Secondary School Characteristics and University Participation

Secondary School Characteristics and University Participation

Friday 6 Jun 2014How well students perform in their GCSEs plays a pivotal role in whether they go to university and how well they do once they are there, research by Warwick’s Claire Crawford finds.

Secondary schools can boost university participation and performance by helping students to make the right choices about the subjects and qualifications they take, and to achieve good grades at GCSE level, new Warwick research shows.

In addition, the research finds that students from less effective state schools who do reach university outperform students with similar qualifications who attended more effective state schools, selective schools or independent schools - a finding that suggests that universities may wish to consider pupils’ backgrounds, including the schools they attend, when making admissions offers.

The findings stem from research conducted by Claire Crawford, assistant professor in the Department of Economics at the University and a research fellow at the Institute for Fiscal Studies. In work undertaken for the UK Department of Education, she analysed how higher education (HE) participation and outcomes differed by secondary school characteristics, and what factors help to explain these differences.

At university, students from less effective state schools outperform students with the same qualifications who come from more private, selective or more effective state schools.

“These results highlight the importance of ensuring that pupils from all schools make the right choices over the subjects and qualifications they take at GCSE, and that they maximise their chances of getting good grades at this level, as these results play an important role in explaining who goes to university and how well they do once there,” Crawford said. “They also provide some evidence that, amongst students from similar backgrounds with similar GCSE and A-level results, those from less effective state schools may, on average, have higher ‘potential’ than those from private, selective or more effective state schools. Whilst recognising that this is a result that holds on average and of course not for every student, this is something which universities may want to take into account in making entry offers.”

Overall, students who attend more effective state schools, selective schools and independent schools, are more likely to go to university, especially high-status universities (those in the Russell Group, plus those with similarly high research quality) than students who attend less effective state schools; they also have higher graduation rates and are more likely to be awarded a higher degree class once there, the research shows. But the fact that different types of students attend different types of schools plays an important role in understanding these differences, she found.

When students with similar backgrounds and qualifications are compared, the differences in terms of who continues into higher education disappear. Moreover, the differences in terms of drop-out, degree completion and degree class actually reverse: students from less effective secondary schools who make it to university are far less likely to drop out, and far more likely to graduate and to attain a first or a 2:1 than students with similar characteristics and similar grades from more effective secondary schools.

The findings suggest that students from these less effective schools could be regarded as having higher “potential” than students with similar characteristics and GCSE and A-level results who come from more effective schools.

The research analysed the relationship between university participation and outcomes and a variety of secondary school characteristics – including school type and selectivity, whether the school has an attached sixth form; the proportion of pupils eligible for free school meals, the average value added by the school between Key Stages 2 (age 11) and 4 (age 16), and the proportion of students who obtain at least five GCSEs at grades A*-C.

GCSE subjects, qualifications and grades matter for university participation decisions and performance.

The comparison of like-for-like peers took into account characteristics including gender, ethnicity, month of birth and eligibility for free school meals (a proxy for low family income), as well as a rich set of achievement measures, including scores at Key Stage 2; and the qualifications, subjects and grades that students achieved at Key Stages 4 and 5.

Crawford analysed data from records of secondary school students in England to see whether and where they attended university, whether they dropped out within two years, whether they completed their degree within five years, and whether they graduated with a first or a 2.1.

