What is a Design Study and how do you create one?

A design study is an exploration of a design

If we want to change the world for the better we first have to accurately describe how it is now, how people live in it, and how the design of things has positive and negative impacts. The detail matters. We need to describe the salient features that matter, as efficiently as possible. And then we can envision how it might be different, with a convincing grasp of the salient details. All of this needs to be done in an efficient, engaging, and compelling way. That is a design study.

It considers the intentions of the designer (design-as-intended), how the design has been implemented and changed in implementation (design-as-implemented), and how it is experienced by the people who interact with it and use it (design-as-experienced). Design studies present an analysis of a design or designs.

They should also consider the gap between intention, implementation, and experience. Does it do what the designer thinks it will do? And do people experience it in the expected ways? If not, what are the consequences of that gap?

This is a critical evaluation. The researcher evaluates the design. How well does it:

- Fit with the needs, goals, virtues, cultures, and capabilities of the people who use it?

- Stick in use for a length of time that justifies the cost to design, implement, adopt and maintain?

- Spread to other people, context and uses, amplifying its value?

- Grow a capability for further enhancements and innovations?

This is called the "fit, stick, spread, and grow" framework for evaluating designs (O'Toole, 2015). It is a "transdisciplinary" approach, in that when answering these questions we move through many different disciplines. For example, understanding cultural aspects may draw upon history, sociology, and linguistics. There are engineering and manufacturing aspects to designs, and we may need to know about material science aspects. There are always economic issues. And to understand the match or mismatch between intention and experience, psychology is useful. But we only need to visit each of these disciplines as deeply as necessary to inform out study. We need to pick out the "salient features and issues". Typically, design studies are developed iteratively, going into progressively more depth as needed. They are usually done by interdisciplinary teams.

Why do we do design studies?

Christopher Frayling (1993, following the ideas of Herbert Read) described three reasons for doing design research:

- Research for design – to give us insights from which we can develop new designs.

- Research into designing – reflectively researching our own design methods, informed by work with colleagues, and scholarly work from the design research community, to improve how we do designing.

- Research through design – learning about the world in which, and for which, we are designing.

In practice a design study is likely to generate knowledge for each of these goals, but most often our focus is on A, generating knowledge that can be applied to enhance existing designs or to create new designs.

A design study may also present a redesign or a new design

We start by understanding designs in action, as-implemented, and the impact they have on real people. We can identify design challenges in what we analyse and critically evaluate. Challenges may concern inefficiencies, ways in which the design doesn't achieve what it sets out to do. Or they may concern conflicts in the needs, wants, goals, capabilities of people (see the section on personas below for more on this). These are often the most interesting design challenges, and increasingly concern conflicts between the desires of people and the health of the planet.

A design study may then go on to describe a redesign, or a new design, informed by those insights. In this way, design studies are creative as well as analytical and critical. We can apply the same methods, ask the same questions, about a proposed design. We can answer these questions, analysing and evaluating the proposed design, using evidence from user research, observations, scientific research, and prototyping. Design Thinking is an approach that encourages prototyping early and often. See Tom Kelley's article "Prototyping is the Shorthand of Design" (2001) for a description of how to do this. Another classic Design Thinking technique is to get a broad collaboration of experts involved in creating the design study - especially the end users. You need to get to the truth, to the authentic experience of the design in action. Get beyond the hype, get real.

How to develop a design study

A design study is an investigation into what is or what might be within a chosen frame.

For example, we may investigate in the frame "the experiences of vegans when using public transport in London" to consider how well the designs involved in that context fit for those people. Or we may have a smaller frame "the experiences of vegans accessing food at rush hour in London rail stations". We might also shift the frame during the investigation, perhaps we discover the real issues are with "opportunities and capabiliities for retail outlet managers to design inclusive menus in a highly competitive market". That could lead us to improve the lives of vegans in London. But it has a different focus. The role of framing and reframing in designing has been explored in depth by Kees Dorst in his book "Frame Innovation" (2015).

The output, the final presentation of the findings, should be clear, simple, and consise. In some cases it is written or pre-recorded, often with multimedia content. In other cases it is presented live to a panel.

