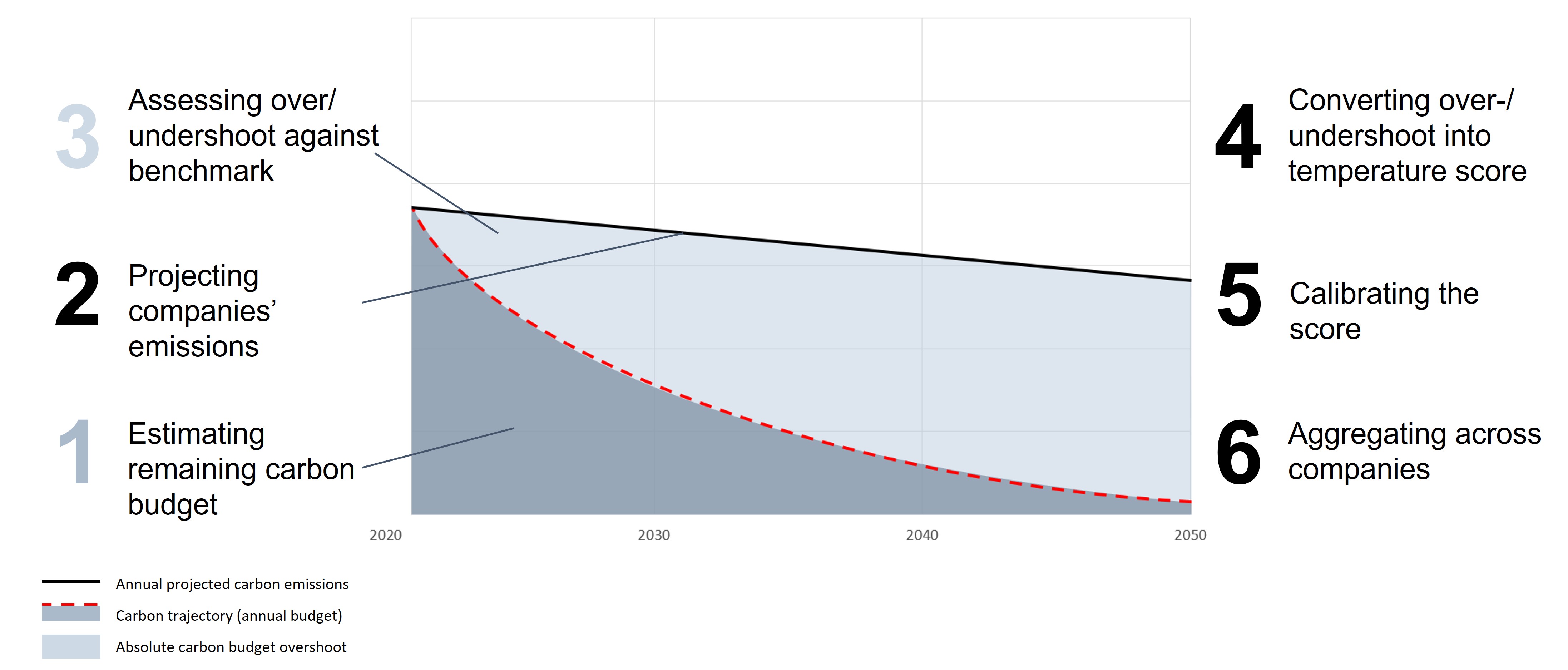

Figure: Steps for calculating avoided emissions

Source: Warwick Climate Finance Team, adapted from a diagram by Cleantech ScandinaviaLink opens in a new window

Although an impact measure is understandably attractive for financial institutions, we see three types of caveats in applying avoided emissions in an investment and portfolio management context, that limit at least the more formal and mechanistic uses of avoided emissions, but we see considerable benefits for its use in fundamental research and for gaining deeper understanding of value chains and wider systems with respect to transition needs.

Conceptual caveats: Avoided emissions are conceptually distinct from emissions reductions

Today, many different terms for avoided emissions are in circulation, such as ‘comparative emissions’, ‘climate handprint’, or ‘consequential emissions’, which already hints towards conceptual ambiguity. Recently gaining particular popularity is the term ‘Scope 4’ emissions.[3] While Scopes 1-3 carbon emissions have been established as a reference point – albeit far from flawless – for climate risk, avoided emissions is gaining attraction as a metric signifying climate opportunity.

Although appealing to some, it would be detrimental to consider both metrics as ends of the same scale which can be measured against one another – we therefore consider especially the ‘Scope 4’ terminology as misleading. Carbon footprints, i.e., Scopes 1-3, point to the increasingly dire need for emissions reductions: the rapid decarbonisation of existing industries and value chains in a shrinking carbon budget, which avoiding emissions cannot fulfil – avoided emissions only show a reduction in projected future emissions relative to a baseline, but they do not show whether that reduction is ‘enough’ or whether it is consistent with net zero. A former impact fund designer and ESG analyst we spoke to likened it to trying to consider not buying a pair of shoes as a gain in one’s wallet: you do not have more money, you just don’t have less than before not buying the shoes and still have to pay your monthly bills.

