Calendar

seminar: Dr Bradford Pelletier (College of Charleston) "Disappearing Before the Light of Science": Connecting Combat Experience and Insanity in the Nineteenth Century Asylum

Please note new time.

Refreshments served. All are welcome!

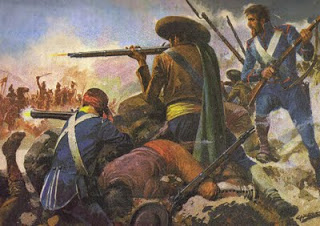

In 1794, Philippe Pinel received a patient whom he called “the furious soldier.” Terrified of returning to the French army, the soldier was confined – by force – to his cell. For the next several days, the soldier tore apart his cell, verbally berated Pinel as he made his rounds, and had to be physically restrained.

Likewise, after First Manassas – the opening battle of the American Civil War – Private Thomas E. Jones of the Second Regiment, South Carolina Infantry was discharged from the Confederate Army for “mania.” Months later, in September 1861, Jones was committed to the South Carolina Lunatic Asylum (SCLA). Physicians concluded – as they did for many veterans in the years following the war – that the “immediate cause” for commitment was “excitement on the battlefield.”

These findings are remarkable in that physicians within the burgeoning science of psychiatry made connections between insanity and war-time experience long before the advent of shell-shock in the wake of World War One. While some scholarship has mentioned anecdotal evidence of the cultural framing of trauma resulting from combat prior to 1918, few historical accounts have examined pre-twentieth-century veterans’ mental health from the American Revolution, through the Napoleonic Wars, to the close of the nineteenth century.

Preliminary research into pre-Freudian psychiatric pathology suggests two early conclusions; one, that proto-psychiatrists used war trauma to enhance their cultural authority, and two, that the veterans unevenly viewed their experiences in combat as a result of their own individual situations and the popular perception of society. In a time when the horrendous results of war forced physicians to better address physical injuries, this study shows that the effect of combat upon the psyche was impossible to ignore in American and in France during the early nineteenth century.