Global History and Latin America: A Historiography under Development

Published: 9 March 2022 - Camilo Uribe Botta

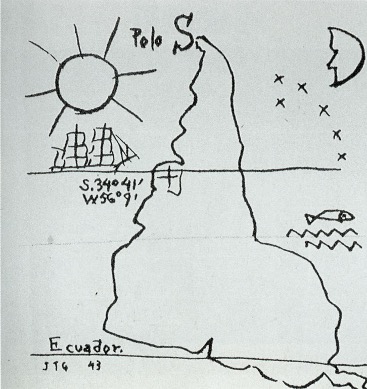

Latin America is a region that has been at the core of global processes since the European invasion of the continent in the 16th century. From the early stages of the conquest by the Spanish and Portuguese, to the Columbian exchange that followed, the trans-Atlantic slave trade involving also the British, Dutch and French empires, the age of revolutions in the 19th century and the Cold War tensions in the 20th century, Latin America is a complex territory with a rich global history. As recent scholarship has argued, taking Latin American history seriously as a core component of global history carries ample potential to reorient our perspectives (Figure 1).

Figure 1. América Invertida, Joaquín Torres García, 1943 (Museo Juan Manuel Blanes, Montevideo).

The constant movement of people, ideas and objects has long been part of Latin American history. But ironically, Latin America has barely been part of the Global History historiography in the last twenty years. Very few global historians are working on this region and in Latin America itself the discipline has not been well established in the region’s different historiographic traditions. Based on two articles published by Matthew Brown[1] in 2015 and by Sven Schuster and Gabriela de Grecco Lima[2] in 2020, the purpose of this blog is to examine how Global History is perceived in Latin America and why it has not had the visibility it enjoys in other parts of the world, mainly in Europe, North America, and Asia. This discussion also takes into account some points raised in a discussion that took place in the Global History and Culture Centre (GHCC) Reading Group held on 9 February 2022 at the University of Warwick.

From my personal experience as a historian formed in Latin America, Global History as a trend is almost non-existent in the region’s history departments. Only in the last five years have a few historians trained in Europe started to engage with Global History, in the context of a historiographical tradition that tends to create a strong division between historia nacional (national history) and historia universal (universal history), as Matthew Brown clearly explains in his paper. But there also exists a gap in a methodological and conceptual sense: Global History categories may sometimes not be ideal for reconstructing the historical realities of Latin America from a Global History perspective.

Global History emerged as a historiographical approach that, among other things, wanted to overcome notions deeply embedded in European historiography: the concept of the nation state and Eurocentrism. The debate about these key concepts in Global History is one of the reasons why in Latin America there is some scepticism. For example, as regards Eurocentrism, where do we locate Latin America in the South/North or West/Rest divisions of the world? In a region that crystallised following the decline of the Spanish and Portuguese Empires 200 years ago, its integration into (or isolation from) the rest of the world may not fit that dichotomy. A tendency to equate globalization with westernization is erroneous and the challenge to see a global world from a non-Eurocentric perspective remains. As colleagues noted in the reading group, there are many South-South academic links between Global South academics that for example have made important contributions to the successful spread of subaltern studies from South Asia to Latin America before entering the North American and other academic schools.

Schuster and De Lima Grecco state that, in Latin America, Global History is considered a Eurocentric Anglo-American trend that does not adapt well to national research agendas in Latin America. As an Anglo-Saxon trend, it is strongly connected with language. Most of the Global History historiography has been produced in English and it is difficult to find great Global History works translated into Spanish or Portuguese. In Latin America there is still a strong language barrier where most of the historiographical production is in Spanish or Portuguese. Even if English is becoming the lingua franca in academia, it still has a weak presence among many areas of Latin American historiography, a trend that is only slowly changing with some great works about Latin America now being published in English even before they appear in Spanish.

But language, more than a barrier, could also be an advantage. Knowledge of Spanish, Portuguese, and indigenous languages such as Quechua or Aymara by many Latin American historians could lead to new methodologies and ways to read the colonial and national archives, full of sources that are fundamental to understanding the global history of the region. More than anything else, this is an invitation to engage in multilingual approaches to Global History in Latin America.