Climate solutions’ avoided emissions, although inhabiting an important place in the overall journey to a low-carbon economy, are different to carbon reductions and must not distract from the most pressing need to push and help investee companies to decarbonise, which can only be achieved where emissions are actually being emitted now within a concrete carbon budget. Avoiding emissions means the addition of a product or activity that helps emitting less than an existing status quo product or activity and the future promise of the latter’s substitution by the former.

Methodological caveats: Calculating avoided emissions is highly contextual

Conflation on the conceptual level, however, is not the only issue lurking, as the underlying approaches open up another dimension of caveats on the methodological level. There is by now a considerable number of different methodologies and approaches and guidelines, which differ to quite a degree from one another both conceptually and on the level of application. A recent project comparing 14 different avoided emissions approaches in depth finds huge variations of up to a factor of two from applying different frameworks and methodologies to the same product. So, the multitude of methodologies alone leads to an increased multiplicity of outputs.

More importantly, though, due to the specificities of products, processes and systems in and across value chains that could be thought of as avoiding emissions, determining avoided emissions is highly contextual and assumption-dependent. What is more, the contextuality of estimating and interpreting a product’s avoided emissions makes it incredibly difficult to compare avoided emissions between two different products – think of more efficient insulation products and ICT services for digital business meetings.

In practice, this means that financial institutions in their fundamental research will find various potential narratives for the current and future development of a company and product and their success a basis for their investment case. These perspectives will determine differently the solution and baseline definitions, and value chain change thesis, as well as the prognosis of the product’s potential market penetration. As we have observed at an asset manager in our research, the heavily assumption-driven factor of attribution, i.e., the degree to which a product may contribute to the assumed value chain change, has huge influence on the avoided emissions number in the calculation, second only to the even more assumption-driven growth prognosis of the company in question. The growth prognosis is a core competency of investment staff and thus depends also on the investment strategy, e.g., long-term versus short-term positions. Another very contextual and at the same time systemic assumption, for instance, is the temporal frame of a product and its growth saturation, e.g., house insulation products and a switch to electric heating in an increasingly renewable energy generation market, where the potential share of avoided emissions goes down the more its grid runs on renewable energy. Investors will have different assumptions on when such a saturation point (if at all) may be reached.

Usage caveats: Avoided emissions as a metric are problematic for disclosure, target-setting and standardised commercial products

Against this backdrop of both potential conceptual and methodological issues, the use of avoided emissions as a metric at financial institutions warrants a number of caveats. Fundamentally, due to the highly contextual nature of avoided emissions, the wide range of methodologies, and the various ways an analyst or investor constructs a product’s change-thesis, avoided emissions numbers do not lend themselves for direct comparison, not between companies using the same methodology and even less when calculated by different funds or different financial institutions. In the same vein, meaningful aggregation of avoided emissions on fund or portfolio level seems rather implausible. As a result, disclosing ‘avoided emissions’ on a fund level is problematic and also holds considerable greenwashing risks.

Due to the methodological challenges but even more to avoid the conceptual conflation mentioned further above, avoided emissions should not be used in net-zero target setting. Avoided emissions, although important, are changes relative to a projected baseline of future emissions and hence cannot be understood as immediate and , more fundamentally, absolute emissions reductions for decarbonisation, which are the core aim of setting objectives such as net zero by 2050 or earlier.

More generally, given the high degree of contextuality, a standardised methodology, although helpful, would produce outputs that still have to be assessed carefully. Also, the merits of producing such outputs would require discussions, especially concerning questions around attributing avoided emissions as actual impact from investments, for instance, in equity vis-à-vis private markets. But even then, the actual number of avoided emissions – and only on a company-level – can be understood as a systematically produced but only indicative illustration of the viability of a business model and an investor’s belief in its climate alpha. This is also an important reason why we would consider an off-the-shelf avoided emissions data product by data providers, akin to Scope 1-3 emissions data provision services, as highly problematic, because its very calculation is on so many levels tied to the concrete investment context. More importantly, though, it would prevent the primary benefit we see in the avoided emissions concept for financial institutions, which we will turn to now.

Avoided emissions as a research framework

Given the conceptual, methodological and usage caveats outlined above, the question is how to best use avoided emissions in finance. We propose that the concept of avoided emissions can yield considerable benefits when thought of as a heuristic. As a research framework for fundamental research, avoided emissions can bring a structured approach to a better understanding of companies’ potential contribution to a low-carbon economy – not to be conflated with a presently decarbonising economy, though. Especially investment staff, in addition to ESG specialists, can integrate a climate-specific perspective into their investment research and decision-making by engaging in avoided emissions estimation. As an impact analyst from an avoided-emissions focused impact fund told us, “the process [of computing the number] is more important than the number itself […] the output doesn’t matter so much”. In other words, it potentially allows an investment manager to understand the future development and changing role of both the product and the value chain in a dynamic transition context. For instance, not just the building insulation product but the entire low-carbon housing value chain and the barriers and potentials for decarbonisation of housing today, including but also irrespective of the product in question.

