1774 Madhouses Act

Jennifer Crane

Whereas many great and dangerous abuses arose from the present state of houses kept for the reception of lunatics, for want of regulations with respect to the persons keeping such houses, the admission of patients into them and the visitation by proper persons of the said houses and patients: and whereas the law, as it now stands, is insufficient for preventing or discovering such abuses.

(The Act for Regulating Private Madhouses, 1774, Preamble.)

Whilst private asylums began operating in the early 1600s, the status and powers of madhouse keepers was undefined in law until 1774. Hence, for much of the eighteenth century there was no State regulation, or responsibility, for the daily happenings or day-to-day management of private asylums. Consequently, numerous private madhouses became subject to public scandals, accused of horrific abuses, malpractices, and patient mistreatment. Of particular public concern was the issue of ‘wrongful confinement’. Indeed, a Parliamentary committee investigating in 1763, uncovered a disturbingly high number of sane people stowed away within private asylums for the financial or social benefit of their 'friends' and relatives. Notable cases included a wife imprisoned by her husband for lacking passion and acting 'indifferently' within the bedroom, and two young girls locked up to halt love affairs their parents did not approve of.

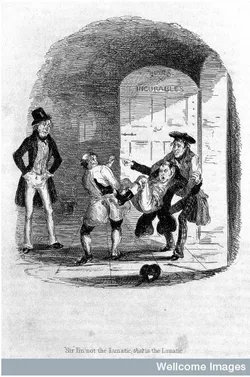

Cartoon depicting wrongful confinement, from James Grant, Sketches in London (London, 1838)

These concerns led to Parliamentary action, and in 1773 a Bill was introduced into the Commons by Parliamentarian Thomas Townshend, who claimed to have heard 'facts . . . which would awaken the compassion of the most callous heart'. The resultant 1774 Act for Regulating Private Madhouses aimed to better restrict the private trade in lunacy through three key provisions. Firstly, the Act set limits on the number of patients who could be admitted into madhouses. Secondly, the Act created licenses and regular inspections for madhouse proprietors. Inspections within London where to be carried out by five Commissioners newly appointed to the Royal College of Physicians. In the provinces, inspections would be conducted by Justices of the Peace. Finally, the Act made it necessary to obtain medical certification for the incarceration of lunatics.

Whilst this legislation contained theoretically beneficial provisions, its practical impact was limited, and the Act has been labelled 'toothless' by historian of medicine Roy Porter. Disturbingly, the Parliamentary Committee on Madhouses in England of 1815 found that obtaining a license represented little more than a formality. Indeed, there is no evidence that a licence was ever refused. As such, the Act can be interpreted as licensing and permitting the abuses of the status quo, rather than eradicating them.

The 1815 Parliamentary Committee also criticised the superficial nature of most inspections. Inspectors would not spend much time within the asylums or properly scrutinise their conditions. The physician William Pargeter noted that many madhouse keepers, when inspections were due, would move 'sane patients out of the way; or if that cannot be done, give them large doses of stupefying liquor, or narcotic draughts in order to conceal wrongfully confined patients from inspectors.

A final failing of this Act was that it did not require that medical certification was gained in order to incarcerate pauper patients. As pauper patients constituted the majority of private asylums' populations by the late eighteenth century, this meant that wrongful confinements, were by no means, fully prevented by this Act.

Despite these flaws, the 1774 Act established an initial framework for improving the regulation of private asylums, and did appear to tackle wrongful confinements to some degree by enshrining in legislation the principles of licensing, visitation, and inspection. These principles were developed in nineteenth-century legislation, including the 1828 Madhouses Act and the 1845 Lunatics Acts. Hence, the 1774 Act did not end the evils of private madhouses. But it did put them on the agenda of public concern and facilitate future change.

Further Reading:

• Charlotte MacKenzie, Psychiatry for the Rich: A History of Ticehurst Private Asylum (London: Routledge, 1992).

• William Ll. Parry-Jones, The Trade In Lunacy: A Study of Private Madhouses in England in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972).

• Kathleen Jones, Lunacy, Law, and Conscience, 1744-1845: The Social History of the Care of the Insane (London: Routledge, 1955).