Chinese Ceramics & the Early Modern World

1. Introduction

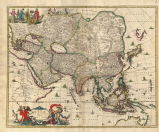

Between 1300 and 1800, porcelain objects manufactured at southern Chinese kilns were some of the most universally desired products in the world. From humble Cambodian traders and Japanese monks to the shahs of Iran and the princesses of Europe, the wide dissemination of Chinese porcelain testifies to cross-cultural encounters on a truly global scale. Both functional and collectable, porcelain objects were also the bearers of cultural knowledge that could be interpreted or absorbed in different ways, and Chinese imports informed, transformed or displaced many of the indigenous ceramic traditions they encountered. This exhibition traces the remarkable journeys of Chinese porcelain to four regions – Japan, Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Europe – during the early modern period.

The popularity of these refined northern ceramics continued for centuries to come, but new styles began to be produced at southern kilns during the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1279-1368). The shift of ceramic industries to southern China was in part a response to invasion by the non-Chinese tribes who had been pressing at Song China’s northern borders. In 1127 those tribes seized the capital (modern Kaifeng) and forced the Song emperor to flee south, where he established Hangzhou as the capital of what became known as the Southern Song (1127-1279). By the time the conquering Mongols under Kublai Khan (1215-1294) established Dadu (modern Beijing) as the capital of the new Yuan dynasty, southern China had become a thriving centre of commerce and culture.

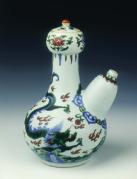

The Mongol khans ruled over Chinese territory much as the Song emperors had done before them, but were far more ready to embrace trade and commerce than their predecessors had been. Throngs of merchants from Central Asia and Iran, from India and Sri Lanka, and from kingdoms on Java and Sumatra arrived in the trading and manufacturing centres of Yuan China, bringing with them the demands of far-flung consumers. Their demands, combined with changes in the composition of the clays and glazes available for the manufacture of ceramics, led to the appearance of the first porcelains in what would become the foremost site of southern ceramics production: Jingdezhen. It was here, also, that potters first experimented successfully with large-scale production of blue decorations on white porcelain bodies. The Chinese potters continued to export a variety of wares to multiple locations—green and red enamelled Zhangzhou (Swatow) wares from Fujian to Southeast Asia, brown- and black-glazed tea bowls and storage jars to Japan, fine white statuettes from Dehua to Europe, and greenwares (celadons) to the Middle East—but blue-and-white from Jingdezhen came to be regarded by many as the epitome of Chinese porcelain. In fact, it came to be seen as ‘China’.

Once the Han Chinese regained control over what had become Mongol territory and established the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the emperor and his Confucian advisers sought to restrict the activities of foreign merchants. The Ming emperors tried to reinforce the agricultural foundations of the empire, while also attempting to limit trade and bring sites of craft manufacture under tighter court control. Fine porcelains were produced in Jingdezhen's imperial workshops for the exclusive use of the ever-expanding Ming imperial household, and court officials were appointed to make a selection of the finest wares as tribute for the emperor. Wares that had the aura of imperial exclusivity were in demand both within and beyond the Chinese empire, and private kilns in Jingdezhen benefited from these expanding markets.

During the Qing (1644-1911), the final dynasty in Chinese history, established once again by non-Chinese invaders of nomadic Jurchen background, the emperors continued to pursue a policy of sponsorship and control at the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen. They made increasingly-complex demands in terms of colours and designs, even insisting on the introduction of styles of decoration known only from foreign imports. Enamelled wares, produced in Qing imperial workshops with the help of Jesuit missionaries who had introduced these items from France and Germany, were one product of this intercultural collaboration.

The objects and images in this exhibition demonstrate that Chinese ceramics were a prominent feature of the early modern world. Exporting to every continent of the known world, Chinese potters responded to the varied desires of their distant consumers, while their ceramics acquired new meanings and uses within their new contexts. These pieces belong to a world that was truly global in outlook.