Even though avoided emissions as a number should not be conflated with absolute emissions reductions, as pointed out above, the insights from the analysis, nevertheless, can shed light on the current deficiencies and barriers that stand in the way of decarbonising value chains and wider systems from an investment perspective. In this sense, the insights from the process of calculating avoided emissions can feed not only into investment strategies around climate solutions, but into other strategies, such as engagement, where investors engage companies on their emissions reduction efforts because they have built a deeper understanding of value chains and the interconnectedness driving their decarbonisation. This connects to one of our other blog posts on finance’s theories of changeLink opens in a new window, in which we suggest that strategies employed by financial institutions must be integrated in a holistic and specific theory of change that ultimately leads to emissions reduction and a decarbonisation of industries.

Key takeaways and conclusion:

To summarise the above discussion, our main takeaways are:

- Avoided emissions is not the same concept as emissions reductions: it cannot substitute decarbonisation of existing industries, i.e., the reduction of absolute emissions in the present.

- Calculating avoided emissions is highly context- and assumption-driven: outputs cannot be compared across companies, analysts, fund strategies, portfolios or financial institutions.

- Contextuality of avoided emissions poses issues for use in finance: avoided emissions for target-setting, disclosure and standardised commercial products are misleading and pose greenwashing risks.

- Avoided emissions are a research framework: notwithstanding the positive influence of investments in climate opportunities that avoided emission calculations can support, given the urgency of emissions reduction, the main benefit of avoided emissions is to underpin deeper understandings of value chains and wider systems and the barriers to their actual decarbonisation.

In times of a thus far mixed track record of climate integration in finance, a ‘dynamic’ situation (to say the least) around climate policies and efficacies of transition efforts, a metric promising a positive impact measurement for investments would be very useful for many otherwise difficult tasks in private climate finance, such as in reporting, investing, marketing, etc. But the potential usefulness of a tool or a concept must not mask or outweigh its inherent issues and complications, and so the caveats around the metric of avoided emissions, such as those discussed above, should be taken seriously. Equally important and much more helpful is treating it explicitly as a heuristic that can serve to deepen an understanding and inform action around decarbonisation now. For avoided emissions to be helpful, finance needs to underscore the awareness of the primacy of sustained emissions reductions and recognise in this context the limitations and affordances of avoided emissions and the most effectful uses of the concept in financial practice. The cause of the tragedy lies before us and although keeping the horizon in sight is paramount, acting on it now by decarbonising value chains in the present is the most pressing task and finance must deliver its share in it.

[1] Conference: “The decade of sustainable finance: half-time evaluationLink opens in a new window” co-organised by MEP Paul Tang and QED, 14 November 2023, Brussels, Belgium.

Conference: "Shifting the Trillions - Financing the future economyLink opens in a new window", 22 November 2023, Berlin, Germany.

[2] Traces of the idea of avoided emissions can be found in the emergence of carbon markets, and more explicitly emerged at the latest in the context of project GHG accounting in the early 2000s. Especially the 2005 GHG Protocol’s Project Accounting ProtocolLink opens in a new window sought to provide a framework that could express the positive impact of climate change mitigation projects. Much has since been produced around approaches calculating avoided emissions across various sectors, with a noticeable uptake since the mid-2010s, including an often-cited framework for comparative emissions impacts of productsLink opens in a new window in 2019 by the World Resources Institute (who co-convenes the GHG Protocol). In the financial realm, especially multilateral development banks since 2015 have produced GHG accounting frameworksLink opens in a new window that include avoided emissions to enable assessing positive climate impacts of their development investments.

[3] Although the term ‘Scope 4’ emissions has been also used to described other aspects of climate impact, such as climate lobbyingLink opens in a new window.

Issue #9 highlights

- What is the idea behind calculating ‘avoided emissions’?

- Conceptual caveats: Avoided emissions are conceptually distinct from emissions reductions

- Methodological caveats: Calculating avoided emissions is highly contextual

- Usage caveats: Avoided emissions as a metric are problematic for disclosure, target-setting and standardised commercial products

- Avoided emissions as a research framework

- Key takeaways and conclusion

A call for clarity: what is finance’s theory of (climate) change?

For years, an image has been cultivated of finance seemingly being able and wanting to play an active, if not decisive, role in combating climate change. From industry initiatives such as the CA100+, the PRI, the IIGCC, and the net zero alliances under the GFANZ umbrella to public sector institutions like the NGFS, and hybrid formats like the TCFD, finance has been setting itself up to meet one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century – but how is it going to deliver? And can it even know whether it is delivering? We argue that there is a need for greater clarity on finance’s theory of change of how climate goals can be achieved. Such clarity is pivotal for an evaluation of whether a given theory of change in fact delivers the desired outcomes.

