module 1

Welcome to the first part of this course.

This page provides you with online material to reinforce, and in some cases extend, the discussion and activities carried out with your course leader. The aim of the certificate is to support you in developing your practice in a systematic manner. Before beginning the course you may want to think about the strengths and areas to develop in your practice as well as successful strategies for your own past professional development. This first part of the course provides an orientation to approach to professional learning called action research and we look at:

What is Action Research?

Why Action Research?

Tensions within Action Research

What is wrong with Action Research?

Who will Action Research appeal to?

What is difficult about Action Research?

Steps in action Research:

(1) What is the problem

(2) Reconnaissance

(3) Focus

Final Thought

Notes

What is Action Research?

(Stenhouse, 1984) (1)

| The term “Action Research” was coined and popularised by Kurt Lewin in 1946: “The research needed for social practice can best be characterized as research for social management or social engineering. It is a type of action-research, a comparative research on the conditions and effects of various forms of social action, and research leading to social action.” (2) The potential of action research as a process by which teachers in schools might improve upon their own practice was highlighted by Stephen Corey in 1953 (3). |

Kurt Lewin |

Corey saw the introduction of action research into education as a democratic move from outsiders carrying out research to teachers carrying out research in a collaborative and systematic, even scientific, way. In the following decade, however, action research dropped out of favour, being perceived as too radically politicised. It was not until as late as the mid 1970s that action research was advocated within Britain, primarily by Lawrence Stenhouse , who saw it as process of emancipation from the externally imposed pressures which learners, teachers and schools operated under. Nowadays action research is no longer necessarily associated with radical bottom-up democratisation and indeed is endorsed as a methodology for reform by government agencies (4) such as the Department for Education and Skills

, who saw it as process of emancipation from the externally imposed pressures which learners, teachers and schools operated under. Nowadays action research is no longer necessarily associated with radical bottom-up democratisation and indeed is endorsed as a methodology for reform by government agencies (4) such as the Department for Education and Skills .

.

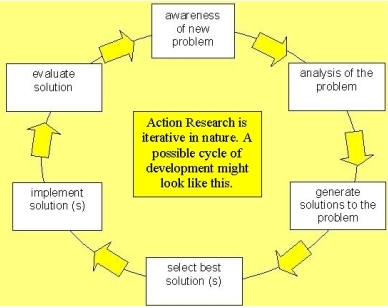

Various definitions of action research can be found in the literature including, amongst others (5):

Action Research is a three-step spiral process of (1) planning which involves reconnaissance; (2) taking actions; and (3) fact-finding about the results of the action.

Kurt Lewin (1947)

(1947)

Action Research is the process by which practitioners attempt to study their problems scientifically in order to guide, correct, and evaluate their decisions and actions.

Stephen Corey (1953) (3)

Action Research in education is study conducted by colleagues in a school setting of the results of their activities to improve instruction.

Carl Glickman (1992)

(1992)

Action Research is a fancy way of saying let's study what's happening at our school and decide how to make it a better place.

Emily Calhoun (1994)

(1994)

Central to the different definitions that can be found are the following concepts:

- It is research by teachers that addresses a problem that they have identified as being of concern to them.

- It is a process that involves problem identification, design, implementation evaluation and identification of new problems.

- It typically involves collaboration between colleagues.

Other descriptions and models of action enquiry also exist, such as the following.

|

|

|

Planning ![]() Acting

Acting ![]() Observing

Observing ![]() Reflecting

Reflecting

Why Action Research?

The best argument for using action research is that it can make a difference to teachers and lead to practical improvements inside a school or other educational setting.

