Technology as Resource: Material Culture and Processes in the Pre-modern World

WEHC 2022 Pre-session

April 4-5, 2022

Musée du Quai-Branly Jacques Chirac

Made possible by the support of the Musée du Quai-Branly Jacques Chirac, the Centre Alexandre Koyré UMR 8560, the lab ICT EA 337 (University Paris Cité), and the Global History and Culture Centre

Organisers

Liliane Hilaire-Pérez (Université of Paris /EHESS/IUF, France)

Giorgio Riello (European University Institute, Italy)

Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick, UK)

Programme Day 1

Programme Day 2

Programme with abstracts

Programme Day 1 (Room B310)

9.30-10.00

Marcos Camolezi (ENS), Liliane Hilaire-Pérez (Univ. Paris Cité/EHESS)

Technology and Technique: Resources for Economic Historians

Theme 1. New, Old and Lost Techniques

10.00-11.00

Sébastien Pautet (Univ. Paris Cité)

Transmission or Resurgence? Formalization of Knowledge, Competition and Invention in the Case of Chinese-European Horn Lantern Fabrication at the End of the 18th Century

Alka Raman (London School of Economics)

Evolution of Cotton Spinning Technology: Indian Cottons and British Industrialisation

11.00-11.30 coffee break

11.30-12.00

Ariane Fennetaux (Univ. Paris Cité), Emmanuelle Garcin (Musée des Arts décoratifs)

Quality, Durability, Repairability of Consumer Goods : Textiles

12.00-13.00:

Handling session: Ariane Fennetaux (Univ. Paris Cité), Emmanuelle Garcin(Musée des Arts décoratifs)

14.30-15.30 Room B310

Object-based presentation: Gaëlle Beaujean, Vincent Guigueno (Musée du Quai-Branly Jacques Chirac)

History, Technology and the Dakar-Djibouti Expedition

15.30-16.00 Coffee break

Theme 2. Techniques and Local Resources

16.00-17.00

Zhao Bing (CRCAO, CNRS), Philippe Sciau (CEMES, CNRS)

Brown-black-glazed stoneware in China: An ordinary widespread production and the exploitation of local resources (10th-14th century)

Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick, UK)

The tools of the trade: tools for ceramics manufacture in Jingdezhen and Delft

Programme Day 2 (Room B310)

Theme 3. Repair and Quality

8.45-10.45

Michael Bycroft (University of Warwick, UK)

Gem appraisal and the invention of applied science in France, 1800-1830

Marjoljin Bol (Université d’Utrecht)

Theorizing the Hard through Art: Making and Knowing Durability in the Pre-modern Period

Giorgio Riello (European University Institute)

To Twist and Turn: Silk and Quality in Medieval and Early Modern Italy

10.45-11.00 Coffee break

11.00-12.00

Group 1 - Muséothèque Céline Daher, Stéphanie Leclerc-Caffarel, Zoe Rimmer, Gaye Sculthorpe (BM): Tasmanian Aboriginal kelp water containers

Group 2 - atelier Martine Aublet : Wampum exhibition https://www.fondationmartineaublet.fr/wampum-perles-de-diplomatie-en-nouvelle-france-1?context=5a1c154

12.00-13.00

Group 1 - atelier Martine Aublet : Wampum exhibition https://www.fondationmartineaublet.fr/wampum-perles-de-diplomatie-en-nouvelle-france-1?context=5a1c154

Group 2 - Muséothèque Céline Daher, Stéphanie Leclerc-Caffarel, Zoe Rimmer, Gaye Sculthorpe (BM): Tasmanian Aboriginal kelp water containers

13.00-14.30 Lunch

14.30 – 15.50: Final discussion

Programme with abstracts

Day 1. Room B310

9.30-10.00 Marcos Camolezi (ENS), Liliane Hilaire-Pérez (Univ. Paris Cité/EHESS)

Technology and Technique: Resources for Economic Historians

Economic historians are getting increasingly concerned with questions raised by terminology for analyzing production at a global scale. This growing concern is revealed by attempts to contrive new expressions such as “useful and reliable knowledge,” and also by recent studies bringing the Eurocentric notion of technology into question in non-European contexts. Creating new words and expressions and analyzing those which already exist are crucial initiatives as global history of economics both evolves into the history of arts and crafts, and takes into account local exchanges within global circulations. That way, the noun “technology” no longer seems to be suited for building up narratives that are capable to include, on the one hand, the diversity of labor organization, and, on the other hand, the words through which linguistic communities express their own activities. For almost a century, the word “technology” was an omnipresent term used to boundlessly represent human objects, methods and activities invented from prehistory to nowadays. However, an historical and critical reflection could reveal that “technology” is a vernacular noun which massive use could be explained by the ideology of progress and modernization. Are “technology” and “technique” mutually replaceable? We now can establish that “technology” and “technique” have different origins and different meanings which emerged through historical processes within linguistic communities. Therefore one could ask if “technique” might express more widely human activity beyond applied science, and then be an intellectual resource for economic historians.

10.00-11.00 Theme 1. New, Old and Lost Techniques

Sébastien Pautet (Univ. Paris Cité)

Transmission or Resurgence? Formalization of Knowledge, Competition and Invention in the Case of Chinese-European Horn Lantern Fabrication at the End of the 18th Century

1793, French Revolutionary wars. In Brest, the French Navy faces difficulties to import horn plates used to protect lanterns on board. The Parisian authorities assess a scholar and expert of the navy to build a fabric of horn lanterns in emergency. Rochon crosses his memories of travels in Asia with available bibliography on lanterns and horn. The technics that emerge from his research is surprising. Indeed, a Chinese technic of luxurious traditional horn lantern transmitted by a French missionary of Beijing in the 1750s resurges in 1793 in order to build military supply. European technologies existed however at the same time. This communication follows the circulation of technology from China to Europe in order to understand why an old Chinese technical knowledge improved French production of horn lanterns at the end of the 18th century.

Alka Raman (London School of Economics)

Evolution of Cotton Spinning Technology: Indian Cottons and British Industrialisation

The pre-industrial technology of spinning cotton yarn on the jersey wheel of Indian origin was readily available to all economies of the world for the replication of Indian cotton yarn, and subsequently the cotton cloth. What, then, explains the mechanisation of spinning through the successive technological developments of the spinning jenny, the waterframe and the mule? This paper introduces a distinction between the existence of a technology and its successful deployment. It argues that any technology is valuable only in so far as the labour force possesses the skill to use it optimally. It highlights that in pre-industrial Britain, the skill to spin fine yet strong cotton warp, to match the quality of Indian cotton warp, was missing using the pre-existing technology of the jersey wheel. Therefore, successive mechanisation in spinning was necessary if the quality of Indian cotton textiles was to be matched in Britain.

Evidence from the analysis of the working mechanisms of spinning machinery over time demonstrates that producing improved quality of spun yarn was a key driving force for new machinery, especially the mule. This mechanical evidence corroborates the quality-focussed improvements in British cottons over time from the material textile evidence. It also shows that the three key spinning machines were fundamentally path dependent, with the jenny and the mule based on the jersey wheel technology of Indian origin and the waterframe upon the Saxon wheel technology from Europe. Further, it argues that the skill to use a technique successfully is a key component of any technological paradigm, and a combination of a technique and the skill required for its use alongside a particular fibre staple determine the quality of yarn and final cloth, not the staple of the fibre in isolation.

11h30-12h

Ariane Fennetaux (Univ. Paris Cité), Emmanuelle Garcin (Musée des Arts décoratifs)

Quality, Durability, Repairability of Consumer Goods : Textiles

The presentation will centre on the interconnected issues of quality, durability, repairability of consumer goods with a particular emphasis on textiles (taken as an example/ illustration of more general points rather than as specific case study)

It will start with the somewhat polysemous notion of quality which economic historians may tend to align with production processes (quality control etc.) but will look at it from a material point of view. What does quality mean materially? How can it be defined (if it can). The presentation will be based on the analysis of some pieces in the study collection of the MAD museum. The changing definition of quality as industrial production gathered pace will be considered in relation to durability and the ability (or not) to both repair (for users) and conserve (for museum professionals) and lead us to reflect on the importance of these issues for historians for whom material sources represent irreplaceable evidence difficult to garner from other - more traditional sources.

12h-13h : Handling session Ariane Fennetaux (Univ. Paris Cité), Emmanuelle Garcin (Musée des Arts décoratifs)

13.00-14.30 Lunch

14.30-15.30 Room B310

Object-based presentation Gaëlle Beaujean, Vincent Guigueno (Musée du Quai-Branly Jacques Chirac)

History, Technology and the Dakar-Djibouti Expedition

Supported by the French Government and a national decree, the ethnographic and linguistic Dakar-Djibouti expedition [1931-1933] crossed 17 African countries during the colonial period. The expedition gathered a team with multiple scientific and literary backgrounds. Today, the musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac has joined forces with a team of researchers in France and in several African countries to re-examine the heritage of this mission.

The question of “technology” is an important one for the mission, which described in details – through notes, sketches, pictures - an impressive range of domestic and collective techniques. Our research will be conduct with a diachronic angle – how the ethnographers addressed the issues in the 1930’s - but also from the point of view of the place of the techniques used by the mission itself . The presentation will also present the results of the expedition for the collection of objects, specimens, information, and sound and image recordings.

15.30-16.00 Coffee break

16.00-17.00 Theme 2. Techniques and Local Resources

Zhao Bing (CRCAO, CNRS), Philippe Sciau (CEMES, CNRS)

Brown-black-glazed stoneware in China: An ordinary widespread production and the exploitation of local resources (10th-14th century),

The plain brown-black-glazed stoneware (without decoration) is an ordinary production that is widespread throughout China from the 3rd century AD to the present day. The technique, being less sophisticated and having not evolved much over the time, is totally neglected by current studies, which are still largely confined to a qualitative approach due to the long Chinese tradition carried out by Chinese literati and art merchants. However, since the potters used mainly (or exclusively) local raw materials, this very production offers great potential for studying the plurality of the ceramic production in China, largely linked to natural and human local resources.

As a test, we propose to study the production of the 10th-13th centuries, period during which the phenomenon of imitation production is particularly interesting. Precisely, we propose to focus on the structure of the sherds excavated from the Yaozhou kiln site, the Jian kiln site and the Tianmu kiln site. Our preliminary consideration will be based on our own investigations in laboratory and on a compilation of available physico-chemical data, historical and archaeological data.

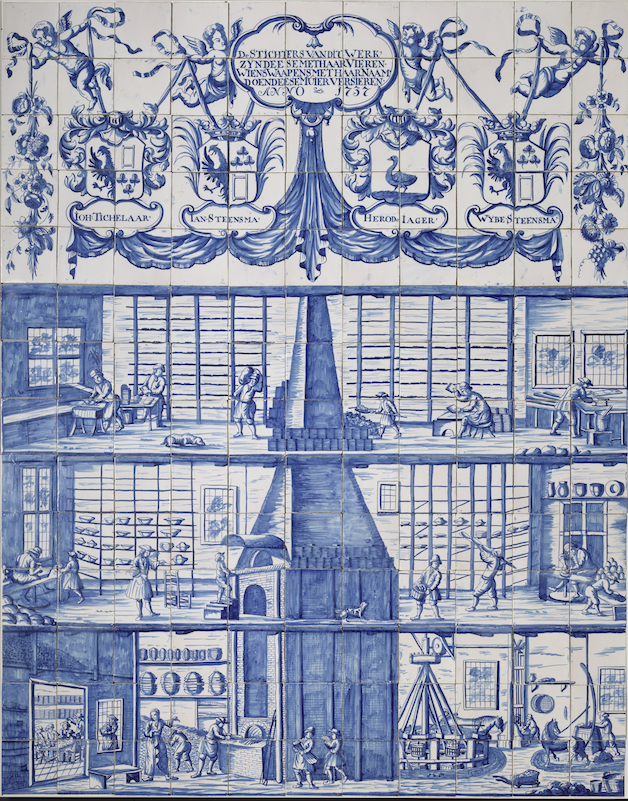

- Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick, UK)

The tools of the trade: tools for ceramics manufacture in Jingdezhen and Delft

This short paper will focus on visual representations and material remains of the tools used in ceramics manufacture. My focus will be on representations of production in the seventeenth-century Netherlands and China, and Delft and Jingdezhen specifically. These tools, including saggars and tubs, stools and planks, are ubiquitous in ceramics manufacture, and thus have a certain universality about them. But they work as resources in different ways, and to study such tools in contexts, including the chaîne opératoire, allows us to highlight the particularities of the skills, technologies and material resources of these particular production complexes.

Day 2.

9.00-11.00 Room B310

Theme 3. Repair and Quality

- Michael Bycroft (University of Warwick, UK)

Gem appraisal and the invention of applied science in France, 1800-1830

What is technology for? Most answers to this question revolve around the notion of production. On this view, technologies help to make things. But this is only one side of the coin. Technologies also help to evaluate things, to determine how good they are. I illustrate this with reference to a crucial phase in the history of useful knowledge, the period in which the very idea of applied science, or “science applied to the arts,” came into existence in France. Applied science was one answer to the question of how science could be both useful and technical. The challenges of this project were nowhere more apparent than in the case of gem appraisal. Gems had been appraised for millennia, using techniques that ranged from visual inspection to sophisticated balances. Around 1800, European mineralogy was transformed by the use of chemistry and crystallography to classify minerals. The result was a “science of precious stones applied to the arts” (science des pierres appliquée aux arts). This new science aimed to replace the old methods of gem appraisal with new ones that were alleged to be more precise and more reliable. The fortunes of this project show the importance of material evaluation in debates about the merits of different kinds of technology, including the technologies of scientists, artisans, merchants, and connoisseurs.

