The Pandemic, Privilege and Global History

Published: 25 June 2020 - Anne Gerritsen

When I sent out my questionnaire (see 'Global Historians reflect on a Global Pandemic') in early May, and when I started receiving replies later that month, Covid-19 was the main topic of conversation. When I was writing my earlier pieces that reflected on where we were during the lockdown and what the local meant to us as global historians, Covid-19 was still key. But their appearance coincided with the brutal killing of George Floyd at the hands of a Minneapolis policeman, and in that instance, the focus shifted away from Covid-19 and our individual experiences of the lockdown, towards the global responses to George Floyd’s death and the Black Lives Matter movement. In what follows below, I will share some of the responses of our community of global historians to my questions about the meaning of the global in light of the pandemic, before coming back to the question of what connects the experiences of the pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement.

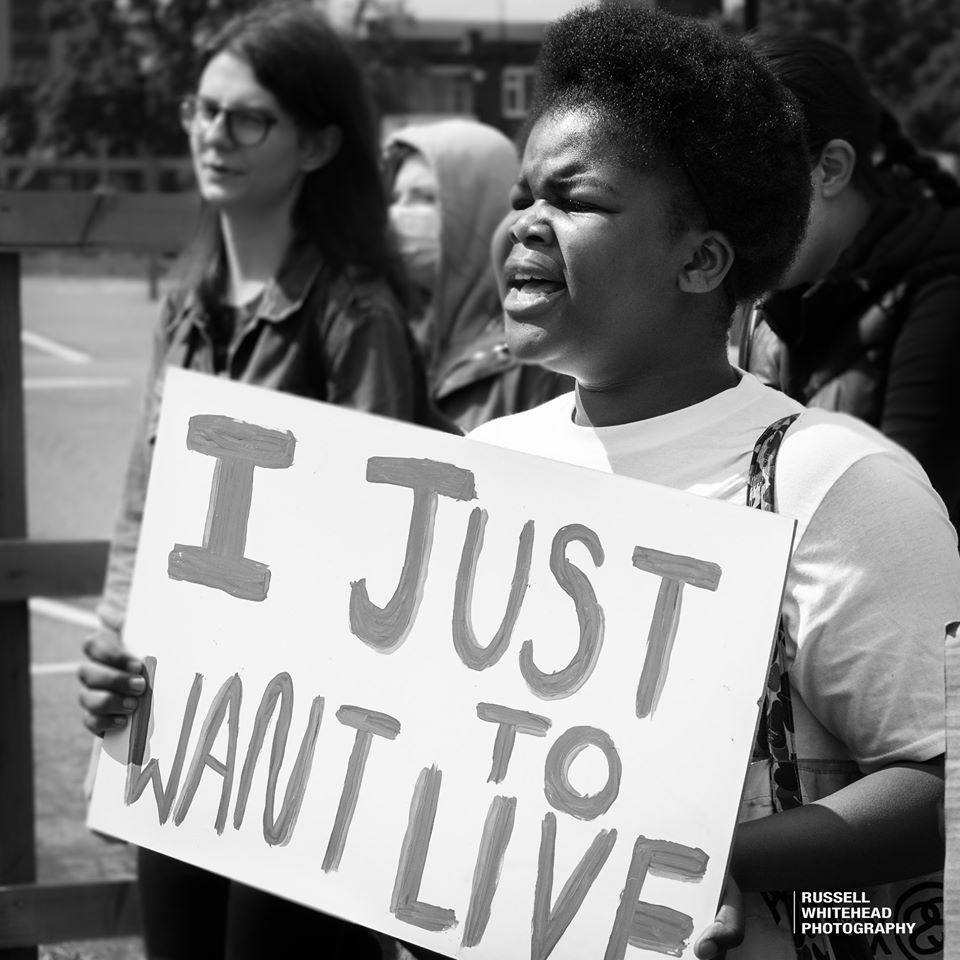

[Photo credit: Russell Whitehead Photography]

Black Lives Matter protest, Coventry, 20 June 2020. Photo by Russell Whitehead Photography: https://www.facebook.com/russellwhiteheadphotography/

In what ways has this felt like a ‘global’ experience?

At a certain level, my question was meant as a simple invitation to reflect on the ‘global’ part of the global pandemic. The replies were hugely varied, in every way imaginable, and I have tried to preserve some of that rich variety in my text below. People wrote in unexpected ways about how this global pandemic had an impact on their thoughts on the global, even though some also wrote in ways that matched their research interests beautifully, such as this scholar of Chinese material culture, who replied to my question: ‘What is ‘global’ about it to your mind?’ by mentioning ‘the unstoppable global flow of objects, embodied in the gift of facemasks from an academic organization I have worked with in Hangzhou, the box just turning up on the doorstep.’

One type of response to my question came in many variations on the theme of ‘it’s global because it’s happening everywhere’.

‘As a student of global history, this felt truly planetary in scope. Friends everywhere have reported some kind of pandemic activity in their region; and lockdown measures seem to have been fairly universal (Except countries which deny Covid that is).’

Or:

‘It is in every newspaper I read (UK, Australian, German, and Spanish) and they all reference each other.’

