Research

Shaped on Stone: Lithography and the Foundations of the Modern World

This project seeks to show how the invention of a radical mass media technology shaped the world we live in today.

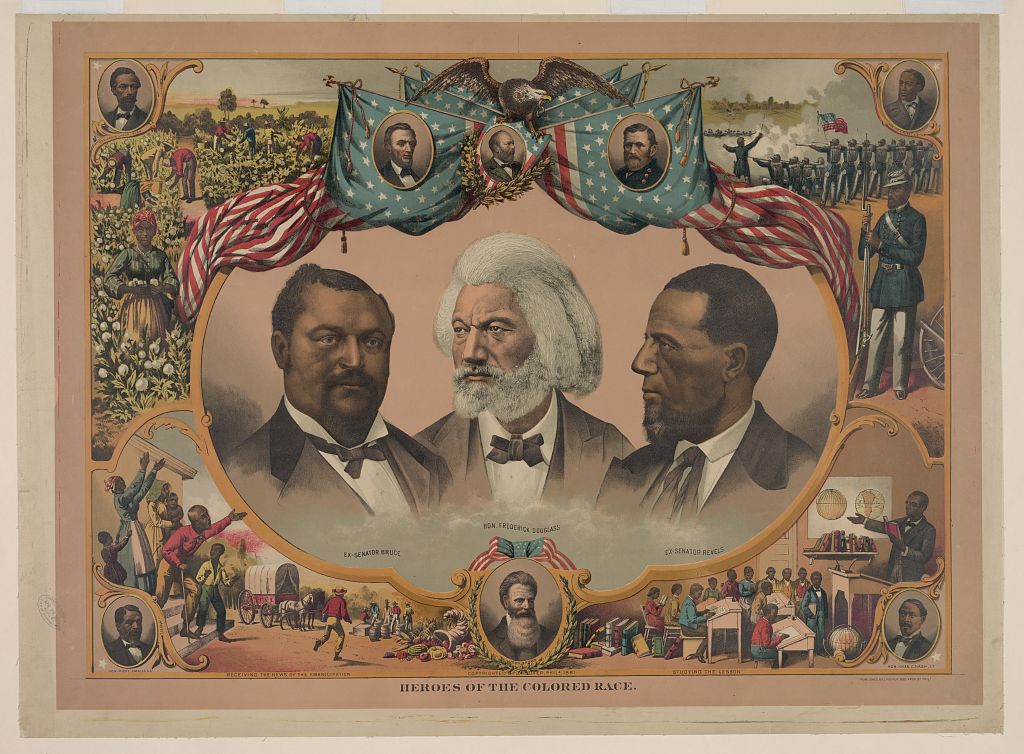

Heroes of the Colored Race, published by J. Hoover, Philadelphia, 1881, chromolithograph.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In the first decades of the nineteenth century, a new medium for mass visual communication spread rapidly across the globe. Termed lithography for its ability to multiply marks made directly onto stone, by 1830 the technology had spread from Bavaria—where it was invented in 1796—to the extremities of Europe, Asia, and the Americas. Unlike earlier print technologies, lithography did not require specialist engravers or significant initial investments to purchase type, both of which had largely confined presses to the metropolis. Relatively cheap and technically easy to produce, lithography instead decentralised print production and catalysed new visual worlds in territories formerly lacking public visual cultures.

This dramatic revolution in global mass media has never been connected to the transformative ‘birth of the modern world’ in the long nineteenth century. The few studies that directly address lithography remain concerned with its technical aspects, its position in the repertoire of satirical artists, or its transformation into a fine art medium, particularly in France. Yet lithography’s financial and technical accessibility made it an important driver of global historical change, instrumental in shaping three of the defining features of the modern world: the rise of the national state; the flowering of Liberalism and working-class dissent; and the increased conflict between religion and secular society. It became the medium of choice for revolutionaries creating visual propaganda during the violent insurrections that rippled across Europe in 1830 and 1848, and it allowed Romantic Nationalists to picture the unification of nations like Italy and Germany. The medium’s financial and technical ease of production saw it dominate the cultural spheres of Europe’s colonial peripheries, where new ideas variously justified or contested imperial rule, while the novel artistic formats it afforded—like the lithographic scrapbook, the illustrated periodical, or the magazine—defined the middle-class ethoses of societies reshaped by the period’s sweeping economic liberalisation. Using case studies taken from Europe, North America, and Asia, my project will be the first to map this global influence, emphasising how a focus on lithography’s revolutionary impact on mass media challenges conventional interpretations of modern history.

Thinking about artistic technology as a driver of global historical change allows my project to bridge the gulf currently separating ‘social art history’ from a more traditional study of artistic materials and techniques. By presenting lithographs not as illustrations of historical processes, or even as agents in the dissemination of political ideas, but as products of a technological development that in itself constituted a political force, I will seek to demonstrate how one of the most fundamental and orthodox aspects of the art-historical discipline might be reconfigured to explore the history of globalisation. Indeed, I believe that writing rigorous accounts of the ways visual technologies have shaped global history is essential if we are to better frame and contextualise our present understanding of the significant political and social turbulence caused by the explosion of new, highly visual mass media. As ‘all that was solid melts into air’, it is increasingly relevant to understand how the modern world was shaped on stone.