Desi Writing Blog

Vernacular Voices:

British South Asian Writing in Punjabi, Urdu, Gujarati and Bengali

Welcome

These blog posts are short pieces on aspects of the British Asian vernacular literary world. Writings in South Asian languages by authors who settled in the UK from the 1950s come in the form of poetry, short stories and occasionally novels. These authors are rarely known outside of the language communities and thus these posts give an insight into them and their writings as well as a general idea of publishing and publications in the literary formation.

Follow Us

The Stranger's Door

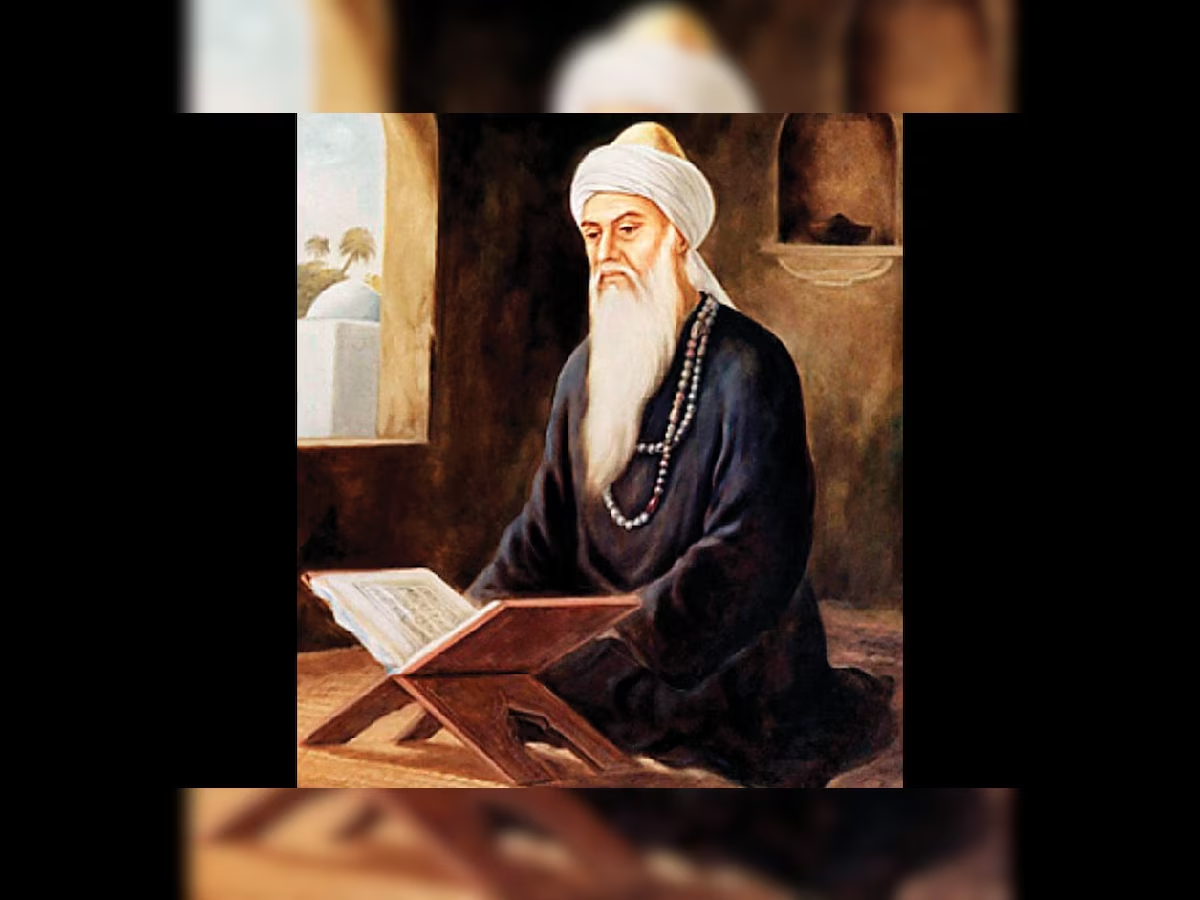

Baba Farid, a 12-13th century Islamicate mystic who settled in Pakpattan and whose shrine dominates that town is perhaps an odd poetic inspiration for migrant writers.

Nonetheless, his poetry is replete with metaphors that have stood the test of time. An apt illustration is the recent poem by Surjit Patar, title Ardas looking at the issue of migration, from the point of view of the sending place, is an apt starting point:

ਆਪਣੇ ਡਰ ਤੋਂ ਡਰ ਕੇ

ਸ਼ਰਮਸਾਰ ਹੋ ਕਰਦਾ ਹਾਂ ਅਰਦਾਸ :

ਜੋ ਜਿਸ ਧਰਤੀ ਜੰਮੇ ਜਾਏ

ਉਸ ਨੂੰ ਓਥੇ ਹੀ ਰਿਜ਼ਕ ਥਿਆਏ

ਇਹ ਕਿਉਂ ਕਿਸੇ ਦੇ ਹਿੱਸੇ ਆਏ

ਬੈਸਣ ਬਾਰ ਪਰਾਏ

ਜਿੱਥੇ ਲੋਕੀਂ ਆਖਣ ਸਾਨੂੰ

ਇਹ ਕਿੱਥੋਂ ਦੇ ਜੰਮੇ ਜਾਏ

ਮੈਲ਼ ਕੁਚੈਲ਼ੇ ਕਾਲੇ ਪੀਲੇ ਭੂਰੇ ਪਾਕੀ

ਏਥੇ ਆਏ

ਜਾਂ ਫਿਰ ਸਾਰੀ ਧਰਤੀ ਇਕ ਹੋ ਜਾਏ

ਕੋਈ ਨ ਕਹੇ ਪਰਾਏ

ਇਹ ਮੇਰੀ ਅਰਦਾਸ !