Another said: ‘I have been able to discuss what is happening with friends and family around the world who are going through their own variation of it. We compare notes on how governments are responding and, in a bid to keep spirits up, laugh bleakly about the fact that we never see each other in person again.’ For many, the 'global' nature of the experience was most obvious in conversations with scattered friends and family, all ‘able to list off similar concerns and experiences.’

But at the same time, for some, the globality of the experience was immediately refracted by local circumstances:

‘To me, what’s global is that many are all locked down in such similar ways. For instance, I teach a course online to students in Vietnam. They have the very same questions as my students in Princeton and are living with their families in the same way my Princeton students are. What varies is fear and anxiety. Some of this is localized. My Princeton students, no matter where they are, feel strangely secure (in spite of what’s unfolding in Washington), while my students in other parts are more worried – even if they live in more healthy and secure places.’

Local differences

While many referenced the shared experience part in their reply, overall, far more respondents mentioned local differences than global similarities:

‘Well, it happened everywhere, but it also felt extremely local. I have barely moved an inch… So, in that sense it fits with my definition of the global interacting with local outcomes.’

‘This event is global in terms of geography but looking at it from a 'global' point of view, in terms of how to handle this global event, I feel we are not very global, we are very much local and individual.’

‘The global is experienced locally. That is my strongest impression, so far, concerning the pandemic. We are all facing the same virus, but it touches each country, each region, and each locality in distinct ways. I keep up, more or less, with media in the US, UK, and the Netherlands, and they all present a different tone and a different set of particular concerns.’

An ‘incidental global’

One respondent coined a specific term for this: ‘Being stranded from my family in India and friends in different parts of the world had its own effect. In our daily worries and fretting over each other's conditions, we also paid more attention to what was happening in those parts of the world - an incidental 'global'.

Clearly, our thought — that the global means a shared experience — is never far removed from our actual experience — that local differences are what separate us.

‘What feels global is the biological reality that everyone is facing. What feels local to me is how differently family members I know in different parts of the world – Cairo, Los Angeles, Edinburgh, and Paris – are reacting to it. Some send jokes, ignore social distancing advice, and go on with their lives as before, despite the lack of the safety net of nationalized health care; others take precautions very seriously. The gap between these two attitudes is a source of some tension and stress, which again increases the distance one feels between how individuals are responding to this global crisis in very different ways.’

Even the historical context within which the global pandemic is placed differs locally:

‘In East Asia now, the pandemic being similar to the SARS crisis looms large, whereas in the West, there is much more talk of the 1918-19 influenza, and in the United States there has sometimes been a curious obsession with parallels to 9/11.’

Are we, or were we, ‘global’?

Quite a few of us reflected on the ways in which we might have once thought of ourselves as global but now have to make adjustments to that image. For many of us, our identity as global citizens was connected to flying all over the world, and when that disappeared, then what?

‘The pace of life has slowed dramatically with less travel - so I feel both more connected and less.’

‘It made me realise how ‘global’ my life was before the epidemic hit. My ‘global’ life is now lost and who knows whether or when I’ll get it back. I was travelling and living in various worlds at the same time before the virus arrived on our doorstep.’

And that slowing down had advantages for many of us:

‘Now that a lot of people are cooped up at home, there is a need and an opportunity to hang out in groups, have game nights, Skype-drinks, etc. In that sense I do feel more connected with people across the globe.’

‘Now my life is reduced to a ‘national’ or even ‘local’ existence […] I have to admit I kind of like this new pace of life…[…] The reduction from the global to the local made me realise how crazy this ‘global’ life actually was and I feel that I don’t really want this craziness back….’

‘It has enhanced a sense I was already having of being spread too thinly, and needing to sink some deeper roots into the local place in order to maintain my balance! It does not feel like a good time to be a globe-trotting cosmopolitan academic!’

‘Positively, many of us academics have been traveling the world at a frantic pace and this has been a good stop to experience the routines of everyday life. Still, I feel a strong sense of guilt for being so privileged.’

One respondent even wrote about how this might change the practices in our field of global history:

‘Most of my colleagues outside of global history and global studies dream of a normality, which they hope to be restored in the near future. Meanwhile, at our institute the majority expresses the hope that less travel, more border-crossing co-teaching, and more communication with students in different parts of the world will become the new normality.’

The element of time

One striking comment that appeared in a few of the responses was the element of time. Time created difference in a number of ways: the outbreak happened in a sequence that theoretically should have offered those who came later more time to prepare (with many comments reflecting on failed responses and missed opportunities), but the pandemic also made us more aware of the shared experience of time:

‘Will we ever be at the same "point" in the pandemic? I am struck by how the rotation of the earth unites and separates at the same time. It is both sweet and bitter to have to leave an exchange of friendly messages because it is time to go to bed at our end. It is, to take up a phrase that has had some currency in connected history, a matter of asking ourselves "what time is it over there?"... but it is also, for the first time, I feel, a matter of not just asking once in a while. It is this crisis, really, that has made me aware of the global networks we are part of - and the amplitude of a planet performing a full rotation every 24 hours - in every single hour of every single day.’