For you to talk about“You are a teacher of small children and you want to improve your teaching of number. What do you do?” |

||||||||

Reflection on the activity None of these examples are action research as such but the exercise may highlight some of your assumptions about what counts as useful knowledge in teaching. Naturally much depends on context: for example if you do not teach young children, and know little about teaching number, you may rely more on the literature and the advice of experienced colleagues; in contrast you may have taught number to young children for years using many different approaches and wish to get a handle on what works best and why; or you may have thought or heard of some new approach that you wish to assess the value of. Nonetheless this exercise raises the question: do you learn by doing? ...by reflecting? ...by reading? ...by talking to others? Action research involves all of these methods. |

| Action research can lead to curriculum renewal built around the needs and interests of practitioners. This is an important consideration at a time when there is increasing concern over the top-down nature of school reform. Yet the literature and our own day-to-day experience tell us that the reforms which work best are the ones which we as teachers have identified as relevant. This is to be expected as people are generally more motivated and enthusiastic about changes if they think these changes have a genuine potential for improvement. |  |

Action research can lead to extended professionalism and reflective teaching. Is a reflective teacher a ‘better’ teacher? …perhaps we will never know for sure, but the teacher who thinks about her practice in a systematic way is more likely to be aware of a wider repertoire of approaches. As such she is more able to detect, respond and adjust to the shifting demands and interests of pupils.

Action research is based on educational principles. That is to say it brings to the fore the fact that we as teachers are learners. In this sense we can share the joys and frustrations of the learning process that our pupils experience. This leads to not just a more effective role for the teacher but, hopefully, a more satisfying one too.

Tensions within Action Research

| The tensions that exist within action research were hinted at above in the section ‘ What is action research?’. These tensions may lie in gulf between bottom-up changes, which originate at the classroom and school level, and top-down changes, which originate at the government or local authority level. While the former are arguably more responsive to the demands upon learners and practitioners within a school setting, the latter are arguably more generalised and efficient to implement. |  |

A seminal work by Carr et al (1986) (6) recognised the need for a more radical research agenda, arguing that through action research practitioners can identify, understand and, ideally, overcome any barriers to rational change. However over time action research has become 'safe'. For example, the Department for Education and Skills sees action research as a means for teachers to implement the department's reform agenda in a more sensitive and responsive manner. It is unlikely that the department would be so sympathetic to Carr's original agenda.

sees action research as a means for teachers to implement the department's reform agenda in a more sensitive and responsive manner. It is unlikely that the department would be so sympathetic to Carr's original agenda.

What is wrong with Action Research?

(Popkewitz, 1984) (7)

One criticism leveled at action research is that it is based on local innovations that are context and setting dependent and therefore not generalisable. For example the Becta Test Beds site looks at many instances of using ICT in schools but it is difficult for the policy maker to draw conclusions from this (8). Other criticisms are leveled at the practitioners themselves, pointing out that teachers may well lack the time to carry out such research and do not want to play the role of researcher. This leads some commentators to question the rigour of action research for example the size of the samples used in evaluation; the lack of triangulation in some studies; and lack of distance between teachers and key respondents such as pupils and colleagues. There are also complaints that action research is often poorly reported and overly descriptive. looks at many instances of using ICT in schools but it is difficult for the policy maker to draw conclusions from this (8). Other criticisms are leveled at the practitioners themselves, pointing out that teachers may well lack the time to carry out such research and do not want to play the role of researcher. This leads some commentators to question the rigour of action research for example the size of the samples used in evaluation; the lack of triangulation in some studies; and lack of distance between teachers and key respondents such as pupils and colleagues. There are also complaints that action research is often poorly reported and overly descriptive. |

|

Case Study“Test Beds project  ” ” |

||||

Some examples of action research studies are available at http://www.evaluation.icttestbed.org.uk/research. Read one of the studies and assess its value from point of view of:

|

Who will Action Research appeal to?

The appeal of action research to a practitioner may depend on his or her particular learning style (9). For example it may appeal as much to ‘doers’ as ‘reflectors’, that is it is a form of academic enquiry which might appeal to those with a practical rather than analytical bent. In addition action research may appeal to teachers with a particular view of knowledge as contextual and learning as structured by setting (10). In this view teachers are considered to have useful knowledge that derives from the meanings they make within their working environment. These teachers will be suspicious when they are told that there is clearly identifiable good practice to hand down.

