Geographical Context

By Olivia Law and Becky Latcham-Ford

What is the location? How is it described? Significance?

Childhood in Tehran

At the beginning of the novel, the safety and familiarity of Marji’s home is contrasted with the dangerous political activity on the streets. While Marji yearns to be a part of the action, Satrapi shows that her vision of events is naïve, such as when Marji protests on what turns out to be ‘Black Friday’ (39). During the Iran-Iraq war, Marji’s home is no longer such a safe place. The violence of the outside world invades her own private world, forcing her, her family and neighbours into the basement during air raids. When her neighbour’s apartment block is bombed, the line between the political and personal space is crossed and the danger in Iran is more perceptible than ever to Marji. This potential danger in a place which is supposed to be the safest and most comforting ultimately leads to Marji leaving the country.

the streets. While Marji yearns to be a part of the action, Satrapi shows that her vision of events is naïve, such as when Marji protests on what turns out to be ‘Black Friday’ (39). During the Iran-Iraq war, Marji’s home is no longer such a safe place. The violence of the outside world invades her own private world, forcing her, her family and neighbours into the basement during air raids. When her neighbour’s apartment block is bombed, the line between the political and personal space is crossed and the danger in Iran is more perceptible than ever to Marji. This potential danger in a place which is supposed to be the safest and most comforting ultimately leads to Marji leaving the country.

Marji’s school is the other main place in which she is depicted as a child. However, unlike in her home as a young child, she struggles with being herself in this space. She rebels against the authority of her teachers and the rules of the institution that limit her behaviour and how she dresses. School becomes a limiting space for her and she is continuously reprimanded for her behaviour.

Return to Tehran

When Marji returns to her home in Tehran she has to make the transition from living on her own to living with her parents. Marji struggles with the transition and becomes depressed. Furthermore she has to adjust to an altered Tehran. Tehran physically looks different and Marji is shocked by the changes, such as the ‘sixty-five-foot-high murals presenting martyrs’ (252) around the city. She can no longer walk the streets without thinking of all the atrocities that have taken place there. Her own perception of Tehran changes: all she can see in the city are ‘the victims of the war I had fled’ (253).

While her marital home with Reza should be a shared space, Marji is extremely unhappy in it as she feels she is not truly herself when she is there. They marry so that they can live together and so their marital home is the result of the pressures of wider society. Marji is not comfortable with who she is in her relationship with Reza and so is uncomfortable in the space that represents it. As the tension and fragmentation in their relationship grows, so does the space between them. Marji and Reza are shown in separate beds with a large gap in between (321). The physical space between them represents their broken relationship and the psychological distance between the two.

Austria

Although Marji leaves Tehran in the hope to gain independence it is clear that she is still unable to gain control over her surroundings. In the boarding house with nuns Marji is once again denied complete freedom and even in her own apartment it is not wholly her own space as she is controlled by the landlady. This lack of control is illustrated by Marji’s time living on the streets. This unfixed space in which she belongs perhaps represents her torn identity between the East and West and is further illustrated by her time in airports that are a place of no fixed space or identity.

France

When Marji finally leaves Tehran at the end of the graphic novel she is sent to France. The reader is unaware of her new space in France but is instead aware of her motives to leave. Marji is in the hope of living in a less restrictive society and thus Marji chooses a new location based on changing the space in which she is able to interact in. However it is evident that Satrapi, as the author, had to chose between the two spaces (Tehran and France), as her books are still unable to be printed in Tehran.

Satrapi writes the book in France and therefore this distance provides her with creative space in France where she can reflect on her experience. This is contrasted to the art school that she attended in Tehran where creativity was completely restricted, as they had to draw the human body from models with clothes on.

How do characters physically interact with their space? Empowering or constricting space?

When the civilians protest again the government in the streets, as a mass, they dominate a large area of space in the street. However these protesters are shot down by the regime through brute force thus portraying that in Persepolis space in the city is a metaphor for power. Both the regime and opposing civilians fight for this space in order to obtain power. This battle for power is further portrayed in the renaming of streets after martyrs as the regime’s ideology is imposed on public space. This links to the Iran-Iraq war depicted in the novel. Iraq bombs Tehran in the hope that through bombing civilian space they will gain the upper hand in war.

Marji herself is not just physically but mentally affected by the different spaces that she is in. When Marji returns to Tehran she is depressed. However through the activity of aerobics Marji is able to re-connect with her body and relieve herself from depression. This is perhaps due to her freedom to wear what she wants to in the aerobics studio thus she is able to reconnect with her own personal space rather than in the politically defined streets.

Do characters uphold or subvert official/expected use of space in Iran?

Due to the strict regime there are numerous rules regarding what people can and cannot do in public space and thus personal space is incredibly important. Personal space therefore becomes a means by which people can subvert the rules of authority. This is illustrated by the private parties that Marji’s family, and like-minded friends, host in their home. When they have their parties, they even cover their windows in fear of being discovered—boundaries between the outside and personal space have to be reinforced. Similarly the Regime’s ideological beliefs impinge on her own personal space by forcing her to wear the veil. Marji rebels in her own personal space through wearing Western accessories and clothing whilst still wearing the veil, despite being threatened by the authority.

How do characters represent space? How do represented spaces compare to the ‘real’ space in world?

Space is represented on multiple levels; space seen through the eyes of Satrapi the author, Marji the narrator andvisual narration. It is apparent however that whilst Satrapi is portraying the ‘real’ space in Iran it is an extremely simplified portrayal of the situation in Iranian society both through the minimalistic pictorial space and in the space seen through the eyes of Marji. While Marji has a child’s view of space, the simplicity of her representations of space (such as the streets during the many violent protests) still starkly communicate the violence and oppression of the regime.