Matthias Täger, Katharina Dittrich & Julius Kob

In this blog post we review the strategies most commonly discussed and employed in private finance to address climate change. We summarise questions regarding their efficacy that we have encountered and discussed with various finance professionals during our research. In light of the diverse strategies in use and their respective underlying theories of change, we note that both on the level of the individual financial institution, and the level of the sector as a whole there is a need for greater clarity which theory of change is being pursued. The blog post thus formulates a call for action for finance to

a) clarify their theory of change and their strategies building on this theory to subsequently

b) device ways to continuously and systematically assess the plausibility of their theory of change and the efficacy of their strategies.

We believe that these steps need to be carried out by both alliances and other collaborative fora in finance as well as by individual financial organisations translating the collective theories of change and strategies into their respective context.

Finance’s theory of (climate) change

With climate-related initiatives and networks within finance being legion, it is not easy to develop a clear understanding of what the concrete goals are that finance is pursuing – or rather those actors within finance that are willing to actively engage with the issue of climate change. Formulations referencing ‘net zero’, ‘Paris-alignment’ or ‘financing the transition’ define wide target corridors open to ambiguity and often prompt debates about the meaning of these terms. Equally ambiguous are the theories of change according to which concrete strategies employed are assumed to reach stated goals and their respective plausibility and efficacy.

By theory of change we mean a coherent causal chain that logically connects actions and strategies pursued with concrete outcomes and eventually stated (climate) goals. This causal chain needs to be plausible within a specific context and thus spell out assumptions about the boundary conditions of the environment it is supposed to develop effects in. For instance, a theory of change based on the assumption of perfect data availability within the next five years needs to be explicit about this very assumption. As with theories in science, the more concrete a theory, the better it is as it makes easier falsification, i.e., an assessment of its robustness and thus of the efficacy of finance’s efforts to pursue climate goals.

Currently, the four most commonly employed climate strategies in finance – taking a risk approach, investing in climate solutions, divesting, and engaging with companies – seem to be underpinned by four different theories of change. Yet, these underlying theories are often either not made explicit, blended inconsistently or simply rejected or accepted without interrogating underpinning assumptions. In the following, we review and reflect on these different theories of change, their strengths and weaknesses, and how finance knows or does not know whether they work.

Taking a risk approach

The perhaps most widespread theory of change purports that pricing in so-called transition risk [1]will lead to a gradual shift of capital allocation away from high-emitting assets to those companies and assets that are expected to thrive in a low-carbon economy. Given how familiar and fundamental the concept of risk is to the financial system, this theory of change is intriguing as it can potentially utilise existing organisational structures, risk assessment tools and methods, and perhaps most importantly existing regulatory mandates to further the goal of combating climate change. The TCFD and the work of the NGFS are the most prominent examples of the first step in this theory of change seemingly coming to fruition.

For the risk approach to be plausible and to work, three conditions need to be in place. First, for market prices to adjust to risk signals, these signals need to be perceived as credible. The most prominent driver of transition risk – climate policies – does not always appear credible in most high-emitting developed countries. The current geopolitical situation is being used to justify fossil fuel extraction closer to home, key emission reduction measures are watered down or abandoned due to public resistance against their unjust designs, and self-set climate goals are being missed by the year. Equally, while trends differ across geographies, the risk of consumers rejecting carbon-intensive lifestyles such as the consumption of animal products, fast fashion etc. on a global level seems minor at best given production figures of meatLink opens in a new window or clothesLink opens in a new window. This poses the question of whether transition risk signals are credible enough to significantly affect prices and thus capital allocation.

Second, as Mark CarneyLink opens in a new window remarked in his landmark speech on climate risk in 2015Link opens in a new window, climate change constitutes a tragedy of the horizon with decisions shaping potential climate change mitigation being made in the present and near future while the effects of those decisions will only be felt in the medium- to long-term future. Stock traders are assessed on their P&Ls on, e.g., a monthly basis, asset managers need to justify their performances on annual and quarterly bases, and insurers renew contracts annually. For instance, the fact that oil & gas majors have been amongst the best performing stocks lately may suggest that transition risk is not materialising on these time horizons yet. Do transition risks lie too far out in the future to significantly affect current asset pricing?

Lastly, in order to affect the cost of capital and eventually have an impact on carbon emissions in the real economy, transition risks would need to affect asset prices profoundly, not just marginally. With climate risk being integrated in traditional comprehensive risk assessments, will it outweigh or be muted by other types of risks? Will the effect on capital costs be significant enough to seriously affect the ability of large carbon-intensive companies to continue their operations – companies which often have balance sheets large enough to not having to rely on capital markets?

Currently, research on the degree to which climate-related risk differentials are being reflected in market prices largely comes from academia or public bodies such as the BISLink opens in a new window or the IMFLink opens in a new window and presents a mixed picture of climate risk being only moderately or not at all reflected in market prices. This poses two questions: first, should the financial sector itself, including service providers such as credit rating agencies, start providing better information on the degree to which climate-risk is being priced in? Second, how can we know whether the pre-conditions for the risk approach to work – especially a belief in the credibility of transition risks and a long-term outlook – are currently given in financial markets?

