Susan Haedicke

May 1968, the Situationists, and the

Development of French Street Arts (France)

Linked to

Performance/Spectacle and Politics (the New Left)

1.1 Susan’s Narrative Begins Here:

Performances have taken over the streets and squares of European cities for centuries and shifted the focus of city dwellers from ordinary day-to-day activities to special events of religious celebration, entertainment, or displays of power through art. These outdoor events transformed the function of the public space in which they took place and rewrote the relationship between the audience, the performer, and the location. The long and vivid history of outdoor performance clearly contributed to what is called street arts today, but contemporary street theatre, especially in France, is not simply a continuation, an elaboration, or a modernization of the traditions of the past. Although adapting centuries-old techniques, the current form of street arts stepped onto the urban stage in the 1960s and 1970s in response to the same anti-establishment impulses and seeds of rebellion that initiated social unrest and led to the vivid, and often violent, demonstrations and riots around the world in 1968.

To understand this shift to performance “outside the walls” that developed into today’s street theatre, it is important to have a sense of the context in which it began to flourish. For political scientist Sheldon Wolin, the 1960s began as a “quest to expand the meaning and practice of democracy” and came to represent a decade in which populations became politicized. In “The Destructive Sixties and Postmodern Conservatism,” from Reassessing the Sixties: Debating the Political and Cultural Legacy, edited by Stephen Macedo, he writes: “The Sixties converted democracy from a rhetorical to a working proposition, not just about equal rights but about new models of action and access to power in workplaces, schools, neighbourhoods, and local communities.” The summative year of 1968 was, in the words of Mark Kurlansky, a popular history writer, “the year that rocked the world”: global unrest representing a world-wide discontent with the cultural, economic and political status quo; a rejection of authority, Western imperialism, dictatorships, and rampant consumerism; and a longing for freedom, justice, and self-determination.

1.2 While demonstrations, marches, and grassroots activism occurred in cities around the world, the events of May 1968 in France were probably the most dramatic and contagious. Only in France were the student protesters joined by ten million workers nationwide who went on strike with similar, although less ideological, demands. There is no question that the May ’68 student-worker revolt challenged the status quo in French society profoundly affecting its institutions, traditions and beliefs.

BBC Radio 4 offered a series of four programs, “1968: The Year of Revolutions,” hosted by Sir John Tusa, discussing the impact of the events of this year of global crisis in London, Paris, Prague, and Chicago.

Programme #2, broadcast on 29 April 2008, focused on Paris.

Ingrid Gilcher-Hotley’s “May 1968 in France: The Rise and Fall of a New Social Movement” from Fink, Gassert, and Junker, 1968: The World Transformed offers an analysis of the events as a “ new social movement” or a mobilization of a group of people over a sustained period of time who seek to affect social change through protests and demonstrations. She argues that this movement opposed the “total structure of society” and was guided by the ideas of the New Left, one of which insisted “that changes in the cultural sphere must precede social and political transformation.”

1.3 The ideas and writings of the Situationists, a group of thinkers and activists, whose most famous name is Guy Debord, gave voice to many of the anti-establishment leanings and had a strong impact on the May 1968 events. The Situationists sought to develop an avant-garde that would initiate a socio-cultural revolution overthrowing the mainstream ideas and practices relating to art, history, politics, urbanism, and everyday life. Key among their concerns was the growing alienation and loss of individual agency in all aspects of contemporary life from production to daily activities. Central to Debord’s ideas (as well as to the missions of many street artists although not as clearly articulated) is a condemnation of what he labelled the “ society of spectacle:” a passive observation and contemplation of images of life that have replaced direct, lived experience so that images have become the new reality, and reality is reduced to images. He warns that the false freedom of free market consumerism in which consumers have the freedom of choice to buy whatever they want from a pre-selected group of items in the shops should not be confused with the freedom of citizens to participate in dialogue and debate about governance in a democracy. To counteract this passivity, the Situationists, in what today seem idealistically utopian goals, suggested an approach that blurred distinctions between art and life in order to stimulate an abrupt awareness of lived experience: the construction of situations that both increased awareness and promoted social transformation.

An excerpt from Debord, “Report on the Construction of Situations” explains early notions of this approach.

