Archaeology, Antiquity, and the Making of the Modern Middle East: Global Histories 1800–1939

Published: 3 August 2023 - Guillemette Crouzet and Eva Miller

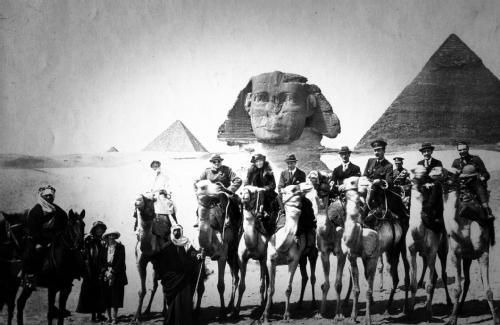

The ‘Middle East’ is both a geographical descriptor and a much grander conceptual designation, associated with emerging empires, antiquity, antiquities, and the forging of modern political, religious, ethnic, and national destinies. What competing imperial, national, and transnational narratives about the present and future of this geopolitically crucial region were fed by archaeology, philology, and history? How were these emergent disciplines themselves forged through Middle Eastern contexts they purported to study? How were temporalities of modernity and progress constructed in relation to the ruptures, continuities and heuristic challenges suggested by the excavation and exegesis of traces of ancient civilisations? How did the return of the remains of the past assist Western and Eastern empires, and new Middle Eastern countries in understanding their own futures?

To engage with these questions, we convened the conference ‘Archaeology, Antiquity, and the Making of the Modern Middle East: Global Histories 1800–1939’ on 25–26 May, 2023 at the University of Warwick. As the annual conference of Warwick’s Global History and Culture Centre, it brought together attendees with a particular interest in the Middle East, archaeology, or imperialism, with those with a broader interest in global history, history of science, or imperial or postcolonial histories.

We began and ended the conference by thinking about why a conference on one area of the globe belonged as the annual conference of a centre for ‘global’ history and culture. As a region so often figured as part of the ‘origin’ of various world historical landmarks (a ‘cradle’ of civilisation, writing, empire, cities, and art), the Middle East has often been understood as crucial to the history not just of itself, but of the world (or perhaps particularly European powers that considered themselves leaders of that world). Our conference explored how the Middle Eastern past has been claimed by and for the world and what this has meant for the political and national destinies of people living in these regions. A final roundtable which closed the conference ‘Whose Heritage? Living with the Legacies of Imperialism, Colonialism, and Nationalism in the Middle East’ explicitly critiqued the notion of the Middle East’s past as ‘global heritage’.

Speakers, chairs, and organisers came from institutions in the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Israel, Egypt, Iraq, France, Germany, Italy, and Switzerland. Speakers ranged from emeritus professors who have contributed foundational, agenda-setting work to current doctoral students presenting results of emerging research projects.

The conference was an unqualified success. As organisers, we were especially pleased not just by the incredibly high quality of the papers presented but also by how well they cohered. Common themes were picked up across papers. Participants had submitted longer drafts in advance which contributed to the clarity of the arguments they made, and the overall quality of discussion. Discussions after each panel, during the roundtable, and informally throughout the conference picked up on a few themes that we will highlight here.

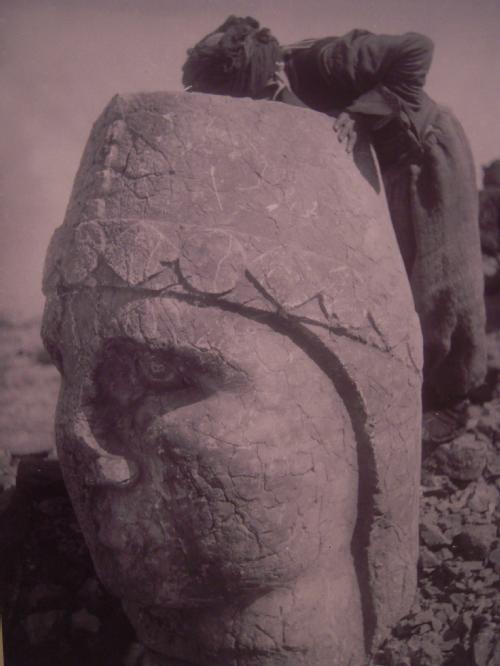

Extraction, development, preservation

Robert Vigar and Amany Abd el Hameed contrasted British preservationist rhetoric with the reality of the ‘extractivist’ nature of British colonial-era archaeology. Parallels between the extraction of oil and the ‘resource’ of antiquities (or ‘antiquity’ itself, in a historiographical sense) were noted by many. Lynn Meskell and Erin O’Halloran pointed out the practical overlap between oil workers and archaeologists: sometimes, they literally shared equipment or trained each other. Fresh from a visit to Kirkuk in Iraq, Eleanor Robson pointed out that archaeological sites and oil extraction sites can exist so close to one another they are virtually indistinguishable.