It's often good to do this in the form of a user story, identifying what the user[s] care about and want to achieve, and the key points in their journey. What makes it work, what makes it fail, what they find annoying, what makes it awesome - and why.

But that story needs to be based on detail, produced through the investigation. It needs to be convincing. Think of the presentation as a pitch.

Some of the basic elements in the detail, that will help you in creating your study, are as follows. Use these techniques iteratively to generate increasing depth to your study. At points you will gain insights that you will want to follow up in more depth. For example, if you spot a conflict between people's goals, and can see that to be the source of the main problems, it's OK to go deep on that. You might discover what designers call "a generative idea" that helps you to find a great new solution. Run with it as far as you need to, but don't get too fixated. You can always return to other aspects later. If you are working in a team, you can delegate different parts of the investigation to team members, but keep communicating. Miro is a good place to record what you find as a team. But make sure you structure your board well so that the knowledge is usable.

Personas are a key part of the evidence base to develop. Try to represent the key people, including designers, users, people who interpret the design for others, people who have power over its implementation etc. Often designers will begin with a single category of person - the ones that are supposed to benefit from the design. This is a good way to keep control of the complexity of the investigation. But be aware that designs have impacts and depend on lots of different people. As you delve into the design, you will find more different people to learn about. Don't forget the people involved in making the design possible - for example, low-wage manufacturing workers in Cambodia. Personas give us background information about these people. We want to know all the salient features that impact upon their actions and experiences. Most importantly, identify what they want (or may want) to get out of the design, and what the virtues are that guide their intentions. By "virtue", we mean how they define good in their own actions and the world. So for example, "sustainable" and "fair for everyone" are virtues, as is "rich" and "pleasurable" - we don't have to agree with what people define as virtues, but we do have to know them.

Use these virtues and goals to thematically tag knowledge developed in the design study. For example, if you have a user called "Jane" who wants to achieve "calmer communications at work", you have a key theme: "Jane, calmer communications at work". And maybe there's also Jane's manager Jools, who wants to greater efficiency and speed - "Jools, greater efficiency and speed". You should keep a table listing all of these. Considering how they relate, conflict or converge, is an essential task in doing the design study. You might find that conflicts are the source of the main problems. You might then generate design challenges from identifying those conflicts, setting as the creative goal finding ways to alleviate the conflicts.

An interesting innovation in this approach is to create personas for non-human agents and systems. For example, if looking at food systems, consider orangutans in the jungle of Borneo and how they are impacted by the use of palm oil in your design. Or perhaps the jungle itself, as an ecosystem. You will definitely find conflicts between different people and these non-human entities. And in that you can identify some of the most important design challenges of our times.

System maps tell us about the ways in which people, resources (including knowledge), and processes (algorithms) are organised - either deliberately by design, or as emergent properties of actions and natural phenomena. They can get very complicated. Your task is to pick out the salient features and patterns. The tanglegram, as described by Carvalho and Yeoman (2019) is a good tool for this. Here's some examples from their article:

User journey maps take personas and show how the people represented interact with designs and systems, including the environment and other people, during a set time. Ellen Lupton's book Design is Storytelling (2017) is the best guide to creating these stories. Sometimes they are presented as a quest. The person is aiming to achieve some specific goals. Although this is not necessary. We may want to illustrate how they interact with things in a less goal-oriented manner. For example, if we are looking to reshape behaviour through nudges in a design.

User Interface, Information Design and Ergonomics analysis zooms into the detail of systems, looking at the aspects through which humans interact with designed things. Humans sit, stand, move within designs - ergonomics studies how designs are adapted to physical form, and how people adapt to form. We use buttons, slides, triggers, all kinds of interfaces to control systems - how well are they arranged and how well do the allow us to have control? And to do all of that, we need information guiding our actions, prompting us to make choices and think, and giving feedback on what we do. These aspects of designs include constraints on our actions, affordances (things we can do with them), and enabling constraints - as described by Don Norman in his classic book The Design of Everyday Things (originally 1998, now in an updated edition of 2013).

Empathy maps give life to the personas in relation to the design. An empathy map is a record of the experience of a person when they encounter a design. You might create empathy maps that present the overall experience of the person, or their experience at a critical point in their user journey. Typically an empath may records what the person experiences, feels, thinks, and does.

