Queen Pin: The Woman Who Ran the Border Drug Trade

Published: 21 October 2022 - Benjamin T. Smith

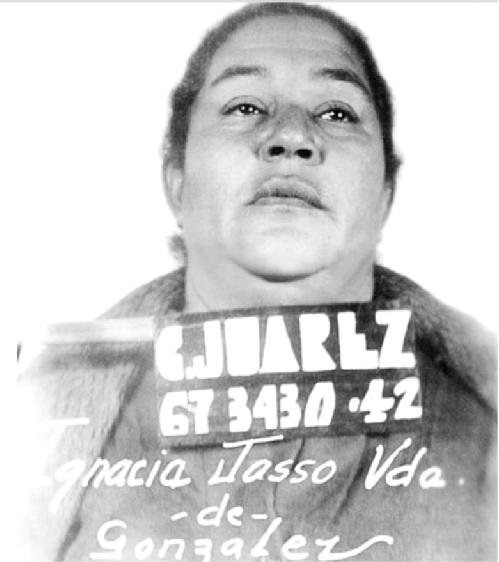

Figure 1: La Nacha, prison photo, 1942

Drugs, we think, are a man’s game. Men brandish machetes to cut the leaves from marijuana and coca plants. They lug the sacks of product up to highland labs, where they dry it, process it, test it, and pack it. Then they transport it on vast staggering mule trains or weld it round the oily drive shafts of aging cars or force it into petrol tanks, or food cans, or small, swallowable condoms. Most importantly they fight for it, for the money it generates and the power it gives. They fight for it in drunken bar room brawls, in claustrophobic hotel-room scuffles, and carefully-planned hits. Now, more and more they fight for it on the streets, informal generals heading their own ragtag armies of young, gun-wielding killers.

Nowhere has this been clearer than in the border city of Ciudad Juárez, where over the past two decades battles between cartels and between cartels and the police have left 30,000 dead and nearly 10,000 disappeared. Well over 90 per cent of these have been men, attracted by the money, pushed by their peers, or cajoled at the barrel of a gun. No doubt, women have been killed too. But they are the victim’s victims. They are the sex workers, the girlfriends, the factory workers, the secretaries, and the sisters sucked into this world of macho violence, used, abused and then churned out the other side. Narcos get corridos; their heroism lives on; their friends howl out their songs to commemorate their bravery. Ciudad Juárez’s dead women get none.

Yet this was not always the case. For fifty years one woman, Ignacia Jasso aka La Nacha, dominated Ciudad Juárez and much of the U.S. southwest’s drug trade. She moved up drug trafficking’s shaky hierarchy from gangster’s moll and small-time dealer, to vice center wholesaler, to drug provider for much of Texas, Arizona and the east coast. By the 1960s her children and her grandchildren were in charge, moving from morphine and heroin to weed and cocaine as the market demanded. In 1955 one heroin addict at Senate Hearings in San Antonio described her as “the head of everything… everything that goes in and out of Juárez goes through her”. A decade later a retired U.S. Customs officer thought her so powerful, so mysterious, so all-encompassing that “to say La Nacha is like saying the Mafia”. By 1972 her grandson, Hector Ruiz Gonzalez aka “El Arabe”, was the U.S. drug agency’s second most wanted man.

My research trip in July 2022 to Mexico City is the first part of an effort to write a biography of La Nacha and her family. As a true crime biography, it is designed as a thriller, a game of cat and mouse between a shifting group of U.S. and Mexican cops and a criminal mastermind. It includes the usual litany of betrayals and shoot outs, shady payoffs and backroom deals, street level grime and glitzy excess. But, like my last book, The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade, it is also a serious work of history. As such it interweaves La Nacha’s story with broader histories of the border, the drug trade, politics, policing, U.S. demands, Mexican sacrifices, and the role of women in this fraught relationship.