Papers by Billie Melman and Sarah Irving demonstrated how colonial and post-colonial ideas about ‘development’ encompassed the development (destruction and extraction) of heritage sites. Archaeological sites were treated as a resource for development and exploitation in the efforts to bring Middle Eastern countries into modernity. Artefacts extracted from archaeological excavations have been regarded by imperial and postcolonial actors, such as UNESCO, as global commodities, which are in danger of looting, but also eligible to be bought, sold, or exposed in museums and galleries. They have a value on the market, just like oil. Global heritage sites are in some way perceived in the same vein, as locales where history and monuments are ‘marketable’ commodities.

Money, value, trade

Sarah Griswold pointed out that it is strange how often scholars overlook something that looms very large in most of our lives: money. How did people make a living from antiquities? How was the value of antiquities measured? Griswold, Nicole Khayat, and Vigar and Abd el Hameed all presented studies that showed how administrators, no less than later scholars, have often struggled to adequately determine what substantially distinguishes ‘looting’ from many types of archaeological extraction. While designating objects as antiquities or ‘world heritage’ often made them monetarily worthless to ordinary traders (if, legally or practically they could not be traded), it also rendered them ‘emotionally priceless’. And yet states no less than individuals weighed up real costs when it came to heritage. Several speakers highlighted that British colonies and mandatory powers were run ‘on a shoestring’. Debbie Challis showed how the English curator-excavator Thomas Newton justified the expense for moving the stones of Halicarnassus to the British Museum by promising that they would repay the home economy, in part by inspiring British art and architecture and stimulating these areas economically.

Warfare and conflict

In a sobering keynote on the first day, Lynn Meskell traced the practical, as well as ideological, imbrication of archaeology, war, and nation-building in the Middle East in the era around the First World War. Incorporating new insights from archival research in only recently available letters of T.E. Lawrence, David Hogarth and other archaeologist-spy-diplomats, Meskell revealed how archaeological and military technologies and perspectives birthed new forms of violence. Particularly striking to attendees, and much discussed, was Lawrence’s advocacy of carpet bombing on Iraqi and Kurdish villages—a suggestion derived from the aerial gaze enabled by flight, a technology which simultaneously made the past visible and (so Lawrence seemed to suggest) the human cost of warfare invisible. Lynn Meskell’s keynote showed brilliantly the blurry line between archaeology and imperialism, by analysing Hogarth’s and his protégé’s contribution to the Sykes-Picot negotiations during the First World War which carved the Middle East, around a geography of oil sites and archaeological sites. Archaeologists not only helped rewrite the Middle East past, they also forged the political future of the region and drew borders together with diplomats and heads of imperial states. Solmaz Kive’s analysis of the Iran Bastan museum also showed how European archaeologists, despite their violent legacy, still loom large in the history of heritage in Iran. Built under the Pahlavi dynasty which is known for having made use of the Achaemenid past to legitimise its own rule, the museum still has galleries names after two French archaeologists, Jacques de Morgan and Marcel Dieulafoy.

As Erin O’Halloran pointed out, the use of the Middle East as a ‘testing ground’ for new technologies of killing is one that is being repeated today, as techniques employed in the ongoing Syrian Civil War have moved to the war in Ukraine. O’Halloran’s study of three different modern Middle Eastern nations also demonstrated this flexibly, and the centrality of archaeology to nation-building in the aftermath of war and conflict, while Marwan Kilani’s exploration of Lebanese ‘Phoenicianism’ showed how the concept of a Phoenician connection was a paradigm that adapted itself to different agenda in times of warfare and conflict and times of relative stability.