1.4 In October following the May 1968 student/worker uprising that nearly toppled the government in France, Michel de Certeau wrote The Capture of Speech, in which he tries to make sense of the events of a few months earlier and assess their impact in the cultural sphere. He calls the crisis a “symbolic revolution… because it signifies more than it effectuates…. From the beginning to the end, speech is what played the decisive role.” He explains quite passionately:

Last May, speech was taken the way, in 1789, the Bastille was taken. The stronghold that was assailed is a knowledge held by the dispensers of culture, a knowledge meant to integrate or enclose student workers and wage earners in a system of assigned duties. From the taking of the Bastille to the taking of the Sorbonne, between these two symbols, an essential difference characterizes the event of May 13, 1968: today it is imprisoned speech that was freed…. Something happened to us. Something began to stir in us. Emerging from who knows where, suddenly filling the streets and the factories, circulating among us, becoming ours but no longer being the muffled noise of our solitude, voices that had never been heard began to change us.

De Certeau argued that while the political regime withstood the assault of May 1968, the “protests created a network of symbols by taking the signs of a society in order to invert their meaning.” They created what de Certeau calls symbolic sites where seemingly impossible images or events “modified the tacitly ‘ accepted’ code that separates the possible from the impossible, the licit from the illicit.” The dominant discourses—political, social, and aesthetic—were thus transformed.

1.5 The linking of aesthetics and politics so evident in the writings of the Situationists and de Certeau was quite visible in the actual street demonstrations as well. Jean-Jacques Lebel who participated in the student protests describes how performance was used on the streets to create “ situations” in the service of revolutionary action in “Political Street Theatre, Paris,” originally published in TDR in 1969 and reprinted in Jan Cohen-Cruz, Radical Street Performance: An International Anthology.

1.6 It was not a large step from the agit-prop theatrical activities described by Lebel to the more professional street theatre that began to flourish in France in the 1970s. Pioneering French street theatre companies abandoned traditional theatre buildings for the freedom and populist appeal of the street, offered their shows to the public for free, and insisted on a revolutionary aesthetic of innovation, provocation, and overthrow of norms. These radical French artists launched artistic interventions into the actual life of the city and thereby affected the public’s understanding of social life by challenging the demarcation between the fiction of the theatre and reality of the street. Their productions created symbolic sites that turned aesthetic expectations and socio-political assumptions upside down when the performers unexpectedly appeared on the streets. The artists took the art to the people and sought to create public memories of familiar urban places transformed by the interventions. They thus offered an alternative social experience based in performativity.

While theatre companies throughout Europe played with a range of outdoor forms from busking to large-scale site-specific productions, street theatre developed and diversified more in France than elsewhere in the three decades after 1968. One of the reasons that an ever increasing number of French theatre companies chose to work in the streets in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s when pioneering militant companies elsewhere in Europe and in the United States folded or moved indoors (with a few notable exceptions) was the existence of favourable cultural policies, claims Floriane Gaber (who has documented street theatre for over two decades) in How It All Started: Street Arts in the Context of the 1970s. Key policies that created a nurturing climate for French street theatre companies were the decentralization of the arts and the encouragement of “people’s theatre.” Both policies sought to engage new audiences—what was called the “non-public.” The street artists, in a much more extreme gesture than the state policy of democratization of culture, took art to the people in order to change their perceptions, not only of art, but of the world in which they lived. They chose to perform outside cultural institutions and linked their performances to actual everyday sites. These early street productions, creating what de Certeau had called “symbolic sites,” turned aesthetic expectations and socio-political assumptions upside down when theatrical moments unexpectedly appeared on the streets. As Gaber claims, they strove to engage people involved in their daily activities by superimposing art on life, and they idealistically sought “to make the populations understand the necessity of theatre as a tool for social transformation.”

1.7 While videos of the early shows do not exist, there are examples from the late 1980s on that illustrate the populist and utopian aesthetics of street theatre and its attempts to engage with key social issues performatively. An important early show that theatricalized the street protests and “ taking back the streets” was Générik Vapeur’s Bivouac.

A short clip of one of the early performances is available on the HorsLesMurs website (street theatre and circus archive in Paris).

To see a video clip of the performance:

In the keyword box, type in “generik”, click the box next to video, then click on “search.” You will see a list of performances. Go to Générik Vapeur’s Bivouac from 1988 (3:21 minutes). Just click on the icon of the DVD on the right. There are video clips from later performances as well.

