Teaching Mathematics in South Africa

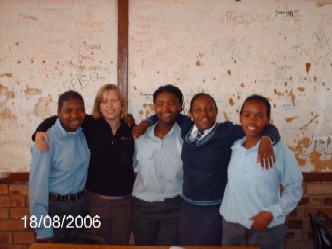

Corrinne Mackintosh, a third year mathematics student, took part in the Student Associate Scheme in South Africa.

Why is teaching important to you?

Teaching has always been a job I thought I would enjoy and be well suited to, and spending time in the classroom and getting some teaching experience on the SAS scheme in the UK confirmed that this was a career path I would love to follow. Teaching is an opportunity to give something back to society, to make a valuable contribution to shaping young people’s lives and help equip them with skills for life. Especially in the field of mathematics education, I feel boosting pupil’s self-confidence and passion for the subject is very important, which as a teacher you are in an ideal position to do. I enjoy working with young people as their energy and enthusiasm is very stimulating, and I love being able to make a difference in pupils’ lives, be it big or small.

How did the opportunity to teach in South Africa arise?

Pam Griffiths, key organiser of the SAS scheme mentioned during one of the course meetings that she was working with Professor Colin Sparrow (Chair of the Warwick Mathematics Institute) to organise a trip to South Africa, and she was looking for interested students. Having decided on teaching as a career path, and being a keen traveller, I jumped at the chance, and offered to lend a hand with the pre-trip organisation, along with two other students, Geoff and Claire. We were lucky enough to strike an excellent liaison with The University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg who helped organise school placements, transport and accommodation for us on the education campus.

What were the principle differences between the education system in South Africa and Britain?

Classroom techniques are rather different and would be regarded as old-fashioned over here. Particularly in maths lessons, there is not much interaction between teacher and pupil, (or educator and learner as they are termed in SA) and even less between pupils. The lessons have a very basic format, and are rather repetitive. There is also a distinct lack of differentiation, and a lot of pupils’ needs are uncatered for – I asked about help and support with pupils with dyslexia or learning or behavioural issues that might impede their education, and was told that while officially each school had a policy and procedures to follow, the reality was that they were rarely implemented. In Britain, by contrast, when teaching, information on each pupil is usually readily available, and TA’s are often on hand for support with less capable pupils. I did not meet a single TA in Johannesburg. The technological resources that are being used increasingly in British schools are not seen in South African classrooms, where in many schools there are not even enough exercise books for the class. Despite these problems, an asset that Britain cannot claim is the attitude that learners have toward their education and the teachers. They are full of respect, enthusiasm and are determined and conscientious in their work. Education is not free in South Africa, and while this may be a key factor, having talked to a number of pupils it is clear that they recognise the importance of a good education, especially when trying to improve their quality of life and securing a steady job. Pupils are more open about problems they encounter with work, and willingly answer questions, probably because the response they receive from other pupils is rarely condescending, frequently encouraging. It was so refreshing to meet so many pupils with such a co-operative attitude in the classroom.

What were the major differences between the schools in the townships and those in the suburbs?

Throughout Johannesburg, the problems of drugs, violence, crime and AIDS are prevalent. Pupils in the suburban schools were often living in establishments like care homes affiliated with the school when conditions at home were bad. Two of the students on the trip were placed in a school in a notoriously violent area, and reported hearing gunshots while at school, and many of their pupils came to school having obviously been beaten. In township schools, living conditions were generally much poorer, and families struggled even more to pay for schooling. School buildings, especially, were bare and unwelcoming, some were heavily vandalised with smashed windows or even stolen doors. The lack of resources, as basic as chalk and exercise books was also lamentable, as it really held back progress in the classroom. While in the suburbs, pupils were keen to learn and receptive, in the townships the determination to succeed and the pupils hope for a better future was even more inspirational, as their motivation to do well in life is often to help their families and return to better their community. Teachers, too in townships, spoke of teaching as a vocation, as pay and working conditions were quite bad – they genuinely wanted to improve the lives of these poorer children.

How did South African teachers and children react to you?

Assisting in lessons and taking my own, my input was received well, not just by pupils but by teachers who welcomed new approaches and ideas. The readiness of all school members to learn from what I had to offer was outstanding, and not a little daunting, but I hope that the techniques I passed on to staff and pupils will help the learning of maths for years to come. As I have previously mentioned, the warmth with which the pupils received us was particularly outstanding, they were fascinated with every aspect of my life as a British student, intrigued by where I got my clothes from, what model my mobile phone was, what films I watched, what music I liked, what celebrities I liked and so on. What continued to surprise them was how similar my tastes were to theirs; and this was yet another aspect of my school experience that I particularly enjoyed – reconciling these African pupils’ worlds with my own. Speaking with them I was able to show them that we were not poles apart – that my achievements and progress in their eyes were not unattainable for them. I felt I was able to instill a belief in themselves and their capability to succeed, a sense of courage and confidence which is lacking in many pupils who feel trapped by their society and feel destined to failure. While they worked hard towards a goal of doing well academically, several were held back by their lack of self belief. Talking with them and doing my best to persuade them that a career, a happy family and a future without drugs, violence or AIDS was something they could have was extremely emotional and I hope that the attention the pupils paid to my words indicates that they took them to heart and will go on to succeed in life.

How were you able to make a difference to the lives of these children?

The way we were received in schools was almost as though we were celebrities at times. It was great to be in a position where, with the pupils hanging on your every word you could tell them that you really believed they could go far – I was so impressed that they actually seemed inspired by what I said to them, which was an incomparable feeling.

How has your experience in South Africa helped to define your career goals?

While I was passionate about teaching before, this programme has shown what an amazing impact teaching in less developed countries can have, and I am determined to invest more time and money into this sort of venture whenever I can. Another group member and I are currently working on a follow-up activity – sending resource packs including posters and activity packs to the township schools we worked with as well as others, in hopes it will reinforce the work we did and show pupils that we are still thinking of them and want them to do well. I hope to be involved with the SASSA project in future years, helping in any way I can to help the children of South Africa.

How will this experience influence the way you teach in British schools?

Being in classrooms with little to no teacher-pupil interaction has reiterated the importance of planning and conducting engaging lessons, and working to get pupils enthusiastic about a topic. In many ways it also helped me see how much influence you can have over pupils as a teacher, and so it is important to always make them feel valued and appreciated.

How would you like to see the SASSA programme evolve?

I believe the trip accomplished a lot, but feel there is even more that could be done to benefit the schools we visit in future. For example, sharing resources like exercise books and activity packs would be invaluable, especially in township schools. Obviously the more schools we can help, the better, but I would also advocate spending more time working with township schools, where our impact was greatest. Also, perhaps venturing to other less-developed countries to try and help where we can with their education systems is another way that students could help promote math learning for less privileged pupils.

How has your experience influenced your view of philanthropy and the value it has?

This opportunity was amazing, for the students who took part and the pupils and schools who we worked with. This opportunity would not have been possible without generous sponsorship, and I am so grateful to all the people who helped the programme become such a success. I think before this experience I was not aware of how much could be accomplished by people who, unable to get involved hands-on could aid a project like this by helping with funding. It has made me more inclined to donate my own money to causes like this, and to encourage others to get involved in any way they can. I believe the good work we started should continue and grow to touch even more, and provide the unforgettable experience I had for yet more students.

Corrinne Mackintosh, 3rd Year BSc Mathematics