‘Local’ knowledge

We had hoped to find scholars who were able to give us perspectives beyond, or beneath, the level of state actors, and this is where research presented at the conference had the most new insights to offer. Debbie Challis opened proceedings by showing a map of the Mausoleum of Halicarnassus, in present-day Turkey, as it existed in the mid-nineteenth century, offering a new way of seeing a famous archaeological site of the ‘Classical past’: as a site of Turkish homes, which were destroyed or even tunnelled into without permission by British excavators. Daniel Foliard read Austen Henry Layard’s popular accounts of his 1840s excavations in Nineveh ‘against the grain’, incorporating insights from Mosul’s social history, to reveal the political practicalities that lay behind local resistance to Layard’s excavations, as well as showing just what kind of books were being written and read in Arabic in Mosul at the time about the region’s past.

Nora Derbal countered the German travel writer Heinrich von Maltzan’s accounts of North African ‘disinterest’ in Phoenician antiquity by pointing out that he was denied access to ancient inscriptions precisely because a local Ottoman ruler wanted to collect and publish the inscriptions himself. Laith Shakir contested the widely-accepted historiographical narrative that Iraqi interest in archaeology arose only belatedly and only in response to European paradigms, by revealing a strong and multifaceted interest in archaeological developments in Iraq in both the local and regional Arabic press. Nicole Khayat, working in part from family archives, presented a case-study of a Palestinian antiquities dealer (her great-grandfather) who conducted excavations not only to find pieces to sell, but also as a means of community building, and out of a historical-antiquarian interest in ancient artefacts. Heba Abd el Gawad spoke about her role as an ‘indigenous Egyptian’ scholar of ancient Egypt, and the contradicting demands such an identity places on her. She highlighted her weariness at having to prove over and over again that Egyptians care about their own history. At the same time she questioned why Egyptians should necessarily have to care about their heritage only within the paradigms laid down by European archaeologists.

Zeynep Çelik’s keynote on the second day, which looked at provincial Ottoman museums and antiquities storage, and the movement of antiquities from local sites to Istanbul, also offered a tantalising new perspective. Provincial towns created ‘museums’ within high schools, police stations, or other municipal buildings. While the Istanbul Museum might emerge as a towering edifice of imperial self-fashioning (as Solmaz Kive also showed to be the case with the Iran Bastan Museum), small provincial museums had an entirely different setting and would have been encountered in entirely different ways by the communities in which they were located.

Whose Heritage today?

The roundtable, ‘Whose Heritage?’ also put the idea of the ‘global’ in tension with realities on the ground. All panellists pointed out how discourses of ‘global heritage’ have contributed to the erasure of local traditions and claims to objects and site management. International heritage bodies can seem completely disconnected from the locations they put on the global map of tourism, for instance, prioritising sites that are not the most meaningful to individuals actually living among them (valorising ancient archaeological sites over historic mosques or marketplaces, for instance). Professor Lynn Meskell described the results of a recent study she had conducted at the University of Pennsylvania which indicated that for almost 1,200 World Heritage sites worldwide, the inscription of global heritage had actually increased conflict, rather than cooperation.

Panellists introduced other concepts for consideration: Ammar Azzouz discussed his work on the concept of ‘home’, suggesting that heritage prioritisation must focus on preserving and creating the sense of safety and security connected to that simple, fundamental concept. Heba Abd el Gawad, expanding on points she made in her own talk, emphasised the significance of multivocality, of listening to different, highly local, personal, or communal responses to antiquity and its remains. Mirjam Brusius questioned what it mean to talk about globalness in a world where scholars were still divided unequally by national borders and infrastructure deficits.

Rozhen Mohammed-Amin offered a more constructive interpretation of what a shared sense of heritage might look like. She explained how a focus on storytelling and technology can encourage a different sense of ‘ownership’ of past heritage through provoking empathy. Rather than erasing the local and particular, empathy opens the possibility for connection, and develops a sense of collective responsibility. Projects she has worked on in Iraq have done this through prioritising local voices, soliciting feedback, and remaining focused on the potential heritage work can have for constructive, reconciliatory dialogue.

Dr Guillemette Crouzet is postdoctoral research fellow based at the European University Institute in Florence, working on the ERC project “CAPASIA: Capitalism in Asia”. She is a historian of Britain and the Middle East in the modern period.

Dr Eva Miller is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at UCL History Department, working on the reception and reconstruction of the ancient Middle East in the modern West.