Think Development Blog

Aid cuts by the West threaten a tragic spike in AIDS-related deaths, new infections and drug resistance worldwide

Western governments––from Washington to London to Brussels––are slashing foreign aid budgets. The United States has abruptly cut 83% of USAID-funded programs, with similar moves from other major donors: Belgium (25%), the Netherlands (30%), France (37%), and the UK (40%). This is not just routine fiscal tightening, it is a ticking time bomb. These abrupt cuts risk triggering millions of preventable deaths and new infections––and worse, a surge in drug-resistant HIV strains that are harder to treat, while contributing to the global crises of antimicrobial resistance (AMR), one of the deadliest global health threats.

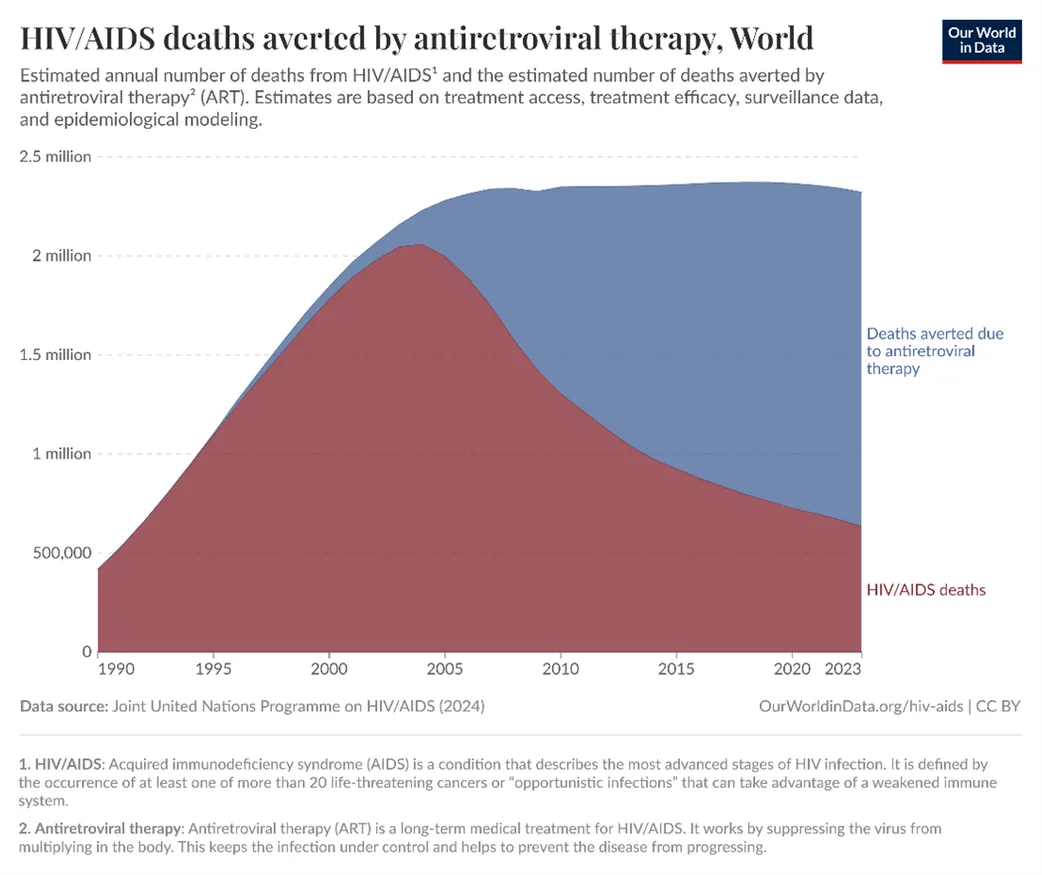

Since the peak of the epidemic, HIV/AIDS deaths have declined by ~50% globally, and new infections dropped by 60% (Figure 1). Thanks to global investment in antiretroviral therapy (ART), particularly through President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), AIDS is no longer a death sentence. This flagship program has been credited with saving approximately 26 million lives, enabling people to live longer, healthier lives. ART is a proven prevention tool––Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U), meaning a person on effective treatment cannot sexually transmit HIV.

Figure 1: Deaths averted by ART

Foreign aid cuts threaten a spike in new infections. This aid sustains life-saving AIDS programs through funding of testing, harm reduction and PrEP. Regions like the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is experiencing a sharp rise in new HIV infections, up 116% between 2010 and 2023, due to political instability, mass displacement, and growing refugee populations living in precarious conditions. Yet HIV funding in the region meets only 15% of estimated needs. UNAIDS, a major funder in MENA, is now facing a severe funding crisis due to its dependence on USAID and other traditional donors. As in Sub Saharan Africa, mobilizing domestic resources remain a challenge in MENA due to ongoing economic crises, restrictive laws, and pervasive stigma and discrimination.

Abrupt treatment interruptions from foreign aid cuts also threaten ART adherence. Even brief interruptions can lead to immune deterioration, resurgence of opportunistic infections (OIs), and multi-drug resistant HIV. Viral rebound from interrupted ART creates the perfect storm: resistant strains, transmission to others, and shrinking treatment options. Treating OIs often requires intensive use of antimicrobials, but this heightens the risk of AMR. In 2019 alone, AMR caused an estimated 1.27 million deaths and contributed to 5 million more. WHO recently reported concerning levels of HIV drug resistance in Africa, exceeding 10% of new infections in some countries already resistant to first-line drugs. Moreover, untreated HIV with high viral load vastly increases infectiousness.