Investing in climate solutions

Often seen as the flipside of downside risk, so-called climate solutions are increasingly being perceived as investment opportunities, i.e., upside risk. Investing in climate solutions such as renewable energy providers, lab-grown meat companies, or home insulation providers directly helps to build a low-carbon economy, thus eventually reaching envisaged climate goals. For this theory of change to be plausible and to work, two related questions need to be answered convincingly: (a) how can we know the significance of a climate solution and, (b) how do we know an investor’s contribution to said solution? For instance, is the manufacturing of electric cars a significant climate solution to replacing internal combustion engines on roads; is it only replacing low-emission vehicles; is it in fact adding to the number of cars on the road without a replacement effect; or is it even stalling a more fundamental shift from individual to shared and public transportation? As to the role of the investor in all of this, is an investor buying shares in this electric car manufacturer contributing at all to the climate solution or only those investors lending directly to the company thus facilitating production? In other words, under what conditions can an asset class-specific investment strategy even credibly claim a contribution? Hence, there needs to be clarity around the mechanisms through which a specific investment in certain asset classes supposedly contributes to the delivery of a given climate solution. Building consensus across financial markets on these kinds of questions seems a necessary pre-condition for this theory of change both to be followed at scale and to be assessed as to its efficacy.

Divestment

Especially civil society groups and social movements have advocated for a strategy that does not want to rely on indirect risk pricing or displacement effects: divestment. Divestment has been practiced for centuries in the context of faith-based investing and for decades in its somewhat more secular version of avoiding ‘sin stocks’ such as tobacco, alcohol, gambling, or specific weapons systems. In the context of climate change, however, divestment is widely rejected as a strategy by large financial institutions. The most prominent argument against divestment is that every share being sold by a climate-conscious investor will simply be bought up by an investor without any climate ambitions, effectively insulating the company in question from shareholder pressure. Hence, shareholder engagement to push companies towards decarbonisation is typically presented as preferable.

Such outright rejection of divestment, however, typically fails to engage with the wider theory of change behind divestment and ignores the possibility of collective action by investors. If all members of the NZAOA, for instance, divested from fossil fuels, affected companies would certainly experience significant pressure. However, given the recent anti-trust concerns surrounding the net zero alliances and any kind of collective effort around climate change, it is not clear how conducive the current conditions are for this theory of change to come to fruition.

A second theory of change behind divestment does not rely so much on a level of collective action that would affect share prices and cost of capital for carbon-intensive companies directly. For instance, in the context of the divestment campaign against the South African Apartheid regime, it has been argued that the effective mechanism was not the direct effect on, e.g., sovereign bond prices and interest rates, but the cultivation of a hostile environment for the regime, and an atmosphere in which it became less and less socially accepted to collaborate and engage with it – whether as a company, a government, or an investor. Here, divestment functions as a symbolic act changing norms and discourse, as outlined in a previous blog post. Divestment in the context of climate change could thus become a social tipping pointLink opens in a new window by playing a role together with other societal actors to nurture anti-fossil fuel normsLink opens in a new window. This approach offers the added advantage of extending the effects beyond companies issuing publicly listed bonds and equity to private and state-owned companies. There is substantial evidence from academic research that divestment campaigns do influence the discourse and norms in particular settings, thereby curbing capital flows to those companies being targeted[2]. For example, Cojoianu et al 2021, using data on 33 countries, find that divestment campaigns reduced capital inflows into fossil fuel companies.

Engagement

Engagement currently is the strategy of choice for most institutional investors and banks to pursue climate goals. The theory of change underpinning this strategy is simple: Ownership of shares or debt obligations come with a certain amount of alleged control or at least with a platform which can be used to convince or help management to decarbonise. Financial institutions are convinced enough of this theory of change to build coalitions around particular engagement campaigns to amplify their voice, and to organise engagement more efficiently, such as CA100+. Collective action therefore seems to be within reach under certain conditions.

While engagement comes with the benefit of not having to restrict one’s investment universe and thus potentially increasing risk in one’s portfolio or missing out on future returns, engagement has a mixed track record. The lack of success of climate-related engagement where it matters most – with oil & gas majors – has prompted a past advocate of engagement – the Church of England Pension Board – to announce divestment from companies such as Shell which remain irresponsive to investors’ engagement demands. This episode illustrates how engagement as the only strategy within a theory of change might render the causal chain leading to climate goals implausible, thus raising questions as to the strategies’ efficacy. The complementary role that divestment could play as an additional strategy within a theory of change illustrates how finance should explicitly combine and connect different strategies coherently within a theory of change, and treat those strategies as different tools in the same toolbox appropriate under different conditions.