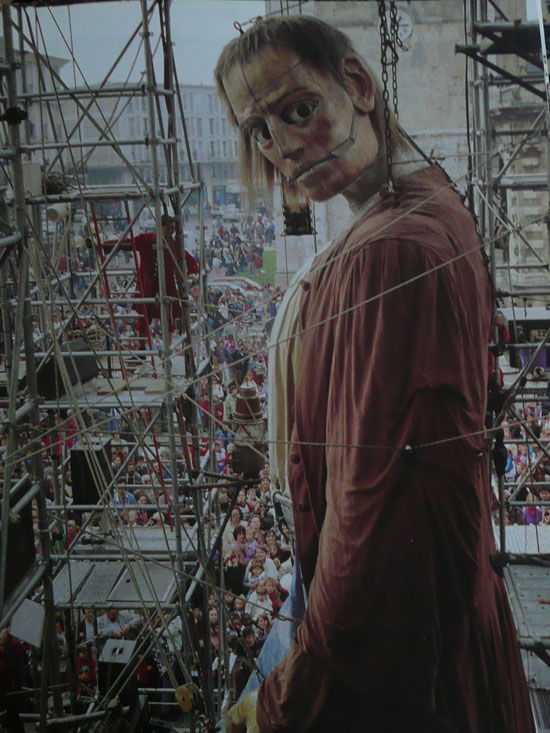

1.8 In 1993, one of the most famous French street theatre companies, Royal de Luxe, created Le Géant Tombé du Ciel. The performance, lasting several days and nights, offers audiences the opportunity to live with a foreigner in their midst—a giant marionette, more than ten meters tall, attached to a scaffolding (his “cage”) and manipulated by approximately twenty men dressed in long red coats. One morning, Léonard, the giant, is found tied, Gulliver-like, to the ground in front of the church. The audience is clearly cast as the Lilliputians. During his stay in the city, Léonard’s routine activities of eating, sleeping, washing, and even relieving himself, openly performed on such a grand scale, magnify the plight of the “outsider” forced to “live” in public, and the visibility of his intimate acts blurs the distinction between public and private space. His enormous size magnifies his solitude as he is stared and pointed at like a freak in the circus, and his promenade through the city signifies a charged confrontation between “us” and “them,” between insider and outsider. He can never really “fit in” with a crowd that is so different and that welcomes him by making him a fairground puppet. And yet while Léonard forces the audience to recognize an unforgiving and intolerant world, he also offers the hope of a utopian dream of unification across difference as he and the huge crowds that follow him and come to love him rediscover the spatial and temporal urban landscape with the wonder of a child.

Video on DVD.

1.9 Les Squames, created by Compagnie Kumulus, is a show that pretends to be an exhibition of a “newly discovered tribe of creatures—part-human, part-monkey” placed in a large cage set up in a public space. The show was originally created in the late 1980s, several years before Guillermo Gomez-Peña and Coco Fusco’s Two Undiscovered Amerindians Visit, and it has been performed sporadically since then. The cast consists of actors playing both the Squames and the security guards who give an “authenticity” to the exhibition to many gullible spectators. When I saw an unannounced performance in front of Gare Montarnasse in Paris in 2007, I was amazed at how many believed it was real. One woman was furious that creatures so human were caged and exhibited, and she railed against the guards and the other spectators for over fifteen minutes. None of the actors—g uards or Squames—broke character. The guards tried to calm her, but when they recognized the seriousness of her fury, they just tried to keep her away from the cage saying she was agitating the Squames. The Squames reacted by cuddling close to one another, rocking back and forth, or howling.

To see a video clip of the performance:

In the keyword box, type in “kumulus”, click the box next to video, then click on “search.” You will see a list of performances. Go to Compagnie Kumulus’ Les Squames: ISTF 1990 (5:49 minutes). The other video of Les Squames takes place a year earlier in Chalon-sur-Saône (7:49 minutes). It shows more the exhibition of the creatures in the cage. Just click on the icon of the DVD on the right.