Panel 1 showing potential impacts of halting ART treatment programs

This is a major global problem. Pathogens can spread through migration and travel. A major HIV resurgence in Africa, home to two-thirds of people living with HIV, threatens to stall global progress toward the world’s goal of ending AIDS by 2030. A collapse of HIV treatment programs could also foster resistant HIV strains that jeopardize the efficacy of current regimens and divert resources from other AMR containment efforts. The cost of inaction is too high. If cuts persist, millions more lives could be lost, treatment interruptions could accelerate drug resistance, and the ripple effects will be felt worldwide. The world must act without hesitation.

A multi-faceted approach involving both immediate interventions and sustainable long-term strategies is required. Governments, global donors, and agencies like UNAIDS should implement emergency bridge funding to keep patients on ART through temporary drug procurement and boost generic drug supplies using the appropriate legal frameworks. Strengthening community networks is also critical. Community health workers and peer support groups can help locate patients who have dropped out of care and facilitate drug delivery or referral. Regional bodies and neighboring countries must also collaborate to ensure cross-border continuity of HIV care in affected health systems.

Simultaneously, a gradual transition toward domestic financing through expanded tax-based health insurance schemes and innovative financing approaches like social impact bonds could build resilience against future funding fluctuations. Community-based adherence support programs that empower patients with self-management skills and medication literacy should be expanded, alongside the implementation of differentiated service delivery models that can adapt to resource constraints. In addition, strengthening pharmacovigilance and resistance monitoring systems is essential, with particular emphasis on genotypic resistance testing capabilities in vulnerable regions.

Healthcare systems should prioritize the development of contingency supply chain management systems with buffer stocks of essential medications maintained at multiple levels of the distribution network. For instance, international cooperation mechanisms should be formalized to provide emergency pharmaceutical access during aid transition, while policy frameworks requiring longer notice periods and phased withdrawal of foreign aid for health programs could mitigate the most damaging effects of abrupt cuts. Meanwhile, global health leaders must integrate this crisis into broader AMR action plans by equitably sharing surveillance data, enhancing HIV drug resistance monitoring, and accelerating access to high-barrier ARVs like dolutegravir-based regimens.

The convergence of foreign aid volatility, treatment interruptions, and growing antimicrobial resistance represents a critical global health threat extending beyond HIV. By implementing these recommendations through coordinated action between donor nations, recipient countries, and multilateral organizations, we can safeguard decades of progress.

Authors’ Bio

Professor Sharifah Sekalala is Professor of Global Health Law at the School of Law, University of Warwick. An interdisciplinary researcher, her work sits at the intersection of international law, public policy, and global health, with a focus on global health crises and the role of law in addressing inequality, often through a human rights lens. She is a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences and currently leads a Wellcome-funded interdisciplinary project examining health apps in Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2024, she won the Feminist Legal Prize with Ania Zbyszewska for work that reimagines pandemic supply chains through feminist approaches that centre care as fundamental to the future of global health law. She is currently funded by Wellcome on After the End: Lived Experiences and Aftermaths of Diseases, Disasters, and Drugs in Global Health where she leads the work on law and reparations.

Shajoe J. Lake is a PhD candidate at the University of Warwick, funded by an ESRC scholarship, where he researches the intersections of critical political economy, One Health, aesthetics, and global health law. He works as a research assistant at the Centre for Global Health Law on two Wellcome Trust-funded projects: After the End: Lived Experiences and Aftermaths of Diseases, Disasters, and Drugs in Global Health and There Is No App for This! Regulating the Migration of Health Data in Africa. Previously, he was an international legal adviser at the Global Strategy Lab, advising stakeholders on legal responses to antimicrobial resistance, and a research fellow at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, where he led and supported academic, technical, and capacity-building programs in the Caribbean.

Stephen Okoboi is an Epidemiologist and Deputy Head of Research, Senior Research Administrator, and an Epidemiologist at the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI). He holds the prestigious NIH K43 Emerging Global Leader Award (2023–2028) and is currently pursuing an MSc in Health Economics at the University of York through the Thanzi Programme Studentship (2023–2026).

Dr Monica Kuteesa is a clinical epidemiologist with over 16 years of experience in HIV prevention and non-communicable diseases. She is currently based at the Uganda Virus Research Institute. Monica previously served as Director of Epidemiology at IAVI, where she was a strategic leader for HIV vaccine and antibody preparedness research including clinical development programs for infants, adolescent girls, and young women in East and Southern Africa. Monica holds a PhD in Epidemiology and Population Health from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, a Master’s in Global Health from the University of Sydney, and a Bachelor’s in Human Medicine and Surgery from Mbarara University of Science and Technology.

Elie Aaraj is the Founder and Former Director of the Association Soins Infirmiers et Développement Communautaire (SIDC), established in 1987. He holds a Maîtrise in Community Health from St. Joseph University and a BS in Nursing from the Lebanese University. Elie served as Director of the Nurse-Aid Technical School at Hayek Hospital and is the Founding President of the Order of Nurses in Lebanon. He co-founded and currently directs the Middle East and North Africa Harm Reduction Association (MENAHRA). He has led extensive research on HIV, drug use, and harm reduction, and is a Global Fund DCNGO Board member and an advisor at Sagesse University. His awards include the National Rolleston Award (2011), the “Kim Mo IM” Award (2019), and the “Medaille Marcelle Hochar” Award (2005).