DNA at Britain's Borders

Research conducted by Professor Roberta Bivins

Once upon a time, a long, long time ago, I was a biologist working in laboratories where scientists did work ranging from studies of the sexual dimorphism of the brain (in frogs, mind you, not people!) to the factors that could stimulate nerve growth (in mice this time). I paid my way through postgraduate studies by working on the Human Genome Project – and indeed, I got the T-shirt, literally, when the lab I worked in completed a key preliminary step in that massive project by fully sequencing the genome of a mammal (a mouse again: in fact I know a surprising amount about mice, as well as a particular amphibian, called Xenopus laevis).

Perhaps my current interest in the uses of DNA is because of this early exposure. Then again, perhaps it is because of the ways in which genetics and genomics have become so highly visible and influential in how we think about ourselves, our individual and social pasts, and our futures. In any case, alongside my work on immigration and the National Health Service, I have begun a project exploring DNA at Britain’s borders. Surprisingly, the UK’s early move towards using genetic information to manage migration has been little explored. However, my research suggests two really important impacts of that work.

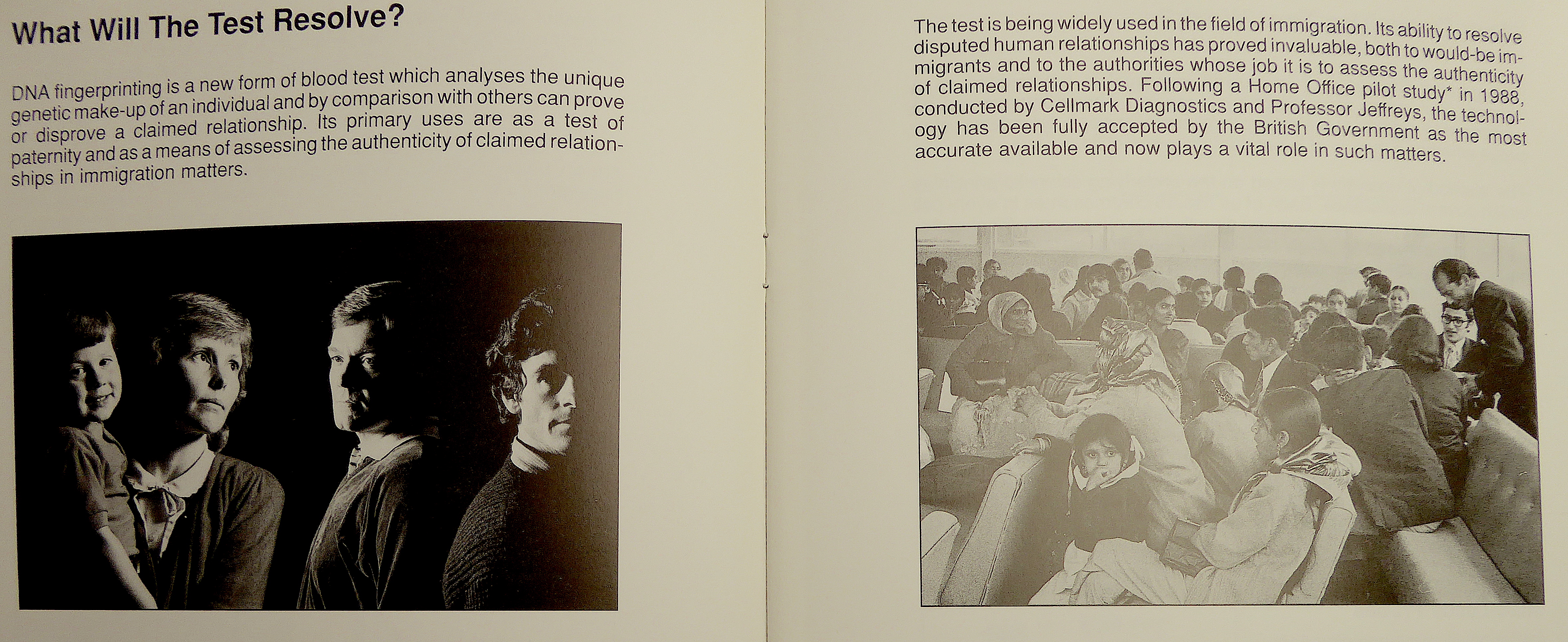

First, as I have written here, I have uncovered really vital and important connections between empire, post-empire and activist Asian and British Asian migrants and their allies and the development of the technology we now know as ‘genetic profiling’. This technology has become familiar to us through television shows ranging from the US CSI franchise to the popular family history show ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’. But it began as a tool that helped Asian migrants to Britain reunite with their families despite government resistance and the original ‘hostile environment’.

Second, I argue here that this development – one in which DNA unexpectedly overturned state claims that a significant proportion of migrants were ‘bogus’ – also helped to shape our attitudes towards DNA profiling more widely. They also supported its commercial development, offering a new model of the ways in which ethnic minority populations power innovation in medicine and biotechnology.

I am continuing to research these and other questions around the emergence of DNA as a ’truth machine’, as well as the ways in which looking for medical and identity ‘truths’ exclusively in the body, rather than in cooperation with people and communities can be dangerous and can reinforce – and perhaps even generate health inequalities.