Methodist Motives: The Ghost Story as Religious Propaganda

Written by Luke Holloway

The Methodist Movement

The history of ghost beliefs intersects with the realm of religion. In the mid-eighteenth century, the Methodist movement was spearheaded by John Wesley, an Anglican priest. His theology derived from Arminianism, which maintained that Christians could achieve salvation through individual piety.1 According to Wesley, this idea of ‘sanctification’ meant ‘being endued with those virtues, which were also in Christ Jesus’.2

Yet, Methodism caused controversy in the Church of England. ‘Sanctification’ challenged the premise of ‘predestination’, the belief that only God could determine the afterlife of a soul. Anglican critics even likened Methodist theology to Roman Catholicism. This called their other teachings into question too, such as itinerant preaching and emphases on spirituality. While the movement split following Wesley’s death in 1791, its membership continued to flourish in the later Georgian period, from 25,000 in 1770 to 286,000 in 1830.3

Methodism and Spirituality

Wesley refused to entertain most ‘superstitious’ customs. He did insist, however, that the Church should tolerate – or even incorporate – the spiritual beliefs that lay behind such practices. Methodist texts thus endeavoured to reconcile Anglican theology with witchcraft, miracles, and apparitions.4 In fact, Methodism stemmed from a divine encounter in 1738, when Wesley claimed to have sensed the Holy Spirit within him.5

This spirituality could then be used to regulate ‘superstitions’ by assimilating them into the Church’s theological framework. One example of this is spiritual possession. In addition to divine revelations, Wesley believed that diabolical powers could also take over the body and the soul. The solution was not necessarily medical treatment, but a renewal of religious devotion.6 Methodists then disseminated such teachings through print, due to the appeal of pamphlets and sermons.7

According to Sasha Handley, Wesley sought ‘a carefully-constructed balancing act between the tangible and mystical’, in which ‘superstition’ could legitimise the tenets of Anglicanism. The belief in ghosts typifies this. Enlightenment thinkers had challenged the basis of Christianity by emphasising the importance of empirical evidence. Yet, the reports of ghost sightings added a (supposedly) fact-based justification for religious belief. At the same time, the accounts were also a bulwark against Catholicism, as they ‘proved’ that Wesley’s teachings were the true path to God.8