Another category that Global History analysis seeks to overcome that remains central in Latin American historiography are borders, which are a key concept to understanding the formation of national states that share a colonial past with a strong process of mestizaje. A Latin American national history with a global approach could be a new and fascinating way to understand where Latin American countries stood in the global context after the nineteenth-century wars of independence and their role in a modern and contemporary world.

This is an invitation also to think about Global History from Latin America, to understand a region characterized by a complex history with formal (Spanish and Portuguese) and informal (British and United States) imperialism, unequal relationships of trade, knowledge, and movement of people, or even sometimes no movement at all. It is fundamental to overcome Eurocentrism and to achieve a Global History from the South, where very interesting disciplines and concepts have been at the centre of the social, political, and cultural discussions in the last decades, such as decolonial and subaltern studies. Following Mary Louise Pratt’s concept of “contact zone”[3], a Global History in Latin America may show many complex aspects of the region, from being at the core of imperialism, to being an agent of globalization, and its central or peripherical role on many global processes.

Figure 2. The Man Behind The Egg. Political Cartoon published in the Sunday Times, New York, 1903.

There is a long and complex history about the American Empire and Latin America, that goes back to the nineteenth century. Spanish, Portuguese, British, and American imperialisms have been part of the region’s history. A great example of this process of appropriation, subordination, and exploitation was the independence of Panama and the construction of the Panama Canal, as North American cartoons showed at the early 20th century. For example, in Colombian historiography this process is seen through a very national approach as a consequence of the One Thousand Days Civil War (1899-1902), whereas a global approach could elucidate the power dynamics behind Panama’s independence in 1903 (figure 2). Also, American Imperialism could be a topic that could help to integrate Latin America and Caribbean history, two very closely related regions that ironically remain as two different entities for historiography, as some colleagues noted in the discussion.