For you to talk about“What philosophical position helps a teacher get the most out of action research?” |

|

| Considerations: Action research is not in the business of stating that teachers or agencies know best. Good and bad ideas may come from both. Our purpose in action research is to test what we know within the freedoms and constraints of our work environment. The hope is that ideas are empirically investigated and shaped by practitioners. Action research may appeal to teachers seeking more autonomy in their teaching while being welcome to support, advice and support and willing to justify the steps they are taking. |

Teachers should be at the centre of research:

“ [Teachers know] that ideas and people are not of much real use until they are digested to the point where they are subject to the teacher’s own judgement. In short, it is the task of all educationalists outside the classroom to serve the teachers; for only teachers are in the position to create good teaching”

(Stenhouse, 1984) (1)

What is difficult about Action Research?

As discussed above in the section ‘ What is wrong with action research?’ many common-sense ideas from conventional research are rejected. This means that the practitioner-researcher has to create his or her enquiry from scratch making it difficult to get a handle on what to do. Additionally, action research is challenging as the practitioner is responsible not just for generating data and conclusions but implementing changes too. Activities such as a literature review can be more demanding because precisely which literature will be of relevance is not known from the outset. Typically lot of time is spent on identification of a problem - action research is time consuming and ‘messy’. Conventional formats for writing up research are unlikely to be appropriate again making it challenging.

For you to talk about“You are teaching a class of 30 secondary children about volcanoes. Not of all them seem interested and this is a problem!” |

||||

Reflection on this activity This example is deliberately broad and is intended to provoke the range of responses that we all experience when facing problems in our practice. For example some may see this as a problem of text-based resources failing to capture the exciting and violently dynamic nature of volcanoes as well as multimedia resources might. Others may be concerned that the topic is remote from their pupils’ experiences and ask “Why should they be interested in this?” This may lead to finding out whether pupils do in fact have any personal experiences of volcanoes (perhaps some have visited the Canary Islands on a family holiday). Others still may see this problem as due to dull didactic teaching or other ‘failing’ technique. Perhaps the difficulty is a cultural problem such as a number of pupils in the class unable to focus attention for sustained periods when requested to sit still and listen. A potential point of reference would be to ask the pupils explicitly about this - but what might be the constraints and limitations of this approach as a guide to action? |

For you to talk about“Sum up what you think the strengths and difficulties might be in action research. The following table might provide a focus for your ideas.” |

||||

|

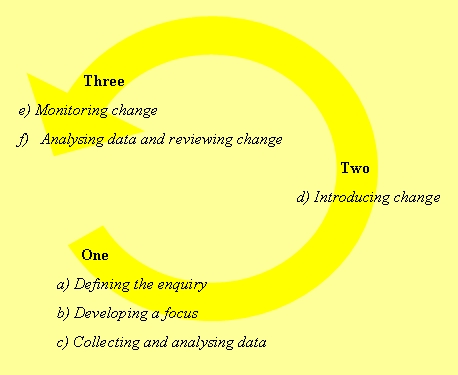

Steps in action research

(1) What is the problem(2) Reconnaissance

(3) Focus

(1) What is the problem

How do you know there is a problem?

Your motivation to address this problem may arise from...

| ...a process of reflection. | For example comparing your practice to a new approach explained at a training event, or considering feedback on an observation of your lesson or a discussion with colleagues. This has led you to believe you are not doing something which has the potential to develop your repertoire as a teacher. |

| ...the feedback of pupils. | For example you sense pupils are switched off or are not achieving what you thought they would. |

| ...being imposed upon you. | For example senior management wanting to push through programme of change about which you feel ambivalent. Perhaps you have been offered feedback which appears contradictory and even counter intuitive. |

Key questions for the action researcher are: (i) What is the nature of the problem? (ii) Whose problem is it? (iii) What has led to your awareness of the problem?

For you to talk aboutUse the following quotes to help you think about these questions: |

||||||||||||

|

For you to talk aboutThink about the problems you have in your practice. What is causing you most concern? This is not necessarily that which is causing grief but might be an awareness that could be much better, or a feeling that you have become 'stale'. Consider if these problems are: |

||||||||||

|

(2) Reconnaissance

Your first attempts to get to grips with the problem you have chosen to tackle are sometimes described as reconnaissance. Here you might want to explore other perceptions of the problem. For example, it concerns you but do colleagues and pupils see it in the same way?