Three elements of the book stand out. First, this is the story of U.S. prohibition that your teachers never told you. Between 1900 and 1920, U.S. policy makers, on the federal and the local level, banned drugs, booze, gambling and sex workers. They tried to usher the great unwashed masses into an imagined middle class. In doing so, they created what one historian has called “the Prohibition regime”. These policies birthed the modern American state, its powerful federal agencies, its baton-swirling neighborhood cops, and its right to monitor and mess with the private lives of its citizens, especially those of colour. They also generated its inverse. They included a new underground economy and new enemies from small time “hopheads” and rum runners to Al Capone, Lucky Luciano, the enormous, interlinking network of Mafia families and the political friends that protected them.

But U.S. prohibition also did something else, something unintended and ignored. As legislators banned U.S. vice with a stroke of a pen, they simply sent it a couple of miles south. America’s problems became Mexico’s. Sleepy agricultural towns, like Ciudad Juárez, Tijuana, and Mexicali, became vast vice centers almost overnight. They catered to what Americans desired but didn’t want to see. With U.S. money and Mexican labour, they built bars, brothels, horse tracks, betting shops, and opium dens. And they populated them with a generation of Mexicans fleeing the violence and hunger caused by the Mexican Revolution. Furthermore, even as the harsher prohibition laws were revoked, America’s insatiable demands continued to shape these new underground geographies. Women and morphine for the American GIs; goofballs, jazz bars and strip joints for 50s party kids; weed and heroin for the hippies and the Vietnam vets. Women like La Nacha were at the center.

Second, this is the story of narco-entrepreneurialism. As high-value commodities, drugs are always at the forefront of economic developments. But change is gradual; most drug traffickers specialize; or if they do move trade, they follow set patterns and approaches. Not La Nacha. La Nacha was always moving - shifting suppliers, moving trafficking routes, changing distribution networks, renegotiating political protectors. She was the first Mexican trafficker to tap Chinese opium cooks to work on homemade Mexican morphine. And when they were caught, she travelled south to Mexico’s pharmaceutical capital of Guadalajara and hooked up with a former police chemist. When U.S. and Mexican pressure closed down her selling spots in Ciudad Juárez’s vice district, she invented the first Mexican shooting galleries, or picaderos, employing legions of fellow widows to inject American GIs in makeshift rooms at the back of their houses. And when the market moved from heroin to marijuana, it was her grandson, El Arabe, who led the way, teaming up with a group of U.S. pot smugglers to feed tons of weed to the east coast.

Figure 2: La Nacha, Prison Photo 1930

Third, this is the story of survival – and perhaps most poignantly in Ciudad Juárez of a woman’s survival. Over the decades, La Nacha faced down innumerable obstacles. She should, as she claimed on her deathbed, have been killed many times over. She should have ended just another Juárez statistic, another woman without memorial.

But she didn’t. Widowed at the age of 30, her gunman husband blown away in a bar room shootout, she swore vengeance on his killer, commissioned the first narcocorrido in his honor, and moved fulltime into the drug business to provide for her children. Confronted by the city’s reigning kingpin, she dodged bullets and made friends, securing the support of the state authorities, and teaming up with the police to wipe out her competitors in Mexico’s first drug massacre. In the early 1940s, she even defied the attentions of America’s drug tsar, Harry Anslinger, who declared her public enemy no. 1. He even tried his hand at making her subject to the first drug extradition. La Nacha, however, survived. In her later years, she confronted Senate investigations, local drug peddler purges, the shift towards the new counterculture drug market and most fearsome of all – the combined violence of the DEA and their Mexican federal cop allies.

Product of America’s desires, victim of its prejudices, survivor, the story of La Nacha is the story of the US-Mexican border in the twentieth century.

Research Trip: Mexico City, July 2022

Researching the illicit drug business is a tough business. Sources are scarce. Interviews are difficult to get. And documents tend to be written to back government policies and demonize and caricature drug traffickers. Writing about La Nacha is no different. For Anslinger she was “a short, dark, swarthy woman” who was “poisoning both the American and Mexican people”. For one Mexican president, she was so dangerous, he changed the law to automatically allow federal authorities to send drug criminals to the prison island of Islas Marias.