Recently, several asset owners and asset managers have voiced a more general concern casting doubt on the robustness of all other theories of change discussed so far: The overall policy and market environment is simply not conducive enough for truly climate-aligned investment. With investors still being legally obliged to generate maximum profits on behalf of their clients and fiduciaries, the fact that not all investment needed to mitigate climate change are good financial investments, and not all high-carbon assets are financially bad investments leaves financial institutions in a dilemma: how can both profit imperatives and climate goals be met? To solve this dilemma, engagement is increasingly being expanded into so-called policy engagement, i.e., lobbying. The theory of change here is for regulators and supervisors to deliver a market design via laws and policies that aligns profitability with climate goals or at least removes barriers to climate-friendly investment. So far, however, there has been a lack of transparency on content, frequency, and effect of climate-related policy engagement by the financial sector posing the question what kind of information would be needed to facilitate an assessment of this theory’s efficacy.

Beyond the difficulty of such assessment, there is a deeper challenge to this theory of change which comes with the openly political stance financial institutions take in advocating for a specific climate-friendly market design. The anti-ESG movement in the US alongside widespread popular backlashes against environmental policies as hurting the working- and middle-class population – including the often-cited gilets jaunes – should be a cautionary tale to a financial sector often seen as synonymous with a wealthy elite which has already received preferential treatment during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 at the cost of workers, mortgage holders, and taxpayers. Hence, for a climate-related policy engagement strategy that openly puts financial institutions into the arena of politics to be sustainable and successful, justice and equity considerations – i.e., a Just Transition – would need to be at its centre. The necessity of public support for a low-carbon transition poses the even more fundamental question for financial institutions of whether, and if so how, their policy engagement can facilitate a democratic process and consensus building. This might require the financial sector to amplify and voice the interests and demands of civil society organisations, social movements, and scientific bodies in its conversation with regulators and public sector representatives. In other words: climate change and the transition is inevitably and fundamentally a political issue, and, albeit uncomfortable, stands need to be made.

Three steps to clarify finance’s theory of change

With open questions surrounding all of the theories of change outlined above, it is not so much a matter of whether any specific theory is right or wrong, but of how financial institutions can know when a specific theory is working or not. We suggest three steps to develop a better understanding of this very question.

- Finance needs to explicitly and transparently construct theories of change, i.e., causal chains connecting strategies with contextual conditions and desired outcomes. Such theories of change can entail multiple strategies as long as they are logically linked and do not undermine each other.

- It needs to be evaluated whether the contextual conditions assumed and causal links proposed seem plausible in a given time and place or whether a theory needs to be adapted.

- Finance should develop assessment systems to gauge the degree to which specific theories of change hold and which strategies develop which desired or undesired effects.

For many years the financial sector has been calling for more and better corporate disclosure as basis for climate-related assessments and subsequent investment decisions. With greater clarity around which theories of change are being employed in which context, more attention could be paid to information needs related to the assessment of a given theory’s and strategy’s efficacy. This may expose new data gaps, such as, the lack of information on displacement or rebound effects associated with climate solutions. It could also lead to the realisation that key information is indeed already available rendering the call for ever more granular and comprehensive disclosure somewhat unnecessary, freeing up resources and attention within both corporates and finance.

More fundamentally, a more explicit discussion of theories of change underpinning different climate strategies could have generative effects potentially broadening the current menu of available theories. For instance, perhaps policy changes are not the only way out of the dilemma of conflicting climate and profit goals. Fiduciary duties are not limited to the principle of prudence but also include the principle of loyalty and thus the possibility for a dialogue with fiduciaries around their actual and not just assumed preferences regarding investment outcomes and strategies.

Independent of the answers found and theories developed, the three steps proposed in this blog need to be taken with the urgency required by a rapidly diminishing remaining carbon budget and continuously increasing climate extremes.

[1] Transition risks are financial risks arising from the transition to a low-carbon economy such as climate-related legislation, shifts in consumer preferences towards more low-carbon products, low-carbon technology innovation disrupting markets etc.

[2] Ding, N., Parwada, J. T., Shen, J. and Zhou, S. (2020). ‘When does a stock boycott work? Evidence from a clinical study of the Sudan divestment campaign’.Link opens in a new window Journal of Business Ethics, 163, 507–27.

Cojoianu, T. F., Ascui, F., Clark, G. L., Hoepner, A. G. F. and Wójcik, D. (2021). ‘Does the fossil fuel divestment movement impact new oil and gas fundraising?’Link opens in a new window. Journal of Economic Geography, 21, 141–64.

Miglietta, F., Di Martino, G. and Fanelli, V. (2022). ‘The environmental policy of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund-Global and investors' reaction over time’Link opens in a new window. Business Strategy and the Environment.

The Net-Zero Alliances: insights from a political theory perspective

In recent years, several net-zero alliances have sprung up in the financial industry. In this blog post, we view these net-zero alliances from a political theory perspective and ask how one might understand the kind of responsibility that financial institutions are taking when joining and participating in such alliances. Drawing on the political theorist Iris Marion Young, we suggest that financial institutions’ responsibility in climate change can be understood in terms of a “political responsibility” that aims to address structural injustices. This perspective entails two key insights for finance professionals and their stakeholders. First, the net-zero alliances can be understood as vehicles to achieve structural change in finance’s own practices and the practices of the economic entities that they finance. Second, to enable structural change, public deliberation that ensures the voices of external stakeholders are heard and taken seriously remains critical.