1.10 The walk-about characters in Ilotopie’s Les Gens en Couleur, first created in 1989, are simple interventions into public space with more significant consequences. As they walk the city streets unannounced with their almost naked bodies painted in thick, shiny colours in shades of reds, blues, greens, yellows, oranges, and purples, they overturn notions of invisibility and simultaneously hint at a sense of danger of hyper-visibility—the double-edged sword of otherness. Each brightly coloured body seems to recognize the hazards of standing out from the crowd, of not blending in, and each is instinctively drawn to objects of the same colour. Deep blue bodies closely follow police in blue uniforms; red bodies wrap themselves around red letter boxes; orange bodies snuggle up to highway workers in bright orange vests or brave the traffic to sit next to orange cones; green bodies find their community among plants and grass and so seek out the parks, gardens, or any other green space in the city, even a window box; and purple bodies often wander dejectedly in search of likeness. Les Gens en Couleur plays with issues of difference and migration as it forcefully casts the city inhabitants in the role of insiders who must accept, reject, or pretend not to notice the outsiders. This simple, cartoon-like intervention powerfully troubles discourses of assimilation as it reveals the pathos of unsuccessful attempts at fitting into the dominant society and suggests the potential problems of segregated communities not only through its bright, but monochromatic groupings, but also through isolation as the reds cannot find a place in the world of the blues or yellows. The politicized performance does not let the spectators off the hook as it demands some sort of audience engagement.

In the keyword box, type in “ilotopie”, click the box next to video, then click on “search.” Go to page 2, and you will see a list of performances. Go to Ilotopie’s Les Gens en Couleur in Buenos Aires in 2006 (10:22 minutes). Just click on the icon of the DVD on the right. (It is not necessary to watch the whole clip to get a sense of the performance.)

1.11 The final example is from a 2008 performance by a contemporary street dance company, Jeanne Simone. Le Goudron n’est pas meuble begins invisibly with everyday activities as, one-by-one, the six performers enter a public space and read a newspaper, smoke, drink a coffee, or lean against a tree. Their studied performance of ordinary activities slowly begins to map the geographic site and its expected spatial practices. The actors perform unannounced, so most of the audience is not expecting to see a show. This unsuspecting public is a crucial element in the performance’s transformation and subversion of the public space from a ‘non-place’ or busy commercial space into a space that encourages human connection grounded in the senses. The space is no longer a transit point, but a participatory performance site as the performers use stylized and choreographed movements to slow down and play with the people going about their daily activities. In this performance space, it is very hard for the public to remain passive spectators since they are drawn into the action as their spectatorial role is unexpectedly transformed into unanticipated acting. The performers stop cars and lorries to climb on them, get into them, decorate them, or dance to music blaring from the radio. They lie down in the street, thus forcing traffic to slow down or put police tape across the entrances to the metro that people must break through or duck under as the escalator carries them to the street level. At one performance I saw, an actor stopped traffic at a busy intersection during rush hour to help a man, leaning on a cane and carrying a mesh bag with vegetables and a baguette, cross the street. The man was a member of the public just doing his shopping, not coming to see a show. Just before the two reached the other side, they turned around and walked back. The shopper had become performer. As the actor and the man, now grinning playfully, began their fourth trip across the street, the watching public joined them. Traffic was snarled for several minutes.

A video clip (12:11 minutes) of Le Goudron n’est pas meuble, performed in Aurillac in August 2008, reveals the start of the show as the actors and their actions blend into the surroundings at first, and it continues as the performers gradually exaggerate ordinary activities to signal performance. (It is not necessary to watch the whole clip to get a sense of the performance.)

1.12 Longtime photographer and chronicler of street theatre, Christophe Renaud de Lage, asserted:

To break the established rapport between stage and auditorium, to leave the beaten path created by institutions, to transform the rapport with the public, to rediscover a taste for risk and innovation, to invent new modes of production, to refuse the tyranny of money and its submission to mass appeal, to imagine other ways of living, to look for new connections with objects, things, and people, to replace the focus on ‘me’ with one on the collective, all that, yes, is really revolutionary, it is true that in order to change life, we must begin by transforming, each at his own pace, our rapport with the world.

Underlying this passionate claim are the ideas and goals of those involved in the 1968 riots: a rejection of the status quo with its hierarchies, capitalism, and consumerism and a quest for justice, equality, free speech, and citizen control over one’s own world—democratic ideals.