Space in the visual narrative

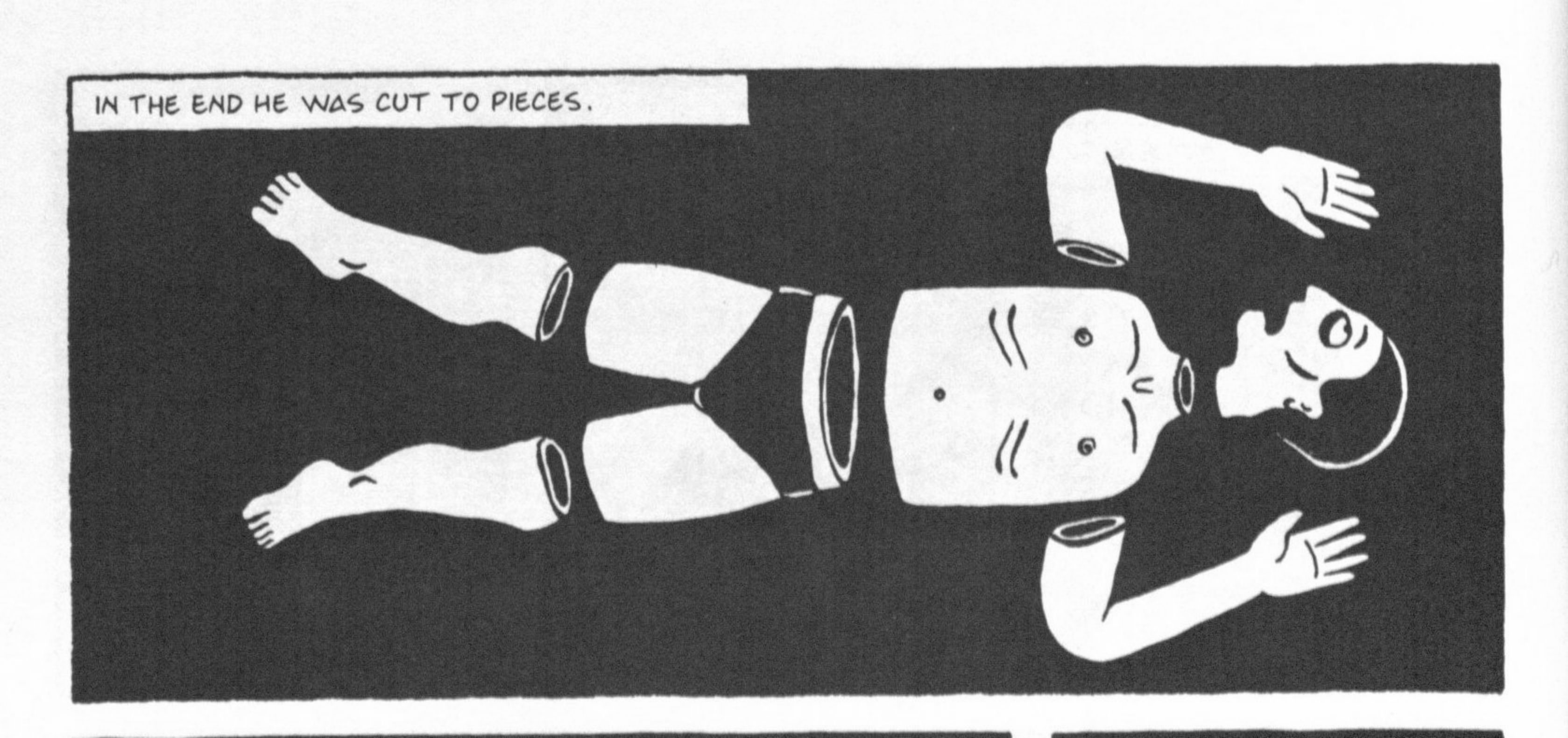

Persepolis is a graphic novel and so space is represented both textually and visually. However the main space of the novel is dominated by the visual. This visual space perhaps allows Satrapi to convey her experience more effectively than solely with words, as she has said: ‘I cannot take the idea of a man cut into pieces and just write it. It would not be anything but cynical. That’s why I drew it.’ (Bahrampour 2003, E1).

Satrapi offers only monochromatic black and white drawings and thus there is a disjuncture between the minimalism of the drawings and the trauma they depict. Black backgrounds of the panels are often associated with trauma and thus Marji’s psychological state of distress is depicted by the confining black box.

The opening frame shows Marji set apart from the other veiled children, as she is alone in her own frame. This is indicative of the central theme of the novel – one of loneliness whilst searching for a fixed identity- and thus Marji often finds herself set apart in her own personal space. This sense of alienation and psychological fragmentation is explored by Hillary Chute who maintains that, ‘Satrapi uses spacing within the pictorial frame as the disruption of her own characterological presence. We do in fact, clearly, “see” her – just not all of her- but her self-presentation as fragmented, cut, disembodied, and divided between frames indicates the psychological condition suggested by the chapters title, “The Veil”. ‘(96) The opening lines of the graphic novel consist of the words, ‘you do not see me’ (3) and yet she is depicted visually in the opening frame. This creates immediate space between the visual and the written narration.

Satrapi shifts from panels about her personal experiences as a girl to those about the political context of the time. These transitions shows how closely interwoven the political and the personal are apparent in her life.

In the graphics portraying the dead, executed by the regime, there is very little visual space between the people, notably images on pages 39 and 258, therefore perhaps portraying the solidarity between the dead but also the repressive and claustrophobic nature of Iranian society at the time.

Works Cited

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis. New York: Pantheon, 2003. Print.

Bahrampour, Tara. 2003. "Tempering Rage by Drawing Comics," New York Times, May 21.

Images from: http://satrapism.wordpress.com/artword-and-the-visual-persepolis/