A Family Affair

Claire Sewell

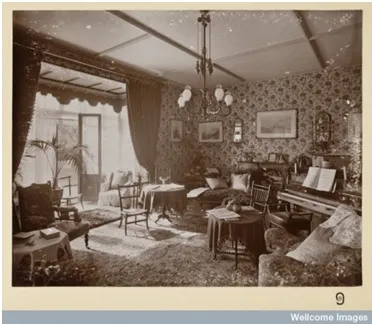

The Drawing Room at Ticehurst Asylum

Private asylums favouring techniques of humane moral management to cure their patients over the use of chains and manacles to restrain them, such as the York Retreat, were designed to recreate domestic environments and to have a similar structure to the family home. Many private asylums, including Thomas Bakewell's Spring Vale, were run as family businesses. The family was also envisaged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries - as in more recent times - as both a potential cause of insanity and a possible aid to cure.

Some doctors believed that the stresses of family life were responsible for the onset of insanity. This was often gendered, with instances of women suffering from 'insanity of childbirth' which could be triggered by unhappy domestic circumstances and men being deemed insane for unsatisfactorily fulfilling their duties as the patriarchal head of the household. Towards the end of the eighteenth century increasing optimism about the potential curability of insanity also led to arguments for institutional as opposed to familial care and families were urged to release their sick relatives as soon as possible to the care of specialised asylums. However, some mad-doctors, raised concerns about the need to scrutinise familial accounts of their relatives’ insanity to counter the risk of wrongful confinement. These concerns were satirised in the eighteenth century in the following pamphlet extract:

Several are put into Mad-Houses, as they are called, without being mad. Wives put their Husbands in them that they may enjoy their Gallants, and live without the Observation and Interruption of their Husbands; and Husbands put their Wives in them, that they may enjoy their Whores, without Desturbance [sic] from their Wives; Children put their Parents in them, that they may enjoy their Estates before their time; Relations put their Kindred in them for wicked Purposes. (Anonymous, Proposals for Redressing Some Grievances Which Greatly Affect the Whole Nation (London: J. Johnson, 1740).)

However, as historian Akihito Suzuki has argued, families were also seen as playing a key role in the diagnosis, treatment and management of their relative's mental illness both inside the home and in the asylum, especially those able to pay for the services of mad-doctors. Families' decisions were based on both emotional and financial concerns. Before admission to private madhouses, family members were often asked to describe the nature of their relative’s insanity, giving them the scope to influence the diagnosis and decision to admit the patient. Many of these familial accounts of their relative’s illness tend to demonstrate that the family could no longer manage insanity within the home. For instance, in July 1848, Elizabeth Winser was committed to Ticehurst asylum with a 'general dislike of friends, declination to take food, & a constant desire to leave her house & wonder about & wish to see her brothers & others who have been dead a long time'. Another trigger for admission was violent behaviour: in 1856, Arthur Basset was committed to the same asylum after becoming violent, suicidal and 'wildly incoherent in his manner & conversation… often howling and screaming'. Despite, psychiatrist John Conolly's concern to scrutinise family testimony to counter the risk of wrongful confinement, his comments proved unpopular, demonstrating the significance of families' accounts at the time of confinement.

Many families dreaded the stigma of insanity and the asylum, and would look after their relative at home for as long as they could manage before seeking outside help. Interestingly, the theme of stigma can be found in literary fiction of the time, most famously the motif of the mad woman in the attic, for example, in Charlotte Brontё's 'Jane Eyre'. However, in reality relatives were not always simply locked away in institutions. 'Domestic psychiatry' is used to refer to the families who managed and provided some form of treatment for their insane relatives in the home. In some instances, patients were taken out of asylums by their relatives without being cured, with family members opting to provide care in the home. Romantic poet, Robert Southey's, wife Edith was released 'as admitted' from the York Retreat after a year's stay to be cared for at home by Robert and their daughters. Robert could not bear to leave Edith in an asylum, even one with such a sought after reputation as the Retreat.

Further Reading:

• Mary Elizabeth Braddon, Lady Audley's Secret (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

• Charlotte Brontё, Jane Eyre (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997).

• Charlotte MacKenzie, Psychiatry for the Rich: A History of Ticehurst Private Asylum, 1792-1917 (London: Routledge, 1992).

• Hilary Marland, Dangerous Motherhood: Insanity and Childbirth in Victorian Britain (Houndmills: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2004).

• Roy Porter, Mind-Forg’d Manacles: A History of Madness in England from the Restoration to the Regency (London: Athlone, 1987; Penguin edn, 1990).

• Leonard Smith, 'To Cure those Afflicted with the Disease of Insanity: Thomas Bakewell and Spring Vale Asylum', History of Psychiatry, 4 (1993), pp.107-127.

• Akihito Suzuki, Madness at Home: The Psychiatrist, the Patient, and the Family in England, 1820-1860 (Berkeley: California University Press, 2006).