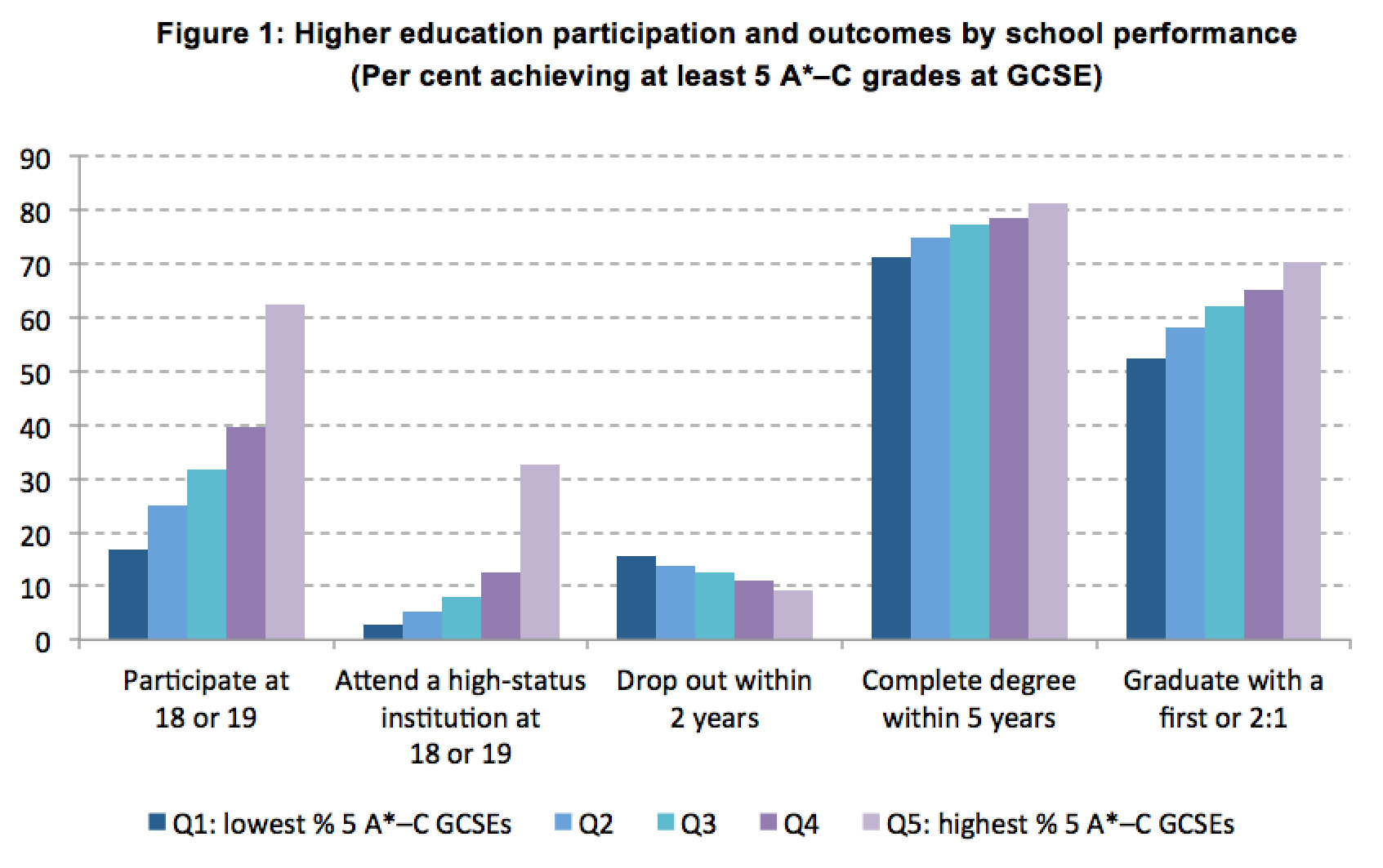

A student’s likelihood of going to university varies substantially depending on the characteristics of his or her school. For example, Figure 1 shows that 62 per cent of pupils who attend schools with the highest proportions of pupils achieving 5 A*-C grades at GCSE go to university at age 18 or 19, compared to just 17 per cent of those in the bottom fifth of schools as rated by GCSE performance. The differences are even starker for students attending high-status universities. Students who attend secondary schools in this upper tier (the top fifth of schools as measured by GCSE results), are 11 times more likely to attend high-status universities than pupils whose scores are in the bottom tier (the lowest fifth of schools as measured by GCSE results).