Yet it is possible. In my previous work I have scoured secret service, police, and state archives on both sides of the U.S. border. I have also carefully parsed the work of contemporary Mexican journalists, and particularly writers of the nota roja or crime news. Crime newspapers were Mexico’s most popular and open journalistic fora. They investigated and wrote the news the broadsheets wouldn’t touch. They refrained from alarmist moralizing and instead balanced the social effects of organized crime. They uncovered the secretive links between politicians and criminals, and often, paid for this with their lives.

In July 2022, supported by Global History and Culture Centre funding, I went to look for investigations of Ciudad Juárez’s drugs and crime scene in the crime newspapers held in Mexico’s premier newspaper library, the Hemeroteca Nacional. Here I spent my time on national tabloids and crime rags like Detective, Alarma and La Prensa as well as local crime newspapers like La Semana, El Alacrán and Ese Justicia.

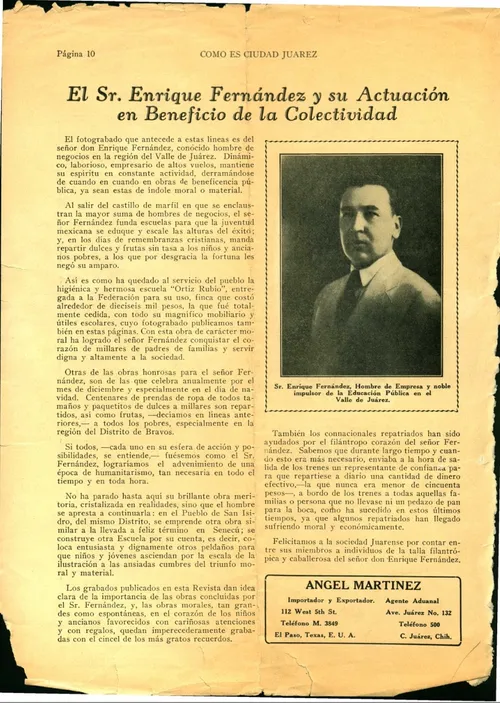

Some findings stood out. First, I managed to piece together some of the philanthropic projects of La Nacha’s first boss, turned rival Enrique Fernández. During the 1930s, he secured his criminal empire by widely and publicly investing in schools, orphanages, and gifts for local children. Such exercises set a pattern for La Nacha and other border drug traffickers, who used such tactics to shore up popular support and faced down political attacks.

Figure 3: La Semana, Ciudad Juárez, 31 January 1934

Second, I started to use the newspapers to piece together how La Nacha’s grandson, El Arabe, took over the family business during the 1960s. He not only got involved in the emerging marijuana trade, buying up plantations in Sinaloa and selling product to a network of EL Paso hippies, he also expanded on La Nacha’s shoot galleries or picaderos, expanding them out of La Nacha’s barrio and into the center of the city.

Third, I started to use Alarma to gather information on Ciudad Juárez’s vice scene in the 1960s. In 1965 the magazine started to employ a local journalist, Daniel de los Reyes, as a stringer for the magazine. His stories were explosive. They recounted back alley deals between La Nacha and the local police, payoffs to the American authorities, and a municipal government run almost entirely on the profits of the narcotics and sex work trade. Such stories brought trouble and De los Reyes was threatened, beaten and eventually ended up in the Ciudad Juárez jail. It was only after a national campaign to release him that he finally walked free.

Benjamin T. Smith is Professor of Latin American History at the University of Warwick. His previous books have explored politics, violence, Catholicism and journalism in modern Mexico. Benjamin has written widely on Mexico for The Guardian, Jacobin, and Dissent and has appeared on Sky TV, BBC Radio, Channel 4 News, and France24. He also provides expert witness accounts for Mexican asylum seekers escaping gang violence. Benjamin's latest book, The Dope: The Real History of the Mexican Drug Trade, was published by Ebury and Norton in 2021.