Scared of my own fear

Ashamed, I make a prayer/supplication

Wherever you are fated to be born

Let that land be able to feed you

Why is it in some’s ledger

To live a stranger’s life

Where people say to us:

Where were these born?

Dirty, black, brown, Paki, Coming here!

Or then let the world be one

Where no one is called, ‘stranger’

This is my prayer

Punjai poet laureate, Patar evokes Baba Farid in the fifth line of the extract with a play on the well know couplet:

ਬਾਰਿ ਪਰਾਇਐ ਬੈਸਣਾ, ਸਾਂਈ ਮੁਝੈ ਨ ਦੇਹਿ

ਜੇ ਤੂ ਏਵੈ ਰਖਸੀ ਜੀਉ ਸਰੀਰਹੁ ਲੇਹਿ ॥੪੨॥

Saved for us in the Ad Granth, Baba Farid’s terse style lends itself to multiple interpretation. The first line of the dohra (rhyming couplet), ‘Oh my master/beloved, please don’t make me sit at a stranger’s door’. Whilst this is a lament, it is further compounded by the second-line, response, in Farid’s typically direct and dramatic manner:’ If you must keep me in this way, then take the life from this body.’

In a literal reading, the couplet resonates with the migrant condition. In 1981 my father’s (Surjit Singh Kalra) first collection of short stories was titled Baar Praiye (Stranger’s door).

In 2019, British based, diasporic literary, organisation, Punjabi Sath released an edited volume of over 60 writers from Canada, USA, Europe, East/West Punjab and the UK, reflecting on the migrant life and diasporic condition, titled, Baar Praiye Baisna (Sitting at the Stranger’s door).

Entering into the mind of the writer-migrant, an interpretation of the poem raises the question of who is making the subject stay in a place that is not of their choosing. The sain, the beloved, the master, who has left the desiring subject not outside their own door but at ‘another’s’ door. Who is behind the door that the character finds themself. When the beloved, sain, the master who materialises as the sant, the pir, the spiritual figure, the object of love, (for some, more abstractly as the creator, Allah, Har) created through the human’s need for connection for bonding for being a devotee, leaves the lover pining. In this state, there is only wretchedness, but there is also a demand to not be left in this state. But this refusal is problem. Do not leave me as a sacrifice at another’s door. We are not accepting our fate here, the will of the sain is not being followed. But then the second line is a demand to take the soul out of my body. We see a pleading in the first line, almost a supplication and a whine, but the second is a surprise, the tone changes it is as if Farid is playing on the word sacrifice through repetition, Baar and Deh; to immediately ask for a different level of sacrifice, of life itself.

Who makes us move to another’s door? Individual acts of mobility, in the face of inequalities of economic opportunity? The need to sustain the body? To enable its reproduction, to maintain its existence. Thus being placed at another’s door is an invitation to enter, to explore the place of ‘another’ to abandon the way of the Sain to follow the way of the secular, to cut your hair, throw away the prayer mat and cut the sacred thread. A test to engage in other desires. Sparing and austere, Farid comes to the diasporic writer as a solace and resolve. The grim reality of the cold streets, the grey monotonous buildings and pale faces, is matched by a resolve to stay, come what may.

Rather than indulge this temptation, to open the ‘other’s door,’ Fareed, as devotee, offers a sacrifice, his essence, his life. But the body can remain. A depiction of the life of the migrant, empty of soul, functioning as a machine in the factory systems of old and the truck driving of the present day. Emptied from a purpose other to socially reproduce, literally left as a kalboot, that body, that author Waris Shah uses to describe the lover, Ranjha, as he leaves his village, to head on an epic journey in the 18th century love-tale, Heer-Ranjha.

Others may interpret this couplet in relation to an internal conflict. The devotee’s mind is swirling in negativity and confusion and this is represented by being out of place, sitting an an-other place. This is not a natural state of mind. So the request is to leave this condition, to literally take the life out of this alienated body. In a state of equipoise the other’s door would not be a hostile place, but one of engagement, but this is not possible as we are estranged from ourselves. To undo this state the appeal is to take this kind of state out of my body. If a life where the devotee is dis-connected, estranged and alienates is all that is on offer, then it is better to be done with the world. Just as Surjit Patar pleas for a world without borders, where there is no need to become a stranger just for the pursuit of daily bread.

Three hundred years later, Baba Nanak reflects on the same problem, but here with a much softer tone and infused with love, though the message is equally a matter of sacrifice.

My estranged/foreigner/away from home life, how did you get entangled in this web

If you kept the true master in your mind, you would be released from the trap of death

So the same life that is being asked for release by Baba Farid, is here trapped in a web of worldly attachments. Here recognise that death is the entrapment and that the sain/sacha sahib resides within you, it is a matter of clearing away the cobwebs which limit your perception. Here managing the diasporic condition is simply a matter of shifting consciousness. Wherever the human finds itself the answer to their problems reside within and their surroundings are merely distractions, illusions to keep them from recognising salvation is within.

This dialogue within the tradition, that moves through time is lost in the ravages of colonial thought. Modern education confines the sources of knowledge, so it is left to the Punjabi writer to re-articulate old wisdom in the face of a new forms of separation. It is in this way how Baba Fareed still continues to enable understanding more than 800 years after his birth.