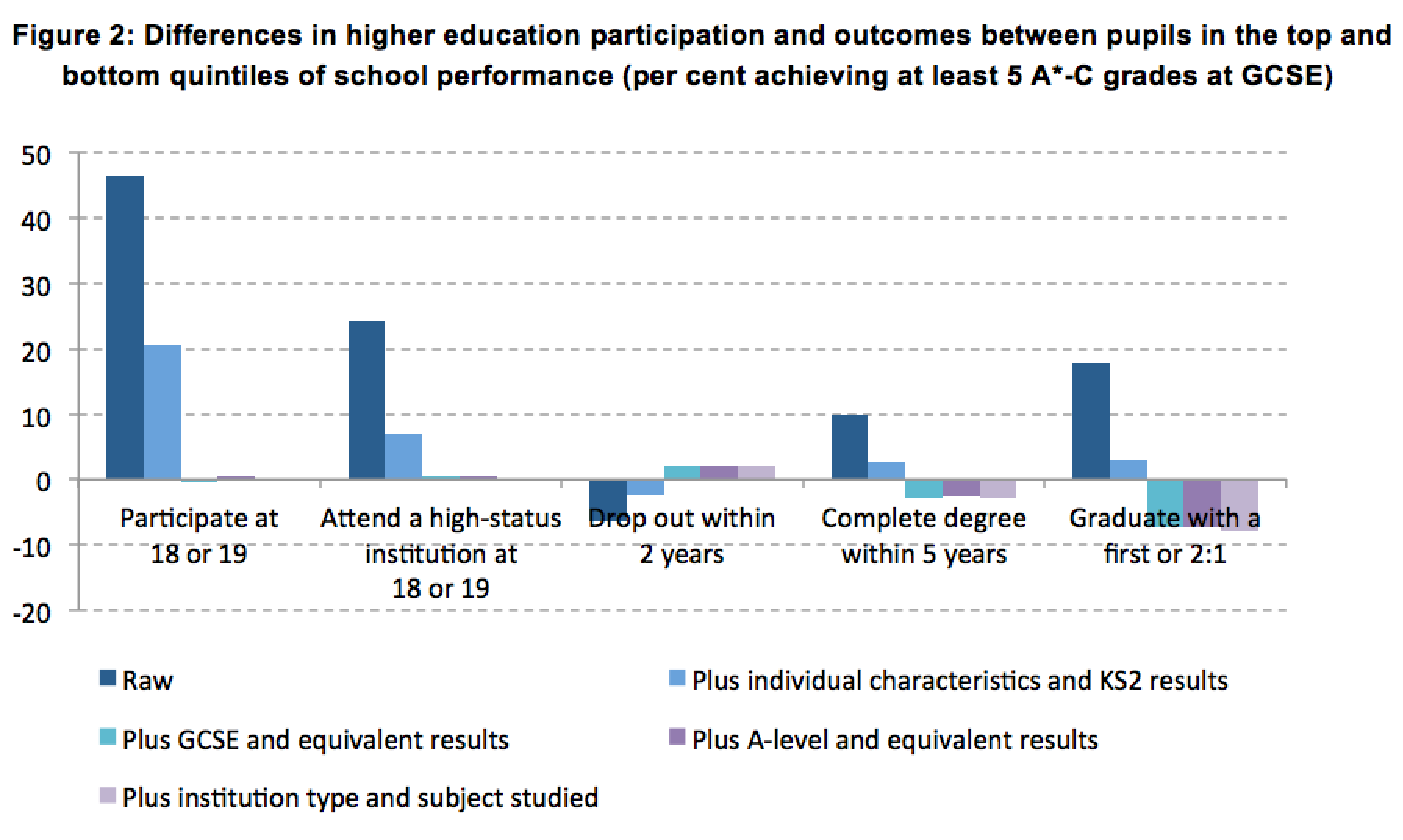

Figure 2 shows what factors help to explain these differences in participation rates. The fact that different types of pupils go to different types of schools is important: accounting for the attainment of pupils on entry to secondary school (in Key Stage 2), as well as a limited set of background characteristics, explains well over half of the difference in participation rates between pupils who attend low- and high-performing schools.

Once measures of attainment at the end of secondary school (in the third set of bars) are accounted for, the remaining differences all but vanish. This suggests that taking pupils’ background characteristics and their attainment at the end of secondary school into consideration explains virtually all of the difference in participation rates between pupils attending different types of schools.

The research also found an association between the characteristics of students’ secondary schools and the outcomes of students who do attend university. Pupils who went to the highest-performing secondary schools were nearly 7 percentage points less likely to drop out within two years, just over 10 percentage points more likely to complete their degree within five years and nearly 18 percentage points more likely to graduate with a first or a 2.1 than pupils who went to the lowest-performing secondary schools. However, once account is taken of the differences in pupils’ characteristics and performance prior to going to university, the outcomes reverse: pupils from high-performing schools are now more likely to drop out, less likely to complete their degree and less likely to be awarded a first or a 2:1 than similar pupils with similar attainment from low-performing schools. This remains true if pupils from different schools who attend the same universities and study the same subjects are compared.

The full report is available on the Department for Education website.