Week 1 - what is a language?

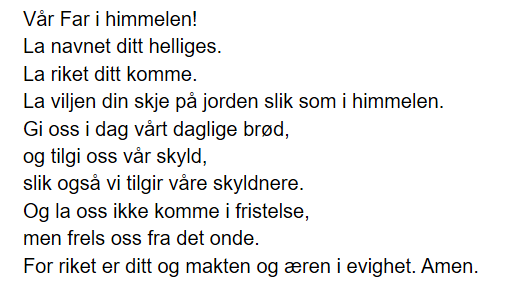

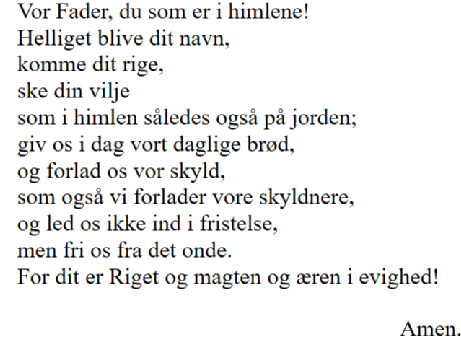

The paper we are looking at this week was written by a Norwegian-American academic in 1966, but it continues to be relevant today. He was considering Norwegian, which at the time was becoming important again after many centuries of Danish being the prestigious language in Norway, because Norway had become independent of Norwegian rule. You can see how similar the two languages are in writing (they are pronounced quite differently) here - the first Lord's Prayer is in Norwegian Bokmaal and the second (underneath) in Danish:

This paper discusses the different labels ‘language’ and ‘dialect’, and it introduces the concept of the ‘nation state’. Before reading it you may want to watch the following YouTube lecture by Professor Juergen Handcke at the University of Marburg in Germany. In it he introduces the concept of mutual intelligibility:

Once you have done that, the link to this week's paper is below:

Haugen, Einar, 1966. "Dialect, Language, Nation". American Anthropologist 68:4, 922-35.

As you read the paper, think about the following questions:

- On page 922, Haugen asks

Do Americans and Englishmen speak dialects of English, or do only Americans speak dialect, or is American perhaps a separate language? Linguists do not hesitate to refer to the French language as a dialect of Romance.

Is there a case to be made for treating American English as a separate language from British English? Make some notes about how we might defend calling them two separate languages – what grounds would we give for this?

Students responded using mutual intelligibility as an argument here. They rightly pointed out that if Standard British English is a dialect, we can reasonably argue that Standard American English is too. They also noted that the main differences between the varieties are lexical, with only some grammatical variation (got/gotten, if I had/if I would have). They did say though that perhaps speakers of American English dialects might struggle with some dialects in Britain and Ireland, just as we might struggle with Southern American dialect or Appalachian English.

- Where does Haugen say that the earliest use of the terms ‘language’ and ‘dialect’ appear in English and which languages did we borrow these words from?

- On p923, Haugen reports that “there was in the classical period no unified Greek norm.”

Can you think of a time when English had no unified norm?

Students pointed to the time before mass literacy and the printing press (the printing press was used in London first in 1476 and in Edinburgh in 1508). Although there were forms favoured before this time (the East Midlands dialect was becoming fashionable in London) it's true that having a machine to print did help standardise the language, though a lot of spelling variation remained. Others argued that especially in speech and in the informal registers there is little standardisation between dialects of English even today - this is a very good point. Pronunciation varies a lot across dialects, as does morphology and syntax. The rise of dictionaries and grammar books also helped to codify (fix a written form) and standardise English, but speech is much harder to police.

How do we make norms in English now and who is responsible for upholding these norms?

- What does Haugen mean by synchronic and diachronic?

- On p924 Haugen reports that the best translation for ‘dialect’ in French is patois. He talks about different written standards before France was unified. Does a country unifying politically always result in languages being standardised and differences becoming smaller?One student responded that where there is a genuine threat of a specific region rebelling or gaining independence... the state would attempt to replace any regional languages with the central governing language. indeed we can see many cases where the state does not only suppress regional languages but replaces them with a language not widely spoken across the country - Afrikaans in South Africa, Russian across Lithuania, Latvia and many other former states of the USSR which are now independent. They may also allow regional languages some status but usually reserve highest status for one language which they choose.

- Is Haugen correct in his assertion on p925 that

a dialect is a language that is excluded from polite society. It is, as Auguste Brun (1946) has pointed out, a language that “did not succeed.”

Students argued that a dialect was just one version of a language and that Standard English itself is a dialect. This is linguistically true but not socially true - Standard English remains prestigious across the Anglophone world, and dialects are usually not written as much, used in less formal domains and not included in educational settings.

Others argued that for a linguist doing historical linguistics, Old English is really just a dialect of Germanic, and indeed this was true for many centuries - Dutch and German speakers might have been able to understand much of what Angles, Saxons and Jutes said. In other words, time can change the shape of a language (speakers change it over time) and status can change over time.

In addition, students wondered about speakers who do not have a distinction between language and dialect (or only recently made one) - how does this affect their perception? Is dialect constantly feeding into the standard language, perhaps, does change happen 'from below'?

- On p926 Haugen talks about linguists having to abandon the idea that dialect areas were separate and distinct as it became clear that regions often shared some linguistic features and differed in others. Can you think of dialect features in the region you come from which ONLY happen in your region, and some features which the regional dialect shares with other regional dialects?Think about lexis (words), grammar (sentence structure), and phonology (the way words are pronounced)One student cited Geordie dialect here - like Scots, it did not go through ther Great Vowel Shift so that Newcastle United FC's fans are called 'The Toon Army' and Brown Ale is known as 'broon.' Older speakers from Newcastle and Northumbria may share grammar and lexis with Scottish speakers - a whaup is the old name for a curlew on both sides of the border, getting the messages is doing the shopping for older speakers on both sides, and the vowel reflex we discussed earlier happens in both countries.

- Haugen goes on to talk about the connections languages can have with nations. He reports (p. 930) that in Europe, “…as the people developed a sense of cohesion around a common government, their language became a vehicle and a symbol of their unity.” How good an example of the situation around the world do you think Europe is? Are there multilingual nations whose population identifies with more than one language?

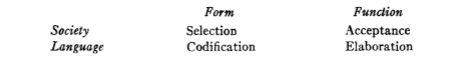

- Haugen finally talks about processes of standardisation and proposes what is now a very famous table of theory to show how standardisation takes place:

He argued that society had to select a language to be the standard, and this could only happen if the majority of powerful people wanted that language.

The language then needed to be codified - this involves it having a writing system, a grammar seen as 'correct', a set of words seen as belonging to the language, a set of punctuation rules and possibly a standard way of pronouncing the language.

How has English become codified in Britain and Ireland - that is, what sources do we all use to tell us how English should be spoken and written?

You can focus on just a few of these questions or attempt to discuss them all, and you may want to discuss them with others. Once you have mulled them over you are welcome to email me esther,asprey@warwick.ac.uk with any insights. I'll publish highlights of these plus my own thoughts next week (22.5.20) and post the next paper. Good luck!