Newton’s World: A Digital Map for Teaching the History of Early Modern Science

Published: 26 August 2022 - James Poskett

Isaac Newton is perhaps the most famous figure in the history of science. In his Principia Mathematica (1687), Newton set out the laws of motion, explaining how gravity operated with mathematical precision. Today, school children all over the world are taught Newton’s laws, even if not through the dense Latin text of the original.

Understandably, Newton features heavily in the teaching of the history of science. And the place of Newton in the history of science has been at the core of many important historiographical debates. Was Newton a lone genius? Was he a product of a particular intellectual context? Or perhaps he was conditioned by the wider social, political, or even economic context? Is he best understood within an English, or European frame? Or is there a wider colonial or global context at play here? These are the kind of questions that historians of science, and students taking history of science courses, have been asking and answering for decades.

Like many of us, I’ve been preparing my teaching for the coming academic year. I’m planning on giving a lecture on early modern science as part of our Galleons and Caravans: Global Connections, 1500–1800 module. I was thinking about how to present these debates on Newton, particularly to a group of students who may have no previous experience in the history of science, but are certainly interested in global history.

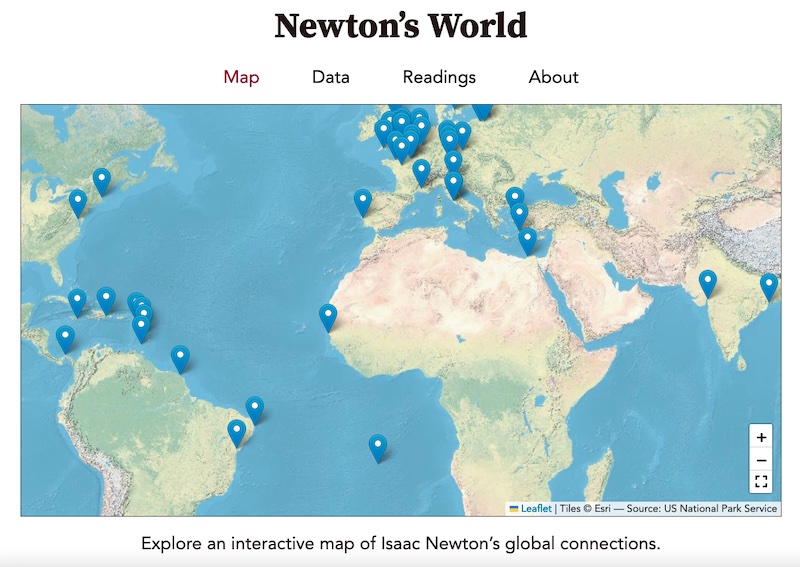

Recalling a brief former stint as a computer scienceLink opens in a new window student, I spent a few days putting together an interactive map that is now available online. I hope it will be a useful resource, not just for my students, but for anyone teaching the history of science, or indeed global history.

You can check it out here: https://isaacnewton.world/Link opens in a new window

The idea behind the map is to introduce students to all the different kinds of connections which went into making Newton’s Principia, stretching from Maryland to Vietnam. It is very much designed as a teaching tool, and certainly not a scholarly edition. I deliberately did not include any additional interpretation—just the core information of when, where, and who Newton was getting his information from, along with a short extract from the Principia.

Students are therefore invited to uncover and reflect on the significance of these connections themselves. They might be asked (or ask) questions like:

- Why was there a French astronomer in West Africa?

- How did Newton collect information from Vietnam?

- Why did Newton cite a 12th-century copy of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle?

As historians of science will be aware, the map builds on the incredible work of Simon SchafferLink opens in a new window, who in an important 2009 articleLink opens in a new window made the case that Newton’s work could be understood as part of a global ‘information order’. Newton, who never left Britain, was in fact connected, not only to Continental Europe, but also to the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific worlds. This history, necessarily, also meant acknowledging the connections between Newton, slavery, and empire, something Nicholas DewLink opens in a new window in particular has played a major role in highlightingLink opens in a new window.

Alongside the map, I’ve put the core data into an Excel spreadsheet and a plain text array. Both are free to downloadLink opens in a new window, released under a Creative Commons License, so feel free to do as you please. As I said, I put the website together as a teaching tool, with minimal interpretation. But there are all kinds of things researchers and students could do with the data. A subset of the data, for example, could be used as part of a project to highlight the links between Newton and slavery. Another subset could be used to explore Newton’s interest in ancient and medieval texts.

If you have any additions, corrections, or suggestions, please do get in contactLink opens in a new window via email. And if you use this webpage in your teaching or elsewhere, I'd love to hear about it.