Joseph Conrad & Katharina Dittrich

A starting intuition

There is an intuition that financial institutions who join net-zero alliances, such as, the NZAOA, NZBA, NZAM or the PAAO, are doing the right thing[a]. It seems right that they take the initiative and join forces with other financial institutions to collectively move their industry toward a net-zero transition. In light of the climate crisis, they are doing something that we might want and expect them to do.

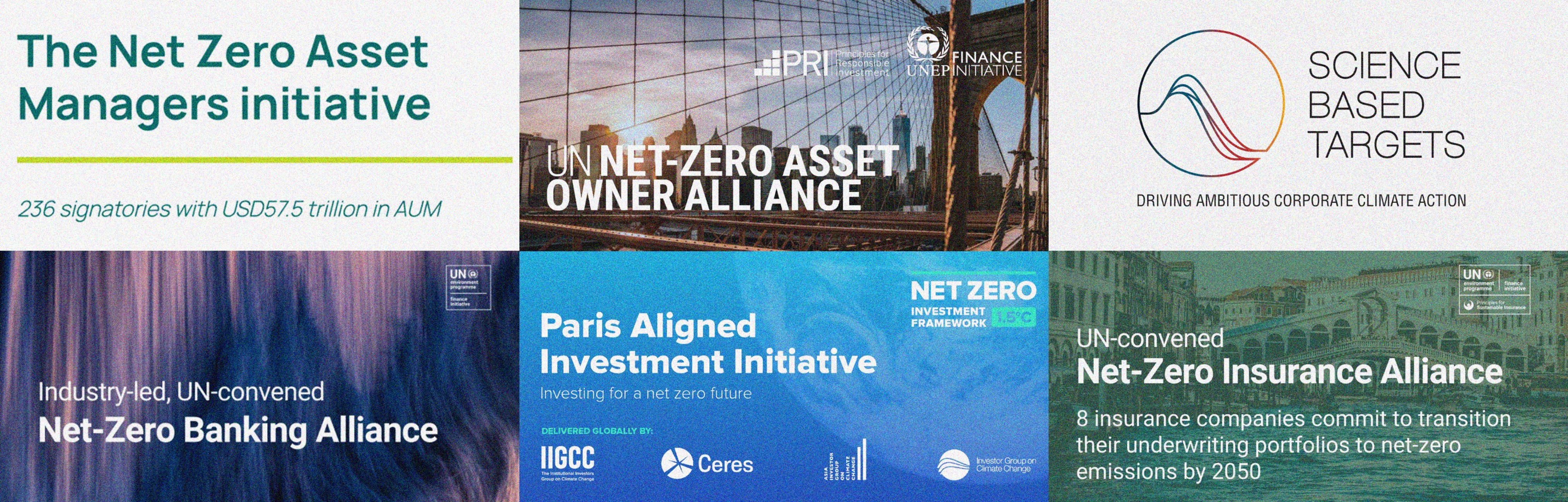

As a brief reminder, the net-zero alliances have two broad objectives. First, the alliances commit financial institutions to setting climate targets in line with 1.5 degrees pathways and reaching net-zero emissions by 2050. Second, they develop industry-wide standards regarding how to set credible ‘science-based’ climate targets. Thereby, they define a minimum level of ambition within the financial industry about what it means to operate in alignment with the 1.5°C Paris Alignment goal. (You can learn more about the various net-zero alliances and initiatives in this blog post.)

Among the various net-zero alliances, the NZAOA, the NZBA, and the NZIA stand out. These three alliances have a particular governance structure. On the one hand, they are industry-led. But on the other hand, they are convened by UNEP FI. The NZAOA, in addition, is advised or supported by civil-society organizations and scientific research institutes, such as, WWF, Global OptimismLink opens in a new window, and PIK. This means that within these three alliances, but especially within the NZAOA, not only private financial interests but public-good oriented voices are present as well.

So, it seems that the net-zero alliances are doing something right, both in terms of their ambition as well as how they are governed. Is there a way to theoretically underpin this intuition? How can we understand the kind of responsibility that financial institutions are taking when joining and participating in a net-zero alliance? And what is it that net-zero alliances aim to achieve?

Iris Marion Young’s political theory: structural injustice and political responsibility

Moving from intuition to theory, we draw on the influential feminist political theorist, Iris Marion Young, and suggest that the activities of financial institutions in the net-zero alliances can be understood in terms of her conception of “political responsibility” in relation to structural injustices. A structural injustice, according to Young, is an injustice that arises not because of the blameworthy actions of a few identifiable actors. Instead, it arises from everyday practices that a vast number of individuals as well as institutions routinely participate in and that are considered normal. Such an injustice is structural because it concerns the social rules, norms, practices, and processes that structure our everyday actions and interactions.[1]

What motivates Young at her time of writing in the early 2000s is the injustice of sweatshop labour in countries such as Indonesia, Bangladesh, and the Philippines.[2] Certainly, we can single out and blame some actors, such as factory owners, for the exploitative and often inhumane working conditions of garment workers. However, this would absolve many other actors from taking up responsibility who are connected to sweatshop labour, too, though perhaps more indirectly. For example, there are the multinational brands that outsource production, high-street outlets who sell cheap fashion items, and millions of consumers who buy them.