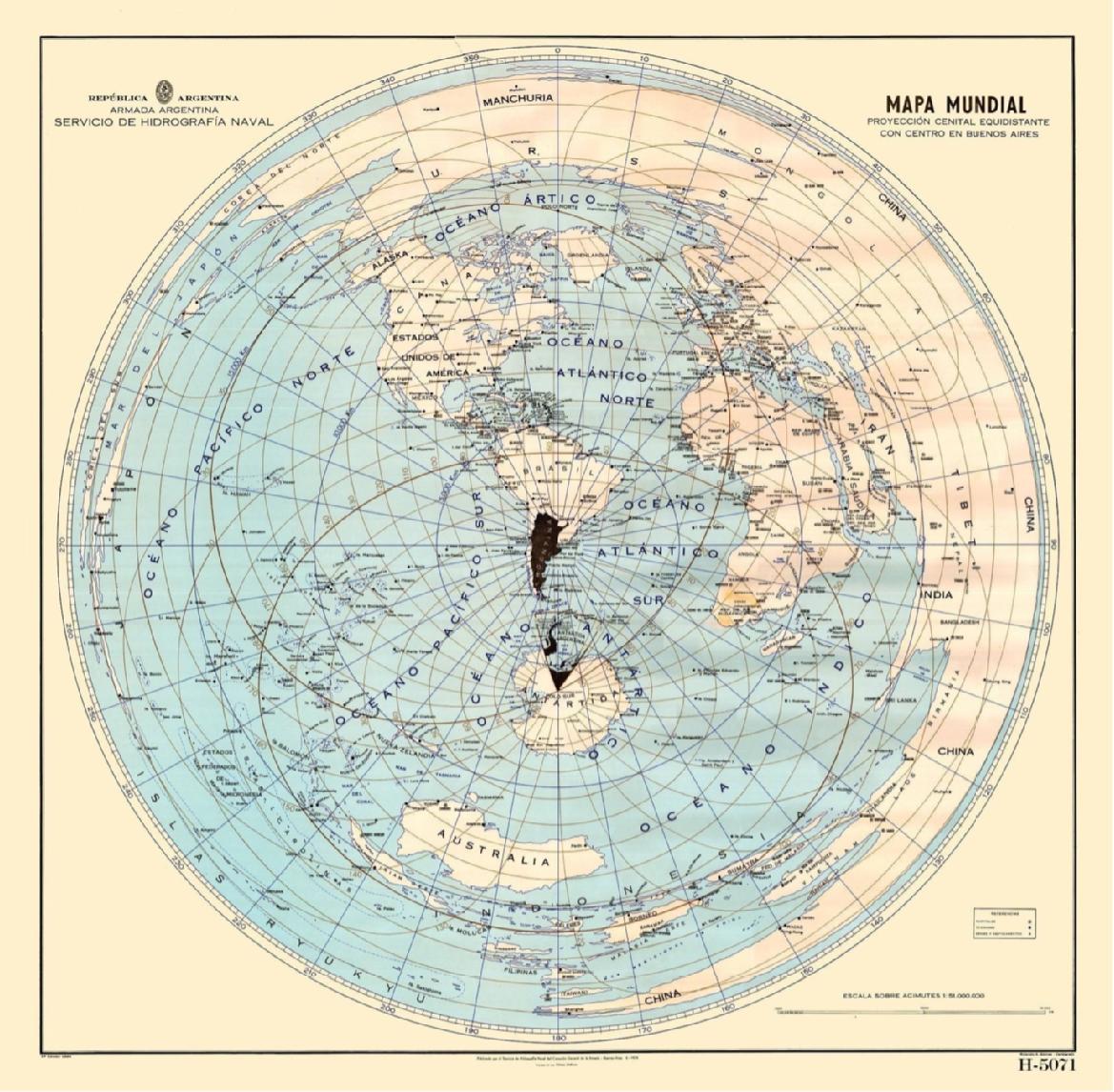

Since the 1980s, some people in Latin American countries, from both national institutions and also academia and the arts and culture, have been trying to represent the globe from a different perspective, a Latin American perspective. Argentina has been producing national and world maps from an “argentinocentric” perspective (figure 3), and many Chileans and Peruvians propose Pacific-centred maps as a way to better represent the global aspects of these countries through the Pacific and not the Atlantic Ocean.[4] A global history of Latin America may also, ultimately, help to understand how Europe can also be the “contact zone” and even the periphery of global processes, as for example the development of liberal states in the middle of the nineteenth century or the development of North American imperialism.

The fact that Global History is not very popular in Latin America doesn’t mean that it is completely absent. Recently, historians and academics from neighbouring disciplines are engaging in very good research from the region with a global history perspective.[5] Slowly, but firmly, many Latin Americanists formed in Europe and the United States are leading the Global History historiography. As Mathew Brown noted, there are specific moments in time when Latin America has been more “global”, and it is precisely topics related to these periods that are emerging as the focus of new scholarship, in Spanish, Portuguese, and English.

Figure 3. Mapa Mundial. Proyección central equidistante con centro en Buenos Aires. Servicio de Hidrografía Naval. Armada Argentina. Argentina. 1975.

Camilo Uribe Botta is a third-year PhD student in the History Department at the University of Warwick. He holds an MA in History from the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Colombia. His doctoral research centres on the commerce of orchids between Colombia and the United Kingdom in the nineteenth century. He analyses how tropical orchids, understood as a botanical curiosity, a scientific object and a commodity, impacted the economic, scientific and cultural relations between Colombia and Britain and the different actors involved in this trade. He is funded by the University Chancellor’s International Scholarship. He tweets at @curibottaLink opens in a new window.

[1] Matthew Brown, ‘The Global History of Latin America’, Journal of Global History, 10 (2015), 365–86.

[2] Gabriela De Lima Grecco and Sven Schuster, ‘Decolonizing Global History? A Latin American Perspective’, Journal of World History, 31.2 (2020), 425–46.

[3] Mary Louise Pratt, ‘Arts of the Contact Zone’, Profession, 1991, 33–40.

[4] Gregory T Cushman, Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

[5] Ana María Otero-Cleves, ‘Foreign Machetes and Cheap Cotton Cloth: Popular Consumerism and Imported Commodities in Nineteenth-Century Colombia’, Hispanic America Historical Review, 97.3 (2017), 423–56; Sven Schuster and Laura Alejandra Buenaventura Gómez, ‘Imaginando la “tercera civilización de América”: Colombia en las exposiciones internacionales del IV Centenario (1892-1893)’, Historia Crítica, 75, 2020, 25–47; Matthew James Crawford, The Andean Wonder Drug: Cinchona Bark and Imperial Science in the Spanish Atlantic, 1630-1800. (Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg Press, 2016).