10 March 2016: Findings on Family Reunification

by Dr Vicki Squire and Nina Perkowski

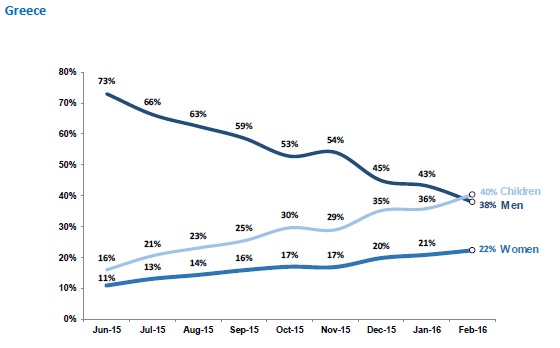

In February 2016, UNICEF reported that women and children made up 60% of those seeking to cross the border between Greece and FYROM, whereas in June 2015, 73% of arrivals in Greece had been adult men. As the UNHCR graph below show, there has been a steady increase of women and children over the winter months, which is also the most dangerous time to cross the sea.

Graph: UNHCR, 2016

Médecins du Monde warned already last August that women and children also increasingly ended up in camps in Calais, without adequate reception provisions being made available for them. The sharp increase of women and children along the eastern route and in Calais indicates that the limited availability of family reunification routes and associated long waiting periods may encourage vulnerable groups to undertake dangerous journeys. Results from our first research phase demonstrate the importance of family reunification for many interviewees, although this differs across our research sites.

We have compiled a detailed overview document showing the proportions of people who sought to join family in the EU, who had friends in EU countries, or who had left close family members behind in transit or origin countries. The document summarises our findings in Sicily (Italy) and Kos (Greece), where a total of 101 in-depth, qualitative interviews were conducted between September and November 2015. This blog post seeks to set some of these findings into a wider context.

In our research sample, 51% of interviewees in Kos had family members in EU member states, whom they often sought to join. 10% of interviewees in Kos sought to move to EU countries in the hope of allowing relatives to follow them through family reunification mechanisms. This included frail elderly parents, pregnant wives, or young children, for whom the journey was deemed too risky. Beyond family networks, many interviewees in Kos also had friends who had moved to the EU, whom they often sought to reach.

In Sicily, the situation was different. Indeed, 52% of interviewees explicitly stated that they had not known anybody in the EU prior to arriving in Sicily, and only 14% had family members in an EU country. There is a marked differentiation in Sicily, with some arrivals moving through the island much more quickly than others. It is likely that those with a clear migration strategy and family members within the EU form part of this group, and are thus less likely to be captured in our research sample

While most of those we interviewed fled insecurity and conflict in their home countries, and thus did not leave these countries in order to reunite with family, many of those who arrived in Kos tried to reach countries where they already had family members. At the same time, however, many were also aware that family reunification was often a lengthy and complicated process. When asked what they would tell policymakers if they could, one interviewee said: “I would say to proceed quickly the family unifications because it takes a lot of time. I had to bring my wife and my children with me, to put them in danger, and my brother the same, with 3 children.”

Several interviewees shared similar stories, explaining that whole families had made the dangerous crossing of the Aegean Sea because family reunification was not a realistic option given its often narrow scope and slow progress. Their stories might explain why there has been a stark increase of women and children arriving in Greece over recent months.

Together with our wider research findings, their stories also illustrate the need for fundamental changes in EU policies. Rather than further restricting family migration and relying on deterrence, our recent evidence brief puts forward the following suggestions:

- Replace deterrent border control policies with interventions that address the diverse causes of irregular migration

- Revise migration and protection categories to reflect the multiple reasons that people are on the move

- Open safe and legal routes for migration, and improve reception conditions and facilities

- Improve rights-oriented information campaigns across neighbouring, transit and arrival regions

Instead of further exacerbating the vulnerabilities of people on the move, these suggestions would allow both individuals and families safe access to protection in the EU.