Mary Toft's First Confession

Published June 2022, Prof Karen Harvey, University of Birmingham

In 2012 I was preparing to teach a module on the case of Mary Toft who alleged to have given birth to rabbits in 1726. The module was intended to teach second-year students about source analysis through a discrete and manageable case study. The case caused a media sensation and I knew well many of the primary sources associated, notably the well-known printed pamphlets and engravings. These sources had shaped the studies of the case which focussed on either medical historical perspectives or broader concepts relating to the imagination and the self. In their often satiric reinvention and representation of the case, these printed sources underscored that the case was a hoax.

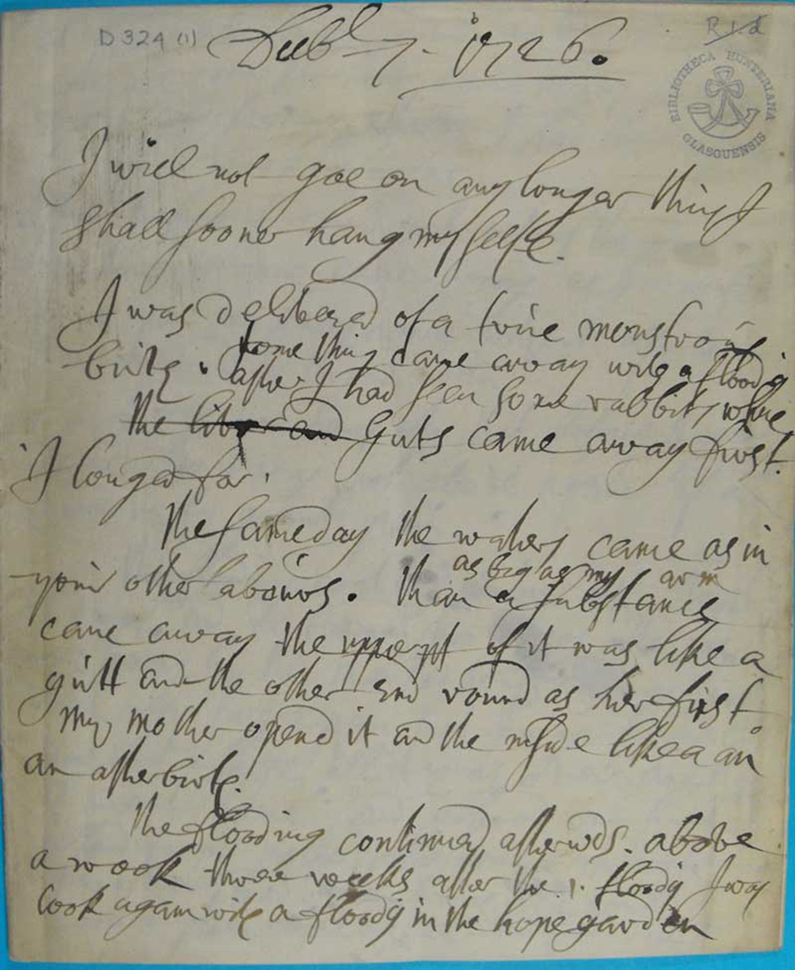

Mary Toft’s three ‘confessions’ were new to me. These were taken down by James Douglas, a doctor present on these three occasions that Toft was questioned by a Justice of the Peace. There were passing references to them in at least two works that referred to the case, those by Dennis Todd and Lisa Forman Cody.[1] I was intrigued and also knew that they would add another source type to the module, enabling my second-year students the chance to consider manuscript material. Unable to travel to Glasgow immediately, I was delighted that Glasgow University Special Collections offered not only to send me digital photographs of the confessions but to make these available to my students via their Flickr site.

Reading these thirty-six pages was an absolute revelation. The writing jumped off the screen. In their form and their content, they were urgent, vivid and disturbing. They recorded Toft’s version of events in what appeared to be as close to a transcription as Douglas could possibly muster. They were also far richer than I had imagined from the fairly cursory discussions in existing scholarship. But it also became immediately apparent why historians had not undertaken a thoroughgoing analysis of the confessions and placed this centre-stage in their accounts of the case. Not only were these extremely messy as documents – full of errors and deletions – but the narratives they offered were inconsistent and contradictory. These errors and deletions, I suspected, offered one key to unlocking the case.

These documents seemed to offer the opportunity to put Mary Toft herself at the heart of an account of the rabbit-births. I was on the train to Glasgow within months and began to work on the confessions in earnest. First, I transcribed them, ensuring that I recorded the irregularity in the manuscripts themselves as best I could.[2] Then I began to order my notes into topics (such as ‘neighbours’, ‘clothing’ and ‘pain’). I compared the three different versions that Toft provided during each episode of questioning, developing a careful record of how her story changed. The disparities would underpin an important component of the account of the different voices in the case in my subsequent History Workshop Journal article and the book, The Imposteress Rabbit Breeder. I argued that the inconsistencies that had caused other historians to sideline the confessions could actually be one route back to Mary Toft’s own embodied experience of the hoax.

‘Hoax’? That word might imply that the rabbits births were fictitious, unreal, imagined. A woman gestating rabbits was impossible. But ultimately the confessions bring Toft’s voice to the forefront. In doing so, they impress upon us what a physically and emotionally distressing process giving birth to rabbits really was.

[1] Lisa Cody, ‘“The doctor's in labour, or, A new whim wham from Guildford”’, Gender and History, 4 (1992), pp. 172–96; Lisa Forman Cody, Birthing the nation: sex, science, and the conception of eighteenth-century Britons (Oxford University Press, 2005); Dennis Todd, Imagining Monsters: Miscreations of the Self in Eighteenth-Century England (University of Chicago Press, 1995).

[2] Dennis Todd’s transcriptions, which he has generously made public, differ from my own and largely leave out the irregularities and Douglas’ symbols. See https://tofts3confessions.wordpress.com/.