At this stage you might 'test the water' with...

- ...small informal discussions.

- ...reflection on reading.

- ...reflection on courses you have attended in the past.

- ...exploration of data on attendance and achievement.

- ...other approaches.

(3) Focus

It is important you chose an issue which is important to you - and that you do not tackle something you cannot change. An action research enquiry needs to be driven by a clearly stated problem but this requires much time spent in refining the problem. For example, the research undertaken should be small scale but problem statements usually start out large and unmanageable such as...

"How can I motivate my classes better?"

" How can I introduce better assessment approaches?"

| Not only are these big questions but they do not lead to a focused solution for addressing the problem. You may find yourself committed quite early on to one approach but a good exercise is to brainstorm different possible approaches to the problem and seek out evidence in support of those solutions. This evidence will involve you in a good deal of introspection, but as well it is important to work collaboratively where possible and ascertain the views of others. |  |

"What do colleagues have to say on the nature of the problem?" (Particularly if these same colleagues are the ones proposing change in your practice)

"What does the wider literature tell you?"

Almost certainly you will want to get pupil feedback before becoming committed to a solution. Pupils cannot provide you with an infallible guide as to what to do but they can help you predict what seems feasible and appropriate in contemplating change.

Having identified possible solutions you will be in a position to ask much more specific questions in your research. For example…

"Will opportunities for group work in a Y7 class lead to more on task behaviour?"

"Will peer assessment enable pupils in Y10 to understand externally imposed assessment criteria?"

You should also link your enquiry to teaching and learning and, where possible, school development plans and other priorities.

For you to doHave a go at developing a tightly focused research question. You need to ask your self: |

||||||||

|

For you to talk aboutRead the case studies below (12) and comment on the issues. |

||||

|

For you to doAre there new approaches to teaching which you have seen or read about that appeal to you? Investigate these approaches further and develop innovations, small steps at first, in your teaching. Seek feedback form pupils and colleagues and consider ways of taking these innovations forward. |

Final Thought

Action research can break this divide!!

Notes

- Stenhouse, L. (1984) Artistry and teaching: the teacher as focus of research and development In: D. Hoskins & M. Wideen (Eds.), Alternative perspectives on school improvement, London: The Falmer Press.

- Cited from Lewin, K.(1948) Resolving social conflicts, New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Corey, S. M. (1953) Action research to improve school practices, New York: Columbia.

- See for example the DfES action research project Schools Facing Exceptionally Challenging Circumstances last accessed 27.12.05 at http://www.standards.dfes.gov.uk/sie/si/SfCC/in/octet/

- Cited from the page How is Action Research Defined? by South Florida Center for Educational Leaders, College of Education, Florida Atlantic University last accessed 27.12.05 at http://www.coe.fau.edu/sfcel/define.htm

- Carr, W. and Kemmis, S. (1986) Becoming Critical. Education, knowledge and action research Lewes: Falmer.

- Popkewitz, T. S. (1984) Paradigm and ideology in educational research: The social functions of the intellectual. New York: Falmer.

- See Pittars, V. (2004) Evidence for E-learning Policy, Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 13(2)

- For more on learning styles download the documents on the Pedagogy and Practice page of this website.

- For example see Lave, J. (1988) Cognition in practice: mind, mathematics and culture in everyday life, Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, Cambridge.

- Robson, C. (1997) Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-researchers (Regional Surveys of the World) Blackwell Publishers.

- from Hammond, M. (2005) Next steps in teaching. London: Roultedge.

- Gore, J. and Gitlin, A. (2004) [RE]Visioning the academic-teacher divide: power and knowledge in the educational community, Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 10(1), pp.35-58

Page Content

What is Action Research?

Why Action Research?

Tensions within Action Research

What is wrong with Action Research?

Who will Action Research appeal to?

What is difficult about Action Research?

Steps in action Research:

(1) What is the problem?

(2) Reconnaissance

(3) Focus

Final Thought

Notes