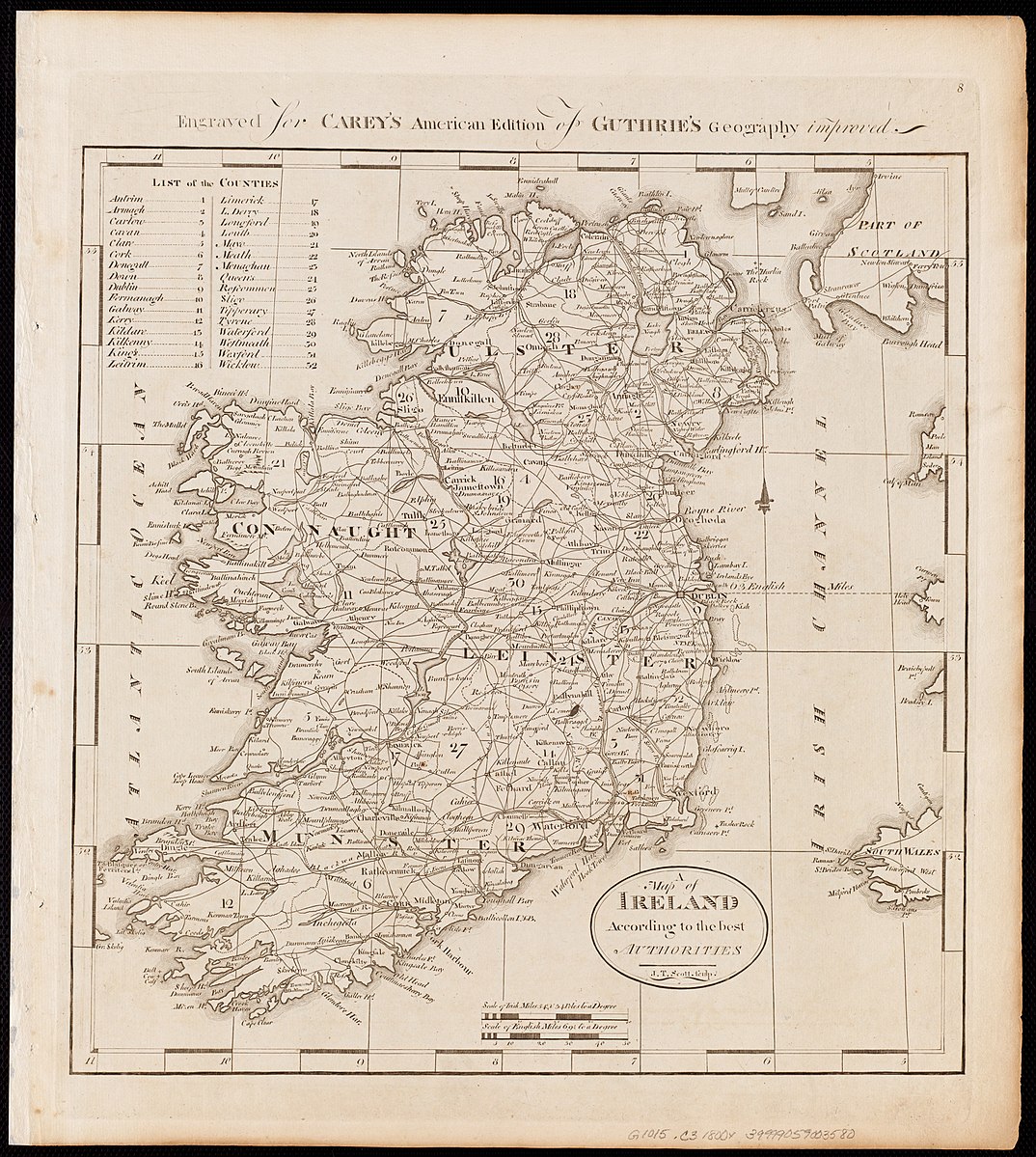

Methodism in Ireland

Ireland is an informative case for the spread of Methodism, as its preachers established charity foundations, local factions, and media networks. It was ultimately most successful in the southern settlements, especially those with weaker denominational ties.9 In particular, Wesley extended his spiritualist approach to Ireland. When he first visited in 1747, for instance, Wesley encountered a man who:

was under the full power of the devil… he wandered up and down in exquisite torture for just eighteen months: and then in a moment the pressure was removed: he believed God had not forsaken him… He resumed his employ, and followed it in the fear of God.10

After Wesley’s death, evangelists continued to spread his teachings in Ireland – the movement had 19,292 adherents there by the nineteenth century.11

Methodism and the Manuscript

The manuscript offers an important insight into the Methodist movement in Cork, Ireland. The city’s Protestant and Catholic factions had largely coexisted by the 1730s, yet the arrival of Wesleyan missionaries in 1748 was followed by anti-Methodist riots. These tensions remained in May 1750, when John Wesley visited Cork for the first time.12

The city’s Methodist Society built its preaching-house in 1752.13 This is possibly ‘the Preaching House’ named in the manuscript, which Cadwallader Acteson allegedly attended in 1788. Cadwallader meets James Rogers, an itinerant preacher, whose kindness gives him ‘revived hopes’. The source even appears to have strengthened the Methodist movement in Cork. Though other denominations ‘are not pleased’, the story ‘made much noise’ and, as a result, more locals are rumoured to have visited the preaching-house.

The manuscript outlines other aspects of Methodism too. The movement’s ‘class meetings’ attracted audiences of both men and women, and Irish Methodism especially appealed to the latter.14 It is thus unsurprising that Mary Acteson, Cadwallader’s husband, visits her local class to nurture ‘the experimental knowledge of [God’s] love’. 15 In fact, Elizabeth Ritchie, the collector of the manuscript, was a ‘class-leader’ herself at the time.16 The source also alludes to ‘heart religion’, which describes the Methodists’ emotional manner of dealing with the divine. Similarly, it emphasises the importance of individual prayer, as Cadwallader devoted himself to the Bible and thus achieved ‘such inward peace’.17

In this sense, the manuscript not only references the Methodist Society in Cork, but actively sought to spread its evangelical teachings.

Endnotes

- John Fulton, ‘Clerics, Conjurors and Courtrooms: Witchcraft, Magic and Religion in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Ireland’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Ulster University, 2016), p. 175.

- John Wesley, Sermons on Several Occasions, Volume 1 (New York: G. Lane & C. B. Tippett, 1845), p. 148. Google ebook.

