Posts

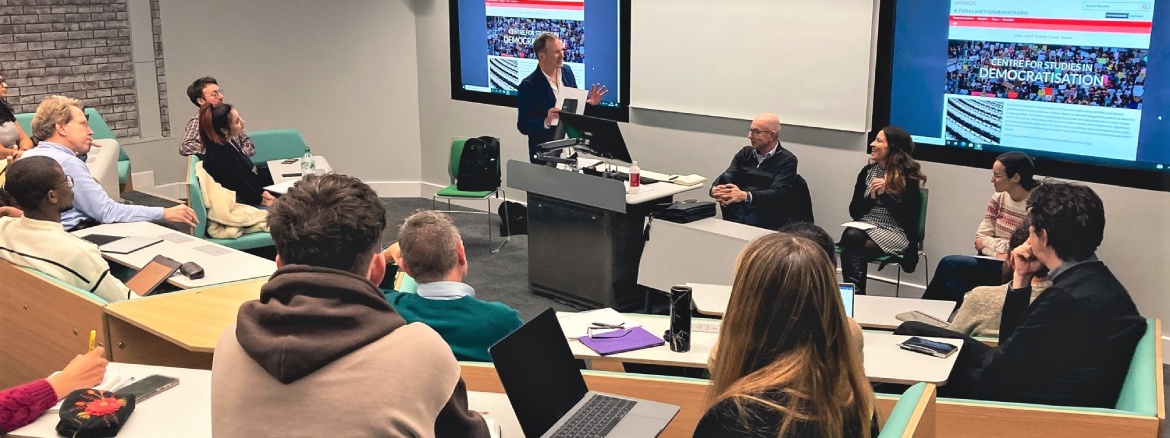

CSD re-launch event

On 7 December, 2022, the Centre hosted a special roundtable discussion on ‘Populism: challenges and responses’, featuring Ozlem Atikcan (Warwick), Soraya Hamdaoui (Warwick), and Simon Tormey (University of Bristol). The event was chaired by Michael Saward (Warwick). This was a re-launch event for the PAIS Centre for Studies of Democratization.

Three doctoral candidates at the Department of Politics and International Studies at Warwick wrote short comments after the event, which you can read below.

I thought the event was very engaging. The panel provided a strong introduction for those who do not work deeply on populism, and I particular liked the fact that it also managed to make what I thought were some genuinely novel interventions in the field. The concept of ‘anti-populism’ was intriguing; though at one point Soraya made a neat separation between those who are anti-establishment and those who are anti-populists, which for me prompted the question: could there be groups/people/communities that are simultaneously anti-establishment and anti-populist? Two other take-aways from the panel were particularly thought-provoking. The first was Simon’s argument about how, much like totalitarianism, populism has become somewhat of a ‘boo word’ in public discourse as well as in academia, and that there may be (and perhaps should be) a way to reconceptualise the democratic positives of populism, not simply to repeat the Mouffe/Laclau position but to reimagine populism positively in current debates. The second was the discussion on how populism can become a tool or a lens to gauge what is lacking in what the panel called ‘democratic style’ (which I understood as following Moffitt’s conceptualisation of populist styles). This was insightful for me and provided also a more action-oriented note to the overall discussion. This helped end the roundtable on a more optimistic note, I thought, unlike the more cynical/pessimistic tone that often pervades academic conversations on global populisms and democratic backslides.

Mouli Banerjee, Doctoral Candidate, Politics and International Studies

The session challenged much of the conventional wisdom about populism that we often see in mainstream political commentary. Rather than outlining a one-dimensional analysis focused on how to ‘defeat’ a conceptualisation of populism which is implicitly undesirable, the panel led us to give equal consideration to what democratic sicknesses a better understanding of populism might help us to cure, rather than simply seeking to cure populism itself. In this sense Simon Tormey’s invocation of Derrida’s concept of the pharmakon was insightful, leading us to consider the possibility of populism as a toxic substance which may also have the potential to heal us.

The different disciplinary backgrounds and approaches of the panel members highlighted why it is such a slippery term. Some panel members centred their definition more around style and the cyclical nature of populist flareups in response to crises; others focussed on the role of populists as external status-quo disrupters, or as practitioners of anti-elite or anti-establishment rhetoric. This interdisciplinary approach to definitions left me questioning the extent to which its dominant definition as a ‘thin ideology’ can capture the many facets of populism which relate to the disruptive vox populi style and practice that elicits such a unique response from the demos. In other words, might we also consider populism as verbal – an action or practice - as well as an adjective that can be bolted on to a ‘thicker’ ideology?

The panel concluded with a fascinating conversation about the centrality of opposition to our current conceptualisation of populism. Empirically, we know that populists often struggle to maintain their style and popularity when faced with the cold reality of governing complex societies, but this discussion also led me to wonder whether even attaching the label of populists to governing elites becomes increasingly difficult as they become more institutionalised over time? It made me think of my own research into contentious referendums, and about Brexit specifically – at what point do the populist insurgents become the out of touch elites and vice versa?

Louis Stockwell, Doctoral Candidate, Politics and International Studies

The round table on ‘Populism: challenges and responses’ dealt with the key issues related to contemporary research about populism, mainly from a theoretical perspective. The debate started with the question that has haunted the studies of populism from the beginning – what populism really is and how contemporary theoretical reflections are evolving. Panellists dealt with the term differently in their research, and therefore the discussion featured a range of interpretations – from strategic characteristics of populism, through interpretations based on political style and the emotions, to the approaches to populism from the perspective of its political enemies.

The debate revolved around the question of the uneasy, sometimes problematic relation between populism and democracy. Despite their different theoretical approaches, the participants tackled the problem independently of these frameworks or “schools.” It emerged that it is not necessary to describe the populist political subjects as exclusively populist; their politics should always be considered populistic relative to the specific political context. Consequently, populism as a set of characteristics (anti-establishment, appeal to the people against elites, etc.) may not describe accurately a particular political leader or party but rather may be a style or tool that is applied when convenient. Consider the politics of government and opposition. Populism is a political style suited to opposition because of its anti-establishment outlook. It must face its paradoxical character when it is a part of the establishment.

These observations are not radically new. However, they underline populism’s lack of an ideological core (as expressed by Simon Tormey) – a perspective that helps to untie the hands of contemporary scholars of populism because it highlights the variability of populist politics. I find this moment in the discussion crucial since it helps us to understand the behaviour of political leaders that, on the one hand, use a populist political style to mobilise constituencies and assert their closeness to the interests of the people, and on the other hand, present themselves as possessing political and technocratic abilities that make them the only capable leaders.

Overall, the roundtable was an interesting contribution to the contemporary discussion of evolution in studies on populism. It showed that the strategic or minimal concept of populism significantly influenced all participants. Although the discussion did not address all prominent approaches, one conclusion was that overcoming misunderstandings among distinctive approaches can lead to fruitful research on populism. It seems that the future of populism studies lies in interdisciplinarity and the use of different approaches as complementary.

Kristian Temin, Doctoral Candidate, Department of Political Science, Charles University (Prague) and Visiting Research Student at the University of Warwick in 2022