Young claims that it makes little sense to blame all these actors for their contributions to sweatshop labour. We cannot hold them morally responsible in the sense that they would have culpably caused something bad to happen and now they need to ‘clean up their own mess’. After all, often their contributions are miniscule, often they contribute without knowledge or intent, and often they lack alternative options. Nevertheless, these actors can be held politically responsible. For Young, political responsibility is a shared, forward-looking responsibility to transform unjust social structures. Her idea is that actors who participate in unjust social practices that are ‘too big’ for them to change on their own should collectivise and organise to achieve structural change.[3]

Climate change as a structural injustice

Now, what can we learn from Young’s political theory in the context of climate change? From her perspective, climate change can be considered a structural injustice to which financial institutions and other economic entities are connected through their business practices.[4] To start with, climate change is caused by the actions of a vast number of individuals and institutions. Often, actors’ contributions in terms of their greenhouse-gas emissions are miniscule, they do not intend climate change to occur, they act in ways that are considered normal, and they lack alternative options.

Further, climate change impacts interact with existing social structures. The ways in which people around the world experience climate change harms depend not only on their geographic location but also on the social-structural position they occupy within global society. For example, it is well known that the global poor and especially women in the Global South are more vulnerable to climate change harms.[5][6]

Finally, climate solutions require structural changes. It is not enough for a few actors to change their individual practices. Rather, we need to enable all social actors to change their practices collectively.

Financial institutions’ political responsibility in climate change

Climate change is a structural injustice to which financial institutions contribute through their investment, lending, and insuring of economic activities that are associated with greenhouse-gas emissions. This includes the financing of fossil-fuel assets and other emissions-intensive activities as well as more broadly the financing and facilitation of any activity that relies on the use of energy, land, materials, or transportation. It thus follows that financial institutions bear political responsibility in climate change, i.e., they have a shared, forward-looking responsibility to collectivise and organise to achieve structural change in social practices.

What do we learn from Young’s perspective? We believe there are two key insights for finance professionals and their stakeholders.

First, the net-zero alliances can be understood as vehicles to achieve structural change in finance’s own practices and the practices of the economic entities that they finance. Of course, the alliances are voluntary initiatives that bring together ‘climate leaders’ and enable them to set net-zero targets. Yet, the alliances’ broader impact could be to change financial practices and thereby move the whole industry to align itself with 1.5 degrees pathways. This would mean that instead of measuring how much capital worldwide is committed to net-zero, the net-zero alliances need to look at how the investment, lending, and insuring practices are changing through their work. One important way to do this would be more conscious work regarding the alliance’s respective theory of change about how net-zero targets will change finance’s own practices, and in turn how these changes accomplish change in the real-economy, rather than just lowering the risk for financial investors or meeting client demand. What are the structural changes in finance’s practices that the alliances can achieve and that will have the greatest impact on the real economy? Both the NZAOA and SBTi-FI explicitly discuss their theory of change in the respective target-setting protocols, but the other net-zero alliances under GFANZ are less explicit about it. Another important avenue is identifying and advocating for policy changes that create the enabling environment for the structural changes the alliances aim to accomplish.

Second, Young’s conception of political responsibility requires public deliberation about who should do what and how. This is because achieving structural change in social practices is never easy.[7] Public deliberation would ensure that the voices of external stakeholders such as UNEP FI, civil society organisations, and scientific research institutions are heard and taken seriously. It would also ensure that those finance professionals working to achieve structural change take sufficient distance from their own practices to see how structural change can be accomplished. The net-zero alliances need to critically reflect on in what ways and to what extent they already allow for public deliberation and what would be measures to improve this. Ideally, the net-zero alliances would engage in a much broader debate about financial institutions’ role in addressing climate change.

[1] Young, I. M. (2011). Responsibility for Justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford & New York.

[2] Young, I. M. (2004). Responsibility and Global Labor Justice. The Journal of Political Philosophy: Volume 12(4), pp. 365-388.

[3] Young, I. M. (2011) Responsibility for Justice. Oxford University Press, Oxford & New York.

[4] Sardo, M. C. (2023). Responsibility for Climate Justice: Political not Moral. European Journal of Political Theory, 22(1), pp. 26-50.

[5] Gardiner, S. M. (2010). A Perfect Moral Storm: Climate Change, Intergenerational Ethics, and the Problem of Corruption. In S. M. Gardiner, S. Caney, D. Jamieson, and H. Shue (Eds.), Climate Ethics: Essential Readings. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

[6] Cripps, E. (2022). What Climate Justice Means and Why We Should Care. Bloomsbury, London.