- Marjoljin Bol (Université d’Utrecht)

Theorizing the Hard through Art: Making and Knowing Durability in the Pre-modern Period

This paper explores how artisanal knowledge of the stability and aging properties of materials and processes influenced thinking about the workings nature, and how “durable” nature could be recreated artificially. Its main sources are recipes on art technology, the natural history of metals and stones, and alchemical treatises theorizing material hardness through processes of congealment and coagulation. These authors often use the idea that art imitates nature to prove their theories. This was not just a commonplace but a fundamental way of thinking about the genesis of materials in the natural world. Those theorizing nature looked towards the art of ceramics to explain the hardening processes that form rocks and mountains, or towards the art of glass for ideas about the hardness of precious stones and the permanence of their colors. In his 1661 treatise on the History of Fluidity and Firmness Robert Boyle, for instance, theorizes firmness and durability by studying different forms of weaving. He explains how twigs “when lying loosely in a heap together, may each of them very easily be dissociated from the rest; but when they are breeded into a basket, they cohere so strongly, that when you take up any of them, you shall take up all the rest.”

Indeed, premodern theories about stability and durability are deeply intertwined and indebted to craft practice. And, as this paper aims to show, this long history of theorizing the hard through art is fundamental to the development of our modern thinking about what constitutes the “durable”.

- Giorgio Riello (European University Institute)

To Twist and Turn: Silk and Quality in Medieval and Early Modern Italy

A huge barrel-frame, stacked with multiple rows of spindles and reel, embellishes the Trattato dell’arte della seta in Firenze, a 1486 manuscript of used by artisans and traders to promote new silk industry of Central and Northern Italy in the fifteenth century. The drawing is the earliest European image of a torcitoio (twisting machine) and it shows a complex machine that combines silk reeling and throwing. Images such as these have time and again served to placard arguments about an intimate connection between invention and innovation in which machines helped to boost production and productivity by deploying new uses of (non-human) energy, such as animal, water, or steam to help scale up manufacture, thus expanding markets and favouring mass consumption. Yet, pre-modern European artisans, craftsmen and entrepreneurs considered reeling methods as a major way for improving the quality of finished products thus avoiding unnecessary waste caused by spoiling expensive raw silk through faulty processing. Quality is here not just an attribute of the finished product but also a characteristic of the process of production itself. A complex machine to spin (filatoio) or twist (torcitoio) silk composed of a fix cylindrical structure with an internal frame rotating vertically was first introduced in the city Lucca in Tuscany in the twelfth century. This machine solved a major problem: hand-spinning or twisting with a wheel could not provide a homogenous torsion as there was a lack of coordination between the turns of the spindles and the turns of the reel. The Bolognese and later Piedmontese systems of silk throwing and reeling can be read as part of a trajectory of quality ‘upgrade’ viz-a-viz the silk cloth and yarn produced in China. While this paper focuses on technologies and their impact on quality in early modern Italy and Europe, it also considers practices, most especially in the complex natural handling of silk cocoons.

10.45-11.00 Coffee break

11.00-12.00

Group 1 - Muséothèque Céline Daher, Stéphanie Leclerc-Caffarel, Zoe Rimmer, Gaye Sculthorpe (BM): Tasmanian Aboriginal kelp water containers

Group 2 - atelier Martine Aublet : Wampum exhibition https://www.fondationmartineaublet.fr/wampum-perles-de-diplomatie-en-nouvelle-france-1?context=5a1c154

12.00-13.00

Group 2 - Muséothèque Céline Daher, Stéphanie Leclerc-Caffarel, Zoe Rimmer, Gaye Sculthorpe (BM): Tasmanian Aboriginal kelp water containers

Group 1 - atelier Martine Aublet : Wampum exhibition https://www.fondationmartineaublet.fr/wampum-perles-de-diplomatie-en-nouvelle-france-1?context=5a1c154

Water containers made of kelp from Tasmania are one of the rarest object types found in ethnographic museum collections. There are only two documented historic examples still extant. The British Museum holds one given to it 1851, by Joseph Milligan, after its display with several other Aboriginal objects at the Great Exhibition of London. In late 2019, an older example was rediscovered, mislabelled, amongst the African collections of the Musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac. This one was collected during the expedition of Antoine Bruni D’Entrecasteaux in southern Tasmanian in the early 1790s. Remarkably, in 2020, another historic example was brought to attention by a private collector in Canberra, Australia.

The identification of the one in Paris was achieved through the collaboration of both the MqB and British Museum staff working with the National Natural History Museum in Paris. Infrared analysis was used to compare the kelp of the MqB container with kelp samples collected housed at the Natural History Museum, Paris.

This workshop provides us with an opportunity to continue and extend this research collaboration by bringing together all three kelp containers together in Paris, along with a recently made ones now in the collections of the Natural History Museum in Le Havre.

Representatives of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community, scientific staff and curators will work together and, through visual and infrared analysis compare the manufacture and detail of each of these examples, in order to come to a better understanding of these rare objects and the long lost techniques they illustrate.

13.00-14.30 Lunch

14h30 – 15h50

Final discussion

Rijksmuseum BK-NM-5853