- Owen Davies, ‘Methodism, the Clergy, and the Popular Belief in Witchcraft and Magic’, History, 82.266 (December 2002), 252-65 (p. 259).

- Ibid., pp. 263, 264.

- Sasha Handley, Visions of an Unseen World: Ghost Beliefs and Ghost Stories in Eighteenth-Century England (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), p. 143. Taylor & Francis ebook.

- Fulton, ‘Clerics, Conjurors and Courtrooms’, pp. 190, 187.

- Handley, Visions of an Unseen World, pp. 162, 164.

- Ibid., pp. 161, 157, 158.

- David Hempton, ‘Methodism in Irish Society, 1770-1830’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 36 (1986), 117-42 (pp. 123, 125).

- John Wesley, The Works of the Rev. John Wesley, The Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh Numbers of his Journal (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1827), p. 174. Google ebook.

- Fulton, ‘Clerics, Conjurors and Courtrooms’, p. 181.

- Simon Lewis, ‘Five Pounds for a Swadler’s Head’: The Cork Anti-Methodist Riots of 1749-50’, Historical Research, 94.263 (February 2021), 51-72 (pp. 55, 58, 66).

- Ibid., p. 68.

- Fulton, ‘Clerics, Conjurors and Courtrooms’, p. 185.

- [Hester Ann Rogers?] to Elizabeth Ritchie, c. 1788, Manchester Methodist Archives, MAM/FL/33/4.

- E. Dorothy Graham, ‘Ritchie [Married Name Mortimer], Elizabeth (1754-1835), Biographer.’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004 <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/63471> [accessed 23 February 2021].

- [Hester Ann Rogers?] to Elizabeth Ritchie, c. 1788, Manchester Methodist Archives, MAM/FL/33/4.

Primary Sources:

[Hester Ann Rogers?] to Elizabeth Ritchie, c. 1788, Manchester Methodist Archives, MAM/FL/33/4.

Wesley, John, Sermons on Several Occasions, Volume 1 (New York: G. Lane & C. B. Tippett, 1845). Google ebook

–––– The Works of the Rev. John Wesley, The Sixth, Seventh, Eighth, Ninth, Tenth, and Eleventh Numbers of his Journal (New York: J. & J. Harper, 1827). Google ebook

Secondary Sources:

Anderson, Misty G., Imagining Methodism in Eighteenth-Century Britain: Enthusiasm, Belief, & the Borders of the Self (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012). ProQuest ebook

Davies, Owen, ‘Methodism, the Clergy, and the Popular Belief in Witchcraft and Magic’, History, 82.266 (December 2002), 252-65

–––– ‘Wesley’s Invisible World: Witchcraft and the Temperature of Preternatural Belief’, in Perfecting Perfection: Essays in Honour of Henry D. Rack, ed. by Robert Webster (Cambridge: The Lutterworth Press, 2015), pp. 147-72

Fulton, John, ‘Clerics, Conjurors and Courtrooms: Witchcraft, Magic and Religion in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Ireland’ (unpublished doctoral thesis, Ulster University, 2016)

Graham, E. Dorothy, ‘Ritchie [Married Name Mortimer], Elizabeth (1754-1835), Biographer.’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 23 September 2004 <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/63471> [accessed 23 February 2021]

Handley, Sasha, Visions of an Unseen World: Ghost Beliefs and Ghost Stories in Eighteenth-Century England (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016). Taylor & Francis ebook

Hempton, David, ‘Methodism in Irish Society, 1770-1830’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 36 (1986), 117-42

Lewis, Simon, ‘Five Pounds for a Swadler’s Head’: The Cork Anti-Methodist Riots of 1749-50’, Historical Research, 94.263 (February 2021), 51-72

E-Resources:

‘Inner Lives: Emotions, Identity, and the Supernatural, 1300-1900’, at https://innerlives.org/

‘John Wesley and Methodism’, In Our Time, BBC Radio 4, 10 December 2020

Images:

'A map of Ireland according to the best authorities (3045238263)', <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:A_map_of_Ireland_according_to_the_best_authorities_(3045238263).jpg> [accessed 7 June 2021].

'Portrait of John Wesley Wellcome L0003565', <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_John_Wesley_Wellcome_L0003565.jpg> [accessed 7 June 2021].

Click to hear the 'Print & Religion' episode of our podcast.

Portrait of John Wesley, an Anglican priest and the leader of Methodism.

Map of Ireland (c. 1800).