The ubiquity of inequality

Indications of awareness of privilege and concern over inequality were scattered throughout the responses:

‘Sometimes you hear people say, 'we are all in this together.' But, I wonder. We are all in one of thousands of lifeboats on the same viral sea, and some of the lifeboats are more seaworthy than others.’

It led several respondents to ask who exactly is able to stay safe during this lockdown? Social distancing is as impossible for ‘street vendors and those living in very small houses’ in La Paz and Lima as it is ‘in some neighborhoods in the outskirt of Rome’. And who can feel assured in the ability of the government to provide appropriate healthcare and financial support for those whose livelihoods are affected, now and in the future?

‘How the coronavirus affects people's lives, of course, depends on where you are located and which class, "race" and gender you belong to. In other words, from its advent, the emergence of the global was based upon asymmetrical power relations that heavily increased in the course of history. … Whereas the effects of Covid-19 on the well-to-do are oftentimes less dramatic, the consequences for the poor in the global north and especially in the global south might be quite devastating as - compared to the privileged - so many more "subalterns" have lost their lives, family members, jobs and livelihood.’

'[This crisis has] sensitised us to the near-universal experience of migrant and casualised workers' precarity, the bullying of wealthy western countries (particularly U.S), labour exploitation, and the systematic erosion of public health infrastructures around the world. It made me think of the ways in which the crisis offers an extraordinary opportunity to redistribute wealth in the world; pay renewed attention to the notion of 'global commons' in our world.’

Black Lives Matter protest, Coventry, 20 June 2020. Photo by Russell Whitehead Photography: https://www.facebook.com/russellwhiteheadphotography/

Can institutions offer solutions?

Throughout the responses, there was broad agreement that in the case of this pandemic, the global has meant something along the lines of ‘it’s happening everywhere’, and the local has meant something like ‘the responses to the pandemic have not been the same everywhere’. But several respondents raised the question of where to look for responses. Could institutions offer the answer? Most felt disappointed by institutions.

‘The WHO, a global institution par excellence, seems to be impotent’.

‘When we look for solutions, we look to our national governments or the European Union. True, the World Health Organization, has never been so present in our lives, but the level of attacks this organisation is receiving, or its problems to make the governments follow their recommendations shows how far we are from trusting the global organisations as our saviours.’

‘We are all ready to point at global problems, or how global connections can transform someone else’s problem in our problem in a matter of weeks. However, very few people are talking about global solutions.’

There is a sense that if we are looking for solutions, this has to come from ‘a stronger decision making forum to tackle this kind of threat – a lesson that could be essential in the future fights against the climate change or the rising social inequalities of our societies.’

Cause for optimism?

For some, these global aspects of the pandemic provided reasons for optimism:

‘Global? Absolutely. We are witnessing a real-time display of different political systems and different heads of state and their ability to lead in a crisis. These systems will survive or change—global cooperation will end the virus.’

‘The remarkable change of the present situation is that literacy and linkage to electronic communication are now at such a high level worldwide that one can reasonably imagine a worldwide conversation on what beliefs we should try to share.’

However, not many saw reasons for optimism.

‘What happens next is very difficult to predict, but broadly the pandemic seems to have revealed an appetite amongst politicians and a willingness amongst the public to accept massive state intervention, from the economy right down to the details of everyday life. What people thought was possible only in China might start to become more frequent elsewhere, for better or worse.’

‘One can see how the mobilization to contain or manage the virus is a part of 'nation building' in some countries and nation-unravelling in others.

‘With the upcoming economic crisis, the interdependence of markets will become dramatically visible and could lead to a re-localisation process. If that process is necessary from an ecological point of view, it could, alas, make stronger nationalist perspectives all around the world. Paradoxically, what Covid could spread at a global scale is a xenophobic protectionism.’

Black Lives Matter

Perhaps the powerful surge of responses all over the world to the killing of George Floyd, and the shared sense of urgency behind the Black Lives Matter movement are in fact much stronger indications of what ‘global’ means than the pandemic itself. Of course, here, too, there are local iterations of the Black Lives Matter gatherings and there are vast differences in the ways in which our lives have been affected by racism. But as global historians, we are acutely aware of the global impact of the slavery, imperialism and colonialism that Western powers have used for centuries to shore up their sense of superiority. Much of what we research deals precisely with the multiple forms of inequalities between different parts of the world that slavery, imperialism and colonialism created and/or enhanced. Most of the inequalities we observe in the responses to the pandemic are legacies of precisely those institutions.

If these reflections on the global pandemic, seen in the light of the Black Lives Matter Movement, teach us anything, it should surely be that unless we address these inequalities and the persistent institutional and personal forms of racism that preserve them, the virus will remain amongst us. Whether that virus is called SARS-CoV-2, or racism, or inequality, it will continue to make this an unhealthy world. At the very least, we have a responsibility, as global historians, to continue to work towards a better understanding of that world.

Black Lives Matter protest, Coventry, 20 June 2020. Photo by Russell Whitehead Photography: https://www.facebook.com/russellwhiteheadphotography/