Bringing it all together

What happens next? That all depends on the context within which you are designing. What do you need to get out of it? But also, in every design project, maximise what we can learn about designing and the world.

Have you been commissioned to address a specific design challenge? In which case you need to present your pitch either as identifying design ideas that will address it, or arguing that the challenge needs to be reframed and investigated further. How does your design study contribute as research to improve a design? (Frayling's research type A, research for designing). Or have you done the design study more speculatively? Have you identified design challenges that need to be addressed?

Did you do the design study to learn more about desiging? Perhaps you have identified a gap between the intentions of the designer, the implementation and the experience. What does this, for example, tell us about the culture of designing (see Guy Julier's book The Culture of Design, 2013). In all design work we should reflect on this, and contribute to Frayling's research type B, research about designing.

And what did the exercise tell us about the world in which designs operate? What can we learn about people, systems, environments? This is an equally important outcome, and should always be in the minds of designers.

A really great design study brings all of these together into a compelling story, told with impact.

An example

For most people most of the time driving a car should be an efficient, pleasurable, relaxing, and most importantly safe experience. Car manufacturers have used advances in automotive and digital technologies in trying to achieve these goals. Two areas of development are key to this:

- controlling the environment within the vehicle (air con, heated seats, music, communications);

- improving the control loop:

- providing better information about the road, driving conditions, and the vehicle (rear view cameras, sensors, AI to detect speed limits, automatic transmission and engine controls, navigation aids);

- supporting planning and decision making, to lower the cognitive load on the driver and improve safety;

- enabling the swift execution of actions as required, without the driver taking their attention away from the road, or having to search for the correct control.

The design theorists John Seeley Brown and Mark Weiser defined design principles for achieving these goals, called "calm technology" - the idea that technology should be as simple as possible, unobtrusive, and visible in just the right ways at the right time. These principles have been applied well to software and web design (see Steve Krug's Don't Make Me Think, 2014). But how are car designers implementing these principles?

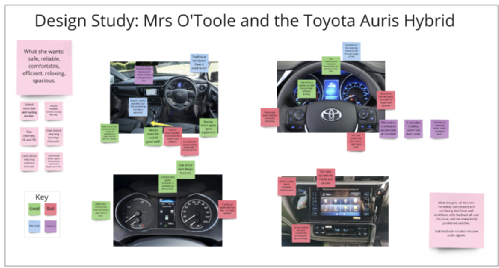

We explored the case of a 2018 Toyota Auris Excel hybrid (top of the range, many optional extras) owned by education executive and school teacher Emma O'Toole. We began by focussing on her needs. She is a busy professional, mostly driving between a group of schools in Coventry and Warwickshire to support teachers. The roads on these routes are congested and dangerous. This is stressful, and her day often starts before sunrise. She has had back pain with a previous car. She needs comfort, simplicity, reliability, and safety.

We looked at her car with her, taking photos and exploring the experience of driving it. Photos of the car's interface are given in the design board below, with annotations indicating good, bad, neutral, and dangerous features of the interface. This doesn't capture all of the details, as driving is a dynamic and complex process. However, we can see that there are many different features of different systems. The "workflows" for taking information, processing, deciding, and acting are spread across multiple confusing interfaces. There seems little rationale for this design. We suspect that the design has been badly adapted from simpler more traditional car designs, with new features being grafted in wherever space is available. It does not seem to have been designed as a coherent system from the user's perspective. This leads to cognitive overload and the potential for dangerous errors. There are some buttons that have been placed inappropriately. For example, the traction control button is between the two heated seat buttons, and is exactly the same shape. So when reaching down (a long way down) to change the heated seat setting, it is possible to accidentally switch off the traction control. This could lead to an accident. There are other similar design mistakes.

In conclusion, we can see how not taking a systematic and user-focussed approach, considering the workflows and cognitive loads, can result in designs that are difficult to use, and in this case, potentially dangerous. Car designers should follow the principles of calm technology, start from the needs of the user in the dynamic environment of driving, and create interfaces and workflows for simplicity and safety.

Click to enlarge: