Nicolas Delamare

Download

Born in June 1639 in the small commune of Noisy-le-Grand – 19 kilometers east of Paris – Delamare died in the capital in August 1723 at the ripe old age of eighty-four; an astonishing achievement at a time when the average life expectancy was twenty to forty years of age. With his father, Guillaume, employed as a notary and several of his siblings working as practitioners, Delamare was raised in a fairly well-to-do family and was privileged enough to study law at a Parisian collège. Although never actually graduating from his degree, Delamare clearly had money to fall back on. Settling in Paris in 1664, Delamare used his legal training and financial resources to purchase the office of procureur for over 4,000 livres at only twenty-five years of age. Following the death of his father and brother Pierre, Delamare found solace in his marriage to Antoinette Saviner in 1670 with whom he produced three children, two girls and a boy. As well as a union of love, Delamare’s marriage also secured a future career move. Saviner’s family were both wealthy – possessing 5,000 square meters of vines in Poissy – and well connected with Jean Lecerf, Antoinette’s cousin, working as commissaire examinant of Paris. It was surely not coincidental that three years after their marriage, Delamare was able to buy his way into a commissarial office at the Châtelet for 25,000 livres. Delamare’s swift progression through the administrative ranks clearly demonstrated his talent and ambition to succeed, qualities that Louis XIV was quick to take advantage of. Le Roi-Soleil handed Delamare the charge of inspecting financial corruption in the construction of Versailles, and was made responsible for appeasing popular unrest and ensuring grain supplies during subsequent periods of dearth in 1693, 1699-1700 and 1709. Assured in his administrational capacities, Louis XIV even entrusted Delamare with the household intendance of his bastard child, Louis de Bourbon, a figure of public disgrace for his homosexual relationship with the Chevalier de Lorraine. Perhaps Delamare was seen as a good influence that might set his son’s ill-behaviour straight.

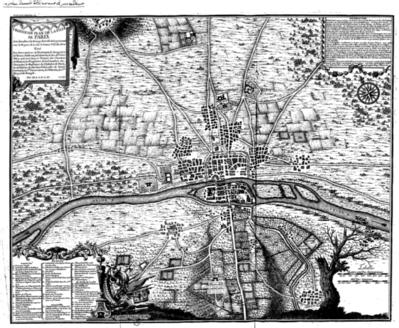

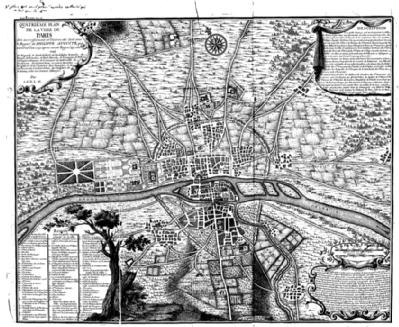

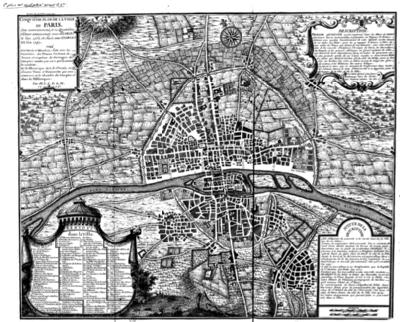

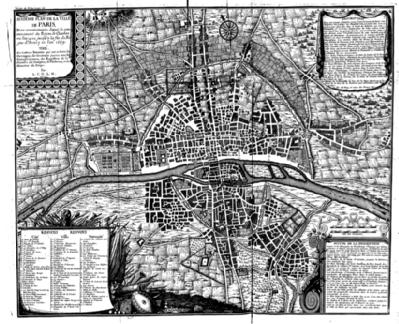

Illustrations from Delamare's Traité de la Police, vol. 1 (1705)

4 plans showing the expansion of Paris from early 12th to early 17th century, Traité de la Police, vol. 1 (1705)

Delamare achieved fame with his Traité de la Police, published in four volumes between 1705 and 1738. From his rigorous exploration of the Paris archives, Delamare's monumental work – comprising over seven hundred folios decorated with intricate illustrations, maps and detailed annotations – set out every ordinance, arrêt and regulation concerning the police and public order of the city from Antiquity up until Delamare’s present (eighteenth-century) day. His research experience was clearly one that even today’s historians would sympathise with:

[My sources] are spread across such a great number of Volumes: all of which for that matter are incomplete, & mixed with so much irrelevant material, & with so little order, that it requires a very great effort to do research.[1]

In his broad survey of the necessary roles and functions the Police had assumed in regulating the social, political, religious and economic lives of the city’s inhabitants from time immemorial, Delamare did not intend for his work to be a simple point of reference for Parisian magistrates. Across the many centuries he studied and the different periods of peace and war, plenty and scarcity, and health and sickness he commented on, Nicolas Delamare employed history to teach the police of Paris a lesson that would be carried forward:

It is chiefly from past events”, Delamare concluded, “that we can draw the rules of security, & conduct for the present, & for the future”.[2]

Further reading

N. Dynoet, ‘Le commissaire Delamare et son Traité de la police’ (1639-1723)’ in C. Dolan, Entre Justice et Justiciables: Les Auxiliaires de la Justice du Moyen Âge au XXe Siècle (Presses Université Laval, 2005), 101-20.

C. F. Lambert, Histoire Littéraire du Règne de Louis XIV (Paris, 1751), 409-13.

N. Delamare, Traité de la police, où l'on trouvera l'histoire de son etablissement, les fonctions et les prerogatives de ses magistrats; toutes les loix et tous les reglemens qui la concernent... (Paris: J. et P. Cot, 4 vols., 1705-38). Volumes 1, 3 and 4 are electronically accessible via Gallica (http://gallica.bnf.fr/).